Info

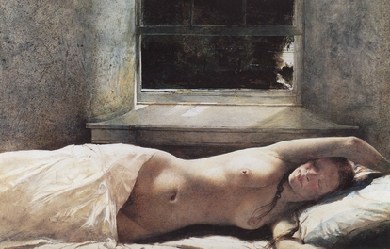

A portrait of a fairy

Sophie Gengembre Anderson

Unknown

Private Collection

Alice Guerin Crist (1876–1941) was an Australian poet, author and journalist born in Clare Castle, Ireland on 6 February 1876 to Patrick and Winifred (née Rohan or Rouhan) Guerin. When she was two years old, the family migrated to Queensland, where her father taught in rural schools, including as head teacher of Tent Hill Upper school in May 1880.

I was Discovered in the basement of "Jeff Davis Hospital" nearly dead from over stuffing my frame with "Rat Milk" rescued by two "Scottish Strippers" whom earned there living at "Natchez Under the Hill" Both parents, Tried to teach me as I grew older to escape any Mental obstacle, I never paid attention, I just kept craving "Beutiful Breast Milk" that stared at me each morning as I laid hopelessly in the middle of my mother and mother, with a "Old Clothe Diaper" constructed from Dollar bills that were stuffed in the "Oversized Bra's" of both of my parents the "Night before" Just kidding, Everything's true, Except for the two female parents, the "Money Constructed Diaper" and the "Rats Milk"........ It was a "Cat" My goal is to truly "Capture the Art of Writing" I'm not the Best, And I'll never Claim to be! I just want to join and mingle, With my "Fellow Poets" Dream, Write, And always Remember, That Your "Right" and I'm "Left" Handed

Gabino-Alejandro Carriedo (Palencia, 1923 - San Sebastián de los Reyes, 1981) fue un escritor palentino cuya obra se encuentra íntegramente contenida en el siglo XX. Cultivó especialmente el género poético, presentando muchos de sus libros en revistas de la época y siendo editor de algunas de ellas Nació en el año 1923 en Palencia; a partir de la década de 1940 comienza su carrera literaria. Su andadura se inició en su ciudad natal, donde creó, junto a José María Fernández Nieto y otros, la revista Nubis (1946) y publicó un libro vinculado al Tremendismo, Poema de la condenación de Castilla. Posteriormente se trasladó a Madrid, donde escribió obras como La piña sespera, vinculándose al Postismo de Carlos Edmundo de Ory y Eduardo Chicharro Briones y participando activamente en esta vanguardia. En los años 50 crea, junto a Ángel Crespo, el Realismo mágico en poesía, que difundirán a través de revistas como El Pájaro de Paja y Deucalión. A partir de 1960 su poesía torna hacia temas sociales con poemarios como El corazón en un puño o Política agraria. En la década siguiente su obra dará un nuevo giro hacia la vanguardia, con Los lados del cubo, libro influenciado por el Modernismo brasileño y el Constructivismo. Falleció repentinamente el 6 de septiembre de 1981 en San Sebastián de los Reyes, fue incinerado en Madrid y sus cenizas fueron llevadas al cementerio de Ntra. Sra. de los Ángeles de Palencia. Obra * Poema de la condenación de Castilla. Palencia: Merino. 1946 * El cerco de la vida(1946-47), aunque editado póstumamente en Segovia: Pavesas. 2002 * La sal de Dios (1948). Inédito hasta su inclusión en Poesía. 2006 * La piña sespera (1948). Inédito hasta su inclusión en Nuevo compuesto descompuesto viejo. 1980 * La flor del humo (1949). Inédito hasta su inclusión en Nuevo compuesto descompuesto viejo. 1980 * Los animales vivos (1951), aunque publicado en Carboneras de Guadazón: El toro de barro. 1966 * Del mal, el menos. Madrid: El Pájaro de Paja. 1952 * Las alas cortadas. Madrid: La piedra que habla. 1959 * El corazón en un puño. Santander: La isla de los ratones. 1961 * Política agraria. Madrid: Poesía de España. 1963 * Los lados del cubo. Madrid: Poesía de España. 1973 * Nuevo compuesto descompuesto viejo. Madrid: Hiperión. 1980 * Lembranças e deslembranças (años 70), aunque editado póstumamente en Cáceres: El Brocense. 1988 * El libro de las premoniciones (póstumo). Cuenca: El toro de barro. 1999 * Poesía interrumpida (antología). Madrid: Huerga & Fierro. 2006 * Poesía (obra completa). Valladolid: Fundación Jorge Guillén. 2006 * Sonetos. Palencia: Fundación Díaz Caneja. 2010. Introducción y selección de Mario Paz González. Referencias http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabino-Alejandro_Carriedo

Books @ amazon.com/author/sashalogan More content at Allpoetry.com/sashalogan Writing random thought. Born Downriver, 11 miles south of Detroit. Moved to Cleveland area at age 14. Worked as a baker and in the steel/metal industry. Crime in America is high. Rent in America is high. You get what you pay for. I'm living in Michigan now. The less you have, the less you have to deal with. ✌️ and ❤️

.jpg)

¡La obra poética de Castillo es una sinfonía! “Nada que sea humano le es ajeno” Horacio Castillo (Ensenada, Provincia de Buenos Aires 1934 – La Plata 5 de julio de 2010 ) fue un poeta, ensayista y traductor argentino. Fue también miembro de número de la Academia Argentina de Letras y correspondiente de la Real Academia Española. Realizó diversas traducciones del griego. Se recibió de abogado en la Universidad de La Plata. Obra Su obra fue traducida a varios idiomas, como el francés, inglés, portugués e italiano. * Descripción (1971, poesía) * Materia acre (1974, poesía) * Tuerto rey (1982, poesía) * Alaska (1993, poesía) * Los gatos de la Acrópolis (1998, poesía) * Cendra (2000, poesía) * Música de la víctima y otros poemas (2003, poesía) * Mandala (2005, poesía) * La casa del ahorcado (reúne su obra poética de 1974-1999) y Por un poco más de luz (reúne su obra poética de 1974-2005). Premios y reconocimientos * 1988 - Primer Premio Fondo Nacional de las Artes por traducción literaria * 1993 - Premio Konex, Diploma al Mérito * 2001 - Ciudadano ilustre de La Plata Referencias Poemas Corazón – poemascorazon.com/poesia/poemas-de-horacio-castillo.html Wikipedia – http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horacio_Castillo

El Poeta CamposZamb, cuyo nombre de pila es Ever Harley Campos Zambrana, nació el domingo 13 de abril de 1975, en Jinotepe, Carazo, Nicaragua, es el mayor y único varón de tres hermanos. Su inquietud por el idioma, por las letras, la experimentó desde sus tiempos de escolar, pero empezó a ensayar Poesía desde su adolescencia, sin embargo, pronto suspendió su creación literaria, por el estereotipo de que ser Poeta, o Escritor, no permite ganarse la vida, por ser muy impráctico, hasta el punto de la creencia, o superstición, de que tales artistas terminan dementes. CamposZamb, se limitó a sus estudios formales, todos en su lugar de nacimiento. En 1992, se graduó de Maestro de Educación Primaria, en la Escuela Normal Ricardo Morales Avilés. En 1993, obtuvo el Bachillerato, en el Instituto antes nominado Alejandro García Vado, hoy Manuel Hernández Martínez, y en 1999, obtuvo la Licenciatura en Derecho. En el 2001 y en el 2003, respectivamente, fue autorizado por la Corte Suprema de Justicia, para ejercer la Abogacía y el Notariado, Profesiones a las que se ha dedicado al día de hoy. https://www.facebook.com/abogado.camposzambrana A sus 18 años de edad, ya había escrito Rubén Darío (Martes 13 de abril de 1993), Poema para el que estudió la Obra del padre del modernismo, profundizó su análisis de la Autobiografía, y se aprendió de memoria un Diccionario Enciclopédico, al que le dedicó su Poema A mi amigo, el Diccionario (31-5-2014). El léxico del Poema Rubén Darío, aconseja acompañar su lectura con un Diccionario competitivo. El miércoles 27 de agosto de 2014, mejoró su lectura, y su versificación, pasó de 69 a 71 versos. A sus 21 años de edad, CamposZamb, ya había escrito Homenaje a la indiferencia (Abril de 1996), que originalmente tituló Hacia bienandanza, y lo hizo de 420 versos. Poema que se distingue por su exuberancia de ideas, y por su fluido neologismo, una de las principales características de su creador. El Poema ha permanecido totalmente inédito durante 18 años, y en agosto de 2014, su Autor, a sus 39 años de edad, lo renovó, y lo amplió a más de 600 versos, cerca de 200 versos en menos de un mes, mientras trabajaba en más de 10 nuevos Poemas, y ejercía la Abogacía y el Notariado. Es el Poema más extenso que ha escrito por ahora. Desde 1993, hasta antes de octubre de 2012, en que creó su perfil de Facebook, CamposZamb pasó en el anonimato, y aún no había vuelto a escribir, excepto que como Abogado, cuenta aparte lo que ha redactado como Notario, en más de 17 años de experiencia, desde sus inicios como Pasante en septiembre de 1997, ha cultivado la prosa, con la elaboración de más de 10,000 Escritos, en su mayoría de varias páginas, con los que ha destacado por su pensamiento y por su expresión, y aun por su innovación creando formatos nuevos, distribuidos en más del 40 % del Foro de su País, sin omitir los cientos de documentos, como cartas, currículums, monografías, incluso alegatos y escrituras públicas, etcétera, que ha confeccionado para terceros. Ha sido a partir de mayo de 2014, que CamposZamb, ha continuado su vocación literaria. Creó la página de Facebook Poemas CamposZamb (https://www.facebook.com/pages/Poemas-CamposZamb/1439033256351445), el primer sitio web en el que publica sus Poemas, y los reproduce en más de 10 páginas de la internet, lo que se comprueba con la etiqueta CamposZamb, o Poeta CamposZamb . Entre el 25 de abril y el 2 de mayo de 2014, CamposZamb escribió el Poema LA PALABRA DE DIOS, el que desde su publicación, el miércoles 7 de mayo de 2014, en www.lajicara.net, hasta la fecha, domingo 14 de septiembre de 2014, sin ningún plan publicitario profesional, ni masivo, ha alcanzado por ahora, 9,968 visitas, siendo el blog más visitado en esa página (http://www.lajicara.net/tercer-concurso-de-poesia-libre-2014/la-palabra-de-dios), ocupando en la misma el tercer lugar en visitas el Poema Rubén Darío, con 1,959 (http://lajicara.net/tercer-concurso-de-poesia-libre-2014/ruben-dario), mismo cuya publicación ya ha sido aprobada para el N° 14 de la Revista digital mexicana FACTUM. El Poema LA PALABRA DE DIOS, ha sido publicado en la Revista FACTUM, N° 13, páginas 84 y 85. A excepción de los más de 10 nuevos Poemas en los que está trabajando, por ahora, CamposZamb, oficialmente ha escrito 1,075 versos, constituidos por los Poemas: LA PALABRA DE DIOS (50), Gracias Madre (79), Rubén Darío (71), A mi amigo, el Diccionario (152), Ámame (39), Ideal (29), A nuestros estimados Poetas bohemios (24), La trascendencia de los instantes (10), A Caupolicán (12), Homenaje a la indiferencia (609). El Poema La trascendencia de los instantes, escrito entre el 19 y el 20 de julio de 2014, ha sido seleccionado para formar parte de la Antología Versos en el aire III, como resultado del Tercer Concurso de Poesía Versos en el aire, promovido por Diversidad Literaria, colectivo y portal literario español. http://www.diversidadliteraria.com/resultados-concursos/versos-en-el-aire-iii/ CamposZamb ha recibido comentarios de autores de más de 10 Países: México, España, Venezuela, Colombia, Argentina, Brasil, Perú, Guatemala, Costa Rica, San Salvador, Estados Unidos, Italia, Nicaragua, Honduras… Dos de las páginas en las que ha recibido más comentarios, son www.poematrix.com, y www.lajicara.net.

William Collins (25 December 1721– 12 June 1759) was an English poet. Second in influence only to Thomas Gray, he was an important poet of the middle decades of the 18th century. His lyrical odes mark a turn away from the Augustan poetry of Alexander Pope’s generation and towards the Romantic era which would soon follow. Biography Born in Chichester, Sussex, the son of a hatmaker and former mayor of the town, he was educated at The Prebendal School, Winchester and Magdalen College, Oxford. While still at the university, he published the Persian Eclogues (1742) which he had begun at school. After graduating in 1743 he was undecided about his future. Failing to obtain a university fellowship, being judged by a military uncle as 'too indolent even for the army’, and having rejected the idea of becoming a clergyman, he settled for a literary career and was supported in London by a small allowance from his cousin, George Payne. There he was befriended by James Thomson and Dr Johnson as well as the actors David Garrick and Samuel Foote. In 1747 he published his collection of Odes on Several Descriptive and Allegorical Subjects on which his subsequent reputation was to rest. The poems are characterized by strong emotional descriptions and the personal relationship to the subject allowed by the ode form. At the time little notice was taken of these poems, which were at odds with the Augustan spirit of the age. With the depression on his lack of success, aggravated by drunkenness, he sank into insanity and in 1754 was confined to McDonald’s Madhouse in Chelsea. From there he moved to the care of a married elder sister in Chichester until his death in 1759, when he was buried in St Andrew’s Church. After the Odes, although he had many projects in his head, none came to fruition. His only other poems were the ode written on Thomson’s death (1749) and the posthumously discovered and unfinished “Ode on the popular superstitions of the Highlands of Scotland”. An intriguing addition, now lost, is the “Ode on the Music of the Grecian Theatre” that he described and proposed sending to the musician William Hayes in 1750. Hayes had just set “The Passions” by Collins to music as an oratorio that was received with some acclaim. This, coupled with the popularity of the Persian Eclogues, a revised version of which was published the year he died, was the closest approach to success that Collins knew. Legacy Following his death, his poems were issued in a collected edition by John Langhorne (1765) and slowly gained more recognition, although never without criticism. While Dr Johnson wrote a sympathetic account of his former friend in Lives of the Poets (1781), he dismissed the poetry as contrived and poorly executed. Charles Dickens was dismissive for other reasons in his novel Great Expectations. There Pip describes his youthful admiration for a recitation of Collins’s The Passions and comments ruefully, 'I particularly venerated Mr. Wopsle as Revenge throwing his blood-stain’d Sword in Thunder down, and taking the War-denouncing Trumpet with a withering Look. It was not with me then, as it was in later life, when I fell into the society of the Passions and compared them with Collins and Wopsle, rather to the disadvantage of both gentlemen’. Works * Persian Eclogues (1742); these were revised as Oriental Eclogues in 1759. * Verses humbly address’d to Sir Thomas Hanmer on his edition of Shakespeare’s works (1743); republished in a revised edition in 1744, in which “A Song from Shakespeare’s Cymbeline” was included. * Odes on Several Descriptive and Allegorical Subjects (1746) * Ode on the Death of Thomson (1749) * Ode on the Popular Superstitions of the Highlands (written 1750, unpublished until later editions) Editions * Poetical works of William Collins, ed. John Langhorne, originally published in 1765; several editions followed, to which Dr Johnson’s life of Collins was added. * A scholarly edition was published in The Poetical Works of Gray and Collins (ed. Austin Poole) by Oxford University Press in 1926; from the same press there followed the definitive edition of The Works of William Collins (ed. Wendorf & Ryskamp) in 1979. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Collins_(poet)

Carmen Conde Abellán (Cartagena, 15 de agosto de 1907 - Madrid, 8 de enero de 1996) fue una poeta, narradora e intelectual española. En 1931 fundó, junto con Antonio Oliver Belmás, la primera Universidad Popular de Cartagena. Fue la primera académica de número de la Real Academia Española; pronunció su discurso de entrada en 1979.

Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (23 September 1861– 25 August 1907) was a British novelist and poet who also wrote essays and reviews. She taught at the London Working Women’s College for twelve years from 1895 to 1907. She wrote poetry under the pseudonym Anodos, taken from George MacDonald; other influences on her were Richard Watson Dixon and Christina Rossetti. Robert Bridges, the Poet Laureate, described her poems as ‘wonderously beautiful… but mystical rather and enigmatic’. She published five novels, the best known of those being The King with Two Faces.

Onelio Jorge Cardoso (Calabazar de Sagua, Cuba, 14 de mayo de 1914 - La Habana, 29 de mayo de 1986) fue un autor cubano. Conocido como "El cuentero mayor", se le considera el Cuentista Nacional Cubano. La mayoría de sus obras han sido adaptadas para el cine, el teatro, la televisión e incluso la radio. Cursó estudios hasta el nivel de Bachillerato, cuando tuvo que dejar por problemas económicos en su familia, teniendo que desempeñar diversos oficios para apoyar a su familia. Uno de estos empleos fue el de viajante de comercio que le permitió conocer diferentes lugares y a diversos personajes populares, que le sirvieron de modelos para los personajes de sus obras. En 1945 publica en México su primer libro, Taita, diga usted cómo y aparecen dos cuentos en Cuentos cubanos contemporáneos y en Cuentos Cubanos.

Luis Florencio Chamizo Trigueros (Guareña, Badajoz, 7 de noviembre de 1894–Madrid, 24 de diciembre de 1945) fue un escritor y poeta español. Nació en el seno de una familia humilde y trabajadora de Extremadura. Recibió enseñanza primaria en Guareña y se trasladó a Madrid para empezar a cursar Bachillerato, que finalizó en Sevilla, donde también obtuvo el título de perito mercantil. A los 24 años se licenció en Derecho en la Universidad de Murcia, donde terminó los estudios empezados en la Universidad Central de Madrid.

Giovanna Chadid (Bogotá, 6 de Diciembre de 1985) Escritora y Poetisa Colombiana. Estudio Literatura y Filosofía. Ha publicado artículos sobre arte, literatura y política en medios como: www.superdemokraticos.com/verseuchende-politik/ Alemania – Revista Alejandría/México – Revista Enter/Buenos Aires - Revista Plant/Canadá Revista Independiente El Cartel/Bogotá – La conjura de los necios/suplemento literario revista Avatares/Pasto- Nariño. Ganadora de la beca Colcultura 2009 Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Nuevas Herramientas Para la Creación) Beca 2010 Casa de Poesía Silva (Creación literaria) Su primer libro es Guevonaditas Varias (Corpos Editora/Portugal 2011) traducciones al español/portugués http://www.worldartfriends.com /store/1221-giovanna-chadid-guevonaditas-varias.html Maneja la bitácora: www.literaturachadid.blogspot.com Actualmente se encuentran en proceso una novela que será publicada en 2013 * Con un léxico renovado y autentico, opta por una poesía dedicada al amor, la autocompasión, la crítica social, hasta el humor efervescente y provocador, resalta con ironía la cotidianidad y deja al margen de su obra a la sociedad burgués contemporánea, sin pensar en hacer amigos o enemigos, No le importa. La intensidad de su vida está llena de contrastes que pasan de un abierto ateísmo a un intimismo espiritual y de un espíritu crítico de la sociedad, expresado en su obra poética y en sus ensayos. Sus relatos contemporáneos y de interés colectivo, son tratados con desenfado, humor e ironía, mediante un lenguaje popular, sus escritos divierten a muchos, escandalizan a algunos, pero ante todo, no dejan a nadie indiferente. "La prosa de Giovanna es un delirio de exuberancia, maestría, una gamberrada deliciosa, se ríe de todo, y al mismo tiempo, es muy fiel y respetuosa a una tradición importante (no sólo filosófica, sino también literaria) que ha leído con atención y perspicacia. Es fresca, es inteligentísima, es veloz y sorprendente. Es pura subversión, puro humor lacerante, y también es tierna" Gabriel Ospina * En su poesía, en su escritura hay una cruza, en un sentido casi genético, de memorias literarias bastante extraordinarias, siempre en la condensación mínima, en la cesura, la elipsis, la interrupción conjuradora de los tiempos por venir, que no son más que la experiencia de esas memorias. Justo ahí su poesía se lee como la respuesta, la voz de aquel a quien se dirige el poema. Voces, con ella y con ellas, por ellas y a través de ellas, vamos, desde siempre y hasta siempre. Y alguna vez, quizás sólo una vez, cada vez, una vez única, quizás inmemorial, ajeno a las horas, en un aquí y un ahora del cual sólo usted podría dar testimonio; ¿qué?, una resina que no cicatriza, un ojo rayado que no ha perdido su lucidez (recordando palabras de Paul Celan) pero que capta las imágenes, algo, más bien “ningún” se ofrece al pensamiento: Ninguna voz, sólo su voz única: Su poesía. Por eso es que ella siempre tendrá lugar en la tierra: la tierra del corazón. Jonathan Alexander España Eraso Revista Cultural Avatares. * Es una poeta colombiana que imprime en sus versos una fuerte personalidad crítica, quizá algo enrevesada para el tiempo en que vivimos, influyente en corrientes filosóficas dispares (existencialismo y simbolismo, principalmente) que se nutren de la lírica asonante y categórica que utiliza. El ensayo poético, como método para llegar al fin, representa el quid pro quo de una joven poeta, ganadora de una beca de creación poética de la Casa de Poesía Silva en 2009, autora de antologías como Degustando palabras (2008) o de novelas, como una juvenil que piensa de publicar durante este 2011, nos dan ávida cuenta de que en literatura, lejos de saberse todo, todavía queda mucho por ver y descubrir". Reseña: ©Literatura del mañana

Thomas Chatterton (20 November 1752– 24 August 1770) was an English poet and forger of pseudo-medieval verse. Although fatherless and raised in poverty, he was an exceptionally studious child, publishing mature work by the age of eleven. He was able to pass-off as an imaginary 15th-century poet called Thomas Rowley, chiefly because few people at the time were familiar with medieval poetry, though he was denounced by Horace Walpole. At seventeen, he sought outlets for his political writings in London, having impressed the Lord Mayor, William Beckford, and the radical leader John Wilkes, but his earnings were not enough to keep him, and he poisoned himself in despair. His unusual life and death attracted much interest among the romantic poets, and Alfred de Vigny wrote a play about him that is still performed today. The oil-painting The Death of Chatterton by Pre-Raphaelite artist Henry Wallis has enjoyed lasting fame. Childhood Chatterton was born in Bristol where the office of sexton of St Mary Redcliffe had long been held by the Chatterton family. The poet’s father, also named Thomas Chatterton, was a musician, a poet, a numismatist, and a dabbler in the occult. He had been a sub-chanter at Bristol Cathedral and master of the Pyle Street free school, near Redcliffe church. After Chatterton’s birth (15 weeks after his father’s death on 7 August 1752), his mother established a girls’ school and took in sewing and ornamental needlework. Chatterton was admitted to Edward Colston’s Charity, a Bristol charity school, in which the curriculum was limited to reading, writing, arithmetic and the catechism. Chatterton, however, was always fascinated with his uncle the sexton and the church of St Mary Redcliffe. The knights, ecclesiastics and civic dignitaries on its altar tombs became familiar to him. Then he found a fresh interest in oaken chests in the muniment room over the porch on the north side of the nave, where parchment deeds, old as the Wars of the Roses, lay forgotten. Chatterton learned his first letters from the illuminated capitals of an old musical folio, and he learned to read out of a black-letter Bible. He did not like, his sister said, reading out of small books. Wayward from his earliest years, and uninterested in the games of other children, he was thought to be educationally backward. His sister related that on being asked what device he would like painted on a bowl that was to be his, he replied, “Paint me an angel, with wings, and a trumpet, to trumpet my name over the world.” From his earliest years he was liable to fits of abstraction, sitting for hours in what seemed like a trance, or crying for no reason. His lonely circumstances helped foster his natural reserve, and to create the love of mystery which exercised such an influence on the development of his poetry. When Chatterton was six, his mother began to recognise his capacity; at eight he was so eager for books that he would read and write all day long if undisturbed; by the age of eleven, he had become a contributor to Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal. His confirmation inspired him to write some religious poems published in that paper. In 1763 a cross which had adorned the churchyard of St Mary Redcliffe for upwards of three centuries was destroyed by a churchwarden. The spirit of veneration was strong in Chatterton, and he sent to the local journal on 7 January 1764 a satire on the parish vandal. He also liked to lock himself in a little attic which he had appropriated as his study; and there, with books, cherished parchments, loot purloined from the muniment room of St Mary Redcliffe, and drawing materials, the child lived in thought with his 15th century heroes and heroines. First “medieval” works The first of his literary mysteries, the dialogue of “Elinoure and Juga,” was written before he was 12, and he showed it to Thomas Phillips, the usher at the boarding school Colston’s Hospital where he was a pupil, pretending it was the work of a 15th-century poet. Chatterton remained a boarder at Colston’s Hospital for more than six years, and it was only his uncle who encouraged the pupils to write. Three of Chatterton’s companions are named as youths whom Phillips’s taste for poetry stimulated to rivalry; but Chatterton told no one about his own more daring literary adventures. His little pocket-money was spent on borrowing books from a circulating library; and he ingratiated himself with book collectors, in order to obtain access to John Weever, William Dugdale and Arthur Collins, as well as to Thomas Speght’s edition of Chaucer, Spenser and other books. At some point he came across Elizabeth Cooper’s anthology of verse, which is said to have been a major source for his inventions. Chatterton’s “Rowleian” jargon appears to have been chiefly the result of the study of John Kersey’s Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, and it seems his knowledge even of Chaucer was very slight. His holidays were mostly spent at his mother’s house, and much of them in the favourite retreat of his attic study there. He lived for the most part in an ideal world of his own, in the reign of Edward IV, during the mid-15th century, when the great Bristol merchant William II Canynges (d.1474), five times mayor of Bristol, patron and rebuilder of St Mary Redcliffe “still ruled in Bristol’s civic chair.” Canynges was familiar to him from his recumbent effigy in Redcliffe church, and is represented by Chatterton as an enlightened patron of art and literature. Adopts persona of Thomas Rowley Chatterton soon conceived the romance of Thomas Rowley, an imaginary monk of the 15th century, and adopted for himself the pseudonym Thomas Rowley for poetry and history. According to psychoanalyst Louise J. Kaplan, his being fatherless played a great role in his imposturous creation of Rowley. The development of his masculine identity was held back by the fact that he was raised by two women: his mother Sarah and his sister Mary. Therefore, “to reconstitute the lost father in fantasy,” he unconsciously created "two interweaving family romances [fantasies], each with its own scenario." The first of these was the romance of Rowley for whom he created a fatherlike, wealthy patron, William Canynge, while the second was as Kaplan named it his romance of “Jack and the Beanstalk.” He imagined he would become a famous poet who by his talents would be able to rescue his mother from poverty. Chatterton’s search for a patron To bring his hopes to life, Chatterton started to look for a patron. At first, he was trying to do so in Bristol where he became acquainted with William Barrett, George Catcott and Henry Burgum. He assisted them by providing Rowley transcripts for their work. The antiquary William Barrett relied exclusively on these fake transcripts when writing his History and Antiquities of Bristol (1789) which became an enormous failure. But since his Bristol patrons were not willing to pay him enough, he turned to the wealthier Horace Walpole. In 1769 Chatterton sent specimens of Rowley’s poetry and “The Ryse of Peyncteynge yn Englade” to Walpole who offered to print them “if they have never been printed.” Later, however, finding that Chatterton was only sixteen and that the alleged Rowley pieces might have been forgeries, he scornfully sent him away. Political writings Badly hurt by Walpole’s snub, Chatterton wrote very little for a summer. Then, after the end of the summer, he turned his attention to periodical literature and politics, and exchanged Farley’s Bristol Journal for the Town and Country Magazine and other London periodicals. Assuming the vein of the pseudonymous letter writer Junius—then in the full blaze of his triumph—he turned his pen against the Duke of Grafton, the Earl of Bute and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, the Princess of Wales. Determines on leaving Bristol He had just dispatched one of his political diatribes to the Middlesex Journal, when he sat down on Easter Eve, 17 April 1770, and penned his “Last Will and Testament,” a satirical compound of jest and earnest, in which he intimated his intention of ending his life the following evening. Among his satirical bequests, such as his “humility” to the Rev. Mr Camplin, his “religion” to Dean Barton, and his “modesty” along with his “prosody and grammar” to Mr Burgum, he leaves “to Bristol all his spirit and disinterestedness, parcels of goods unknown on its quay since the days of Canynge and Rowley.” In more genuine earnestness he recalls the name of Michael Clayfield, a friend to whom he owed intelligent sympathy. The will was possibly prepared in order to frighten his master into letting him go. If so, it had the desired effect. John Lambert, the attorney to whom he was apprenticed, cancelled his indentures; his friends and acquaintances having donated money, Chatterton went to London. London Chatterton was already known to the readers of the Middlesex Journal as a rival of Junius, under the nom de plume of Decimus. He had also been a contributor to Hamilton’s Town and Country Magazine, and speedily found access to the Freeholder’s Magazine, another political miscellany supportive of John Wilkes and liberty. His contributions were accepted, but the editors paid little or nothing for them. He wrote hopefully to his mother and sister, and spent his first earnings in buying gifts for them. Wilkes himself had noted his trenchant style “and expressed a desire to know the author”; and Lord Mayor William Beckford graciously acknowledged a political address of his, and greeted him “as politely as a citizen could.” He was abstemious and extraordinarily diligent. He could assume the style of Junius or Tobias Smollett, reproduce the satiric bitterness of Charles Churchill, parody James Macpherson’s Ossian, or write in the manner of Alexander Pope or with the polished grace of Thomas Gray and William Collins. He wrote political letters, eclogues, lyrics, operas and satires, both in prose and verse. In June 1770—after nine weeks in London—he moved from Shoreditch, where he had lodged with a relative, to an attic in Brook Street, Holborn (now beneath Alfred Waterhouse’s Holborn Bars building). He was still short of money; and now state prosecutions of the press rendered letters in the Junius vein no longer admissible, and threw him back on the lighter resources of his pen. In Shoreditch, he had shared a room; but now, for the first time, he enjoyed uninterrupted solitude. His bed-fellow at Mr Walmsley’s, Shoreditch, noted that much of the night was spent by him in writing; and now he could write all night. The romance of his earlier years revived, and he transcribed from an imaginary parchment of the old priest Rowley his “Excelente Balade of Charitie.” This poem, disguised in archaic language, he sent to the editor of the Town and Country Magazine, where it was rejected. Mr Cross, a neighbouring apothecary, repeatedly invited him to join him at dinner or supper; but he refused. His landlady also, suspecting his necessity, pressed him to share her dinner, but in vain. “She knew,” as she afterwards said, “that he had not eaten anything for two or three days.” But he assured her that he was not hungry. The note of his actual receipts, found in his pocket-book after his death, shows that Hamilton, Fell and other editors who had been so liberal in flattery, had paid him at the rate of a shilling for an article, and less than eightpence each for his songs; much which had been accepted was held in reserve and still unpaid for. According to his foster-mother, he had wished to study medicine with Barrett, and in his desperation he wrote to Barrett for a letter to help him to an opening as a surgeon’s assistant on board an African trader. Death While walking along St Pancras Churchyard, Chatterton much absorbed in thought, took no notice of an open grave, newly dug in his path, and subsequently tumbled into it. His walking companion upon observing this event, helped Chatterton out and told him in a jocular manner, that he was happy in assisting at the resurrection of genius. Chatterton replied, “My dear friend, I have been at war with the grave for some time now.” Chatterton would commit suicide three days later. On 24 August 1770, he retired for the last time to his attic in Brook Street, carrying with him the arsenic which he drank, after tearing into fragments whatever literary remains were at hand. He was only 17 years and nine months old. A few days later one Dr Thomas Fry came to London with the intention of giving financial support to the young boy “whether discoverer or author merely.” A fragment, probably one of the last pieces written by the impostor-poet was put together by Dr Fry from the shreds of paper that covered the floor of Thomas Chatterton’s Brook Street attic on the morning of 25 August 1770. The would-have-been patron of the poet had an eye for literary forgeries, and purchased the scraps which the poet’s landlady, Mrs Angel swept into a box, cherishing the hope of discovering a suicide note among the pieces. This fragment, possibly one of the remnants of Chatterton’s very last literary efforts, was identified by Dr Fry to be a modified ending of the poet’s tragical interlude Aella. The fragment is now in the possession of Bristol Public Library and Art Gallery. The final Alexandrine is completely missing, together with Chatterton’s notes. However, according to Dr Fry, the character who utters the final lines must have been Birtha, whose last word might have been something like “kisste.” Posthumous recognition The death of Chatterton attracted little notice at the time; for the few who then entertained any appreciative estimate of the Rowley poems regarded him as their mere transcriber. He was interred in a burying-ground attached to the Shoe Lane Workhouse, in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, later the site of Farringdon Market. There is a discredited story that the body of the poet was recovered, and secretly buried by his uncle, Richard Phillips, in Redcliffe Churchyard. There a monument has since been erected to his memory, with the appropriate inscription, borrowed from his “Will,” and so supplied by the poet’s own pen. “To the memory of Thomas Chatterton. Reader! judge not. If thou art a Christian, believe that he shall be judged by a Superior Power. To that Power only is he now answerable.” It was after Chatterton’s death that the controversy over his work began. Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others, in the Fifteenth Century (1777) was edited by Thomas Tyrwhitt, a Chaucerian scholar who believed them genuine medieval works. However, the appendix to the following year’s edition recognises that they were probably Chatterton’s own work. Thomas Warton, in his History of English Poetry (1778) included Rowley among 15th-century poets, but apparently did not believe in the antiquity of the poems. In 1782 a new edition of Rowley’s poems appeared, with a “Commentary, in which the antiquity of them is considered and defended,” by Jeremiah Milles, Dean of Exeter. The controversy which raged round the Rowley poems is discussed in Andrew Kippis, Biographia Britannica (vol. iv., 1789), where there is a detailed account by G Gregory of Chatterton’s life (pp. 573–619). This was reprinted in the edition (1803) of Chatterton’s Works by Robert Southey and Joseph Cottle, published for the benefit of the poet’s sister. The neglected condition of the study of earlier English in the 18th century alone accounts for the temporary success of Chatterton’s mystification. It has long been agreed that Chatterton was solely responsible for the Rowley poems; the language and style were analysed in confirmation of this view by W. W. Skeat in an introductory essay prefaced to vol. ii. of The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton (1871) in the “Aldine Edition of the British Poets.” The Chatterton manuscripts originally in the possession of William Barrett of Bristol were left by his heir to the British Museum in 1800. Others are preserved in the Bristol library. Legacy Chatterton’s genius and his death are commemorated by Percy Bysshe Shelley in Adonais (though its main emphasis is the commemoration of Keats), by William Wordsworth in “Resolution and Independence,” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in “Monody on the Death of Chatterton,” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in “Five English Poets,” and in John Keats’ sonnet “To Chatterton.” Keats also inscribed Endymion “to the memory of Thomas Chatterton.” Two of Alfred de Vigny’s works, Stello and the drama Chatterton, give fictionalized accounts of the poet; in the former, there is a scene in which William Beckford’s harsh criticism of Chatterton’s work drives the poet to suicide. The three-act play “Chatterton” was first performed at the Théâtre-Français, Paris on February 12, 1835. Herbert Croft, in his Love and Madness, interpolated a long and valuable account of Chatterton, giving many of the poet’s letters, and much information obtained from his family and friends (pp. 125–244, letter li.). The most famous image of Chatterton in the 19th century was The Death of Chatterton (1856) by Henry Wallis, now in Tate Britain, London. Two smaller versions, sketches or replicas, are held by the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and the Yale Center for British Art. The figure of the poet was modelled by the young George Meredith. Two of Chatterton’s poems were set to music as glees by the English composer John Wall Callcott. These include separate settings of distinct verses within the Song to Aelle. His best known poem, O synge untoe mie roundelaie was set to a five-part madrigal by Samuel Wesley. Chatterton has attracted operatic treatment a number of times throughout history, notably Ruggiero Leoncavallo’s largely unsuccessful two-act Chatterton; the German composer Matthias Pintscher’s modernistic Thomas Chatterton; and Australian composer Matthew Dewey’s lyrical yet dramatically intricate one-man mythography entitled “The Death of Thomas Chatterton.” There is a collection of “Chattertoniana” in the British Museum, consisting of works by Chatterton, newspaper cuttings, articles dealing with the Rowley controversy and other subjects, with manuscript notes by Joseph Haslewood, and several autograph letters. E. H. W. Meyerstein, who worked for many years in the manuscript room of the British Museum wrote a definitive work—"A Life of Thomas Chatterton"—in 1930. Peter Ackroyd’s 1987 novel Chatterton was a literary re-telling of the poet’s story, giving emphasis to the philosophical and spiritual implications of forgery. In 1886, architect Herbert Horne and Oscar Wilde unsuccessfully attempted to have a plaque erected at Colston’s School, Bristol. Wilde, who lectured on Chatterton at this time, suggested the inscription: “To The Memory of Thomas Chatterton, One of England’s Greatest Poets, and Sometime pupil at this school.” In 1928 a plaque in memory of Chatterton was mounted on 39, Brooke Street, Holborn, bearing the inscription below. The plaque has subsequently been transferred to a modern office building on the same site. Within Bromley Common, there is a road called Chatterton Road; this is the main thoroughfare in Chatterton Village, based around the public house, The Chatterton Arms. Both road and pub are named after the poet. French singer Serge Gainsbourg entitled one of his songs “Chatterton,” stating: Chatterton suicidé Hannibal suicidé [...] Quant à moi Ça ne va plus très bien. The song was covered (in Portuguese) by Seu Jorge live and recorded in the album Ana & Jorge: Ao Vivo. Works * ‘An Elegy on the much lamented Death of William Beckford, Esq.,’ 4to, pp. 14, 1770. * 'The Execution of Sir Charles Bawdwin’ (edited by Thomas Eagles, F.S.A.), 4to, pp. 26, 1772. * 'Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol, by Thomas Rowley and others, in the Fifteenth Century’ (edited by Thomas Tyrwhitt), 8vo, pp. 307, 1777. * 'Appendix’ (to the 3rd edition of the poems, edited by the same), 8vo, pp. 309–333, 1778. * 'Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, by Thomas Chatterton, the supposed author of the Poems published under the names of Rowley, Canning, &c.' (edited by John Broughton), 8vo, pp. 245, 1778. * 'Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol in the Fifteenth Century by Thomas Rowley, Priest, &c., [edited] by Jeremiah Milles, D.D., Dean of Exeter,' 4to, pp. 545, 1782. * ‘A Supplement to the Miscellanies of Thomas Chatterton,’ 8vo, pp. 88, 1784. * 'Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others in the Fifteenth Century’ (edited by Lancelot Sharpe), 8vo, pp. xxix, 329, 1794. * ‘The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton,’ Anderson s ‘British Poets,’ xi. 297-322, 1795. * ‘The Revenge: a Burletta ; with additional Songs, by Thomas Chatterton,’ 8vo, pp. 47, 1795. * 'The Works of Thomas Chatterton’ (edited by Robert Southey and Joseph Cottle), 3 vols. 8yo, 1803. * 'The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton’ (edited by Charles B. Willcox), 2 vols. 12mo, 1842. * 'The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton’ (edited by the Rev Walter Skeat, M.A.), Aldine edition, 2 vols. 8vo, 1875. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Chatterton

Arthur Chapman (June 25, 1873– December 4, 1935) was an early twentieth-century American poet and newspaper columnist. He wrote a subgenre of American poetry known as Cowboy Poetry. His most famous poem was Out Where the West Begins. Out Where the West Begins Circa 1910, after reading in an Associated Press report of a conference of the governors of the western states at which the geographic beginning of the U.S. West was disputed, he hastily composed what was to become his most famous poem, “Out Where the West Begins,” celebrating the people and the land of the frontier. The first of its three seven-line stanzas ran "Out where the handclasp’s a little stronger, / Out where the smile dwells a little longer, / That’s where the West begins; / Out where the sun is a little brighter, / Where the snows that fall are a trifle whiter, / Where the bonds of home are a wee bit tighter, / That’s where the West begins." The poem was an immediate sensation, widely quoted, often imitated, and more often parodied. (One popular anonymous take-off read, in part, "Where the women boss and the men folk think / That toast is food and tea is a drink; / Where the men use powder and the wrist watch ticks, / And everyone else but themselves are hicks / That’s where the East begins.") According to the dust jacket of Chapman’s 1921 novel, Mystery Ranch, "To-day ["Out Where the West Begins"] is perhaps the best-known bit of verse in America. It hangs framed in the office of the Secretary of the Interior at Washington. It has been quoted in Congress, and printed as campaign material for at least two Governors. . . . [Chapman’s poems possess] a rich Western humor such as had not been heard in American poetry since the passing of Bret Harte.” The popularity of “Out Where the West Begins” led Chapman to arrange for its publication in book form, and in 1916 he produced Out Where the West Begins, and Other Small Songs of a Big Country, a modest fifteen-page volume issued by Carson-Harper in Denver. It was an immediate success and Houghton Mifflin of Boston and New York immediately offered to publish a larger collection. Out Where the West Begins, and Other Western Verses, as it was renamed, appeared in 1917 with fifty-eight poems on ninety-two pages. The title poem was widely reprinted on postcards and plaques. It was frequently set to music, first in 1920, and achieved a separate life on the concert stage. Chapman followed the popular volume in 1921 with the equally successful Cactus Center: Poems of an Arizona Town, containing thirty poems and running to 123 pages. The Literary Review wrote of the verse, "In vigor of style, [it] irresistibly suggests a transplanted Kipling" (19 Feb. 1921, p. 12). The Move East In 1919 Chapman moved to New York City, where he lived in a fashionable neighborhood on the east side of Manhattan and took a job as a staff writer for the Sunday edition of the New York Tribune. He held that position until his retirement in 1925, the year after the newspaper became the New York Herald Tribune. After his wife died in 1923 Chapman married Kathleen Caesar, an editor of the Bell Syndicate; no children were born of his second marriage. He wrote fiction and nonfiction throughout his career as a journalist and continued after he retired. His first effort at book-length fiction, Mystery Ranch (1921), combined the genres of western adventure and murder mystery. The Literary Review dismissed it as “melodramatic” and stated that it provided “little for the seeker of literary values” (19 Nov. 1921, p. 190), but the New York Times more charitably credited Chapman, “known heretofore as a poet of the West,” with being “a clever technician in a new field” (13 Nov. 1921). The book had modest commercial success, but Chapman’s second novel, John Crews (1926), an equally stereotypical adventure-romance of frontier life, sold better. Described by the New York Herald Tribune as “a lively and continuously readable yarn,” it was successful enough to have a reprint edition by another publisher in its first year (28 Mar. 1926). In 1924 Chapman capitalized on his reputation as an expert on the U.S. West with the publication of The Story of Colorado, Out Where the West Begins, a richly illustrated history of the state. His final book was an extensively researched and detailed volume, The Pony Express: The Record of a Romantic Adventure in Business (1932), complete with bibliography, index, and maps. Both were well received by the critics and the public. It was, however, for his poetry that Chapman became and remained famous. His western dialect poems and “Out Where the West Begins” continued to be quoted and to appear in anthologies long after his death, and both of his volumes of verse were brought out in new editions by other publishers as late as 2010. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Chapman_(poet)

I grew up in the small town of North Fork, California. I graduated from California State University, Fresno in Spring, 2011 with a B.A. in Mass Communications. I completed two years of my television work experience by working for WQAD News 8 (Moline, IL) as a production assistant, Video editor, and Photographer. I'm currently back in North Fork and continuing work with Vendetta Pro Wrestling, while also writing poetry. Besides writing poetry and professional wrestling, I have filmed and edited a variety of other things. These include documentaries, weddings, graduations, commercials, short movies, and other sports. I hope my Poetry lights up someone's day or helps them in some other way, Because the world passes you by so fast that it could lead some people astray.

Aprendiz y estudiante del arte y de la vida de medio tiempo y escritora y dibujante de tiempo completo (no profesional), sin embargo es uno de mis sueños, por esta razón es que escribo y me gustaría que más gente me ayudara a volverlo realidad, ya que lamentablemente dependo de ello. "Escribo para vivir y vivo para escribir". Entré a este sitio buscando material para matar el tiempo, pero terminó siendo parte de mi vida, ojalá no se vuelva tan importante como para volverse más que una parte de mi vida, parte de mi ser, después de todo no importa, pasar gran parte del día escribiendo en vez de hacer algo con mi vida es un mal hábito que me alegra tener, y definitivamente adentrarte en el mundo de la poesía es como una droga, una vez que lo has probado ya no puedes salir de ella, es como estar drogado sin drogarte, y esa sensación para mí es de las más asombrosas que puedes experimentar en la vida.

William Wilfred Campbell (15 June 1860– 1 January 1918) was a Canadian poet. He is often classed as one of the country’s Confederation Poets, a group that included fellow Canadians Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, and Duncan Campbell Scott; he was a colleague of Lampman and Scott. By the end of the 19th century, he was considered the “unofficial poet laureate of Canada.” Although not as well known as the other Confederation poets today, Campbell was a “versatile, interesting writer” who was influenced by Robert Burns, the English Romantics, Edgar Allan Poe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Thomas Carlyle, and Alfred Tennyson. Inspired by these writers, Campbell expressed his own religious idealism in traditional forms and genres. Life William Wilfred Campbell was born around 15 June 1860 in Newmarket, Upper Canada (present-day Ontario). There is some doubt as to the date and place of his birth. His father, Rev. Thomas Swainston Campbell, was an Anglican clergyman who had been assigned the task of setting up several frontier parishes in “Canada West”, as Ontario was then called. Consequently, the family moved frequently. The Campbell family settled in Wiarton, Ontario in 1871, where Wilfred grew up, attending high school (which was later renamed the Owen Sound Collegiate and Vocational Institute) in nearby Owen Sound. Campbell would look back on his childhood with fondness: As a boy, I always enjoyed the campfires we built in the woods or on the shingly beach of some lone lake shore, when the stars came out and peered down on the windy darkness and swallowed up the sparks and flames from the crackling logs and dry branches we heaped up while the local warmth and radiance added a contrast to the outside vastness of darkness and cold. Campbell taught in Wiarton before enrolling in the University of Toronto’s University College in 1880, Wycliffe College in 1882, and at the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1883. Campbell married Mary DeBelle (née Dibble) in 1884. They had four children, Margery, Faith, Basil, and Dorothy. In 1885 Campbell was ordained to the Episcopal priesthood, and was soon appointed to a New England parish. In 1888 he returned to Canada and became rector of St. Stephen, New Brunswick. In 1891, after suffering a crisis of faith, Campbell resigned from the ministry and took a civil service position in Ottawa. He received a permanent position in the Department of Militia and Defence two years later. Living in Ottawa, Campbell became acquainted with Archibald Lampman—his next door neighbor at one time—and through him with Duncan Campbell Scott. In February 1892, Campbell, Lampman, and Scott began writing a column of literary essays and criticism called “At the Mermaid Inn” for the Toronto Globe. As Lampman wrote to a friend: Campbell is deplorably poor.... Partly in order to help his pockets a little Mr. Scott and I decided to see if we could get the Toronto Globe to give us space for a couple of columns of paragraphs & short articles, at whatever pay we could get for them. They agreed to it; and Campbell, Scott and I have been carrying on the thing for several weeks now. The column ran only until July 1893. Lampman and Scott found it difficult to “keep a rein on Campbell’s frank expression of his heterodox opinions.” Readers of the Toronto Globe reacted negatively when Campbell presented the history of the cross as a mythic symbol. His apology for “overestimating their intellectual capacities” did little to resolve the controversy. In the 20th century, Campbell became a strong advocate of British imperialism, for example telling Toronto’s Empire Club in 1904 that Canada’s only choice lay “between two different imperialisms, that of Britain and that of the Imperial Commonwealth to the south.” It was the principles of Imperialist that guided his work in Poems of loyalty by British and Canadian authors (London, 1913) and for The Oxford Book of Canadian Verse (Toronto, 1913). As editor of The Oxford book of Canadian Verse, Campbell devoted more pages to his own poetry than to others’. But by choosing mostly from his longer work—including an excerpt from Mordred (one of his verse dramas)—he did not choose his best work. In contrast, the poems he selected from his fellow Confederation Poets reflected some of their best work. Campbell was transferred to the Dominion Archives in 1909. In 1915 he moved his family to an old stone farmhouse on the outskirts of Ottawa, which he named “Kilmorie”. He died of pneumonia on New Year’s morning, 1918. He was buried in Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery. Writing Campbell’s first chapbook, Poems!, "seems to have been printed at a newspaper office sometime around 1879 or 1880." He placed poetry in the University of Toronto Varsity in 1881. As a theology student in Massachusetts, Campbell met Oliver Wendell Holmes, who recommended his poetry to Atlantic Monthly editor Thomas Bailey Aldrich. Aldrich published Campbell’s “Canadian Folk Song” in the January 1885 issue, launching his career in the American magazines. In 1888 Snowflakes and Sunbeams was printed at Campbell’s expense in St. Stephen, New Brunswick. The book "was favourably reviewed in Canada and the United States for its lovely nature lyrics, one of which, 'Indian summer’ (it starts with 'Along the line of smoky hills / The crimson forest stands’), remains among the most beloved of Canadian poems." The entire volume, including “Indian Summer,” was incorporated into Lake Lyrics, published the following year. "The poems in Lake lyrics and other poems (1889), with their intense rhythms, dramatic imagery, and ardent spirituality, express Campbell’s devotion to nature as the revelation of God’s presence; this book established his reputation as ‘laureate of the lakes.’" Notable new poems in the book included “Vapor and Blue” and “The Winter Lakes”. Campbell’s poem “The Mother” was printed in Harper’s New Monthly in April 1891; a traditional ballad, the poem tells of a dead mother who rises from the grave to claim her still-living baby. It "created a sensation in the literary press and was reprinted in newspapers such as the Week and the Globe in Toronto. In September 1881, the House of Commons (and, in 1892, the Senate) debated whether Campbell should receive a permanent civil service position in recognition of his literary abilities. The proposal was defeated, ostensibly for practical reasons, and the decision established a precedent for withholding patronage from artists. Nevertheless, in 1893 he was quietly given a permanent position in the Department of Militia and Defence, and he would remain a civil servant until his death." Campbell’s third book of poetry, The Dread Voyage Poems (1893), was darker than the earlier two. “In this volume, his poetry began to show the preoccupation with harmonizing religion, science, and social theory that had started while he was still a clergyman and would continue through his middle age.” The book contains some of Campbell’s best-known poems, such as “How One Winter Came in the Lake Region” and the 'surprise ending’ sonnet, “Morning on the Shore.” “In 1895 he published two versified tragedies, Mordred and Hildebrand, and these were included, with two others, Daulac and Morning, in a volume entitled Poetical tragedies (1908)." Also in 1895, Campbell sparked a literary controversy by accusing Bliss Carman of plagiarism, an incident documented in Alexandra Hurst’s 1994 book, The War Among the Poets (Canadian Poetry Press). Campbell published a new book of lyrics, Beyond the Hills of Dream, in 1899. "Included in the book was his jubilee ode ‘Victoria,’ written for the Queen’s diamond jubilee in 1897. Eleven of its thirty-five other poems were reprinted from The Dread Voyage, thus perpetuating the dark tone of the earlier volume. Sombre also was “Bereavement of the Fields,” one of the better new poems, written in memory of Archibald Lampman, who died on 10 February 1899.” “The early years of the twentieth century saw a prolific outpouring of prose from Campbell. In addition to numerous pamphlets, he wrote five historical novels and three works of non-fiction. Only two of his novels ever appeared in book form: Ian of the Orcades (1906)... and A Beautiful Rebel (1909). Another novel was never re-printed after its appearance in The Christian Guardian, and two novels still remain only in manuscript form. Two of his works of non-fiction were labours of love: a book about the Great Lakes (1910, reprinted and enlarged 1914), and an account of the Scottish settlements in Eastern Canada (1911). The title of the former is quite a mouthful: The Beauty, History, Romance, and Mystery of the Canadian Lake Region. Campbell intersperses these descriptive sketches, which appeared originally in The Westminster magazine, with selections of his lake lyrics to give the reader a very personal tour of the region. Subjective, also, is the bias of The Scotsman in Canada, which credits Scots with laying the foundation of nearly everything that is admirable in Canada.” In 1914, with war threatening, Campbell published a book of imperialistic verse, Sagas of a Vaster Britain. "Many of its seventy poems were recycled from previous collections, patriotic effusions like “England” (“Over the freedom and peace of the world/ Is the flag of England flung”), and some of his best work like “How One Winter Came to the Lake Region". The new poems, like “Life’s Ocean” and “The Dream Divine,” have the old weaknesses of displeasing sound (“large-mooned waters”) and awkward structure (“And of all love’s far, dim dawnings of hope unborn/ God’s latest are best”)." "Sagas... was his last book, but each New Year’s from 1915 to 1918 he distributed pamphlets of poems relating to World War I.” When Campbell died in 1918, his “popularity died with him. Technically, his work is usually conservative, and his ideas have become unfashionable. His poetry has been compared with the more polished works” of the four major Confederation poets. “In fact,” though, as the DCB sums up his career, “Campbell worked hard to achieve naturalness, sincerity, and simplicity of expression, rather than polish; he tried to convey universal truths in order to inspire his readers to strive toward their noblest ideals. Within this framework, the artistic merit of many of his poems becomes evident.” Campbell was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1894. He was declared a Person of National Historic Significance in 1938. Bibliography * Poetry * Poems! (1879-1880?) * Snowflakes and sunbeams. St. Stephen, N.B.: St. Croix Courier Press, 1888 (reprinted Ottawa, 1974) * Lake lyrics and other poems. Saint John: J.& A. McMillan, 1889 * The dread voyage poems. Toronto: William Briggs, 1893 * Mordred and Hildebrand: A Book of Tragedies.. Ottawa: J. Durie, 1895 * Beyond the hills of dream. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1899. and Toronto, 1900 * The poems of Wilfred Campbell. Toronto: William Briggs, 1905 * The collected poems of Wilfred Campbell. New York, 1905 * Poetical tragedies. Toronto: William Briggs, 1908 * Sagas of vaster Britain: poems of the race, the empire and the divinity of man. Toronto: Musson, 1914 * The poetical works of Wilfred Campbell. W.J. Sykes ed. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1923. * Selected Poems. 1976 * Vapour and Blue. Souster selects Campbell: The poetry of William Wilfred Campbell. Raymond Souster ed. Sutton: Paget, 1978 * William Wilfred Campbell: selected poetry and essays. Laurel Boone ed. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier U P, 1987 * Fiction * Ian of the Orcades; or, the armourer of Girnigoe. Edinburgh and London, 1906. New York, 1906 * A beautiful rebel: a romance of Upper Canada in 1812. Toronto, 1909 New York and London, 1909 * Non-fiction * Canada. text to Thomas Mower Martin’s Illustrations in Canada. Toronto: Macmillan, 1907. (London, 1907) * The beauty, history, romance and mystery of the Canadian lake region. Toronto, 1910. (new ed., 1914) * The Scotsman in Canada vol. 1. London: Sampson Low Marston & Co., 1912. Toronto, 1911 * At the Mermaid Inn: Wilfred Campbell, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott in the Globe 1892–3, ed. Barrie Davies (Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1979 * Edited works * The Oxford Book of Canadian Verse (1913) * Poems of Loyalty by British and Canadian Authors (1913) * Except where noted, bibliographic information courtesy of Dictionary of Canadian Biography. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wilfred_Campbell

Chávez Mercado, Rodolfo de Jesús nació en Cartagena, Bolívar, Colombia, 14.08.1981. Sacerdote. Licenciado en Teología Fundamental. Amante de la literatura. Se destacan sus obras literarias en el portal de Naciones Unidas de las Letras. Ha publicado sus poemas en revistas literarias internacionales, “Pluma y Tintero” España; “Orizont Literar Contemporan” Rumania. y “Palabras Diversas”. Remes., entre otras. Libros publicados: Ardiendo en Esperanza, poemas que enamoran la tarde. Editorial Círculo Rojo.2014 Osadía, Editorial Ave Viajera. 2016 Página web del autor: http://www.elsentirdeunalma.blogspot.com, Correo electrónico : [email protected]

Jorge Mateo Cuesta Porte-Petit (1903-1942) fue un químico, poeta, ensayista y editor mexicano. Nació en Córdoba, Veracruz, en donde realizó sus primeros estudios. En la Ciudad de México estudió la carrera de ciencias químicas. En 1927 conoció a Guadalupe Marín (entonces esposa del pintor Diego Rivera), que más tarde sería su esposa, y ese mismo año publicó su polémica Antología de la poesía mexicana moderna. En 1928 viajó a Europa, donde estuvo en contacto con André Breton, Carlos Pellicer, Samuel Ramos y Agustín Lazo. A partir de 1930 formó parte del grupo Los contemporáneos, quienes lo llamaron "El Alquimista". Su poesía es descarnada, racionalista, utiliza como temas la ansiedad, el pesimismo, la vejez, la muerte, el equilibrio, etc. Privilegió la forma del soneto. Su poema más ambicioso y mejor logrado es "Canto a un dios mineral", que es agrupado por la crítica en la tradición mexicana del poema filosófico junto con "Primero Sueño" de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, "Muerte sin fin" de José Gorostiza, "Blanco" de Octavio Paz e "Incurable" de David Huerta. Colaboró en la Revista Ulises, El Universal, contemporáneos, Voz nacional, Letras de México y El Nacional. En 1932 fundó la revista Examen. Su poesía fue recopilada póstumamente en dos ediciones, una prologada por Alí Chumacero y otra por Elías Nandino y Rubén Salazar Mallén. En 1964 la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México publicó todo lo que se conoce de su obra poética y ensayística en cuatro volúmenes. Jorge Cuesta se quitó la vida el 13 de agosto de 1942 en el sanatorio del doctor Lavista, en Tlalpan. Tenía 38 años cuando, aprovechando un descuido de los enfermeros, se colgó con sus propias sábanas de los barrotes de la cama. Había sido internado por un segundo acceso de locura que lo había llevado a acuchillarse los genitales. Recaía en una crisis de paranoia que había superado en el Hospital Mixcoac dos años antes. Una noche, en un café, Cuesta dejó escrita la siguiente frase en un papel: "Porque me pareció poco suicidarme una sola vez. Una sola vez no era, no ha sido suficiente". Con el tiempo estas palabras se han convertido en profecía cumplida pues, efectivamente, el suicidio de Cuesta tiene que ser revivido por cada lector que se interna en su "Canto a un dios mineral" con el ánimo de entender este poema que ha sido calificado de "hermético". Porque, en realidad, como dijo Rubén Salazar Mallén, su poesía es oscura sólo para quienes no conocen su vida o, en palabras de Alí Chumacero, su poesía es poco diferente de lo que vivió. Referencias wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Cuesta

Back after such a long long time!! Things really do change!! Please don't expect good grammar, academic ability etc etc. school was a no go but...there always is one...my writings are as and when, easy, with words everyone understands...else...what's the point right?! ....in hindsight...maybe the point is "if I don't understand, I could try?!" but will I ... I'm no Bukowski...but the fact that I know of and Love his guts/writing/rebellion says it all. School....overrated "if you don't want your book to be judged by its cover...should you really write one?" Questions always gratefully received, my answers might not be" Music/book/film fiend...for fun! "it's just a ride" *Bill Hicks ABOVE ALL ELSE...MY LITERARY HERO..."The edge, there is no honest what to explain it because the only people who really know where it is are the ones that have gone over" *Hunter. S. Thompson

Arthur Hugh Clough (1 January 1819 – 13 November 1861) was an English poet, an educationalist, and the devoted assistant to ground-breaking nurse Florence Nightingale. He was the brother of suffragist Anne Clough, who became principal of Newnham College, Cambridge. He was born in Liverpool to James Butler Clough, a cotton merchant of Welsh descent, and Anne Perfect, from Pontefract in Yorkshire. In 1822 the family moved to the United States, and Clough’s early childhood was spent mainly in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1828 Clough and his older brother Charles returned to England to attend school in Chester.