Alan Seeger (22 June 1888– 4 July 1916) was an American poet who fought and died in World War I during the Battle of the Somme serving in the French Foreign Legion. Seeger was the uncle of American folk singer Pete Seeger, and was a classmate of T.S. Eliot at Harvard. He is most well known for having authored the poem, I Have a Rendezvous with Death, a favorite of President John F. Kennedy. A statue modeled after Seeger is found on the monument honoring fallen Americans who volunteered for France during the war, located at the Place des États-Unis, Paris. He is sometimes called the “American Rupert Brooke.” Early life Born in New York on June 22, 1888, Seeger moved with his family to Staten Island at the age of one and remained there until the age of 10. In 1900, his family moved to Mexico for two years, which influenced the imagery of some of his poetry. His brother Charles Seeger, a noted pacifist and musicologist, was the father of the American folk singers Peter “Pete” Seeger, Mike Seeger, and Margaret “Peggy” Seeger. Seeger entered Harvard in 1906 after attending several elite preparatory schools, including Hackley School. Writing At Harvard, he edited and wrote for the Harvard Monthly. Among his friends there (and afterward) was the American Communist John Reed, though the two had differing ideological views, and his Harvard class also included T.S. Eliot and Walter Lippmann, among others. After graduating in 1910, he moved to Greenwich Village for two years, where he wrote poetry and enjoyed the life of a young bohemian. During his time in Greenwich Village, he attended soirées at the Mlles. Petitpas’ boardinghouse (319 West 29th Street), where the presiding genius was the artist and sage John Butler Yeats, father of the poet William Butler Yeats. Having moved to the Latin Quarter of Paris to continue his seemingly itinerant intellectual lifestyle, on August 24, 1914, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion so that he could fight for the Allies in World War I (the United States did not enter the war until 1917). Death He was killed in action at Belloy-en-Santerre on July 4, 1916, famously cheering on his fellow soldiers in a successful charge after being hit several times by machine gun fire. Poetry Seeger’s poetry was published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in December 1916 with a 46-page introduction by William Archer. Poems, a collection of his works, was relatively unsuccessful, due, according to Eric Homberger, to its lofty idealism and language, qualities out of fashion in the early decades of the 20th century. Poems was reviewed in The Egoist, where the critic—T. S. Eliot, Seeger’s classmate at Harvard—commented that, Seeger was serious about his work and spent pains over it. The work is well done, and so much out of date as to be almost a positive quality. It is high-flown, heavily decorated and solemn, but its solemnity is thorough going, not a mere literary formality. Alan Seeger, as one who knew him can attest, lived his whole life on this plane, with impeccable poetic dignity; everything about him was in keeping. One of his more famous poems was I Have a Rendezvous with Death, published posthumously. A recurrent theme in both his poetic works and his personal writings was his desire for his life to end gloriously at an early age. This particular poem, according to the JFK Library, “was one of John F. Kennedy’s favorite poems and he often asked his wife (Jacqueline) to recite it.” Memorials On 4 July 1923, the President of the French Council of State, Raymond Poincaré, dedicated a monument in the Place des États-Unis to the Americans who had volunteered to fight in World War I in the service of France. The monument, in the form of a bronze statue on a plinth, executed by Jean Boucher, had been financed through a public subscription. Boucher had used a photograph of Seeger as his inspiration, and Seeger’s name can be found, among those of 23 others who had fallen in the ranks of the French Foreign Legion, on the back of the plinth. Also, on either side of the base of the statue, are two excerpts from Seeger’s “Ode in Memory of the American Volunteers Fallen for France”, a poem written shortly before his death on 4 July 1916. Seeger intended that his words should be read in Paris on 30 May of that year, at an observance of the American holiday, Decoration Day (later known as Memorial Day): They did not pursue worldly rewards; they wanted nothing more than to live without regret, brothers pledged to the honor implicit in living one’s own life and dying one’s own death. Hail, brothers! Goodbye to you, the exalted dead! To you, we owe two debts of gratitude forever: the glory of having died for France, and the homage due to you in our memories. Alan Seeger Natural Area, in central Pennsylvania, was named by Colonel Henry Shoemaker. It is unknown if Alan Seeger had any connection to the area or why Shoemaker chose to memorialize the poet. The area is known for its virgin trees. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Seeger

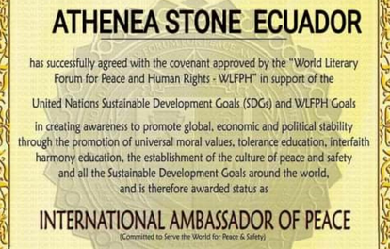

Nací el 12 de diciembre de 2006 en Puerto Rico, La isla del Encanto. 🏝 🇵🇷 (Actualmente 17 años) Mi pasión es la lectura, el canto, el dibujo, los instrumentos musicales, los animales y la poesía... Mi amor por la lectura comenzó desde que leí la Biblia por primera vez. Cada palabra desbordada de verdad dirigió cada una de mis sendas y mi vida se llenó de verdadero propósito. Más tarde, comencé a escribir poesías, irónicamente sin saber que era una poesía. Al cabo de un año, aprendí más a fondo de lo que se trataba la poesía. Actualmente, no he podido parar de escribir y es uno de los amores de mi vida. Para mí, la poesía es la hermosa vestidura del alma de aquellas personas que buscan derramar sus más sinceros sentimientos. Así como las telas cubren nuestro cuerpo, las poesías con sus cálidos mantos cubren nuestro ser, alivian nuestro dolor y avivan nuestra pasión. ❤️🔥 "Que sus palabras sean siempre agradables, sazonadas con sal, para que sepan cómo deben responder a cada persona." (Colosenses 4:6)

Kenneth Adolf Slessor OBE (27 March 1901– 30 June 1971) was an Australian poet, journalist and official War Correspondent in World War II. He was one of Australia’s leading poets, notable particularly for the absorption of modernist influences into Australian poetry. The Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry is named after him. Early life Slessor was born Kenneth Adolphe Schloesser in Orange, New South Wales. As a boy, he lived in England for a time with his parents and in Australia visited the mines of rural New South Wales with his father, a Jewish mining engineer whose father and grandfather had been distinguished musicians in Germany. His family moved to Sydney in 1903. Slessor attended Mowbray House School (1910–1914) and the Sydney Church of England Grammar School (1915–1918), where he began to write poetry. His first published poem was in 1917 about a digger in Europe, remembering Sydney and its icons. Slessor passed the 1918 NSW Leaving Certificate with first-class honours in English and joined the Sydney Sun as a journalist. In 1919, seven of his poems were published. He married for the first time in 1922. Career Slessor made his living as a newspaper journalist, mostly for the Sydney Sun, and was a war correspondent during World War II (1939–1945). Slessor counted Norman Lindsay, Hugh McCrae and Jack Lindsay among his friends. As the Australian Official War Correspondent during World War II, Slessor reported not only from Australia but from Greece, Syria, Libya, Egypt, and New Guinea. Slessor also wrote on rugby league football for the popular publication Smith’s Weekly. Poetry The bulk of Slessor’s poetic work was produced before the end of the Second World War. His poem “Five Bells”—relating to Sydney Harbour, time, the past, memory, and the death of the artist, friend and colleague of Slessor at Smith’s Weekly, Joe Lynch—remains probably his best known poem, followed by “Beach Burial”, a tribute to Australian troops who fought in World War II. In 1965, Australian writer Hal Porter wrote of having met and stayed with Slessor in the 1930s. He described Slessor as: ...a city lover, fastidious and excessively courteous, in those qualities resembles Baudelaire, as he does in being incapable of sentimentalizing over vegetation, in finding in nature something cruel, something bordering on effrontery. He prefers chiselled stone to the disorganization of grass. Awards In the New Year’s Honours of 1959, Slessor was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to literature. Personal life At the age of 21, Slessor married 28-year-old Noëla Glasson in Ashfield, Sydney, on 18 August 1922. Noëla died of cancer on 22 October 1945. He married Pauline Wallace in 1951; and a year later celebrated the birth of his only child, Paul Slessor, before the marriage dissolved in 1961. Death He died alone and suddenly of a heart attack on 30 June 1971 at the Mater Misericordiae Hospital, North Sydney. Bibliography Poetry collections * Thief of the Moon, Sydney: Hand press of J. T. Kirtley (1924) * Earth-Visitors, London: Fanfrolico Press (1926) * Trio: a book of poems, with Harley Matthews and Colin Simpson, Sydney: Sunnybrook Press (1931) * Cuckooz Contrey, Sydney: Frank Johnson (1932) * Darlinghurst Nights: and Morning glories: being 47 strange sights, Sydney (1933) * Funny Farmyard: Nursery Rhymes and Painting Book, with drawings by Sydney Miller, Sydney: Frank Johnson (1933) * Five Bells: XX Poems, Sydney: F.C. Johnson (1939) * One Hundred Poems, 1919–1939, Sydney: Angus & Robertson (1944) * “Beach Burial” 1944 * “The Night Ride” * “Sleep” * “Out of Time” 1930 Essays/prose * Bread and Wine, Sydney, Angus & Robertson (1970) Edited * Australian Poetry (1945) * The Penguin Book of Modern Australian Verse (Melbourne, 1961) Recognition Slessor has a street in the Canberra suburb of McKellar named after him. The bells motif in “Five Bells” is referenced at the end of the 1999 song “You Gotta Love This City” by The Whitlams, which also involves a drowning death in Sydney Harbour. Slessor’s poetry was chosen to be placed on the Higher School Certificate English reading lists, and was also examined in the final English exam. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenneth_Slessor

James Brunton Stephens (17 June 1835– 29 June 1902) was a Scottish-born Australian poet, author of Convict Once. Born at Borrowstounness, on the Firth of Forth, Scotland; the son of John Stephens, the parish schoolmaster, and his wife Jane, née Brunton. J. B. Stephens was educated at his father’s school, then at a free boarding school and at the University of Edinburgh from 1849 to 1854 without obtaining a degree. For three years he was a travelling tutor on the continent, and from 1859 became a school teacher in Scotland. While teaching at Greenock Academy, Stephens wrote some minor verse and two short novels ('Rutson Morley’ and 'Virtue Le Moyne’) which were published in Sharpe’s London Magazine in 1861-63.

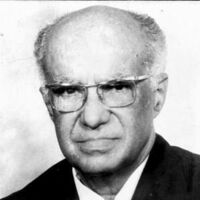

Rogelio Sinán, seudónimo de Bernardo Domínguez Alba (Taboga, 1902 - Panamá, 1994) fue un escritor vanguardista panameño. Inició sus estudios en el Colegio De La Salle y se graduó de bachiller en el Instituto Nacional de Panamá (1924). Realizó estudios universitarios en Chile, en donde conoció a los poetas Pablo Neruda y Gabriela Mistral. Siguiendo consejo de la poetisa, viaja a Italia a aprender italiano; fue allí donde se empapó de los -ismos (dadaísmo, surrealismo, creacionismo, ultrarealísmo, etc.) en boga en Europa en esa época y que serían la base de su obra posteriormente. En 1989, la Universidad de Panamá lo distinguió con el Doctorado Honori0 Vida profesional En Panamá, ejerció como profesor de español, en el Instituto Nacional y de arte dramático en la Universidad de Panamá. Posteriormente desempeñó el cargo de Primer Secretario de la Embajada de Panamá en México y, en 1938, como Cónsul de Panamá en Calcuta, India. Nuevamente en Panamá, en 1946 fue Director del Departamento de Bellas Artes y Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación. Fue miembro de la Academia Panameña de la Lengua. Premios y distinciones * Casa de Rogelio Sinán en la Isla de Taboga * Premio Ricardo Miró de Novela por su libro "Plenilunio". Panamá, 1943. * Premio Interamericano de Cuento, por su cuento "La boina roja". México, 1949. * Premio "Ricardo Miró" de Poesía por su libro "Semana Santa en la niebla". Panamá, 1949. * Premio "Ricardo Miró" de Novela por su libro "La isla mágica". Panamá, 1977. + El gobierno panameño le otorgó tres condecoraciones en vida. La Academia Panameña de * la Lengua le otorgó la Primera Orden al Mérito Intelectual. * Actualmente se entregan tres premios literarios en su honor: el Premio Centroamericano de Literatura "Rogelio Sinán", que desde 1996 convoca para libros inéditos en los géneros cuento, novela y poesía la Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá; y la Condecoración + "Rogelio Sinán" que la República de Panamá otorga cada dos años a un autor panameño por la excelencia en la obra de toda una vida. Obra literaria La obra con que Sinán se dio a conocer fue la colección de poemas Onda (1929), publicado en Roma, Italia. Con este poemario, Sinán rompe con la estética del modernismo, cultivada por los poetas románticos panameños hasta la fecha, e inicia el vanguardismo en Panamá. Esta obra representó un cambio en la visión poética del mundo y en la forma de expresión con respecto a la poesía que se practicaba en Panamá en ese momento. Aparte de la poesía, Sinán cultivó el género del cuento y la novela, y en menor medida el teatro infantil y el ensayo. Poesía * Onda. Casa Editrice, Roma, Italia, 1929; Segunda edición, Revista "Lotería", No. 11, Panamá, septiembre de 1964; Tercera edición, Ediciones Formato Dieciséis, Universidad de Panamá, 1983. * Incendio. Cuadernos de poesía "Mar del Sur", No. 1, Panamá, 1944. * Semana Santa en la niebla. Panamá, 1949; Segunda edición, Dirección Nacional de Cultura del Ministerio de Educación, Panamá, 1969. * Saloma sin salomar. Dirección Nacional de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación, Panamá, 1969. * Poesía completa de Rogelio Sinán. Prólogo de Elsie Alvarado de Ricord, compilación e introducción de Enrique Jaramillo Levi. Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá, abril de 2000. Cuento * A la orilla de las estatuas maduras. Panamá, 1946; Secretaría de Educación Pública, México, 1967. * Todo un conflicto de sangre. Panamá, 1946. * Dos aventuras en el lejano oriente. Panamá, 1947; Panamá, 1953. * La boina roja y otros cuentos. Panamá, 1954; Ediciones del Ministerio de Educación, Panamá, 1961; Madrid, 1972. Posteriormente se han seguido publicando múltiples ediciones sin las últimas tres palabras del título original. * Los pájaros del sueño. Panamá, 1957. * Cuna común. Ediciones de la revista “Tareas”, Panamá, 1963. * Cuentos de Rogelio Sinán. Editorial Universitaria Centroamericana, San José (Costa Rica), 1971; 1972. * Homenaje a Rogelio Sinán. Poesía y Cuento. Prólogo de Enrique Jaramillo Levi, Editorial Signos, México, 1982. * El candelabro de los malos ofidios y otros cuentos. Editorial Signos, Panamá, 1982. Novela * Plenilunio. Panamá,1947; México, 1953; Panamá, 1961; Madrid, 1972. Posteriormente se ha seguido publicando múltiples ediciones en Panamá. * La isla mágica. Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Panamá, 1979; Segunda edición, Ediciones * Casa de las Américas, Habana, Cuba, 1985 . Teatro infantil * La cucarachita mandinga (farsa, adaptación de una historia tradicional de la India). Panamá, 1937; Segunda edición, Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Panamá, 1992. * Chiquilinga (farsa). Panamá, 1961. * Lobo go home (escenificada en Panamá, pero no publicada como libro). Ensayo * Los valores humanos en la lírica de Maples Arce. México, 1959. * Otros ensayos aparecidos en revistas y periódicos en diversas épocas fueron reunidos por Enrique Jaramillo Levi en: “Maga, Revista panameña de cultura”, No. 5-6, Panamá, enero-junio de 1985. REferencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rogelio_Sin%C3%A1n

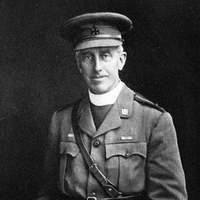

Frederick George Scott (7 April 1861– 19 January 1944) was a Canadian poet and author, known as the Poet of the Laurentians. He is sometimes associated with Canada’s Confederation Poets, a group that included Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, and Duncan Campbell Scott. Scott published 13 books of Christian and patriotic poetry. Scott was a British imperialist who wrote many hymns to the British Empire—eulogizing his country’s roles in the Boer Wars and World War I. Many of his poems use the natural world symbolically to convey deeper spiritual meaning. Frederick George Scott was the father of poet F. R. Scott.

Anna Thilda May “May” Swenson (28 May 1913– 4 December 1989) was an American poet and playwright. She is considered one of the most important and original poets of the 20th century, as often hailed by the noted critic Harold Bloom. The first child of Margaret and Dan Arthur Swenson, she grew up as the eldest of ten children in a Mormon household where Swedish was spoken regularly and English was a second language. As a lesbian, she was somewhat shunned by her family for religious reasons. Much of her later poetry works were devoted to children. She also translated the work of contemporary Swedish poets, including the selected poems of Nobel laureate Tomas Tranströmer.

Cécile Sauvage, « poétesse de la maternité »ne femme de lettres française, née à La Roche-sur-Yon le 20 juillet 1883 et morte le 26 août 1927. Biographie De 1888 à 1907, elle vécut à Digne-les-Bains, dans une maison située avenue de Verdun, où est apposée une plaque qui lui rend hommage. Étudiante au lycée de Digne, elle envoie un manuscrit Les Trois Muses à La Revue forézienne, dont le rédacteur est Pierre Messiaen. Ils échangent une correspondance, puis se marient « Notre mariage eut lieu le 9 septembre 1907, en l’église des Sieyes, près Digne (Basses-Alpes) » . Ils seront les parents d’Alain Messiaen et Olivier Messiaen qu’elle éleva, selon ce dernier, dans un « univers féerique ». Le couple est uni et heureux ; Cécile dédie Primevère à son cher Pierrot, en souvenir de nos fiançailles et de notre mariage. Elle vécut la majeure partie de sa vie à Saint-Étienne[réf. nécessaire], et écrit chaque jour à sa petite table de bois blanc tachée d’encre. Elle découvre les poètes anglais, dont Keats dont le vers La poésie de la terre ne meurt jamais semble être écrit pour illustrer la poésie de Cécile Sauvage. Elle s’installe à Grenoble avec ses fils alors que son époux part au front de la guerre 14/18 ; puis la famille vivra à Paris, qui n’attire pas la poétesse. De santé fragile, elle s’éteint le 26 août 1927, dans les bras de son époux et de ses fils. Son ami Henri Pourrat lui a consacré un ouvrage, La Veillée de novembre.

I am a very passionate winsome lad,my name is Vusumzi Mathews Sono born in the year of 1989 the 28th of December and I was born here in South Africa at a place called Cape Town,grew up in Eastern Cape.Vusi is a nickname coming from my full name Vusumzi and Oulik is just a nickname given by friends it is a Afrikaans name and it means "cute" .I never knew that one day I would be enthusiastic about poetry,but I loved writting since primary school,but then we used to just write songs that didn't even make sense but because I've never had an easy life as a child so I took out my emotions on writing as I was writing I noticed that everything I wrote was just poetic even at school when we were suppose to do orals,presentations or just anything I ended up flowing poetically,then that is when I found my first love "POETRY" inspired by roman ancient movies and some of Celine Dion's songs e.g the titanic song.

Jack Spicer (January 30, 1925– August 17, 1965) was an American poet often identified with the San Francisco Renaissance. In 2009, My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer won the American Book Award for poetry. Life and work Spicer was born in Los Angeles, where he later graduated from Fairfax High School in 1942, and attended the University of Redlands from 1943-45. He spent most of his writing-life in San Francisco and spent the years 1945 to 1950 and 1952 to 1955 at the University of California, Berkeley, where he began writing, doing work as a research-linguist, and publishing some poetry (though he disdained publishing). During this time he searched out fellow poets, but it was through his alliance with Robert Duncan and Robin Blaser that Spicer forged a new kind of poetry, and together they referred to their common work as the Berkeley Renaissance. The three, who were all gay, also educated younger poets in their circle about their “queer genealogy”, Rimbaud, Lorca, and other gay writers. Spicer’s poetry of this period is collected in One Night Stand and Other Poems (1980). His Imaginary Elegies, later collected in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry 1945-1960 anthology, were written around this time. In 1954, he co-founded the Six Gallery in San Francisco, which soon became famous as the scene of the October 1955 Six Gallery reading that launched the West Coast Beat movement. In 1955, Spicer moved to New York and then to Boston, where he worked for a time in the Rare Book Room of Boston Public Library. Blaser was also in Boston at this time, and the pair made contact with a number of local poets, including John Wieners, Stephen Jonas, and Joe Dunn. Spicer returned to San Francisco in 1956 and started working on After Lorca. This book represented a major change in direction for two reasons. Firstly, he came to the conclusion that stand-alone poems (which Spicer referred to as his one-night stands) were unsatisfactory and that henceforth he would compose serial poems. In fact, he wrote to Blaser that 'all my stuff from the past (except the Elegies and Troilus) looks foul to me.' Secondly, in writing After Lorca, he began to practice what he called “poetry as dictation”. His interest in the work of Federico García Lorca, especially as it involved the cante jondo ideal, also brought him near the poetics of the deep image group. The Troilus referred to was Spicer’s then unpublished play of that name. The play finally appeared in print in 2004, edited by Aaron Kunin, in issue 3 of No - A Journal of the Arts. In 1957, Spicer ran a workshop called Poetry as Magic at San Francisco State College, which was attended by Duncan, Helen Adam, James Broughton, Joe Dunn, Jack Gilbert, and George Stanley. He also participated in, and sometimes hosted, Blabbermouth Night at a literary bar called The Place. This was a kind of contest of improvised poetry and encouraged Spicer’s view of poetry as being dictated to the poet. After many years of alcohol abuse, Spicer fell into a prehepatic coma in his apartment building elevator, and later died aged 40 in the poverty ward of San Francisco General Hospital on August 17, 1965. Legacy Spicer’s view of the role of language in the process of writing poetry was probably the result of his knowledge of modern pre-Chomskyan linguistics and his experience as a research-linguist at Berkeley. In the legendary Vancouver lectures he elucidated his ideas on “transmissions” (dictations) from the Outside, using the comparison of the poet as crystal-set or radio receiving transmissions from outer space, or Martian transmissions. Although seemingly far-fetched, his view of language as “furniture”, through which the transmissions negotiate their way, is grounded in the structuralist linguistics of Zellig Harris and Charles Hockett. (In fact, the poems of his final book, Language, refer to linguistic concepts such as morphemes and graphemes). As such, Spicer is acknowledged as a precursor and early inspiration for the Language poets. However, many working poets today list Spicer in their succession of precedent figures. Spicer died as a result of his alcoholism. Since the posthumous publication of The Collected Books of Jack Spicer (first published in 1975), his popularity and influence has steadily risen, affecting poetry throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. In 1994, The Tower of Babel: Jack Spicer’s Detective Novel was published. Adding to the Jack Spicer revival was the publication in 1998 of two volumes: The House That Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer, edited by Peter Gizzi; and a biography: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance by Lewis Ellingham and Kevin Killian (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998). A collected works entitled My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer (Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian, editors) was published by Wesleyan University Press in November 2008, and won the American Book Award in 2009. A collection of critical essays entitled After Spicer: Critical Essays (John Emil Vincent, editor) was published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011. Further reading Blaser, Robin, editor. The Collected Books of Jack Spicer. Santa Rosa, Calif.: Black Sparrow Press, 1975 A Book Of Correspondences For Jack Spicer. Edited By David Levi Strauss and Benjamin Hollander. San Francisco: A Journal of Acts (#6), 1987; (Note: this is a collection of essays, poetry, and documents celebrating Spicer) Diaman, N. A.. Following My Heart: A Memoir. San Francisco: Persona Press, May 2007 _____. The City: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, August 2007 _____. Sitting With Jack At The Poets Table. Los Angeles: The Advocate, 1984 _____. Second Crossing: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, 1982 Ellingham, Lewis, and Kevin Killian. Poet, Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Foster, Edward Halsey. Jack Spicer. Boise, Idaho: Boise State University, 1991 Gizzi, Peter, editor. The House that Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Spicer, Jack. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part 1, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, introduction by David Hadbawnik, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 _____. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part II, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, afterword by Sean Reynolds, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 Tallman, Warren. In the Midst. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1992 Herndon, James. Everything as Expected San Francisco, 1973 Vincent, John Emil, editor. After Spicer: Critical Essays. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2011 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Spicer

Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, k (nown in English as George Santayana (/ˌsæntiˈænə/ or /-ˈɑːnə/; December 16, 1863– September 26, 1952), was a philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. Originally from Spain, Santayana was raised and educated in the United States from the age of eight and identified himself as an American, although he always kept a valid Spanish passport. He wrote in English and is generally considered an American man of letters. At the age of forty-eight, Santayana left his position at Harvard and returned to Europe permanently, never to return to the United States. His last wish was to be buried in the Spanish pantheon in Rome. Santayana is popularly known for aphorisms, such as “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” “Only the dead have seen the end of war,”, and the definition of beauty as “pleasure objectified”. Although an atheist, he always treasured the Spanish Catholic values, practices and world-view with which he was brought up. Santayana was a broad-ranging cultural critic spanning many disciplines. Early life Born Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás on December 16, 1863, in Madrid, he spent his early childhood in Ávila, Spain. His mother, Josefina Borrás, was the daughter of a Spanish official in the Philippines, and Jorge was the only child of her second marriage. She was the widow of George Sturgis, a Boston merchant with whom she had five children, two of whom died in infancy. She lived in Boston for a few years following her husband’s death in 1857, but in 1861 moved with her three surviving children to live in Madrid. There she encountered Agustín Ruiz de Santayana, an old friend from her years in the Philippines. They married in 1862. A colonial civil servant, Ruiz de Santayana was also a painter and minor intellectual. The family lived in Madrid and Ávila until 1869, when Josefina Borrás de Santayana returned to Boston with her three Sturgis children, as she had promised her first husband to raise the children in the United States. She left the six-year-old Jorge with his father in Spain. Jorge and his father followed her in 1872, but his father, finding neither Boston nor his wife’s attitude to his liking, soon returned alone to Ávila. He remained there the rest of his life. Jorge did not see him again until he entered Harvard College and took his summer vacations in Spain. Sometime during this period, Jorge’s first name was anglicized as George, the English equivalent. Education Santayana attended Boston Latin School and Harvard College, where he studied under the philosophers William James and Josiah Royce and was involved in eleven clubs as an alternative to athletics. He was founder and president of the Philosophical Club, a member of the literary society known as the O.K., an editor and cartoonist for The Harvard Lampoon, and co-founder of the literary journal The Harvard Monthly. In December, 1885, he played the role of Lady Elfrida in the Hasty Pudding theatrical Robin Hood, followed by the production Papillonetta in the spring of his senior year. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard in 1886, Santayana studied for two years in Berlin. He then returned to Harvard to write his dissertation on Hermann Lotze and teach philosophy, becoming part of the Golden Age of the Harvard philosophy department. Some of his Harvard students became famous in their own right, including T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Gertrude Stein, Horace Kallen, Walter Lippmann, and W. E. B. Du Bois. Wallace Stevens was not among his students but became a friend. From 1896 to 1897, Santayana studied at King’s College, Cambridge. Later life In 1912, Santayana resigned his position at Harvard to spend the rest of his life in Europe. He had saved money and been aided by a legacy from his mother. After some years in Ávila, Paris and Oxford, after 1920, he began to winter in Rome, eventually living there year-round until his death. During his forty years in Europe, he wrote nineteen books and declined several prestigious academic positions. Many of his visitors and correspondents were Americans, including his assistant and eventual literary executor, Daniel Cory. In later life, Santayana was financially comfortable, in part because his 1935 novel, The Last Puritan, had become an unexpected best-seller. In turn, he financially assisted a number of writers, including Bertrand Russell, with whom he was in fundamental disagreement, philosophically and politically. Santayana never married. His romantic life, if any, is not well understood. Some evidence, including a comment Santayana made late in life comparing himself to A. E. Housman, and his friendships with people who were openly homosexual and bisexual, has led scholars to speculate that Santayana was perhaps homosexual or bisexual himself, but it remains unclear whether he had any actual heterosexual or homosexual relationships. Philosophical work and publications Santayana’s main philosophical work consists of The Sense of Beauty (1896), his first book-length monograph and perhaps the first major work on aesthetics written in the United States; The Life of Reason five volumes, 1905–6, the high point of his Harvard career; Scepticism and Animal Faith (1923); and The Realms of Being (4 vols., 1927–40). Although Santayana was not a pragmatist in the mold of William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, Josiah Royce, or John Dewey, The Life of Reason arguably is the first extended treatment of pragmatism written. Like many of the classical pragmatists, and because he was well-versed in evolutionary theory, Santayana was committed to metaphysical naturalism. He believed that human cognition, cultural practices, and social institutions have evolved so as to harmonize with the conditions present in their environment. Their value may then be adjudged by the extent to which they facilitate human happiness. The alternate title to The Life of Reason, “the Phases of Human Progress,” is indicative of this metaphysical stance. Santayana was an early adherent of epiphenomenalism, but also admired the classical materialism of Democritus and Lucretius (of the three authors on whom he wrote in Three Philosophical Poets, Santayana speaks most favorably of Lucretius). He held Spinoza’s writings in high regard, calling him his “master and model.” Although an atheist, he held a fairly benign view of religion, in contrast to Bertrand Russell who held that religion was harmful. Santayana’s views on religion are outlined in his books Reason in Religion, The Idea of Christ in the Gospels, and Interpretations of Poetry and Religion. Santayana described himself as an “aesthetic Catholic.” He spent the last decade of his life at the Convent of the Blue Nuns of the Little Company of Mary on the Celian Hill at 6 Via Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, where he was cared for by the Irish sisters. Man of letters Santayana’s one novel, The Last Puritan, is a bildungsroman, centering on the personal growth of its protagonist, Oliver Alden. His Persons and Places is an autobiography. These works also contain many of his sharper opinions and bons mots. He wrote books and essays on a wide range of subjects, including philosophy of a less technical sort, literary criticism, the history of ideas, politics, human nature, morals, the influence of religion on culture and social psychology, all with considerable wit and humor. While his writings on technical philosophy can be difficult, his other writings are far more accessible and pithy. He wrote poems and a few plays, and left an ample correspondence, much of it published only since 2000. Like Alexis de Tocqueville, Santayana observed American culture and character from a foreigner’s point of view. Like William James, his friend and mentor, he wrote philosophy in a literary way. Ezra Pound includes Santayana among his many cultural references in The Cantos, notably in “Canto LXXXI” and “Canto XCV”. Santayana is usually considered an American writer, although he declined to become an American citizen, resided in fascist Italy for decades, and said that he was most comfortable, intellectually and aesthetically, at Oxford University. Awards * Royal Society of Literature Benson Medal, 1925. * Columbia University Butler Gold Medal, 1945. * Honorary degree from the University of Wisconsin, 1911. Legacy * Santayana is remembered in large part for his aphorisms, many of which have been so frequently used as to have become clichéd. His philosophy has not fared quite as well. He is regarded by most as an excellent prose stylist, and Professor John Lachs (who is sympathetic with much of Santayana’s philosophy) writes, in On Santayana, that his eloquence may ironically be the very cause of this neglect. * Santayana influenced those around him, including Bertrand Russell, who Santayana single-handedly steered away from the ethics of G. E. Moore. He also influenced many prominent people such as Harvard students T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Gertrude Stein, Horace Kallen, Walter Lippmann, W. E. B. Du Bois, Conrad Aiken, Van Wyck Brooks, and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, as well as Max Eastman and the poet Wallace Stevens. Stevens was especially influenced by Santayana’s aesthetics and became a friend even though Stevens did not take courses taught by Santayana. * Santayana is quoted by the Canadian-American sociologist Erving Goffman as a central influence in the thesis of his famous book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959). Religious historian Jerome A. Stone credits Santayana with contributing to the early thinking in the development of religious naturalism. English mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead quotes Santayana extensively in his magnum opus Process and Reality. * Chuck Jones used Santayana’s description of fanaticism as “redoubling your effort after you’ve forgotten your aim” to describe his cartoons starring Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner. Bibliography * * 1894. Sonnets And Other Verses. * 1896. The Sense of Beauty: Being the Outline of Aesthetic Theory. * 1899. Lucifer: A Theological Tragedy. * 1900. Interpretations of Poetry and Religion. * 1901. A Hermit of Carmel And Other Poems. * 1905–1906. The Life of Reason: or the Phases of Human Progress, 5 vols. * 1910. Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe. * 1913. Winds of Doctrine: Studies in Contemporary Opinion. * 1915. Egotism in German Philosophy. * 1920. Character and Opinion in the United States: With Reminiscences of William James and Josiah Royce and Academic Life in America. * 1920. Little Essays, Drawn From the Writings of George Santayana. by Logan Pearsall Smith, With the Collaboration of the Author. * 1922. Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies. * 1922. Poems. * 1923. Scepticism and Animal Faith: Introduction to a System of Philosophy. * 1926. Dialogues in Limbo * 1927. Platonism and the Spiritual Life. * 1927–40. The Realms of Being, 4 vols. * 1931. The Genteel Tradition at Bay. * 1933. Some Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy: Five Essays * 1935. The Last Puritan: A Memoir in the Form of a Novel. * 1936. Obiter Scripta: Lectures, Essays and Reviews. Justus Buchler and Benjamin Schwartz, eds. * 1944. Persons and Places. * 1945. The Middle Span. * 1946. The Idea of Christ in the Gospels; or, God in Man: A Critical Essay. * 1948. Dialogues in Limbo, With Three New Dialogues. * 1951. Dominations and Powers: Reflections on Liberty, Society, and Government. * 1953. My Host The World * Posthumous edited/selected works * 1955. The Letters of George Santayana. Daniel Cory, ed. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York. (296 letters) * 1956. Essays in Literary Criticism of George Santayana. Irving Singer, ed. * 1957. The Idler and His Works, and Other Essays. Daniel Cory, ed. * 1967. The Genteel Tradition: Nine Essays by George Santayana. Douglas L. Wilson, ed. * 1967. George Santayana’s America: Essays on Literature and Culture. James Ballowe, ed. * 1967. Animal Faith and Spiritual Life: Previously Unpublished and Uncollected Writings by George Santayana With Critical Essays on His Thought. John Lachs, ed. * 1968. Santayana on America: Essays, Notes, and Letters on American Life, Literature, and Philosophy. Richard Colton Lyon, ed. * 1968. Selected Critical Writings of George Santayana, 2 vols. Norman Henfrey, ed. * 1969. Physical Order and Moral Liberty: Previously Unpublished Essays of George Santayana. John and Shirley Lachs, eds. * 1979. The Complete Poems of George Santayana: A Critical Edition. Edited, with an introduction, by W. G. Holzberger. Bucknell University Press. * 1995. The Birth of Reason and Other Essays. Daniel Cory, ed., with an Introduction by Herman J. Saatkamp, Jr. Columbia Univ. Press. * 2009. The Essential Santayana. Selected Writings Edited by the Santayana Edition, Compiled and with an introduction by Martin A. Coleman. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. * The Works of George Santayana * Unmodernized, critical editions of George Santayana’s published and unpublished writing. The Works is edited by the Santayana Edition and published by The MIT Press. * 1986. Persons and Places. Santayana’s autobiography, incorporating Persons and Places, 1944; The Middle Span, 1945; and My Host the World, 1953. * 1988 (1896). The Sense of Beauty: Being the Outline of Aesthetic Theory. * 1990 (1900). Interpretations of Poetry and Religion. * 1994 (1935). The Last Puritan: A Memoir in the Form of a Novel. * The Letters of George Santayana. Containing over 3,000 of his letters, many discovered posthumously, to more than 350 recipients. * 2001. Book One, 1868–1909. * 2001. Book Two, 1910–1920. * 2002. Book Three, 1921–1927. * 2003. Book Four, 1928–1932. * 2003. Book Five, 1933–1936. * 2004. Book Six, 1937–1940. * 2006. Book Seven, 1941–1947. * 2008. Book Eight, 1948–1952. * 2011. George Santayana’s Marginalia: A Critical Selection, Books 1 and 2. Compiled by John O. McCormick and edited by Kristine W. Frost. * The Life of Reason in five books. * 2011 (1905). Reason in Common Sense. * 2013 (1905). Reason in Society. * 2014 (1905). Reason in Religion. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Santayana

James Kenneth Stephen (25 February 1859– 3 February 1892) was an English poet, and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, eldest son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales. Early life Stephen was the second son of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, barrister-at-law, and his wife Mary Richenda Cunningham. James Kenneth Stephen was known as 'Jem’ among his family and close friends; he was first cousin to Virginia Woolf (née Stephen). He was a King’s Scholar at Eton, where he proved to be a highly competent player of the Eton Wall Game; and then went up to King’s College, Cambridge, again as a King’s Scholar. In the Michaelmas term of 1880, he was President of the Cambridge Union Society. In 1883 he became tutor to Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, and was made a Fellow of King’s College in 1885. He was a renowned intellectual; and it was said that he spoke in a pedantic, but highly articulate and entertaining manner. Poetry Stephen became a published poet, his work being identified by the initials J. K. S. His collections of poems Lapsus Calami and Quo Musa Tendis were both published in 1891. Rudyard Kipling called him “that genius” and told how he “dealt with Haggard and me in some stanzas which I would have given much to have written myself”. Those stanzas, in which Stephen deplores the state of contemporary writing, appear in his poem ‘To R. K.’: Will there never come a season Which shall rid us from the curse Of a prose which knows no reason And an unmelodious verse: When the world shall cease to wonder At the genius of an Ass, And a boy's eccentric blunder Shall not bring success to pass: When mankind shall be delivered From the clash of magazines, And the inkstand shall be shivered Into countless smithereens: When there stands a muzzled stripling, Mute, beside a muzzled bore: When the Rudyards cease from Kipling And the Haggards Ride no more. “The Last Ride Together (From Her Point of View)” parodies Robert Browning’s “Last Ride Together”; Lord Byron is parodied in “A Grievance”; and William Wordsworth in “A Sonnet”: Two voices are there: one is of the deep; It learns the storm-cloud's thunderous melody, Now roars, now murmurs with the changing sea, Now bird-like pipes, now closes soft in sleep: And one is of an old half-witted sheep Which bleats articulate monotony, And indicates that two and one are three, That grass is green, lakes damp, and mountains steep: And, Wordsworth, both are thine J. K Stephen was at Cambridge at the same time as the distinguished antiquarian and writer of ghost-stories, Montague R. James, and mentions him at the end of a curious Latin celebration of then-current worthies of 'Coll. Regale’ (King’s College): Vivat J.K. Stephanus, Humilis poeta! Vivat Monty Jamesius, Vivant A, B, C, D, E Et totus Alphabeta! Stephen wrote a satirical pastiche of Thomas Gray’s “Ode to the Distant Prospect of Eton College” pillorying Eton for being Tory. A poem which gave him a reputation as a misogynist is “Men and Women,” where he describes two people, a man and a woman, whom he does not know but to whom he takes a violent dislike. The first part, subtitled “In the Backs” (The Backs is a riverside area of Cambridge), concludes ...I do not want to see that girl again: I did not like her: and I should not mind If she were done away with, killed, or ploughed. She did not seem to serve a useful end: And certainly she was not beautiful. (Plough is slang for failing an exam.) However many of his other poems show that this “misogyny” Is more accurately described as only one facet of a sardonic nature. Stephen was a member of the Cambridge “Apostles”. Death Stephen suffered a serious head injury in an accident in the winter of 1886/1887 which may have exacerbated the bi-polar disorder from which he suffered. His cousin Virginia Woolf suffered from the same disorder throughout her adult life. Stephen was eventually committed to St Andrew’s Hospital, a mental asylum in Northampton. In January 1892 the former Royal tutor heard that his erstwhile pupil, the 28-year-old Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence had died of pneumonia at Sandringham, after contracting influenza. On hearing the news, Stephen refused to eat, and died twenty days later, aged 32. His cause of death, according to the death certificate, was mania. Eton legacies Stephen was noted for his prodigious size and physical strength. At Eton, he was an outstanding player of the Wall Game. He played for College on St Andrew’s Day four times: in 1874, 1875, 1876 and 1877. In the last two years he was Keeper (or captain) of the College Wall. College beat the Oppidans by 4 shies to nil in his first year as Keeper, and by 10 shies to nil the next year. Ever after, the King’s Scholars have honoured J K Stephen’s memory with a toast at the Christmas Sock Supper or other festive occasions - in piam memoriam, J. K. S. (In pious memory of J. K. S.). Stephen was recalled in less pious memory in a play by former Eton housemaster and Old Etonian, Angus Graham-Campbell; entitled Sympathy for the Devil, it premiered at the Eton Drama festival in 1993. This was based on the notion that Stephen could have been one of the Jack the Ripper suspects; this theory has been dismissed, because he would have been unable to return to Cambridge in time for lectures the following morning. Stephen’s poem The Old School List from Quo Musa Tendis is included in the front pages of H. E. C. Stapleton’s Eton School Lists 1853-1892, and the author refers to him in the preface as 'an Etonian of great promise, who died only too early for his numerous friends’. During his time at Eton, Stephen was a friend of Harry Goodhart (1858–1895), who became an England international footballer and later a Professor at the University of Edinburgh. Goodhart is referred to as “one of them’s wed” in the last verse of The Old School List: There were two good fellows I used to know. —How distant it all appears! We played together in football weather, And messed together for years: Now one of them's wed, and the other's dead So long that he's hardly missed Save by us, who messed with him years ago: But we're all in the old School List. Collections Select Poems 1926 Augustan Books of Modern Poetry Lapsus Calami JKS Cambridge 1891 Quo Musa Tendis Cambridge 1891 Lapsus Calami and other verses 1896 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Kenneth_Stephen

“La poesía es una bellísima doncella, casta, honesta, discreta, aguda, retirada, y que se contiene en los límites de la discreción más alta. Es amiga de la soledad, las fuentes la entretienen, los prados la consuelan, los árboles la desenojan, las flores la alegran, y, finalmente, deleita y enseña a cuantos con ella comunican.” Miguel de Cervantes.

Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve est un critique litté, raire et écrivain français, né le 23 décembre 1804 à Boulogne-sur-Mer et mort le 13 octobre 1869 à Paris. La méthode critique de Sainte-Beuve se fonde sur le fait que l’œuvre d’un écrivain serait avant tout le reflet de sa vie et pourrait s’expliquer par elle. Elle se fonde sur la recherche de l’intention poétique de l’auteur (intentionnisme) et sur ses qualités personnelles (biographisme). Cette méthode a été critiquée par la suite. Marcel Proust, dans son essai Contre Sainte-Beuve, est le premier à la contester, reprochant de plus à Sainte-Beuve de négliger, voire condamner de grands auteurs comme Baudelaire, Stendhal ou Balzac. L’école formaliste russe, ainsi que les critiques Ernst Robert Curtius et Leo Spitzer, suivront Proust dans cette route. Cette opposition entre Sainte-Beuve et Proust peut aussi se comprendre comme un renversement de perspective de la critique littéraire. En effet, il faut reconnaître à Sainte-Beuve une capacité de critique formelle fondée: il l’a montré avec le Salammbô de Flaubert, si bien que Flaubert lui-même en tint compte dans la suite de son œuvre. Seulement, chez lui, cette analyse semble devoir rester subordonnée à la connaissance de la vie de l’auteur, et c’est là que s’opère le renversement proustien: si rapport il y a entre l’œuvre et la vie de son auteur, pour Proust c’est bien la première qui doit apparaître comme la plus riche source d’enseignements sur le sens profond de la seconde. Ce renversement est à la base de la poétique de Proust et s’incarne dans À la recherche du temps perdu. S’il est moins connu du grand public de nos jours, entre 1870 et au moins jusqu’aux années 1950, il est resté longtemps l’une des figures majeures du panthéon littéraire transmis par l’école républicaine, avec Victor Hugo, Montaigne ou Lamartine, et tous les écoliers connaissaient au moins son nom. Biographie Né à Moreuil le 6 novembre 1752, le père de l’auteur, Charles-François Sainte-Beuve, contrôleur principal des droits réunis et conseiller municipal à Boulogne-sur-Mer, se marie le 30 nivôse an XII (21 janvier 1804) avec Augustine Coilliot, fille de Jean-Pierre Coilliot, capitaine de navire, née le 22 novembre 1764. Toutefois, atteint par une angine, il meurt le 12 vendémiaire an XIII (4 octobre 1804). Orphelin de père dès sa naissance le 2 nivôse an XIII (23 décembre 1804) à Boulogne-sur-Mer, Sainte-Beuve est élevé par sa mère et une tante paternelle, veuve également. En 1812, il entre en classe de sixième comme externe libre à l’institution Blériot, à Boulogne-sur-Mer, où il reste jusqu’en 1818. À cette époque, il obtient de poursuivre ses études à Paris. Placé dans l’institution Landry en septembre 1818, il suit comme externe les cours du collège Charlemagne, de la classe de troisième à la première année de rhétorique, puis ceux du collège Bourbon, où il a pour professeur Paul-François Dubois, en seconde année de rhétorique et en philosophie. En 1822, il est lauréat du Concours général, remportant le premier prix de poésie latine. Après l’obtention de son baccalauréat ès lettres, le 18 octobre 1823, il s’inscrit à la faculté de médecine le 3 novembre. Puis, conformément à l’ordonnance du 2 février 1823, qui l’exige pour les professions médicales, il prend des leçons particulières de mathématiques et passe le baccalauréat ès sciences, le 17 juillet 1824. Toutefois, alors qu’il a été nommé en 1826 externe à l’hôpital Saint-Louis avec une chambre, il abandonne ses études de médecine en 1827 pour se consacrer aux lettres. Après un article anonyme paru le 24 octobre 1824, il publie dans Le Globe, journal libéral et doctrinaire fondé par son ancien professeur, Paul-François Dubois, un article signé « Joseph Delorme » le 4 novembre. Le 2 et le 9 janvier 1827, il publie une critique élogieuse des Odes et ballades de Victor Hugo, et les deux hommes se lient d’amitié. Ensemble, ils assistent aux réunions au Cénacle de Charles Nodier à la Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal. Il a une liaison avec l’épouse de Hugo, Adèle Foucher. Le 20 septembre 1830, Sainte-Beuve et l’un des propriétaires du journal Le Globe, Paul-François Dubois, se battent en duel dans les bois de Romainville. Sous la pluie, ils échangent quatre balles sans résultats. Sainte-Beuve conserva son parapluie à la main, disant qu’il voulait bien être tué mais pas mouillé. Après l’échec de ses romans, Sainte-Beuve se lance dans les études littéraires, dont la plus connue est Port-Royal, et collabore notamment à La Revue contemporaine. Port-Royal (1837-1859), le chef-d’œuvre de Saint-Beuve, décrit l’histoire de l’abbaye de Port-Royal des Champs, de son origine à sa destruction. Ce livre résulte d’un cours donné à l’Académie de Lausanne entre le 6 novembre 1837 et le 25 mai 1838. Cette œuvre a joué un rôle important dans le renouvellement de l’histoire religieuse. Certains historiens qualifient Port-Royal de « tentative d’histoire totale ». Élu à l’Académie française le 14 mars 1844 au fauteuil de Casimir Delavigne, il est reçu le 27 février 1845 par Victor Hugo. Il est à noter que ce dernier portait néanmoins sur leurs relations un regard désabusé: « Sainte-Beuve, confiait-il à ses carnets en 1876, n’était pas poète et n’a jamais pu me le pardonner . » En 1848-1849, il accepte une chaire à l’université de Liège, où il donne un cours consacré à Chateaubriand et son groupe littéraire, qu’il publie en 1860. À partir d’octobre 1849, il publie, successivement dans Le Constitutionnel, Le Moniteur et Le Temps des feuilletons hebdomadaires regroupés en volumes sous le nom de Causeries du lundi, leur titre venant du fait que le feuilleton paraissait chaque lundi. À la différence de Hugo, il se rallie au Second Empire en 1852. Le 13 décembre 1854, il obtient la chaire de poésie latine au Collège de France, mais sa leçon inaugurale sur « Virgile et L’Énéide », le 9 mars 1855, est perturbée par des étudiants qui veulent dénoncer son ralliement. Il doit alors envoyer, le 20 mars, sa lettre de démission. Par la suite, le 3 novembre 1857, il est nommé maître de conférences à l’École normale supérieure, où il donne des cours de langue et de littérature françaises de 1858 à 1861. Sous l’Empire libéral, il est nommé au Sénat, où il siège du 28 avril 1865 jusqu’à sa mort en 1869. Dans ces fonctions, il défend la liberté des lettres et la liberté de penser. Réception Friedrich Nietzsche, pourtant adversaire déclaré de Sainte-Beuve, a incité en 1880 Ida Overbeck, femme de son ami Franz Overbeck, à traduire les Causeries du lundi en allemand. Jusque-là, Sainte-Beuve n’avait jamais été publié en allemand, malgré sa grande importance en France, car considéré en Allemagne comme représentant d’une manière détestable et typiquement française de penser. La traduction d’Ida Overbeck est parue en 1880 sous le titre Menschen des XVIII. Jahrhunderts (« l’être humain au XVIIIe siècle »). Nietzsche a écrit à Ida Overbeck le 18 août 1880: « Il y a une heure que j’ai reçu Menschen des XVIII. Jahrhunderts. [...] C’est un livre merveilleux, je crois que j’ai pleuré, et ce serait bizarre si ce petit livre ne pouvait pas exciter la même sensation chez beaucoup d’autres personnes ». La traduction d’Ida Overbeck est un document important du transfert culturel entre l’Allemagne et la France, mais fut largement ignorée. En 2014 apparut la première édition critique et annotée. Charles Maurras s’inspire directement de la méthode d’analyse du critique littéraire pour forger sa methode d’analyse politique, l’empirisme organisateur, qui aboutira chez lui au nationalisme intégral,. Œuvres Poésie * Vie, poésies et pensées de Joseph Delorme (1829) * Les Consolations (1830) * Pensées d’août (1837) * Livre d’amour (1843) * Poésies complètes (1863) Romans et nouvelles * Volupté (1834)– réédité par S.E.P.E. en 1947 avec illustrations de Marguerite Bermond. * Madame de Pontivy (1839) * Christel (1839) * Le Clou d’or qu’il dédia à Sophie de Bazancourt, femme de lettres et épouse du général François Aimé Frédéric Loyré d’Arbouville. * La Pendule (1880) Critique * Tableau historique et critique de la poésie française et du théâtre français au XVIe siècle (1828), 2 volumes * Port-Royal (1840-1859), 5 volumes * Portraits littéraires (1844 et 1876-78), 3 volumes * Portraits contemporains (1846 et 1869-71), 5 volumes * Portraits de femmes (1844 et 1870) * Les Lundis * Causeries du lundi (1851-1862), 16 volumes * Nouveaux lundis (1863-1870), 13 volumes * Premiers lundis (1874-75), 3 volumes * Étude sur Virgile (1857). Texte de cette étude annoté par Henri Goelzer en 1895. * Chateaubriand et son groupe littéraire (1860), 2 volumes * Le Général Jomini (1869) * Madame Desbordes-Valmore: sa vie et sa correspondance (1870) * M. de Talleyrand (1870) * P.-J. Proudhon (1872) * Chroniques parisiennes (1843-1845 et 1876) * Les cahiers de Sainte-Beuve (1876) * Mes poisons (1926): carnet secret édité à titre posthume Correspondance * Lettres à la princesse (Mathilde) (1873) * Correspondance (1877-78), 2 volumes * Nouvelle correspondance (1880) * Lettres à Collombet (1903) * Correspondance avec M. et Mme Juste Olivier (1904) * Lettres à Charles Labitte (1912) * Lettres à deux amies (1948) * Lettres à George Sand * Lettres à Adèle Couriard * Correspondance générale, 19 volumes Biographie * Le général Jomini, étude, Paris 1869. Texte sur Gallica Hommage * Denys Puech (1854-1942), Monument à Sainte-Beuve, 1898, Paris, jardin du Luxembourg. Les références Wikipedia – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles-Augustin_Sainte-Beuve