Info

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (November 10, 1879– December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern singing poetry, as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted. Crushed by financial worry and in failing health from his six-month road trip, Lindsay sank into depression. While in New York in 1905 Lindsay turned to poetry in earnest. He tried to sell his poems on the streets. Self-printing his poems, he began to barter a pamphlet titled “Rhymes To Be Traded For Bread”, which he traded for food as a self-perceived modern version of a medieval troubadour. On December 5, 1931, he committed suicide by drinking a bottle of Lysol. His last words were: “They tried to get me; I got them first!”

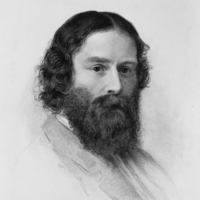

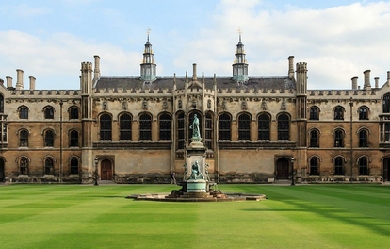

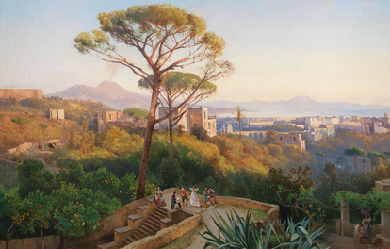

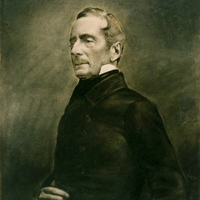

James Russell Lowell (/ˈloʊəl/; February 22, 1819– August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame. He went on to publish several other poetry collections and essay collections throughout his literary career. Maria White died in 1853, and Lowell accepted a professorship of languages at Harvard in 1854; he continued to teach there for twenty years. He traveled to Europe before officially assuming his role in 1856. He married his second wife, Frances Dunlap, shortly thereafter in 1857. That year Lowell also became editor of The Atlantic Monthly. It was not until 20 years later that Lowell received his first political appointment, the ambassadorship to the Kingdom of Spain. He was later appointed ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. He spent his last years in Cambridge, in the same estate where he was born, and died there in 1891. Lowell believed that the poet played an important role as a prophet and critic of society. He used poetry for reform, particularly in abolitionism. However, Lowell’s commitment to the anti-slavery cause wavered over the years, as did his opinion on African-Americans. Lowell attempted to emulate the true Yankee accent in the dialogue of his characters, particularly in The Biglow Papers. This depiction of the dialect, as well as Lowell’s many satires, was an inspiration to writers like Mark Twain and H.L. Mencken. Biography Early life The first of the Lowell family ancestors to come to the United States from Britain was Percival Lowle, who settled in Newbury, Massachusetts, in 1639. James Russell Lowell was born February 22, 1819, the son of the Reverend Charles Russell Lowell, Sr. (1782–1861), a minister at a Unitarian church in Boston, who had previously studied theology at Edinburgh, and Harriett Brackett Spence Lowell. By the time James Russell Lowell was born, the family owned a large estate in Cambridge called Elmwood. He was the youngest of six children; his siblings were Charles, Rebecca, Mary, William, and Robert. Lowell’s mother built in him an appreciation for literature at an early age, especially in poetry, ballads, and tales from her native Orkney. He attended school under Sophia Dana, who would later marry George Ripley, and later studied at a school run by a particularly harsh disciplinarian, where one of his classmates was Richard Henry Dana, Jr. Beginning in 1834, at the age of 15, Lowell attended Harvard College, though he was not a good student and often got into trouble. In his sophomore year alone, he was absent from required chapel attendance 14 times and from classes 56 times. In his last year there, he wrote, “During Freshman year, I did nothing, during Sophomore year I did nothing, during Junior year I did nothing, and during Senior year I have thus far done nothing in the way of college studies.” In his senior year, he became one of the editors of Harvardiana literary magazine, to which he contributed prose and poetry that he admitted was of low quality. As he said later, "I was as great an ass as ever brayed & thought it singing." During his undergraduate years, Lowell was a member of Hasty Pudding and served both as Secretary and Poet. Lowell was elected the poet of the class of 1838 and, as was tradition, was asked to recite an original poem on Class Day, the day before Commencement, on July 17, 1838. Lowell, however, was suspended and not allowed to participate. Instead, his poem was printed and made available thanks to subscriptions paid by his classmates. Lowell had composed the poem in Concord, Massachusetts, where, because of his neglect of his studies, he had been exiled by the Harvard faculty to the care of the Rev. Barzallai Frost. During his stay in Concord, he became friends with Ralph Waldo Emerson, and got to know the other Transcendentalists. The poem satirized the social movements of the day; abolitionists, Thomas Carlyle, Emerson, and the Transcendentalists were treated. Not knowing what vocation to choose after graduating, he vacillated among business, the ministry, medicine, and law. Having decided to practice law, he enrolled at Harvard Law School in 1840 and was admitted to the bar two years later. While studying law, however, he contributed poems and prose articles to various magazines. During this time, Lowell was admittedly depressed and often had suicidal thoughts. He once confided to a friend that he held a cocked pistol to his forehead and considered killing himself at the age of 20. Marriage and family In late 1839, Lowell met Maria White through her brother William, a classmate of his at Harvard, and the two became engaged in the autumn of 1840. Maria’s father Abijah White, a wealthy merchant from Watertown, insisted that their wedding be postponed until Lowell had gainful employment. They were finally married on December 26, 1844, shortly after the groom published Conversations on the Old Poets, a collection of his previously published essays. A friend described their relationship as “the very picture of a True Marriage.” Lowell himself believed she was made up “half of earth and more than half of Heaven.” Like Lowell, she wrote poetry, and the next twelve years of Lowell’s life were deeply affected by her influence. He said his first book of poetry, A Year’s Life (1841), “owes all its beauty to her,” though it only sold 300 copies. Her character and beliefs led her to become involved in the movements directed against intemperance and slavery. Maria was a member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and persuaded her husband to become an abolitionist. James had previously expressed antislavery sentiments, but Maria urged him towards more active expression and involvement. His second volume of poems, Miscellaneous Poems, expressed these antislavery thoughts and its 1,500 copies sold well. Maria was in poor health, and thinking her lungs could heal there, the couple moved to Philadelphia shortly after their marriage. In Philadelphia, he became a contributing editor for the Pennsylvania Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper. In the spring of 1845, the Lowells returned to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to make their home at Elmwood. They had four children, though only one (Mabel, born 1847) survived past infancy. Their first, Blanche, was born December 31, 1845, but lived only fifteen months; Rose, born in 1849, survived only a few months as well; their only son, Walter, was born in 1850 but died in 1852. Lowell was very affected by the loss of almost all of his children. His grief over the death of his first daughter in particular was expressed in his poem “The First Snowfall” (1847). Again, Lowell considered suicide, writing to a friend that he thought “of my razors and my throat and that I am a fool and a coward not to end it all at once.” Literary career Lowell’s earliest poems were published without remuneration in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1840. Lowell, inspired to new efforts towards self-support, joined with his friend Robert Carter in founding a literary journal, The Pioneer. The periodical was distinguished by the fact that most of its content was new rather than material that had been previously published elsewhere, and by the inclusion of very serious criticism, which covered not only literature but also art and music. Lowell wrote that it would “furnish the intelligent and reflecting portion of the Reading Public with a rational substitute for the enormous quantity of thrice-diluted trash, in the shape of namby-pamby love tales and sketches, which is monthly poured out to them by many of our popular Magazines.” William Wetmore Story noted the journal’s higher taste, writing that "it took some stand & appealled to a higher intellectual Standard than our puerile milk or watery namby-pamby Mags with which we are overrun." The first issue of the journal included the first appearance of “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe. Lowell, shortly after the first issue, was treated for an eye disease in New York, and in his absence Carter did a poor job of managing the journal. After three monthly numbers, beginning in January 1843, the magazine ceased publication, leaving Lowell $1,800 in debt. Poe mourned the journal’s demise, calling it “a most severe blow to the cause—the cause of a Pure Taste.” Despite the failure of The Pioneer, Lowell continued his interest in the literary world. He wrote a series on “Anti-Slavery in the United States” for the London Daily News, though his series was discontinued by the editors after four articles in May 1846. Lowell had published these articles anonymously, believing they would have more impact if they were not known to be the work of a committed abolitionist. In the spring of 1848 he formed a connection with the National Anti-Slavery Standard of New York, agreeing to contribute weekly either a poem or a prose article. After only one year, he was asked to contribute half as often to the Standard to make room for contributions from Edmund Quincy, another writer and reformer. A Fable for Critics, one of Lowell’s most popular works, was published in 1848. A satire, it was published anonymously. It proved popular, and the first three thousand copies sold out quickly. In it, Lowell took good-natured jabs at his contemporary poets and critics. Not all the subjects included were pleased, however. Edgar Allan Poe, who had been referred to as part genius and “two-fifths sheer fudge,” reviewed the work in the Southern Literary Messenger and called it “'loose’—ill-conceived and feebly executed, as well in detail as in general.... we confess some surprise at his putting forth so unpolished a performance.” Lowell offered the profits from the book’s success, which proved relatively small, to his New York friend Charles Frederick Briggs, despite his own financial needs. In 1848, Lowell also published The Biglow Papers, later named by the Grolier Club as the most influential book of 1848. The first 1,500 copies sold out within a week and a second edition was soon issued, though Lowell made no profit, having had to absorb the cost of stereotyping the book himself. The book presented three main characters, each representing different aspects of American life and using authentic American dialects in their dialogue. Under the surface, The Biglow Papers was also a denunciation of the Mexican–American War and war in general. First trip to Europe In 1850, Lowell’s mother died unexpectedly, as did his third daughter, Rose. Her death left Lowell depressed and reclusive for six months, despite the birth of his son Walter by the end of the year. He wrote to a friend that death “is a private tutor. We have no fellow-scholars, and must lay our lessons to heart alone.” These personal troubles as well as the Compromise of 1850 inspired Lowell to accept an offer from William Wetmore Story to spend a winter in Italy. To pay for the trip, Lowell sold land around Elmwood, intending to sell off further acres of the estate over time to supplement his income, ultimately selling off 25 of the original 30 acres (120,000 m2). Walter died suddenly in Rome of cholera, and Lowell and his wife, with their daughter Mabel, returned to the United States in October 1852. Lowell published recollections of his journey in several magazines, many of which would be collected years later as Fireside Travels (1867). He also edited volumes with biographical sketches for a series on British Poets. His wife Maria, who had been suffering from poor health for many years, became very ill in the spring of 1853 and died on October 27 of tuberculosis. Just before her burial, her coffin was opened so that her daughter Mabel could see her face while Lowell “leaned for a long while against a tree weeping,” according to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his wife, who were in attendance. In 1855, Lowell oversaw the publication of a memorial volume of his wife’s poetry, with only fifty copies for private circulation. Despite his self-described “naturally joyous” nature, life for Lowell at Elmwood was further complicated by his father becoming deaf in his old age, and the deteriorating mental state of his sister Rebecca, who sometimes went a week without speaking. He again cut himself off from others, becoming reclusive at Elmwood, and his private diaries from this time period are riddled with the initials of his wife. On March 10, 1854, for example, he wrote: "Dark without & within. M.L. M.L. M.L." Longfellow, a friend and neighbor, referred to Lowell as “lonely and desolate.” Professorship and second marriage At the invitation of his cousin John Amory Lowell, James Russell Lowell was asked to deliver a lecture at the prestigious Lowell Institute. Some speculated the opportunity was because of the family connection, offered as an attempt to bring him out of his depression. Lowell chose to speak on “The English Poets,” telling his friend Briggs that he would take revenge on dead poets “for the injuries received by one whom the public won’t allow among the living.” The first of the twelve-part lecture series was to be on January 9, 1855, though by December, Lowell had only completed writing five of them, hoping for last-minute inspiration. His first lecture was on John Milton and the auditorium was oversold; Lowell had to give a repeat performance the next afternoon. Lowell, who had never spoken in public before, was praised for these lectures. Francis James Child said that Lowell, whom he deemed was typically “perverse,” was able to “persist in being serious contrary to his impulses and his talents.” While his series was still in progress, Lowell was offered the Smith Professorship of Modern Languages at Harvard, a post vacated by Longfellow, at an annual salary of $1,200, though he never applied for it. The job description was changing after Longfellow; instead of teaching languages directly, Lowell would supervise the department and deliver two lecture courses per year on topics of his own choosing. Lowell accepted the appointment, with the proviso that he should have a year of study abroad. He set sail on June 4 of that year, leaving his daughter Mabel in the care of a governess named Frances Dunlap. Abroad, he visited Le Havre, Paris, and London, spending time with friends including Story, Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Leigh Hunt. Primarily, however, Lowell spent his time abroad studying languages, particularly German, which he found difficult. He complained: “The confounding genders! If I die I shall have engraved on my tombstone that I died of der, die, das, not because I caught them but because I couldn’t.” He returned to the United States in the summer of 1856 and began his college duties. Towards the end of his professorship, then-president of Harvard Charles William Eliot noted that Lowell seemed to have “no natural inclination” to teach; Lowell agreed, but retained his position for twenty years. He focused on teaching literature, rather than etymology, hoping that his students would learn to enjoy the sound, rhythm, and flow of poetry rather than the technique of words. He summed up his method: “True scholarship consists in knowing not what things exists, but what they mean; it is not memory but judgment.” Still grieving the loss of his wife, during this time Lowell avoided Elmwood and instead lived on Kirkland Street in Cambridge, an area known as Professors’ Row. He stayed there, along with his daughter Mabel and her governess Frances Dunlap, until January 1861. Lowell had intended never to remarry after the death of his wife Maria White. However, in 1857, surprising his friends, he became engaged to Frances Dunlap, who many described as simple and unattractive. Dunlap, niece of the former governor of Maine Robert P. Dunlap, was a friend of Lowell’s first wife and formerly wealthy, though she and her family had fallen into reduced circumstances. Lowell and Dunlap married on September 16, 1857, in a ceremony performed by his brother. Lowell wrote, "My second marriage was the wisest act of my life, & as long as I am sure of it, I can afford to wait till my friends agree with me.” The war years and beyond In the autumn of 1857, The Atlantic Monthly was established, and Lowell was its first editor. With its first issue in November of that year, he at once gave the magazine the stamp of high literature and of bold speech on public affairs. In January 1861, Lowell’s father died of a heart attack, inspiring Lowell to move his family back to Elmwood. As he wrote to his friend Briggs, “I am back again to the place I love best. I am sitting in my old garret, at my old desk, smoking my old pipe... I begin to feel more like my old self than I have these ten years.” Shortly thereafter, in May, he left The Atlantic Monthly when James Thomas Fields took over as editor; the magazine had been purchased by Ticknor and Fields for $10,000 two years before. Lowell returned to Elmwood by January 1861 but maintained an amicable relationship with the new owners of the journal, continuing to submit his poetry and prose for the rest of his life. His prose, however, was more abundantly presented in the pages of the North American Review during the years 1862–1872. For the Review, he served as a coeditor along with Charles Eliot Norton. Lowell’s reviews for the journal covered a wide variety of literary releases of the day, though he was writing fewer poems. As early as 1845, Lowell had predicted the debate over slavery would lead to war and, as the American Civil War broke out in the 1860s, Lowell used his role at the Review to praise Abraham Lincoln and his attempts to maintain the Union. Lowell lost three nephews during the war, including Charles Russell Lowell, Jr, who became a Brigadier General and fell at the battle of Cedar Creek. Lowell himself was generally a pacifist. Even so, he wrote, “If the destruction of slavery is to be a consequence of the war, shall we regret it? If it be needful to the successful prosecution of the war, shall anyone oppose it?” His interest in the Civil War inspired him to write a second series of The Biglow Papers, including one specifically dedicated to the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation called “Sunthin’ in the Pastoral Line” in 1862. Shortly after Lincoln’s assassination, Lowell was asked to present a poem at Harvard in memory of graduates killed in the war. His poem, “Commemoration Ode,” cost him sleep and his appetite, but was delivered on July 21, 1865, after a 48-hour writing binge. Lowell had high hopes for his performance but was overshadowed by the other notables presenting works that day, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. “I did not make the hit I expected,” he wrote, “and am ashamed at having been tempted again to think I could write poetry, a delusion from which I have been tolerably free these dozen years.” Despite his personal assessment, friends and other poets sent many letters to Lowell congratulating him. Emerson referred to his poem’s "high thought & sentiment" and James Freeman Clarke noted its “grandeur of tone.” Lowell later expanded it with a strophe to Lincoln. In the 1860s, Lowell’s friend Longfellow spent several years translating Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy and regularly invited others to help him on Wednesday evenings. Lowell was one of the main members of the so-called “Dante Club,” along with William Dean Howells, Charles Eliot Norton and other occasional guests. Shortly after serving as a pallbearer at the funeral of friend and publisher Nathaniel Parker Willis, on January 24, 1867, Lowell decided to produce another collection of his poetry. Under the Willows and Other Poems was released in 1869, though Lowell originally wanted to title it The Voyage to the Vinland and Other Poems. The book, dedicated to Norton, collected poems Lowell had written within the previous twenty years and was his first poetry collection since 1848. Lowell intended to take another trip to Europe. To finance it, he sold off more of Elmwood’s acres and rented the house to Thomas Bailey Aldrich; Lowell’s daughter Mabel, by this time, had moved into a new home with her husband Edward Burnett, the son of a successful businessman-farmer from Southboro, Massachusetts. Lowell and his wife set sail on July 8, 1872, after he took a leave of absence from Harvard. They visited England, Paris, Switzerland, and Italy. While overseas, he received an honorary Doctorate of Law from the University of Oxford and another from Cambridge University. They returned to the United States in the summer of 1874. Political appointments Lowell resigned from his Harvard professorship in 1874, though he was persuaded to continue teaching through 1877. It was in 1876 that Lowell first stepped into the field of politics. That year, he served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, speaking on behalf of presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes. Hayes won the nomination and, eventually, the presidency. In May 1877, President Hayes, an admirer of The Biglow Papers, sent William Dean Howells to Lowell with a handwritten note proffering an ambassadorship to either Austria or Russia; Lowell declined, but noted his interest in Spanish literature. Lowell was then offered and accepted the role of Minister to the court of Spain at an annual salary of $12,000. Lowell sailed from Boston on July 14, 1877, and, though he expected he would be away for a year or two, he would not return to the United States until 1885, with the violinist Ole Bull renting Elmwood for a portion of that time. The Spanish media referred to him as “José Bighlow.” Lowell was well-prepared for his political role, having been trained in law, as well as being able to read in multiple languages. He had trouble socializing while in Spain, however, and amused himself by sending humorous dispatches to his political bosses in the United States, many of which were later collected and published posthumously in 1899 as Impressions of Spain. Lowell’s social life improved when the Spanish Academy elected him a corresponding member in late 1878, allowing him contribute to the preparation of a new dictionary. In January 1880, Lowell was informed he was appointed Minister to England, his nomination made without his knowledge as far back as June 1879. He was granted a salary of $17,500 with about $3,500 for expenses. While serving in this capacity, he addressed an importation of allegedly diseased cattle and made recommendations that predated the Pure Food and Drug Act. Queen Victoria commented that she had never seen an ambassador who “created so much interest and won so much regard as Mr. Lowell.” Lowell held this role until the close of Chester A. Arthur’s presidency in the spring of 1885, despite his wife’s failing health. Lowell was already well known in England for his writing and, during his time there, he befriended fellow author Henry James, who referred to him as “conspicuously American.” Lowell also befriended Leslie Stephen many years earlier and became the godfather to his daughter, future writer Virginia Woolf. Lowell was popular enough that he was offered a professorship at Oxford after his recall by president Grover Cleveland, though the offer was declined. His second wife, Frances, died on February 19, 1885, while still in England. Later years and death He returned to the United States by June 1885, living with his daughter and her husband in Southboro, Massachusetts. He then spent time in Boston with his sister before returning to Elmwood in November 1889. By this time, most of his friends were dead, including Quincy, Longfellow, Dana, and Emerson, leaving him depressed and contemplating suicide again. Lowell spent part of the 1880s delivering various speeches, and his last published works were mostly collections of essays, including Political Essays, and a collection of his poems Heartsease and Rue in 1888. His last few years he traveled back to England periodically and when he returned to the United States in the fall of 1889, he moved back to Elmwood with Mabel, while her husband worked for clients in New York and New Jersey. That year, Lowell gave an address at the centenary of George Washington’s inauguration. Also that year, the Boston Critic dedicated a special issue to Lowell on his seventieth birthday to recollections and reminiscences by his friends, including former presidents Hayes and Benjamin Harrison and British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone as well as Alfred Tennyson and Francis Parkman. In the last few months of his life, Lowell struggled with gout, sciatica in his left leg, and chronic nausea; by the summer of 1891, doctors believed that Lowell had cancer in his kidneys, liver, and lungs. His last few months, he was administered opium for the pain and was rarely fully conscious. He died on August 12, 1891, at Elmwood. After services in the Appleton Chapel, he was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery. After his death, Norton served as his literary executor and published several collections of Lowell’s works and his letters. Writing style and literary theory Early in his career, James Russell Lowell’s writing was influenced by Swedenborgianism, a Spiritualism-infused form of Christianity founded by Emanuel Swedenborg, causing Frances Longfellow (wife of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) to mention that “he has been long in the habit of seeing spirits.” He composed his poetry rapidly when inspired by an “inner light” but could not write to order. He subscribed to the common nineteenth-century belief that the poet was a prophet but went further, linking religion, nature, and poetry, as well as social reform. Evert Augustus Duyckinck and others welcomed Lowell as part of Young America, a New York-based movement. Though not officially affiliated with them, he shared some of their ideals, including the belief that writers have an inherent insight into the moral nature of humanity and have an obligation for literary action along with their aesthetic function. Unlike many of his contemporaries, including members of Young America, Lowell did not advocate for the creation of a new national literature. Instead, he called for a natural literature, regardless of country, caste, or race, and warned against provincialism which might “put farther off the hope of one great brotherhood.” He agreed with his neighbor Longfellow that “whoever is most universal, is also most national.” As Lowell said: I believe that no poet in this age can write much that is good unless he gives himself up to [the radical] tendency... The proof of poetry is, in my mind, that it reduces to the essence of a single line the vague philosophy which is floating in all men’s minds, and so render it portable and useful, and ready to the hand... At least, no poem ever makes me respect its author which does not in some way convey a truth of philosophy. A scholar of linguistics, Lowell was one of the founders of the American Dialect Society. He used this interest in his writing, particularly in The Biglow Papers, presenting a heavily ungrammatical phonetic spelling of the Yankee dialect. In using this vernacular, Lowell intended to get closer to the common man’s experience and was rebelling against more formal and, as he thought, unnatural representations of Americans in literature. As he wrote in his introduction to The Biglow Papers, “few American writers or speakers wield their native language with the directness, precision, and force that are common as the day in the mother country.” Though intentionally humorous, this accurate presentation of the dialect was pioneering work in American literature. For example, Lowell’s character Hosea Biglow says in verse: Lowell is considered one of the Fireside Poets, a group of writers from New England in the 1840s who all had a substantial national following and whose work was often read aloud by the family fireplace. Besides Lowell, the main figures from this group were Longfellow, Holmes, John Greenleaf Whittier, and William Cullen Bryant. Beliefs Although he was an abolitionist, Lowell’s opinions on African-Americans wavered. Though Lowell advocated suffrage for blacks, he noted that their ability to vote could be troublesome. Even so, he wrote, “We believe the white race, by their intellectual and traditional superiority, will retain sufficient ascendancy to prevent any serious mischief from the new order of things.” Freed slaves, he wrote, were "dirty, lazy & lying." Even before his marriage to the abolitionist Maria White, Lowell wrote: “The abolitionists are the only ones with whom I sympathize of the present extant parties.” After his marriage, Lowell at first did not share White’s enthusiasm for the cause but was eventually pulled in. The couple often gave money to fugitive slaves, even when their own financial situation was not strong, especially if they were asked to free a spouse or child. Even so, he did not always fully agree with the followers of the movement. The majority of these people, he said, “treat ideas as ignorant persons do cherries. They think them unwholesome unless they are swallowed, stones and all.” Lowell depicted Southerners very unfavorably in his second collection of The Biglow Papers but, by 1865, admitted that Southerners were “guilty only of weakness” and, by 1868, said that he sympathized with Southerners and their viewpoint on slavery. Enemies and friends of Lowell alike questioned his vacillating interest in the question of slavery. Abolitionist Samuel Joseph May accused Lowell of trying to quit the movement because of his association with Harvard and the Boston Brahmin culture: “Having got into the smooth, dignified, self-complacent, and change-hating society of the college and its Boston circles, Lowell has gone over to the world, and to 'respectability’.” Lowell was also involved in other reform movements. He urged for better conditions for factory workings, opposed capital punishment, and supported the temperance movement. His friend Longfellow was especially concerned about his fanaticism for temperance, worrying that Lowell would ask him to destroy his wine cellar. There are many references to Lowell’s drinking during his college years and part of his reputation in school was based on it. His friend Edward Everett Hale denied these allegations and, even then, Lowell considered joining the “Anti-Wine” club and later, during the early years of his first marriage, became a teetotaler. However, as Lowell gained notoriety, he became popular in social circles and clubs and, away from his wife, he drank rather heavily. When he drank, he had wild mood swings, ranging from euphoria to frenzy. Criticism and legacy In 1849, Lowell said of himself, “I am the first poet who has endeavored to express the American Idea, and I shall be popular by and by.” Poet Walt Whitman said: “Lowell was not a grower—he was a builder. He built poems: he didn’t put in the seed, and water the seed, and send down his sun—letting the rest take care of itself: he measured his poems—kept them within formula.” Fellow Fireside Poet John Greenleaf Whittier praised Lowell by writing two poems in his honor and calling him “our new Theocritus” and “one of the strongest and manliest of our writers–a republican poet who dares to speak brave words of unpopular truth.” British author Thomas Hughes referred to Lowell as one of the most important writers in the United States: "Greece had her Aristophanes; Rome her Juvenal; Spain has had her Cervantes; France her Rabelais, her Molière, her Voltaire; Germany her Jean Paul, her Heine; England her Swift, her Thackeray; and America has her Lowell." Lowell’s satires and use of dialect were an inspiration for writers like Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, H. L. Mencken, and Ring Lardner. Contemporary critic and editor Margaret Fuller wrote, “his verse is stereotyped; his thought sounds no depth, and posterity will not remember him.” Duyckinck thought Lowell was too similar to other poets like William Shakespeare and John Milton. Ralph Waldo Emerson noted that, though Lowell had significant technical skill, his poetry “rather expresses his wish, his ambition, than the uncontrollable interior impulse which is the authentic mark of a new poem... and which is felt in the pervading tone, rather than in brilliant parts or lines.” Even his friend Richard Henry Dana Jr., questioned Lowell’s abilities, calling him "very clever, entertaining & good humored... but he is rather a trifler, after all." In the twentieth century, poet Richard Armour dismissed Lowell, writing: “As a Harvard graduate and an editor for the Atlantic Monthly, it must have been difficult for Lowell to write like an illiterate oaf, but he succeeded.” The poet Amy Lowell featured her relative James Russell Lowell in her poem A Critical Fable (1922), the title mocking A Fable for Critics. Here, a fictional version of Lowell says he does not believe that women will ever be equal to men in the arts and “the two sexes cannot be ranked counterparts.” Modern literary critic Van Wyck Brooks wrote that Lowell’s poetry was forgettable: “one read them five times over and still forgot them, as if this excellent verse had been written in water.” Nonetheless, in 1969 the Modern Language Association established a prize named after Lowell, awarded annually for “an outstanding literary or linguistic study, a critical edition of an important work, or a critical biography.” Lowell’s poem “The Present Crisis,” an early work that addressed the national crisis over slavery leading up to the Civil War, has had an impact in the modern civil rights movement. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People named its newsletter The Crisis after the poem, and Martin Luther King, Jr. frequently quoted the poem in his speeches and sermons. The poem was also the source of the hymn Once to Every Man and Nation. List of selected works Poetry collections * A Year’s Life (1841) * Miscellaneous Poems (1843) * The Biglow Papers (1848) * A Fable for Critics (1848) * Poems (1848) * The Vision of Sir Launfal (1848) * Under the Willows (1869) * The Cathedral (1870) * Heartsease and Rue (1888) Essay collections * Conversations on the Old Poets (1844) * Fireside Travels (1864) * Among My Books (1870) * My Study Windows (1871) * Among My Books (second collection, 1876) * Democracy and Other Addresses (1886) * Political Essays (1888) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Russell_Lowell

Amy Judith Levy (10 November 1861– 10 September 1889) was a British essayist, poet, and novelist best remembered for her literary gifts; her experience as the first Jewish woman at Cambridge University and as a pioneering woman student at Newnham College, Cambridge; her feminist positions; her friendships with others living what came later to be called a “new woman” life, some of whom were lesbians; and her relationships with both women and men in literary and politically activist circles in London during the 1880s. Biography Levy was born in Clapham, an affluent district of London, on November 10, 1861, to Lewis and Isobel Levy. She was the second of seven children born into a Jewish family with a “casual attitude toward religious observance” who sometimes attended a Reform synagogue in Upper Berkeley Street. As an adult, Levy continued to identify herself as Jewish and wrote for The Jewish Chronicle. Levy showed interest in literature from an early age. At 13, she wrote a criticism of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s feminist work Aurora Leigh; at 14, Levy’s first poem, “Ida Grey: A Story of Woman’s Sacrifice”, was published in the journal Pelican. Her family was supportive of women’s education and encouraged Amy’s literary interests; in 1876, she was sent to Brighton and Hove High School and later studied at Newnham College, Cambridge. Levy was the first Jewish student at Newnham when she arrived in 1879 but left before her final year without taking her exams. Her circle of friends included Clementina Black, Dollie Radford, Eleanor Marx (daughter of Karl Marx), and Olive Schreiner. While travelling in Florence in 1886, Levy met Vernon Lee, a fiction writer and literary theorist six years her senior, and fell in love with her. Both women would go on to write works with themes of sapphic love. Lee inspired Levy’s poem “To Vernon Lee.” Literary career The Romance of a Shop (1888), Levy’s first novel, is regarded as an early “New Woman” novel and depicts four sisters who experience the difficulties and opportunities afforded to women running a business in 1880s London, Levy wrote her second novel, Reuben Sachs (1888), to fill the literary need for “serious treatment... of the complex problem of Jewish life and Jewish character”, which she identified and discussed in her 1886 article “The Jew in Fiction.” Levy wrote stories, essays, and poems for popular or literary periodicals; the stories “Cohen of Trinity” and “Wise in Their Generation”, both published in Oscar Wilde’s magazine The Woman’s World, are among her most notable. In 1886, Levy began writing a series of essays on Jewish culture and literature for The Jewish Chronicle, including The Ghetto at Florence, The Jew in Fiction, Jewish Humour, and Jewish Children. Levy’s works of poetry, including the daring A Ballad of Religion and Marriage, reveal her feminist concerns. Xantippe and Other Verses (1881) includes “Xantippe”, a poem in the voice of Socrates’s wife; the volume A Minor Poet and Other Verse (1884) includes more dramatic monologues as well as lyric poems. Her final book of poems, A London Plane-Tree (1889), contains lyrics that are among the first to show the influence of French symbolism. Suicide Levy suffered from episodes of major depression from an early age. In her later years, her depression worsened in connection to her distress surrounding her romantic relationships and her awareness of her growing deafness. Two months away from her 28th birthday, she committed suicide at the residence of her parents... [at] Endsleigh Gardens by inhaling carbon monoxide. Oscar Wilde wrote an obituary for her in Women’s World in which he praised her gifts.

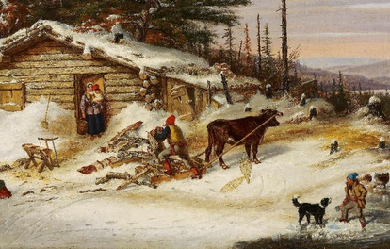

Archibald Lampman FRSC (17 November 1861– 10 February 1899) was a Canadian poet. “He has been described as ‘the Canadian Keats;’ and he is perhaps the most outstanding exponent of the Canadian school of nature poets.” The Canadian Encyclopedia says that he is "generally considered the finest of Canada’s late 19th-century poets in English.” Lampman is classed as one of Canada’s Confederation Poets, a group which also includes Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, and Duncan Campbell Scott. Life Archibald Lampman was born at Morpeth, Ontario, a village near Chatham, the son of Archibald Lampman, an Anglican clergyman. “The Morpeth that Lampman knew was a small town set in the rolling farm country of what is now western Ontario, not far from the shores of Lake Erie. The little red church just east of the town, on the Talbot Road, was his father’s charge.” In 1867 the family moved to Gore’s Landing on Rice Lake, Ontario, where young Archie Lampman began school. In 1868 he contracted rheumatic fever, which left him lame for some years and with a permanently weakened heart. Lampman attended Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario, and then Trinity College in Toronto, Ontario (now part of the University of Toronto), graduating in 1882. While at university, he published early poems in Acta Victoriana, the literary journal of Victoria College. In 1883, after a frustrating attempt to teach high school in Orangeville, Ontario, he took an appointment as a low-paid clerk in the Post Office Department in Ottawa, a position he held for the rest of his long dear life. Lampman “was slight of form and of middle height. He was quiet and undemonstrative in manner, but had a fascinating personality. Sincerity and high ideals characterized his life and work.” On Sep. 3, 1887, Lampman married 20-year-old Maude Emma Playter. "They had a daughter, Natalie Charlotte, born in 1892. Arnold Gesner, born May 1894, was the first boy, but he died in August. A third child, Archibald Otto, was born in 1898." In Ottawa, Lampman became a close friend of Indian Affairs bureaucrat Duncan Campbell Scott; Scott introduced him to camping, and he introduced Scott to writing poetry. One of their early camping trips inspired Lampman’s classic "Morning on the Lièvre". Lampman also met and befriended poet William Wilfred Campbell. Lampman, Campbell, and Scott together wrote a literary column, “At the Mermaid Inn,” for the Toronto Globe from February 1892 until July 1893. (The name was a reference to the Elizabethan-era Mermaid Tavern.) As Lampman wrote to a friend: Campbell is deplorably poor.... Partly in order to help his pockets a little Mr. Scott and I decided to see if we could get the Toronto “Globe” to give us space for a couple of columns of paragraphs & short articles, at whatever pay we could get for them. They agreed to it; and Campbell, Scott and I have been carrying on the thing for several weeks now. “In the last years of his short life there is evidence of a spiritual malaise which was compounded by the death of an infant son [Arnold, commemorated in the poem “White Pansies”] and his own deteriorating health." Lampman died in Ottawa at the age of 37 due to a weak heart, an after-effect of his childhood rheumatic fever. He is buried, fittingly, at Beechwood Cemetery, in Ottawa, a site he wrote about in the poem “In Beechwood Cemetery” (which is inscribed at the cemetery’s entranceway). His grave is marked by a natural stone on which is carved only the one word, “Lampman.”. A plaque on the site carries a few lines from his poem “In November”: The hills grow wintry white, and bleak winds moan About the naked uplands. I alone Am neither sad, nor shelterless, nor gray Wrapped round with thought, content to watch and dream. Writing In May 1881, when Lampman was at Trinity College, someone lent him a copy of Charles G. D. Roberts’s recently published first book, Orion and Other Poems. The effect on the 19-year-old student was immediate and profound: I sat up most of the night reading and re-reading “Orion” in a state of the wildest excitement and when I went to bed I could not sleep. It seemed to me a wonderful thing that such work could be done by a Canadian, by a young man, one of ourselves. It was like a voice from some new paradise of art, calling to us to be up and doing. A little after sunrise I got up and went out into the college grounds... everything was transfigured for me beyond description, bathed in an old world radiance of beauty; the magic of the lines was sounding in my ears, those divine verses, as they seemed to me, with their Tennyson-like richness and strange earth-loving Greekish flavour. I have never forgotten that morning, and its influence has always remained with me. Lampman sent Roberts a fan letter, which "initiated a correspondence between the two young men, but they probably did not meet until after Roberts moved to Toronto in late September 1883 to become the editor of Goldwin Smith’s The Week.” Inspired, Lampman also began writing poetry, and soon after began publishing it: first “in the pages of his college magazine, Rouge et Noir;” then “graduating to the more presitigious pages of The Week”– (his sonnet “A Monition,” later retitled “The Coming of Winter,” appeared in its first issue )– and finally, by the late 1880s “winning an audience in the major magazines of the day, such as Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and Scribner’s.” Lampman published mainly nature poetry in the current late-Romantic style. “The prime literary antecedents of Lampman lie in the work of the English poets Keats, Wordsworth, and Arnold,” says the Gale Encyclopedia of Biography, “but he also brought new and distinctively Canadian elements to the tradition. Lampman, like others of his school, relied on the Canadian landscape to provide him with much of the imagery, stimulus, and philosophy which characterize his work.... Acutely observant in his method, Lampman created out of the minutiae of nature careful compositions of color, sound, and subtle movement. Evocatively rich, his poems are frequently sustained by a mood of revery and withdrawal, while their themes are those of beauty, wisdom, and reassurance, which the poet discovered in his contemplation of the changing seasons and the harmony of the countryside.” The Canadian Encyclopedia calls his poems “for the most part close-packed melancholy meditations on natural objects, emphasizing the calm of country life in contrast to the restlessness of city living. Limited in range, they are nonetheless remarkable for descriptive precision and emotional restraint. Although characterized by a skilful control of rhythm and sound, they tend to display a sameness of thought.” “Lampman wrote more than 300 poems in this last period of his life, although scarcely half of these were published prior to his death. For single poems or groups of poems he found outlets in the literary magazines of the day: in Canada, chiefly the Week; in the United States, Scribner’s Magazine, The Youth’s Companion, the Independent, the Atlantic Monthly, and Harper’s Magazine. In 1888, with the help of a legacy left to his wife, he published Among the millet and other poems," his first book, at his own expense. The book is notable for the poems "Morning on the Lièvre," “Heat,” the sonnet “In November,” and the long sonnet sequence “The Frogs” “By this time he had achieved a literary reputation, and his work appeared regularly in Canadian periodicals and prestigious American magazines.... In 1895 Lampman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and his second collection of poems, Lyrics of Earth, was brought out by a Boston publisher.” The book was not a success. “The sales of Lyrics of Earth were disappointing and the only critical notices were four brief though favourable reviews. In size, the volume is slighter than Among the Millet—twenty-nine poems in contrast to forty-eight—and in quality fails to surpass the earlier work.” (Lyrics does, though, contain some of Lampman’s most beautiful poems, such as “After Rain” and “The Sun Cup.”) “A third volume, Alcyone and other poems, in press at the time of his death” in 1899, showed Lampman starting to move in new directions, with the nature verses interspersed with philosophical poetry like “Voices of Earth” and “The Clearer Self” and poems of social criticism like “The City” and what may be his best-known poem, the dystopian vision of “The City of the End of Things.” “As a corollary to his preoccupation with nature,” notes the Gale Encyclopedia, "Lampman [had] developed a critical stance toward an emerging urban civilization and a social order against which he pitted his own idealism. He was an outspoken socialist, a feminist, and a social critic." Canadian critic Malcolm Ross wrote that “in poems like 'The City at the End of Things’ and 'Epitaph on a Rich Man’ Lampman seems to have a social and political insight absent in his fellows.” However, Lampman died before Alcyone appeared, and it "was held back by Scott (12 specimen copies were printed posthumously in Ottawa in 1899) in favour of a comprehensive memorial volume planned for 1900." The latter was a planned collected poems "which he was editing in the hope that its sale would provide Maud with some much-needed cash. Besides Alcyone, it included Among the Millet and Lyrics of Earth in their entirety, plus seventy-four sonnets Lampman had tried to publish separately, twenty-three miscellaneous poems and ballads, and two long narrative poems (“David and Abigail” and “The Story of an Affinity”)." Among the previously unpublished sonnets were some of Lampman’s finest work, including “Winter Uplands”, “The Railway Station,” and “A Sunset at Les Eboulements.” “Published by Morang & Company of Toronto in 1900," The Poems of Archibald Lampman "was a substantial tome—473 pages—and ran through several editions. Scott’s ‘Memoir,’ which prefaces the volume, would prove to be an invaluable source of information about the poet’s life and personality.” Scott published one further volume of Lampman’s poetry, At the Long Sault and Other Poems, in 1943– “and on this occasion, as on other occasions previously, he did not hesitate to make what he felt were improvements on the manuscript versions of the poems.” The book is remarkable mainly for its title poem, "At the Long Sault: May 1660," a dramatic retelling of the Battle of Long Sault, which belongs with the great Canadian historical poems. It was co-edited by E.K. Brown, who the same year published his own volume On Canadian Poetry: a book that was a major boost to Lampman’s reputation. Brown considered Lampman and Scott the top Confederation Poets, well ahead of Roberts and Carman, and his view came to predominate over the next few decades. Lampman never considered himself more than a minor poet, as he once confessed in a letter to a friend: “I am not a great poet and I never was. Greatness in poetry must proceed from greatness of character—from force, fearlessness, brightness. I have none of those qualities. I am, if anything, the very opposite, I am weak, I am a coward, I am a hypochondriac. I am a minor poet of a superior order, and that is all.” However, others’ opinion of his work has been higher than his own. Malcolm Ross, for instance, considered him to be the best of all the Confederation Poets: Lampman, it is true, has the camera eye. But Lampman is no mere photographer. With Scott (and more completely than Scott), he has, poetically, met the demands of his place and his time.... Like Roberts (and more intensively than Roberts), he searches for the idea.... Ideas are germinal for him, infecting the tissue of his thought.... Like the existentialist of our day, Lampman is not so much 'in search of himself’ as engaged strenuously in the creation of the self. Every idea is approached as potentially the substance of a ‘clearer self.’ Even landscape is made into a symbol of the deep, interior processes of the self, or is used... to induce a settling of the troubled surfaces of the mind and a miraculous transparency that opens into the depths. Recognition Lampman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1895. He was designated a Person of National Historic Significance in 1920. A literary prize, the Archibald Lampman Award, is awarded annually by Ottawa-area poetry magazine Arc in Lampman’s honour. Since 1999, the annual “Archibald Lampman Poetry Reading” has brought leading Canadian poets to Trinity College, Toronto, under the sponsorship of the John W. Graham Library and the Friends of the Library, Trinity College. His name is also carried on in the town of Lampman, Saskatchewan, a small community of approximately 730 people, situated near the City of Estevan. Canada Post issued a postage stamp in his honour on July 7, 1989. The stamp depicts Lampman’s portrait on a backdrop of nature. Canadian singer/songwriter Loreena McKennitt adapted Lampman’s poem “Snow” as a song, writing original music while keeping as the lyrics the poem verbatim. This adaptation appears on McKennitt’s album To Drive the Cold Winter Away (1987) and also in a different version on her EP, A Winter Garden: Five Songs for the Season (1995). Publications Poetry * Lampman, Archibald (1888). Among the Millett, and Other Poems. Ottawa, Ontario: J. Durie and son. * Lampman, Archibald (1895). Lyrics of Earth. Boston, Massachusetts: Copeland & Day. * Lampman, Archibald; Scott, Duncan Campbell (1896). “Two poems”. privately issued to their friends at Christmastide: not published. * Lampman, Archibald (1899). Alcyone and Other Poems. Ottawa, Ontario: Ogilvy. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1900). The Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto, Ontario: Morang. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1925). Lyrics of Earth: Sonnets and Ballads. Toronto, Ontario: Musson. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1943). At the Long Sault and Other New Poems. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1947). Selected Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. * Coulby Whitridge, Margaret, ed. (1975). Lampman’s Kate: Late Love Poems of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Borealis. ISBN 978-0-9195-9436-4. * Coulby Whitridge, Margaret, ed. (1976). Lampman’s Sonnets: The Complete Sonnets of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Borealis. ISBN 978-0-919594-50-0. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1986). The Story of an Affinity. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. ISBN 978-0-921243-00-7. * Gnarowski, Michael, ed. (1990). Selected Poetry of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-919662-15-5. Prose * Bourinot, Arthur S., ed. (1956). Archibald Lampman’s letters to Edward William Thomson (1890-1898). Ottawa, Ontario: Arthur S. Bourinot Publisher. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1975). Archibald Lampman: Selected Prose. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6254-4. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1979). At the Mermaid Inn: Wilfred Campbell, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott in the Globe 1892–93. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2299-5. * Lynn, Helen, ed. (1980). An annotated edition of the correspondence between Archibald Lampman and Edward William Thomson, 1890-1898. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-919662-77-3. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1996). The Essays and Reviews of Archibald Lampman. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1999). The Fairy Tales of Archibald Lampman. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archibald_Lampman

Alexandre is a musician, poet, and philosopher with a deep interest in the mystical, magickal, and occult. While he has been playing music ever since he was 3 years old, his interest in mysticism and poetry came about from the study of philosophy. Beginning in college with the standard western philosophers such as Plato, Kant, Descartes, and Nietzsche, he realized that there was still much more in the realm of wisdom to be explored. Reading about Zen, Taoism, and Cabala instilled an appreciation of simple, poetic verse as a way of communicating wisdom, and led him to the study of the magickal system of Aleister Crowley, known as Thelema, from where he draws much of his inspiration.

Rafael de León y Arias de Saavedra, también conocido como Maestro León, Conde de Gómara, Marqués del Moscoso y Marqués del Valle de la Reina (Sevilla, 6 de febrero de 1908 – Madrid, 9 de diciembre de 1982), escritor y poeta español de la Generación del 27, autor de letras para copla, formando parte del trío de autores Quintero, León y Quiroga. Rafael nace en el seno de una familia de la nobleza de Sevilla. Durante su juventud frecuenta cafés cantantes y teatros de variedades de la capital andaluza y en esos medios vive un ambiente liberal y permisivo que concedía el nuevo Régimen Republicano, allí fue donde conoció y colaboró con el letrista Antonio García Padilla, alias "Kola", padre de la actriz y cantante Carmen Sevilla, y de aquella relación surgieron ya algunas canciones conocidas. Como letrista, "Kola" no llegaba a la depurada calidad de Rafael de León; pero aceptó de buen grado ser colaborador en parte par facilitarle la entrada al mundo de la creación artística, reacio a los aristócratas. Parecida situación a lo que le ocurrió a Antonio Quintero, Xandro Valerio y José Antonio Ochaíta; todos co-autores de muchas letras de canciones y algunas poesías con Rafael de León. También firmó canciones con Salvador Valverde, poeta porteño de origen andaluz. Durante su servicio militar en Sevilla, conoce a Concha Piquer cuando actuaba en el Teatro Lope de Vega. Esta conocida canzonetista de la canción española, puso voz a muchas de sus mejores creaciones de letras para la canción. En 1932, Rafael de León se traslada a Madrid bajo la influencia del gran músico sevillano Manuel Quiroga, que junto con el autor teatral Antonio Quintero, llegaría a formar el prolífico trío Quintero, León y Quiroga con el que tienen registradas más de cinco mil canciones. Al producirse la guerra civil española, Rafael de León se encontraba en Barcelona; allí es encarcelado, como tantos otros del mundo de la farándula, toreros, cantantes, etc. acusado de monárquico o derechista, por parte de las autoridades republicanas. En la cárcel declarará tener una buena amistad con destacados poetas republicanos como León Felipe; Federico García Lorca y Antonio Machado. Llegan luego los años de posguerra en los que Rafael de León continúa relacionándose con el universo de las varietés, que alimentado por el nuevo ambiente político-cultural instalado ahora, en un inicial entorno hostil de bloqueo internacional, favorece la creación de un género muy influido por el tipismo andaluz y que se ha dado en llamar "folklore español". El nuevo régimen acogió bien este género que ensalzaba con buen gusto y calidad artística todo lo español. Es en dicho periodo cuando este poeta-letrista empieza a colaborar en los guiones de una cinematografía mediocre e impregnada de un realzamiento de lo español que tanto gustaba en la España oficial. En aquella época también, bajo la influencia del concepto 'hispanidad', se abrieron las fronteras españolas a las músicas que venían de los países hermanos de América. Y así llegaron los boleros y los tangos, muy bien acompañados de los valses peruanos, los sones cubanos y las rancheras y corridos mexicanos, que engancharon con facilidad en los gustos musicales españoles de entonces, por tratarse de una cultura común. Así se vivió durante dos décadas, pero, partir de los años sesenta, comienza en España cierto aperturismo cultural y muchos jóvenes empiezan a despreciar, con alguna injusticia, casi toda la música española e hispanoamericana y con ella el conocido estilo de la copla y de la canción andaluza que tan bien había representado el sello "Quintero, León y Quiroga". Rafael de León pertenece por derecho propio a la denominada Generación del 27 de los poetas españoles, aunque un incomprensible olvido ha hecho que nunca figure en esa nómina. De ningún poeta español de este siglo que acaba, han sido tan recitadas sus poesías y tan cantadas las letras de sus canciones, pero sigue siendo el gran ausente al hacer recuento del ámbito de la cultura popular española de nuestra posguerra. La obra poética de Rafael de León, queda dividida en esos dos grandes apartados: poesía propiamente dicha y letras para canciones. En muchos casos unas y otras tienen un inconfundible parentesco por derivar, alimentarse o inspirarse las unas de las otras. En casi toda su obra, inspirada en ambientes muy típicos de Andalucía, queda reflejado el gracejo popular andaluz, indicado por las palabras en cursiva, para mejor entender que no pertenecen al correcto lenguaje español. Su primer libro de poesías Pena y alegría del amor aparece publicado en 1941. Un segundo libro titulado Jardín de papel aparece el año 1943. Del mismo año se relata que aparece editado en Chile un tercer libro titulado Amor de cuando en cuando, pero al no tener certeza en España de su autenticidad, hay quien sospecha que se trata de una de tantas ediciones piratas que ha sufrido la obra de Rafael de León. Hacia el final de su dilatada carrera de letrista, escribió para los cantantes Nino Bravo, Raphael, Rocío Dúrcal, Rocío Jurado o Isabel Pantoja; canciones escritas por él fueron presentadas en el afamado Festival de la Canción de Benidorm, obteniendo el primer premio en la 3ª edición (año 1961) la canción titulada "Enamorada", con letra de Rafael de León y música de Augusto Algueró. Además, el premio a la mejor letra se lo llevó la canción "Quisiera" escrita también por él. En el año anterior, en el II Festival de la Canción de Benidorm, ya obtuvo el 4º premio la canción "Luna de Benidorm" con letra de Rafael de León y música de García Gasca. Y posteriormente, en el año 1971 (XIII edición del famoso festival), la cantante 'Gloria' interpretó la canción "Yo no sé por qué" con letra de Rafael de León y música de Jesús Gluck, aunque esta vez no obtuvo ningún premio. Colaboraciones De las colaboraciones del poeta a la hora de firmar su obras hemos de reseñar lo siguiente: En colaboración con Antonio Quintero, las poesías Profecía; Romance de la serrana loca y miles de letras de canciones que haría inacabable esta biografía. En colaboración con Antonio García Padilla Kola, las letras de las canciones: "Coplas"; "Arturo"; "Cinelandia"; "Cine sonoro"; "La Rajadesa"; "La deseada"; "Manolo Reyes"; "Siempre Sevilla";... En colaboración con Salvador Valverde, el cuplé "Bajo los puentes del Sena" escrito para ser estrenado por la cupletista Raquel Meyer; y las también populares "¡Ay, Maricruz!"; "María de la O"; "Triniá"; y la inolvidable "Ojos Verdes"; entre otras. En colaboración con José Antonio Ochaíta, la letra de la conocida canción: "Eugenia de Montijo"; y algunas pocas más. En colaboración con el poeta Xandro Valerio, las letras de las reconocidas coplas: "Tatuaje" y "La Parrala”. De su dilatada vida de letrista, casi todas sus creaciones fueron musicadas por el prolífico compositor Manuel Quiroga, pero otras letras fueron musicadas por Juan Solano, Augusto Algueró y Manuel Alejandro. Referencias Wikipedia—http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rafael_de_León

I write poetry when I'm in a bad mood, or when I'm depressed. Which is often. I play clarinet, cello, and guitar, and I'm a singer. Sprint cars and rock stars. Classic rock, heavy metal and pop punk fan. Journey and Bon Jovi are life. Green Day saved me. Working on poetry now. Will post when completed.

Il conte Giacomo Leopardi (al battesimo Giacomo Taldegardo Francesco di Sales Saverio Pietro Leopardi; Recanati, 29 giugno 1798 – Napoli, 14 giugno 1837) è stato un poeta, filosofo, scrittore, filologo e glottologo italiano. È ritenuto il maggior poeta dell’Ottocento italiano e una delle più importanti figure della letteratura mondiale, nonché una delle principali del romanticismo letterario; la profondità della sua riflessione sull’esistenza e sulla condizione umana – di ispirazione sensista e materialista – ne fa anche un filosofo di spessore. La straordinaria qualità lirica della sua poesia lo ha reso un protagonista centrale nel panorama letterario e culturale europeo e internazionale, con ricadute che vanno molto oltre la sua epoca. «Questo io conosco e sento, Che degli eterni giri, Che dell'esser mio frale, Qualche bene o contento Avrà fors'altri; a me la vita è male»

Alphonse de Lamartine, de son nom complet Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine, né à Mâcon le 21 octobre 1790 et mort à Paris le 28 février 1869 est un poète, romancier, dramaturge français, ainsi qu’une personnalité politique qui participa à la Révolution de février 1848 et proclama la Deuxième République. Il est l’une des grandes figures du romantisme en France.

Denise Levertov (24 October 1923– 20 December 1997) was a British-born American poet. Levertov, who was educated at home, showed an enthusiasm for writing from an early age and studied ballet, art, piano and French as well as standard subjects. She wrote about the strangeness she felt growing up part Jewish, German, Welsh and English, but not fully belonging to any of these identities. She notes that it lent her a sense of being special rather than excluded: “I knew before I was ten that I was an artist-person and I had a destiny”.