Info

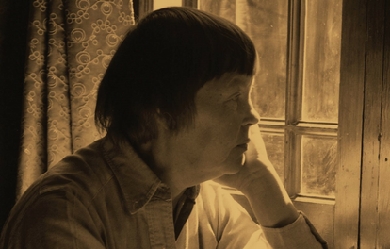

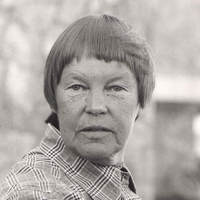

Anna Thilda May “May” Swenson (28 May 1913– 4 December 1989) was an American poet and playwright. She is considered one of the most important and original poets of the 20th century, as often hailed by the noted critic Harold Bloom. The first child of Margaret and Dan Arthur Swenson, she grew up as the eldest of ten children in a Mormon household where Swedish was spoken regularly and English was a second language. As a lesbian, she was somewhat shunned by her family for religious reasons. Much of her later poetry works were devoted to children. She also translated the work of contemporary Swedish poets, including the selected poems of Nobel laureate Tomas Tranströmer.

I'm 15 years old. I live in Missouri in the United States. I like soccer, singing, and writing. I've been writing poems and songs ever since I could pick up a pencil. Please read my poems and feedback would literally mean the world to me. You'll learn much more about me through my poems than through reading this stupid box.

Frederick George Scott (7 April 1861– 19 January 1944) was a Canadian poet and author, known as the Poet of the Laurentians. He is sometimes associated with Canada’s Confederation Poets, a group that included Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, and Duncan Campbell Scott. Scott published 13 books of Christian and patriotic poetry. Scott was a British imperialist who wrote many hymns to the British Empire—eulogizing his country’s roles in the Boer Wars and World War I. Many of his poems use the natural world symbolically to convey deeper spiritual meaning. Frederick George Scott was the father of poet F. R. Scott.

Hey everyone, I'm Erik. I've been writing poetry for about 10 years now, but I started to take it serious about a year and a half ago. A lot of my works are personal/have personal beliefs attached to them, I also want to shake things up a bit with my writing. I hope you like what I have to offer, and if you want to know any thing else find me on facebook or twitter (Skaarcia Vega) @Erik_Skaarnes.

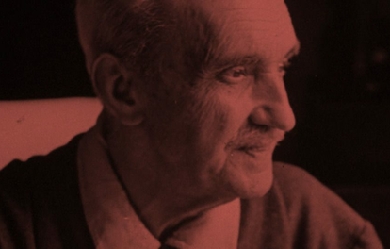

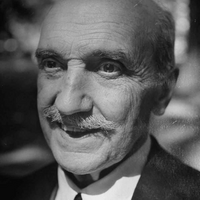

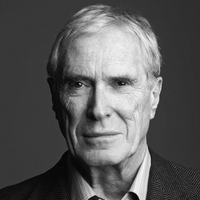

Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, k (nown in English as George Santayana (/ˌsæntiˈænə/ or /-ˈɑːnə/; December 16, 1863– September 26, 1952), was a philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. Originally from Spain, Santayana was raised and educated in the United States from the age of eight and identified himself as an American, although he always kept a valid Spanish passport. He wrote in English and is generally considered an American man of letters. At the age of forty-eight, Santayana left his position at Harvard and returned to Europe permanently, never to return to the United States. His last wish was to be buried in the Spanish pantheon in Rome. Santayana is popularly known for aphorisms, such as “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” “Only the dead have seen the end of war,”, and the definition of beauty as “pleasure objectified”. Although an atheist, he always treasured the Spanish Catholic values, practices and world-view with which he was brought up. Santayana was a broad-ranging cultural critic spanning many disciplines. Early life Born Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás on December 16, 1863, in Madrid, he spent his early childhood in Ávila, Spain. His mother, Josefina Borrás, was the daughter of a Spanish official in the Philippines, and Jorge was the only child of her second marriage. She was the widow of George Sturgis, a Boston merchant with whom she had five children, two of whom died in infancy. She lived in Boston for a few years following her husband’s death in 1857, but in 1861 moved with her three surviving children to live in Madrid. There she encountered Agustín Ruiz de Santayana, an old friend from her years in the Philippines. They married in 1862. A colonial civil servant, Ruiz de Santayana was also a painter and minor intellectual. The family lived in Madrid and Ávila until 1869, when Josefina Borrás de Santayana returned to Boston with her three Sturgis children, as she had promised her first husband to raise the children in the United States. She left the six-year-old Jorge with his father in Spain. Jorge and his father followed her in 1872, but his father, finding neither Boston nor his wife’s attitude to his liking, soon returned alone to Ávila. He remained there the rest of his life. Jorge did not see him again until he entered Harvard College and took his summer vacations in Spain. Sometime during this period, Jorge’s first name was anglicized as George, the English equivalent. Education Santayana attended Boston Latin School and Harvard College, where he studied under the philosophers William James and Josiah Royce and was involved in eleven clubs as an alternative to athletics. He was founder and president of the Philosophical Club, a member of the literary society known as the O.K., an editor and cartoonist for The Harvard Lampoon, and co-founder of the literary journal The Harvard Monthly. In December, 1885, he played the role of Lady Elfrida in the Hasty Pudding theatrical Robin Hood, followed by the production Papillonetta in the spring of his senior year. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard in 1886, Santayana studied for two years in Berlin. He then returned to Harvard to write his dissertation on Hermann Lotze and teach philosophy, becoming part of the Golden Age of the Harvard philosophy department. Some of his Harvard students became famous in their own right, including T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Gertrude Stein, Horace Kallen, Walter Lippmann, and W. E. B. Du Bois. Wallace Stevens was not among his students but became a friend. From 1896 to 1897, Santayana studied at King’s College, Cambridge. Later life In 1912, Santayana resigned his position at Harvard to spend the rest of his life in Europe. He had saved money and been aided by a legacy from his mother. After some years in Ávila, Paris and Oxford, after 1920, he began to winter in Rome, eventually living there year-round until his death. During his forty years in Europe, he wrote nineteen books and declined several prestigious academic positions. Many of his visitors and correspondents were Americans, including his assistant and eventual literary executor, Daniel Cory. In later life, Santayana was financially comfortable, in part because his 1935 novel, The Last Puritan, had become an unexpected best-seller. In turn, he financially assisted a number of writers, including Bertrand Russell, with whom he was in fundamental disagreement, philosophically and politically. Santayana never married. His romantic life, if any, is not well understood. Some evidence, including a comment Santayana made late in life comparing himself to A. E. Housman, and his friendships with people who were openly homosexual and bisexual, has led scholars to speculate that Santayana was perhaps homosexual or bisexual himself, but it remains unclear whether he had any actual heterosexual or homosexual relationships. Philosophical work and publications Santayana’s main philosophical work consists of The Sense of Beauty (1896), his first book-length monograph and perhaps the first major work on aesthetics written in the United States; The Life of Reason five volumes, 1905–6, the high point of his Harvard career; Scepticism and Animal Faith (1923); and The Realms of Being (4 vols., 1927–40). Although Santayana was not a pragmatist in the mold of William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, Josiah Royce, or John Dewey, The Life of Reason arguably is the first extended treatment of pragmatism written. Like many of the classical pragmatists, and because he was well-versed in evolutionary theory, Santayana was committed to metaphysical naturalism. He believed that human cognition, cultural practices, and social institutions have evolved so as to harmonize with the conditions present in their environment. Their value may then be adjudged by the extent to which they facilitate human happiness. The alternate title to The Life of Reason, “the Phases of Human Progress,” is indicative of this metaphysical stance. Santayana was an early adherent of epiphenomenalism, but also admired the classical materialism of Democritus and Lucretius (of the three authors on whom he wrote in Three Philosophical Poets, Santayana speaks most favorably of Lucretius). He held Spinoza’s writings in high regard, calling him his “master and model.” Although an atheist, he held a fairly benign view of religion, in contrast to Bertrand Russell who held that religion was harmful. Santayana’s views on religion are outlined in his books Reason in Religion, The Idea of Christ in the Gospels, and Interpretations of Poetry and Religion. Santayana described himself as an “aesthetic Catholic.” He spent the last decade of his life at the Convent of the Blue Nuns of the Little Company of Mary on the Celian Hill at 6 Via Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, where he was cared for by the Irish sisters. Man of letters Santayana’s one novel, The Last Puritan, is a bildungsroman, centering on the personal growth of its protagonist, Oliver Alden. His Persons and Places is an autobiography. These works also contain many of his sharper opinions and bons mots. He wrote books and essays on a wide range of subjects, including philosophy of a less technical sort, literary criticism, the history of ideas, politics, human nature, morals, the influence of religion on culture and social psychology, all with considerable wit and humor. While his writings on technical philosophy can be difficult, his other writings are far more accessible and pithy. He wrote poems and a few plays, and left an ample correspondence, much of it published only since 2000. Like Alexis de Tocqueville, Santayana observed American culture and character from a foreigner’s point of view. Like William James, his friend and mentor, he wrote philosophy in a literary way. Ezra Pound includes Santayana among his many cultural references in The Cantos, notably in “Canto LXXXI” and “Canto XCV”. Santayana is usually considered an American writer, although he declined to become an American citizen, resided in fascist Italy for decades, and said that he was most comfortable, intellectually and aesthetically, at Oxford University. Awards * Royal Society of Literature Benson Medal, 1925. * Columbia University Butler Gold Medal, 1945. * Honorary degree from the University of Wisconsin, 1911. Legacy * Santayana is remembered in large part for his aphorisms, many of which have been so frequently used as to have become clichéd. His philosophy has not fared quite as well. He is regarded by most as an excellent prose stylist, and Professor John Lachs (who is sympathetic with much of Santayana’s philosophy) writes, in On Santayana, that his eloquence may ironically be the very cause of this neglect. * Santayana influenced those around him, including Bertrand Russell, who Santayana single-handedly steered away from the ethics of G. E. Moore. He also influenced many prominent people such as Harvard students T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Gertrude Stein, Horace Kallen, Walter Lippmann, W. E. B. Du Bois, Conrad Aiken, Van Wyck Brooks, and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, as well as Max Eastman and the poet Wallace Stevens. Stevens was especially influenced by Santayana’s aesthetics and became a friend even though Stevens did not take courses taught by Santayana. * Santayana is quoted by the Canadian-American sociologist Erving Goffman as a central influence in the thesis of his famous book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959). Religious historian Jerome A. Stone credits Santayana with contributing to the early thinking in the development of religious naturalism. English mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead quotes Santayana extensively in his magnum opus Process and Reality. * Chuck Jones used Santayana’s description of fanaticism as “redoubling your effort after you’ve forgotten your aim” to describe his cartoons starring Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner. Bibliography * * 1894. Sonnets And Other Verses. * 1896. The Sense of Beauty: Being the Outline of Aesthetic Theory. * 1899. Lucifer: A Theological Tragedy. * 1900. Interpretations of Poetry and Religion. * 1901. A Hermit of Carmel And Other Poems. * 1905–1906. The Life of Reason: or the Phases of Human Progress, 5 vols. * 1910. Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe. * 1913. Winds of Doctrine: Studies in Contemporary Opinion. * 1915. Egotism in German Philosophy. * 1920. Character and Opinion in the United States: With Reminiscences of William James and Josiah Royce and Academic Life in America. * 1920. Little Essays, Drawn From the Writings of George Santayana. by Logan Pearsall Smith, With the Collaboration of the Author. * 1922. Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies. * 1922. Poems. * 1923. Scepticism and Animal Faith: Introduction to a System of Philosophy. * 1926. Dialogues in Limbo * 1927. Platonism and the Spiritual Life. * 1927–40. The Realms of Being, 4 vols. * 1931. The Genteel Tradition at Bay. * 1933. Some Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy: Five Essays * 1935. The Last Puritan: A Memoir in the Form of a Novel. * 1936. Obiter Scripta: Lectures, Essays and Reviews. Justus Buchler and Benjamin Schwartz, eds. * 1944. Persons and Places. * 1945. The Middle Span. * 1946. The Idea of Christ in the Gospels; or, God in Man: A Critical Essay. * 1948. Dialogues in Limbo, With Three New Dialogues. * 1951. Dominations and Powers: Reflections on Liberty, Society, and Government. * 1953. My Host The World * Posthumous edited/selected works * 1955. The Letters of George Santayana. Daniel Cory, ed. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York. (296 letters) * 1956. Essays in Literary Criticism of George Santayana. Irving Singer, ed. * 1957. The Idler and His Works, and Other Essays. Daniel Cory, ed. * 1967. The Genteel Tradition: Nine Essays by George Santayana. Douglas L. Wilson, ed. * 1967. George Santayana’s America: Essays on Literature and Culture. James Ballowe, ed. * 1967. Animal Faith and Spiritual Life: Previously Unpublished and Uncollected Writings by George Santayana With Critical Essays on His Thought. John Lachs, ed. * 1968. Santayana on America: Essays, Notes, and Letters on American Life, Literature, and Philosophy. Richard Colton Lyon, ed. * 1968. Selected Critical Writings of George Santayana, 2 vols. Norman Henfrey, ed. * 1969. Physical Order and Moral Liberty: Previously Unpublished Essays of George Santayana. John and Shirley Lachs, eds. * 1979. The Complete Poems of George Santayana: A Critical Edition. Edited, with an introduction, by W. G. Holzberger. Bucknell University Press. * 1995. The Birth of Reason and Other Essays. Daniel Cory, ed., with an Introduction by Herman J. Saatkamp, Jr. Columbia Univ. Press. * 2009. The Essential Santayana. Selected Writings Edited by the Santayana Edition, Compiled and with an introduction by Martin A. Coleman. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. * The Works of George Santayana * Unmodernized, critical editions of George Santayana’s published and unpublished writing. The Works is edited by the Santayana Edition and published by The MIT Press. * 1986. Persons and Places. Santayana’s autobiography, incorporating Persons and Places, 1944; The Middle Span, 1945; and My Host the World, 1953. * 1988 (1896). The Sense of Beauty: Being the Outline of Aesthetic Theory. * 1990 (1900). Interpretations of Poetry and Religion. * 1994 (1935). The Last Puritan: A Memoir in the Form of a Novel. * The Letters of George Santayana. Containing over 3,000 of his letters, many discovered posthumously, to more than 350 recipients. * 2001. Book One, 1868–1909. * 2001. Book Two, 1910–1920. * 2002. Book Three, 1921–1927. * 2003. Book Four, 1928–1932. * 2003. Book Five, 1933–1936. * 2004. Book Six, 1937–1940. * 2006. Book Seven, 1941–1947. * 2008. Book Eight, 1948–1952. * 2011. George Santayana’s Marginalia: A Critical Selection, Books 1 and 2. Compiled by John O. McCormick and edited by Kristine W. Frost. * The Life of Reason in five books. * 2011 (1905). Reason in Common Sense. * 2013 (1905). Reason in Society. * 2014 (1905). Reason in Religion. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Santayana

Alan Seeger (22 June 1888– 4 July 1916) was an American poet who fought and died in World War I during the Battle of the Somme serving in the French Foreign Legion. Seeger was the uncle of American folk singer Pete Seeger, and was a classmate of T.S. Eliot at Harvard. He is most well known for having authored the poem, I Have a Rendezvous with Death, a favorite of President John F. Kennedy. A statue modeled after Seeger is found on the monument honoring fallen Americans who volunteered for France during the war, located at the Place des États-Unis, Paris. He is sometimes called the “American Rupert Brooke.” Early life Born in New York on June 22, 1888, Seeger moved with his family to Staten Island at the age of one and remained there until the age of 10. In 1900, his family moved to Mexico for two years, which influenced the imagery of some of his poetry. His brother Charles Seeger, a noted pacifist and musicologist, was the father of the American folk singers Peter “Pete” Seeger, Mike Seeger, and Margaret “Peggy” Seeger. Seeger entered Harvard in 1906 after attending several elite preparatory schools, including Hackley School. Writing At Harvard, he edited and wrote for the Harvard Monthly. Among his friends there (and afterward) was the American Communist John Reed, though the two had differing ideological views, and his Harvard class also included T.S. Eliot and Walter Lippmann, among others. After graduating in 1910, he moved to Greenwich Village for two years, where he wrote poetry and enjoyed the life of a young bohemian. During his time in Greenwich Village, he attended soirées at the Mlles. Petitpas’ boardinghouse (319 West 29th Street), where the presiding genius was the artist and sage John Butler Yeats, father of the poet William Butler Yeats. Having moved to the Latin Quarter of Paris to continue his seemingly itinerant intellectual lifestyle, on August 24, 1914, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion so that he could fight for the Allies in World War I (the United States did not enter the war until 1917). Death He was killed in action at Belloy-en-Santerre on July 4, 1916, famously cheering on his fellow soldiers in a successful charge after being hit several times by machine gun fire. Poetry Seeger’s poetry was published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in December 1916 with a 46-page introduction by William Archer. Poems, a collection of his works, was relatively unsuccessful, due, according to Eric Homberger, to its lofty idealism and language, qualities out of fashion in the early decades of the 20th century. Poems was reviewed in The Egoist, where the critic—T. S. Eliot, Seeger’s classmate at Harvard—commented that, Seeger was serious about his work and spent pains over it. The work is well done, and so much out of date as to be almost a positive quality. It is high-flown, heavily decorated and solemn, but its solemnity is thorough going, not a mere literary formality. Alan Seeger, as one who knew him can attest, lived his whole life on this plane, with impeccable poetic dignity; everything about him was in keeping. One of his more famous poems was I Have a Rendezvous with Death, published posthumously. A recurrent theme in both his poetic works and his personal writings was his desire for his life to end gloriously at an early age. This particular poem, according to the JFK Library, “was one of John F. Kennedy’s favorite poems and he often asked his wife (Jacqueline) to recite it.” Memorials On 4 July 1923, the President of the French Council of State, Raymond Poincaré, dedicated a monument in the Place des États-Unis to the Americans who had volunteered to fight in World War I in the service of France. The monument, in the form of a bronze statue on a plinth, executed by Jean Boucher, had been financed through a public subscription. Boucher had used a photograph of Seeger as his inspiration, and Seeger’s name can be found, among those of 23 others who had fallen in the ranks of the French Foreign Legion, on the back of the plinth. Also, on either side of the base of the statue, are two excerpts from Seeger’s “Ode in Memory of the American Volunteers Fallen for France”, a poem written shortly before his death on 4 July 1916. Seeger intended that his words should be read in Paris on 30 May of that year, at an observance of the American holiday, Decoration Day (later known as Memorial Day): They did not pursue worldly rewards; they wanted nothing more than to live without regret, brothers pledged to the honor implicit in living one’s own life and dying one’s own death. Hail, brothers! Goodbye to you, the exalted dead! To you, we owe two debts of gratitude forever: the glory of having died for France, and the homage due to you in our memories. Alan Seeger Natural Area, in central Pennsylvania, was named by Colonel Henry Shoemaker. It is unknown if Alan Seeger had any connection to the area or why Shoemaker chose to memorialize the poet. The area is known for its virgin trees. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Seeger

Horace Smith (born Horatio Smith) (31 December 1779 – 12 July 1849) was an English poet and novelist, perhaps best known for his participation in a sonnet-writing competition with Percy Bysshe Shelley. It was of him that Shelley said: “Is it not odd that the only truly generous person I ever knew who had money enough to be generous with should be a stockbroker? He writes poetry and pastoral dramas and yet knows how to make money, and does make it, and is still generous.” Smith was born in London, the son of a London solicitor, and the fifth of eight children. He was educated at Chigwell School with his elder brother James Smith, also a writer. Horace first came to public attention in 1812 when he and his brother James (four years older than he) produced a popular literary parody connected to the rebuilding of the Drury Lane Theatre, after a fire in which it had been burnt down. The managers offered a prize of £50 for an address to be recited at the Theatre's reopening in October. The Smith brothers hit on the idea of pretending that the most popular poets of the day had entered the competition and writing a book of addresses rejected from the competition in parody of their various styles. James wrote parodies of Wordsworth, Southey, Coleridge and Crabbe, and Horace took on Byron, Moore, Scott and Bowles. The book was a smash, and went through seven editions within three months. The Rejected Addresses still stands the most widely popular parodies ever published in the country. The book was written without malice; none of the poets caricatured took offence, while the imitation is so clever that both Byron and Scott claimed that they could scarcely believe they had not written the addresses ascribed to them. The only other collaboration by the two brothers was Horace in London (1813). Smith went on to become a prosperous stockbroker. Smith knew Shelley as a member of the circle around Leigh Hunt. Smith helped to manage Shelley's finances. Sonnet-writing competitions were not uncommon; Shelley and Keats wrote competing sonnets on the subject of the Nile River. Inspired by Diodorus Siculus (Book 1, Chapter 47), they each wrote and submitted a sonnet on the subject to The Examiner. Shelley's Ozymandias was published on 11 January 1818 under the pen name Glirastes, and Smith's On a Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below was published on 1 February 1818 with the initials H.S. (and later in his collection Amarynthus). After making his fortune, Horace Smith produced a series of historical novels: Brambletye House (1826), Tor Hill (1826), Reuben Apsley (1827), Zillah (1828), The New Forest (1829), Walter Colyton (1830), among others. Three volumes of Gaieties and Gravities, published by him in 1826, contain many clever essays both in verse and prose, but the only piece that remains much remembered is the “Address to the Mummy in Belzoni's Exhibition.” Horace Smith died at Tunbridge Wells on 12 July 1849. References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace_Smith_(poet)

I am an electrical engineer by profession and I have recently taken up this interest of writing poems, but my English vocabulary is preventing me from moving further ahead. All the same I am putting in my best and I shall not give up easy. I would appreciate all viewers of my poems to jot down any comments (compliments or critics). It would boost up my English as well as my enthusiasm to write more and better poems.

Muriel Stuart (1885, Norbury, South London– 18 December 1967), born Muriel Stuart Irwin, was a poet, the daughter of a Scottish barrister. She was particularly concerned with the topic of sexual politics, though she first wrote poems about World War I. She later gave up poetry writing; her later publications are on gardening. She was hailed by Hugh MacDiarmid as the best woman poet of the Scottish Renaissance although she was Scottish only by family origin and lived all her life in England. Despite this, his comment led to her inclusion in many Scottish anthologies. Thomas Hardy described her poetry as “superlatively good”. Like other female poets of her era, she reflects the weight of social expectations on women and the experience of post-war spinsterhood. Her most famous poem, “In the Orchard”, is entirely dialogues and in no kind of verse form, which makes it innovative for its time. She does use rhyme: a mixture of half-rhyme and rhyming couplets (a, b, a, b form). Other famous poems of hers are “The Seed Shop”, “The Fools” and “Man and his Makers”. She married twice, the second time to the publisher Alfred William Board. Later in life she stopped publishing poetry and wrote books on gardening: Fool’s Garden (1936) was a best-seller and Gardener’s Nightcap has been reprinted by Persephone Books.

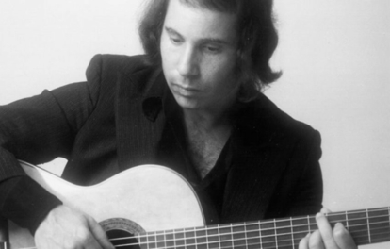

Paul Frederic Simon (born October 13, 1941) is an American musician, singer-songwriter and actor. Simon’s fame, influence, and commercial success began as part of the duo Simon & Garfunkel, formed in 1964 with musical partner Art Garfunkel. Simon wrote nearly all of the pair’s songs, including three that reached No. 1 on the U.S. singles charts: “The Sound of Silence”, “Mrs. Robinson”, and “Bridge over Troubled Water”. The duo split up in 1970 at the height of their popularity and Simon began a successful solo career as a guitarist and singer-songwriter, recording three highly acclaimed albums over the next five years. In 1986, he released Graceland, an album inspired by South African township music, which sold 14 million copies worldwide on its release and remains his most popular solo work. Simon also wrote and starred in the film One-Trick Pony (1980) and co-wrote the Broadway musical The Capeman (1998) with the poet Derek Walcott. On June 3, 2016, Simon released his 13th solo album, titled Stranger to Stranger, which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard Album Chart and the UK charts. Simon has earned sixteen Grammys for his solo and collaborative work, including three for Album of the Year (Bridge Over Troubled Water, Still Crazy After All These Years, Graceland), and a Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2001, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and in 2006 was selected as one of the "100 People Who Shaped the World" by Time magazine. In 2011, Rolling Stone magazine named Simon as one of the 100 Greatest Guitarists. In 2015, he was named as one of the 100 Greatest Songwriters by Rolling Stone. Among many other honors, Simon was the first recipient of the Library of Congress’s Gershwin Prize for Popular Song in 2007. In 1986, Simon was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Music degree from Berklee College of Music, where he currently serves on the Board of Trustees. Biography Early years Simon was born on October 13, 1941, in Newark, New Jersey, to Hungarian Jewish parents. His father, Louis (1916–1995), was a college professor, double bass player, and dance bandleader who performed under the name “Lee Sims”. His mother, Belle (1910–2007), was an elementary school teacher. In 1945, his family moved to the Kew Gardens Hills section of Flushing, Queens, in New York City. The musician Donald Fagen has described Simon’s childhood as that of “a certain kind of New York Jew, almost a stereotype, really, to whom music and baseball are very important. I think it has to do with the parents. The parents are either immigrants or first-generation Americans who felt like outsiders, and assimilation was the key thought—they gravitated to black music and baseball looking for an alternative culture.” Simon, upon hearing Fagen’s description, said it “isn’t far from the truth.” Simon says about his childhood, “I was a ballplayer. I’d go on my bike, and I’d hustle kids in stickball.” He adds that his father was a New York Yankees fan: I used to listen to games with my father. He was a nice guy. Fun. Funny. Smart. He didn’t play with me as much as I played with my kids. He was at work until late at night.... Sometimes [until] two in the morning.” Simon’s musical career began after meeting Art Garfunkel when they were both 11. They performed in a production of Alice in Wonderland for their sixth-grade graduation, and began singing together when they were 13, occasionally performing at school dances. Their idols were the Everly Brothers, whom they imitated in their use of close two-part harmony. Simon also developed an interest in jazz, folk, and blues, especially in the music of Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly. Simon’s first song written for himself and Garfunkel, when Simon was 12 or 13, was called “The Girl for Me,” and according to Simon became the “neighborhood hit.” His father wrote the words and chords on paper for the boys to use. That paper became the first officially copyrighted Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel song, and is now in the Library of Congress. In 1957, in their mid-teens, they recorded the song “Hey, Schoolgirl” under the name Tom & Jerry, given to them by their label Big Records. The single reached No. 49 on the pop charts. After graduating from Forest Hills High School, Simon majored in English at Queens College, while Garfunkel studied mathematics at Columbia University in Manhattan. Simon was a brother in the Alpha Epsilon Pi fraternity, earned a degree in English literature, and briefly attended Brooklyn Law School after graduation, but his real passion was rock and roll. Early career Between 1957 and 1964, Simon wrote, recorded, and released more than 30 songs, occasionally reuniting with Garfunkel as Tom & Jerry for some singles, including “Our Song” and “That’s My Story”. Most of the songs Simon recorded during that time were performed alone or with musicians other than Garfunkel. They were released on several minor record labels, such as Amy, Big, Hunt, King, Tribute, and Madison. He used several pseudonyms for these recordings, including Jerry Landis, Paul Kane, and True Taylor. Simon enjoyed some moderate success in recording a few singles as part of a group called Tico and the Triumphs, including a song called “Motorcycle” that reached No. 97 on the Billboard charts in 1962. Tico and the Triumphs released four 45s. Marty Cooper, known as Tico, sang lead on several of these releases. A childhood friend, Bobby Susser, children’s songwriter, record producer, and performer, co-produced the Tico 45s with Simon. That year, Simon reached No. 99 on the pop charts as Jerry Landis with the novelty song “The Lone Teen Ranger.” Both chart singles were released on Amy Records. Simon & Garfunkel In early 1964, Simon and Garfunkel got an audition with Columbia Records, whose executive Clive Davis was impressed enough to sign the duo to a contract to produce an album. Columbia decided that the two would be called simply "Simon & Garfunkel," abandoning the group’s previous name “Tom and Jerry.” Simon said in 2003 that this renaming as "Simon & Garfunkel" marked the first time artists’ surnames had been used in pop music. Simon and Garfunkel’s first LP, Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., was released on October 19, 1964; it consisted of 12 songs in the folk vein, five written by Simon. The album initially flopped. Simon moved to the UK to pursue a solo career, touring folk clubs and coffee houses. At the first club he played, the Railway Inn Folk Club in Brentwood, Essex, he met Kathy Chitty who became his girlfriend and inspiration for “Kathy’s Song,” “America,” and others. He performed at Les Cousins in London and toured provincial folk clubs that exposed him to a wide range of musical influences. In 1965, he recorded a solo LP The Paul Simon Songbook in Britain. While in the UK, Simon co-wrote several songs with Bruce Woodley of the Australian pop group the Seekers, including “I Wish You Could Be Here,” “Cloudy,” and “Red Rubber Ball.” Woodley’s co-author credit was omitted from “Cloudy” on the Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme album. The American group the Cyrkle recorded a cover of “Red Rubber Ball” that reached No. 2 in the U.S. Simon also contributed to the Seekers catalogue with “Someday One Day,” which was released in March 1966, charting around the same time as Simon and Garfunkel’s “Homeward Bound.” Back on the American East Coast, radio stations began receiving requests for one of the Wednesday Morning tracks, Simon’s “The Sound of Silence.” Their producer, Tom Wilson, overdubbed the track with electric guitar, bass guitar and drums, releasing it as a single that eventually went to No. 1 on the U.S. pop charts. The song’s success drew Simon back to the United States to reunite with Garfunkel. Together they recorded four more albums: Sounds of Silence; Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme; Bookends; and the hugely successful Bridge over Troubled Water. Simon and Garfunkel also contributed extensively to the soundtrack of the Mike Nichols film The Graduate (1967), starring Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft. While writing “Mrs. Robinson,” Simon originally toyed with the title “Mrs. Roosevelt”. When Garfunkel reported this indecision over the song’s name to the director, Nichols replied, “Don’t be ridiculous! We’re making a movie here! It’s Mrs. Robinson!” Simon and Garfunkel returned to the UK in the fall of 1968 and did a church concert appearance at Kraft Hall, which was broadcast on the BBC, and also featured Paul’s brother Ed on a performance of the instrumental “Anji.” Simon pursued solo projects after Bridge over Troubled Water, reuniting occasionally with Garfunkel for various projects, such as their 1975 Top Ten single “My Little Town.” Simon wrote it for Garfunkel, whose solo output Simon judged as lacking “bite.” The song was included on their respective solo albums—Paul Simon’s Still Crazy After All These Years and Garfunkel’s Breakaway. Contrary to popular belief, the song is not autobiographical of Simon’s early life in New York City. In 1981, they reunited again for the famous concert in Central Park, followed by a world tour and an aborted reunion album, to have been entitled Think Too Much, which was eventually released (without Garfunkel) as Hearts and Bones. Together, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990. In 2003, Simon and Garfunkel reunited once again when they received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. This reunion led to a US tour—the acclaimed “Old Friends” concert series—followed by a 2004 international encore that culminated in a free concert at the Colosseum in Rome that drew 600,000 people. In 2005, the pair sang “Mrs. Robinson” and “Homeward Bound,” plus “Bridge Over Troubled Water” with Aaron Neville, in the benefit concert From the Big Apple to The Big Easy– The Concert for New Orleans (eventually released as a DVD) for Hurricane Katrina victims. The pair reunited in April 2010 in New Orleans at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. 1971–1976 After Simon and Garfunkel split in 1970, Simon began writing and recording solo material again. His album Paul Simon was released in January 1972, preceded by his first experiment with world music, the Jamaican-inspired “Mother and Child Reunion”, at the time one of the few songs by a non-Jamaican musician to use prominent elements of reggae.. The single was a hit, reaching both the American and British Top 5. The album received universal acclaim, with critics praising the variety of styles and the confessional lyrics, reaching No. 4 in the U.S. and No. 1 in the UK and Japan. It later spawned another Top 30 hit with “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard”. Simon’s next project was the pop-folk album, There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, released in May 1973. It contained some of his most popular and polished recordings. The lead single, “Kodachrome,” was a No. 2 hit in America, and the follow-up, the gospel-flavored “Loves Me Like a Rock” was even bigger, topping the Cashbox charts. Other songs like the weary “American Tune” or the melancholic “Something So Right”—a tribute to Simon’s first wife, Peggy, which received a Grammy Award nomination for Best Song of the Year—became standards in the musician’s catalog. Critical and commercial reception for this second album was even stronger than for his debut. At the time, reviewers noted how the songs were fresh and unworried on the surface, while still exploring socially and politically conscious themes on a deeper level. The album reached No. 1 on the Cashbox album charts. As a souvenir for the tour that came next, in 1974 it was released as a live album, Live Rhymin’, which was moderately successful and displayed some changes in Simon’s music style, adopting world and religious music. Highly anticipated, Still Crazy After All These Years was his next album. Released in October 1975 and produced by Simon and Phil Ramone, it marked another departure. The mood of the album was darker, as he wrote and recorded it in the wake of his divorce. Preceded by the feel-good duet with Phoebe Snow, “Gone at Last” (a Top 25 hit) and the Simon & Garfunkel reunion track “My Little Town” (a No. 9 on Billboard), the album was his only No. 1 on the Billboard charts to date. The 18th Grammy Awards named it the Album of the Year and Simon’s performance the year’s Best Male Pop Vocal. With Simon in the forefront of popular music, the third single from the album, "50 Ways to Leave Your Lover" reached the top spot of the Billboard charts, his only single to reach No. 1 on this list. Also, on May 3, 1976, Simon put together a benefit show at Madison Square Garden to raise money for the New York Public Library. Phoebe Snow, Jimmy Cliff and the Brecker Brothers also performed. The concert produced over $30,000 for the Library. 1977–1985 After three successful studio albums, Simon became less productive during the second half of the 1970s. He dabbled in various projects, including writing music for the film Shampoo, which became the music for the song “Silent Eyes” on the “Still Crazy” album, and acting (he was cast as Tony Lacey in Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall). He achieved another hit in this decade, with the lead single of his 1977 compilation, Greatest Hits, Etc., “Slip Slidin’ Away,” reaching No. 5 in the United States. In 1980 he released One-Trick Pony, his debut album with Warner Bros. Records and his first in almost five years. It was paired with the motion picture of the same name, which Simon wrote and starred in. Although it produced his last Top 10 hit with the upbeat “Late in the Evening” (also a No. 1 hit on the Radio & Records American charts), the album did not sell well, in a music market dominated by disco music. Simon released Hearts and Bones in 1983. This was a polished and confessional album that was eventually viewed as one of his best works, but the album did not sell well when it was released. This marked a low point in Simon’s commercial popularity; both the album and the lead single, “Allergies,” missed the American Top 40. Hearts and Bones included “The Late Great Johnny Ace,” a song partly about Johnny Ace, an American R&B singer, and partly about slain Beatle John Lennon. A successful U.S. solo tour featured Simon and his guitar, with a recording of the rhythm track and horns for “Late In The Evening.” In January 1985, Simon lent his talent to USA for Africa and performed on the relief fundraising single “We Are the World.” 1986–1992 As he commented years later, after the disappointing commercial performance of Hearts and Bones, Simon felt he had lost his inspiration to a point of no return, and that his commercial fortunes were unlikely to change. While driving his car in late 1984 in this state of frustration, Simon listened to a cassette of the Boyoyo Boys’ instrumental “Gumboots: Accordion Jive Volume II” which had been lent to him by Heidi Berg, a singer songwriter he was working with at the time. Lorne Michaels had introduced Paul to Heidi when Heidi was working as the bandleader for Lorne’s “The New Show”. Interested by the unusual sound, he wrote lyrics to the number, which he sang over a re-recording of the song. It was the first composition of a new musical project that became the Grammy-award winning album Graceland, a mixture of musical styles including pop, a cappella, isicathamiya, rock, zydeco and mbaqanga. Simon travelled to South Africa to embark on further recording the album. Sessions with African musicians took place in Johannesburg in February 1985. Overdubbing and additional recording was done in April 1986, in New York. The sessions featured many South African musicians and groups, particularly Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Simon also collaborated with several American artists, singing a memorable duet with Linda Ronstadt in “Under African Skies,” and playing with Los Lobos in “All Around the World or The Myth of the Fingerprints.” Simon was briefly listed on the U.N. Boycott list but removed after he had indicated he had not violated the cultural boycott. Warner Bros. Records had serious doubts about releasing such an eclectic album to the mainstream, but did so in August 1986. Graceland was praised by critics and the public, and became Simon’s most successful solo album. Slowly climbing the worldwide charts, it reached #1 in many countries, including the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—and peaked at #3 in the U.S. It was the second-best-selling album of 1987 in the US, selling five million copies and eventually reaching 5x Platinum certification. Another seven million copies sold internationally, making it his best-selling album. The lead single was “You Can Call Me Al,” utilising a synthesizer riff played by Adrian Belew of King Crimson, a whistle solo, and an unusual bass run, in which the second half was a reversed recording of the first half. “You Can Call Me Al” was accompanied by a humorous video featuring actor Chevy Chase, which was shown on MTV. The single reached UK Top 5 and the U.S. Top 25. Further singles, including the title track, “The Boy in the Bubble” and “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” were not commercial hits but became radio standards and were highly praised. At age 45, Simon found himself back at the forefront of popular music. He received the Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1987 and also Grammy Award for Record of the Year for the title track one year later. He also embarked on the very successful Graceland Tour, which was documented on music video. Simon found himself embracing new sounds, which some critics viewed negatively—however, Simon reportedly felt it was a natural artistic experiment, considering that world music was already present on much of his early work, including such Simon & Garfunkel hits as “El Condor Pasa” and his early solo recording “Mother and Child Reunion,” which was recorded in Kingston, Jamaica. One way or another, Warner Bros. Records (who by this time controlled and reissued all his previous Columbia albums) re-established Simon as one of their most successful artists. In an attempt to capitalize on his renewed success, WB Records released the album Negotiations and Love Songs in November 1988, a mixture of popular hits and personal favorites that covered Simon’s entire career and became an enduring seller in his catalog. After Graceland, Simon decided to extend his roots with the Brazilian music-flavored The Rhythm of the Saints. Sessions for the album began in December 1989, and took place in Rio de Janeiro and New York, featuring guitarist J. J. Cale and many Brazilian and African musicians. The tone of the album was more introspective and relatively low-key compared to the mostly upbeat numbers of Graceland. Released in October 1990, the album received excellent critical reviews and achieved very respectable sales, peaking at #4 in the U.S. and No. 1 in the UK. The lead single, “The Obvious Child,” featuring the Grupo Cultural Olodum, became his last Top 20 hit in the UK and appeared near the bottom of the Billboard Hot 100. Although not as successful as Graceland, The Rhythm of the Saints was received as a competent successor and consistent complement on Simon’s attempts to explore (and popularize) world music, and also received a Grammy nomination for Album of the Year. Simon’s ex-wife Carrie Fisher said in her autobiography Wishful Drinking that the song “She Moves On” is about her. It’s one of several she claimed, followed by the line, “If you can get Paul Simon to write a song about you, do it. Because he is so brilliant at it.” The success of both albums allowed Simon to stage another New York concert. On August 15, 1991, almost a decade after his concert with Garfunkel, Simon staged a second concert in Central Park with African and South American bands. The success of the concert surpassed all expectations, and reportedly over 750,000 people attended—one of the largest concert audiences in history. He later remembered the concert as, “...the most memorable moment in my career.” The success of the show led to both a live album and an Emmy-winning TV special. In the middle, Simon embarked on the successful Born at the Right Time Tour, and promoted the album with further singles, including “Proof”—accompanied with a humorous video that again featured Chevy Chase, and added Steve Martin. On March 4, 1992, he appeared on his own episode of MTV Unplugged, offering renditions of many of his most famous compositions. Broadcast in June, the show was a success, though it did not receive an album release. 1993–1998 After Unplugged, Simon’s place in the forefront of popular music dropped notably. A Simon & Garfunkel reunion took place in September 1993, and in another attempt to capitalize on the occasion, Columbia released Paul Simon 1964/1993 in September, a three-disc compilation that received a reduced version on the two-disc album The Paul Simon Anthology one month later. In 1995 he made news for appearing on The Oprah Winfrey Show, where he performed the song “Ten Years,” which he composed specially for the tenth anniversary of the show. Also that year, he was featured on the Annie Lennox version of his 1973 song “Something So Right,” which appeared briefly on the UK Top 50 once it was released as a single in November. Since the early stages of the nineties, Simon was fully involved on The Capeman, a musical that finally opened on January 29, 1998. Simon worked enthusiastically on the project for many years and described it as "a New York Puerto Rican story based on events that happened in 1959—events that I remembered." The musical tells the story of real-life Puerto Rican youth Salvador Agron, who wore a cape while committing two murders in 1959 New York, and went on to become a writer in prison. Featuring Marc Anthony as the young Agron and Rubén Blades as the older Agron, the play received terrible reviews and very poor box office receipts from the very beginning, and closed on March 28 after just 68 performances—a failure that reportedly cost Simon 11 million dollars. Simon recorded an album of songs from the show, which was released in November 1997. It was received with very mixed reviews, though many critics praised the combination of doo-wop, rockabilly and Caribbean music that the album reflected. In commercial terms, Songs from The Capeman was a failure—it found Simon missing the Top 40 of the Billboard charts for the first time in his career. The cast album was never released on CD but eventually became available online. 1999–2007 After the disaster of The Capeman, Simon’s career was again in an unexpected crisis. However, entering the new millennium, he maintained a respectable reputation, offering critically acclaimed new material and receiving commercial attention. In 1999, Simon embarked on a North American tour with Bob Dylan, where each alternated as headline act with a “middle” section where they performed together, starting on the first of June and ending September 18. The collaboration was generally well-received, with just one critic, Seth Rogovoy, from the Berkshire Eagle, questioning the collaboration. In an attempt to return successfully to the music market, Simon wrote and recorded a new album very quickly, with You’re the One arriving in October 2000. The album consisted mostly of folk-pop writing combined with foreign musical sounds, particularly grooves from North Africa. While not reaching the commercial heights of previous albums, it managed at least to reach both the British and American Top 20. It received favorable reviews and received a Grammy nomination for Album of the Year. He toured extensively for the album, and one performance in Paris was released to home video. In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Simon sang “Bridge Over Troubled Water” on America: A Tribute to Heroes, a multinetwork broadcast to benefit the September 11 Telethon Fund. In 2002, he wrote and recorded “Father and Daughter,” the theme song for the animated family film The Wild Thornberrys Movie. The track was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Song. In 2003, he participated on another Simon & Garfunkel reunion. One year later, Simon’s studio albums were re-released both individually and together in a limited-edition nine-CD boxed set, Paul Simon: The Studio Recordings 1972–2000. At the time, Simon was already working on a new album with Brian Eno called Surprise, which was released in May 2006. Most of the album was inspired by the September 11 terrorist attacks, the Iraq invasion, and the war that followed. In personal terms, Simon was also inspired by the fact of having turned 60 in 2001, which he humorously referred to on “Old” from You’re the One. Surprise was a commercial hit, reaching #14 in the Billboard 200 and #4 in the UK. Most critics also praised the album, and many of them called it a “comeback”. Stephen Thomas Erlewine from AllMusic wrote that “Simon doesn’t achieve his comeback by reconnecting with the sound and spirit of his classic work; he has achieved it by being as restless and ambitious as he was at his popular and creative peak, which makes Surprise all the more remarkable.” The album was supported with the successful Surprise Tour from May-November 2006. In March 2004, Walter Yetnikoff published a book called 'Howling at the Moon’, in which he criticized Simon personally and for his tenuous business partnership with Columbia Records in the past. In 2007 Simon was the inaugural recipient of the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, awarded by the Library of Congress, and later performed as part of a gala of his work. 2008–2013 After living in Montauk, New York, for many years, Simon relocated to New Canaan, Connecticut. Simon is one of a small number of performers who are named as the copyright owner on their recordings (most records have the recording company as the named owner of the recording). This noteworthy development was spearheaded by the Bee Gees after their successful $200 million lawsuit against RSO Records, which remains the largest successful lawsuit against a record company by an artist or group. All of Simon’s solo recordings, including those originally issued by Columbia Records, are currently distributed by Sony Records’ Legacy Recordings unit. His albums were issued by Warner Music Group until mid-2010. In mid-2010, Simon moved his catalog of solo work from Warner Bros. Records to Sony/Columbia Records where Simon and Garfunkel’s catalog is. Simon’s back catalog of solo recordings would be marketed by Sony Music’s Legacy Recordings unit. In February 2009, Simon performed back-to-back shows in New York City at the Beacon Theatre, which had recently been renovated. Simon was reunited with Art Garfunkel at the first show as well as with the cast of The Capeman; also playing in the band was Graceland bassist Bakithi Kumalo. In May 2009, Simon toured with Garfunkel in Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. In October 2009, they appeared together at the 25th Anniversary of The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame concert at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The pair performed four of their most popular songs, “The Sound of Silence,” “The Boxer,” “Cecilia,” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” Simon’s album So Beautiful or So What was released on the Concord Music Group label on April 12, 2011. The album received high marks from the artist, "It’s the best work I’ve done in 20 years." It was reported that Simon attempted to have Bob Dylan guest on the album. On November 10, 2010, Simon released a new song called “Getting Ready for Christmas Day”. It premiered on National Public Radio, and was included on the album So Beautiful or So What. The song samples a 1941 sermon by the Rev. J.M. Gates, also entitled “Getting Ready for Christmas Day”. Simon performed the song live on The Colbert Report on December 16, 2010. The first video featured J.M. Gates’ giving the sermon and his church in 2010 with its display board showing many of Simon’s lyrics; the second video illustrates the song with cartoon images. In the premiere show of the final season of The Oprah Winfrey Show on September 10, 2010, Simon surprised Oprah and the audience with a song dedicated to Oprah and her show lasting 25 years (an update of a song he did for her show’s 10th anniversary). Rounding off his 2011 World Tour, which included United States, England, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany, Simon appeared at Ramat Gan Stadium in Israel in July 2011, making his first concert appearance in Israel since 1983. On September 11, 2011, Paul Simon performed “The Sound of Silence” at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, site of the World Trade Center, on the 10th anniversary of the September 11 attacks. On February 26, 2012, Simon paid tribute to fellow musicians Chuck Berry and Leonard Cohen who were the recipients of the first annual PEN Awards for songwriting excellence at the JFK Presidential Library in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1986 Simon was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Music degree from Berklee College of Music where he currently serves on the Board of Trustees. On June 5, 2012, Simon released a 25th anniversary box set of Graceland, which included a remastered edition of the original album, the 2012 documentary film Under African Skies, the original 1987 “African Concert” from Zimbabwe, an audio narrative “The Story of 'Graceland’” as told by Paul Simon, and other interviews and paraphernalia. He played a few concerts in Europe with the original musicians to commemorate the anniversary. On December 19, 2012, Simon performed at the funeral of Victoria Leigh Soto, a teacher killed in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting. On June 14, 2013, at Sting’s Back to Bass Tour, Simon performed his song “The Boxer” and Sting’s “Fields of Gold” with Sting. In September 2013, Simon delivered the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature at Emory University. 2014–present In February 2014, Simon embarked on a joint concert tour titled On Stage Together with English musician Sting, playing 21 concerts in North America. The tour continued in early 2015, with ten shows in Australia and New Zealand, and 23 concerts in Europe, ending on 18 April 2015. On August 4, 2015, Simon performed “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard”, “Homeward Bound”, and “Late in the Evening” alongside Billy Joel at the final concert of Nassau Coliseum on Long Island, New York. On September 11, 2015, Simon appeared during the premiere week of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Simon, who performed “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard” with Colbert for his surprise appearance, had been promoted prior to the show as “Simon and Garfunkel tribute band Troubled Waters.” Simon’s additional performance of “An American Tune” was posted as a bonus on the show’s YouTube channel. Simon also wrote and performed the theme song for the comedian Louis C.K.'s show Horace and Pete, which debuted January 30, 2016. The song, which can be heard during the show’s opening, intermission, and closing credits, is sparse, featuring only Simon’s voice and an acoustic guitar. Simon made a cameo appearance onscreen in the tenth and final episode of the series. On June 3, 2016 Simon released his thirteenth solo studio album, Stranger to Stranger via Concord Records. He began writing new material shortly after releasing his twelfth studio album, So Beautiful or So What, in April 2011. Simon collaborated with the Italian electronic dance music artist Clap! Clap! on three songs—"The Werewolf", “Street Angel”, and “Wristband”. Simon was introduced to him by his son, Adrian, who was a fan of his work. The two met up in July 2011 when Simon was touring behind So Beautiful or So What in Milan, Italy. He and Clap! Clap! worked together via email over the course of making the album. Simon also worked with longtime friend Roy Halee, who is listed as co-producer on the album. “I always liked working with him more than anyone else,” Simon noted. Following the release of the album, Simon noted that “showbiz doesn’t hold any interest for me” and discussed future retirement as “I am going to see what happens if I let go”. On July 25, 2016, he performed “Bridge over Troubled Water” at the 2016 Democratic National Convention. On May 24, 2017, he debuted “Questions for the Angels” with jazz guitarist Bill Frisell on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Songwriting In an in-depth interview reprinted in American Songwriter, Simon discusses the craft of songwriting with music journalist Tom Moon. In the interview, Simon explains the basic themes in his songwriting: love, family, social commentary, etc., as well as the overarching messages of religion, spirituality, and God in his lyrics. Simon goes on in the interview to explain the process of how he goes about writing songs, “The music always precedes the words. The words often come from the sound of the music and eventually evolve into coherent thoughts. Or incoherent thoughts. Rhythm plays a crucial part in the lyric-making as well. It’s like a puzzle to find the right words to express what the music is saying.” Projects Music for Broadway In the late 1990s, Simon wrote and produced a Broadway musical called The Capeman, which lost $11 million during its 1998 run. In April 2008, the Brooklyn Academy of Music celebrated Paul Simon’s works, and dedicated a week to Songs From the Capeman with a good portion of the show’s songs performed by a cast of singers and the Spanish Harlem Orchestra. Simon himself appeared during the BAM shows, performing “Trailways Bus” and “Late In the Evening”. In August 2010, The Capeman was staged for three nights in the Delacorte Theatre in New York’s Central Park. The production was directed by Diane Paulus and produced in conjunction with the Public Theater. Film and television Simon has also dabbled in acting. He played music producer Tony Lacey, a supporting character, in the 1977 Woody Allen feature film Annie Hall. He wrote and starred in 1980's One Trick Pony as Jonah Levin, a journeyman rock and roller. Simon also wrote all the songs in the film. Paul Simon also appeared on The Muppet Show (the only episode to use only the songs of one songwriter, Simon). In 1990, he played the character of—appropriately enough—Simple Simon on the Disney Channel TV movie, Mother Goose Rock 'n’ Rhyme. In 1978, Simon made a cameo appearance in the movie, The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash. He has been the subject of two films by Jeremy Marre, the first on Graceland, the second on The Capeman. On November 18, 2008, Simon was a guest on The Colbert Report promoting his book Lyrics 1964–2008. After an interview with Stephen Colbert, Simon performed “American Tune”. Simon performed a Stevie Wonder song at the White House in 2009 at an event honoring Wonder’s musical career and contributions. In May 2009, The Library of Congress: Paul Simon and Friends Live Concert was released on DVD, via Shout! Factory. The PBS concert was recorded in 2007. In April 2011 Simon was confirmed to appear at the Glastonbury music festival in England. Saturday Night Live Simon has appeared on Saturday Night Live (SNL), either as host or musical guest, 14 times. On one appearance in the late 1980s, he worked with his political namesake, Illinois Senator Paul Simon. Simon’s most recent SNL appearance on a Saturday night was on the March 9, 2013 episode hosted by Justin Timberlake as a member of the Five-Timers Club. In one SNL skit from 1986 (when he was promoting Graceland), Simon plays himself, waiting in line with a friend to get into a movie. He amazes his friend by remembering intricate details about prior meetings with passers-by, but draws a complete blank when approached by Art Garfunkel, despite the latter’s numerous memory prompts. Simon appeared alongside George Harrison as musical guest on the Thanksgiving Day episode of SNL (November 20, 1976). The two performed “Here Comes the Sun” and “Homeward Bound” together, while Simon performed "50 Ways to Leave Your Lover" solo earlier in the show. On that episode, Simon opened the show performing “Still Crazy After All These Years” in a turkey outfit, since Thanksgiving was the following week. About halfway through the song, Simon tells the band to stop playing because of his embarrassment. After giving a frustrating speech to the audience, he leaves the stage, backed by applause. Lorne Michaels positively greets him backstage, but Simon is still upset, yelling at him because of the humiliating turkey outfit. This is one of SNL’s most played sketches. Simon closed the 40th anniversary SNL show on February 15, 2015, with a performance of “Still Crazy After All These Years,” sans turkey outfit. Simon also played a snippet of “I’ve Just Seen a Face” with Sir Paul McCartney during the special’s introductory sequence. On September 29, 2001, Simon made a special appearance on the first SNL to air after the September 11, 2001 attacks. On that show, he performed “The Boxer” to the audience and the NYC firefighters and police officers. He is also a friend of former SNL star Chevy Chase, who appeared in his video for “You Can Call Me Al” lip synching the song while Simon looks disgruntled and mimes backing vocals and the playing of various instruments beside him. Chase would also appear in Simon’s 1991 video for the song “Proof” alongside Steve Martin. He is a close friend of SNL producer Lorne Michaels, who produced the 1977 TV show The Paul Simon Special, as well as the Simon and Garfunkel concert in Central Park four years later. Simon and Lorne Michaels were the subjects of a 2006 episode of the Sundance Channel documentary series, Iconoclasts. Awards and honors * Simon has won 12 Grammy Awards (one of them a Lifetime Achievement Award) and five Album of the Year Grammy nominations, the most recent for You’re the One in 2001. He is one of only five artists to have won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year more than once as the main credited artist. In 1998 he was entered in the Grammy Hall of Fame for the Simon & Garfunkel album Bridge over Troubled Water. He received an Oscar nomination for the song “Father and Daughter” in 2002. He is also a two-time inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; as a solo artist in 2001, and in 1990 as half of Simon & Garfunkel. * In 2001, Simon was honored as MusiCares Person Of The Year. The following year, he was one of the five recipients of the annual Kennedy Center Honors, the nation’s highest tribute to performing and cultural artists. In 2005, Simon was saluted as a BMI Icon at the 53rd Annual BMI Pop Awards. Simon’s songwriting catalog has earned 39 BMI Awards including multiple citations for “Bridge over Troubled Water,” “Mrs. Robinson,” “Scarborough Fair” and “The Sound of Silence”. As of 2005, he has amassed nearly 75 million broadcast airplays, according to BMI surveys. * In 2006, Simon was selected by Time Magazine as one of the "100 People Who Shaped the World.” * In 2007, Simon received the first annual Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. Named in honor of George and Ira Gershwin, this new award recognizes the profound and positive effect of popular music on the world’s culture. On being notified of the honor, Simon said, “I am grateful to be the recipient of the Gershwin Prize and doubly honored to be the first. I look forward to spending an evening in the company of artists I admire at the award ceremony in May. I can think of a few who have expressed my words and music far better than I. I’m excited at the prospect of that happening again. It’s a songwriter’s dream come true.” Among the performers who paid tribute to Simon were Stevie Wonder, Alison Krauss, Jerry Douglas, Lyle Lovett, James Taylor, Dianne Reeves, Marc Anthony, Yolanda Adams, and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. The event was professionally filmed and broadcast and is now available as Paul Simon and Friends. * In 2010, Simon received an honorary degree from Brandeis University, where he performed “The Boxer” at the main commencement ceremony. * In October 2011, Simon was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Science. At the induction ceremony, he performed “American Tune.” * In 2012, Simon was awarded the Polar Music Prize. Personal life * When Simon moved to England in 1964, he met Kathleen Mary “Kathy” Chitty (born 1947) on April 12, 1964, at the first English folk club he played, Railway Inn Folk Club in Brentwood, Essex, where Chitty worked part-time selling tickets. She was 17, he was 22, and they fell in love. Later that year they visited the U.S. together, touring around mainly by bus. Kathy returned to England on her own with Simon returning to her some weeks later. When Simon returned to the U.S. with the growing success of “The Sound of Silence”, Kathy, who was quite shy, wanted no part of the success and fame that awaited Simon and they split. She is mentioned by name in at least two of his songs: “Kathy’s Song” and “America,” and is referred to in “Homeward Bound” and “The Late Great Johnny Ace.” There is a photo of Simon and Kathy on the cover of The Paul Simon Songbook. * Simon has been married three times, first to Peggy Harper in late autumn 1969. They had a son Harper Simon in 1972 and divorced in 1975. The song “Train in the Distance,” from Simon’s 1983 album Hearts and Bones, is about this relationship. Simon’s 1972 song “Run That Body Down,” from his second solo album, casually mentions both himself and his then-wife ("Peg") by name. * His second marriage, from 1983 to 1984, was to actress and author Carrie Fisher to whom he proposed after a New York Yankees game. The song “Hearts and Bones” was written about this relationship. The song “Graceland” is also thought to be about seeking solace from the end of this relationship by taking a road trip. A year after divorcing, Simon and Fisher resumed their relationship for several years. * His third wife is folk singer Edie Brickell, 24 years his junior, whom he married on May 30, 1992. They have three children: Adrian, Lulu, and Gabriel. On April 26, 2014, Simon and Brickell were arrested at their home in New Canaan, Connecticut for disorderly conduct following an argument between the couple. They were released the next day. Prosecutors ultimately decided not to pursue domestic violence charges against the couple. * Paul Simon and his younger brother, Eddie Simon, founded the Guitar Study Center in New York City. The Guitar Study Center later became part of The New School in New York City. Philanthropy * Simon is a proponent of music education for children. In 1970, after recording his “Bridge Over Troubled Water”, at the invitation of the NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, Simon held auditions for a young songwriter’s workshop. Advertised in the Village Voice, the auditions brought hundreds of hopefuls to perform for Simon. Among the six teenage songwriters Simon selected for tutelage were Melissa Manchester, Tommy Mandel and rock/beat poet Joe Linus, with Maggie and Terre Roche (the Roche Sisters), who later sang back-up for Simon, joining the workshop in progress through an impromptu appearance. * Simon invited the six teens to experience recording at Columbia studios with engineer Roy Halee. During these sessions, Bob Dylan was downstairs recording the album Self-Portrait, which included a version of Simon’s “The Boxer”. Violinist Isaac Stern also visited the group with a CBS film crew, speaking to the young musicians about lyrics and music after Joe Linus performed his song “Circus Lion” for Stern. * Manchester later paid homage to Simon, on her recorded song, “Ode to Paul.” Other musicians Simon has mentored include Nick Laird-Clowes, who co-founded the band the Dream Academy. Laird-Clowes has credited Simon with helping to shape the band’s biggest hit, “Life in a Northern Town”. * In 2003, Simon signed on as a supporter of Little Kids Rock, a nonprofit organization that provides free musical instruments and free lessons to children in public schools in the U.S. He sits on the organization’s board of directors as an honorary member. * Simon is also a major benefactor and one of the co-founders, with Dr. Irwin Redlener, of the Children’s Health Project and The Children’s Health Fund which started by creating specially equipped “buses” to take medical care to children in medically underserved areas, urban and rural. Their first bus was in the impoverished South Bronx of New York City, but they now operate in 12 states, including on the Gulf Coast. It has expanded greatly, partnering with major hospitals, local public schools and medical schools and advocating policy for children’s health and medical care. * In May 2012, Paul Simon performed at a benefit dinner for the Turkana Basin Institute in New York City, raising more than $2 million for Richard Leakey’s research institute in Africa. Discography * This discography does not include compilation albums, concert albums, or work with Simon and Garfunkel. Simon’s solo concert albums often have songs he originally recorded with Simon and Garfunkel, and many Simon and Garfunkel concert albums contain songs Simon first recorded on solo albums. Finally, Paul Simon has a few songs that appear on compilation albums and nowhere else. For example, “Slip Slidin’ Away” appears only on the compilation albums Negotiations and Love Songs (1988) and Greatest Hits, Etc. (1977). * Studio solo albums * The Paul Simon Songbook (1965) * Paul Simon (1972) * There Goes Rhymin’ Simon (1973) * Still Crazy After All These Years (1975) * One-Trick Pony (1980) * Hearts and Bones (1983) * Graceland (1986) * The Rhythm of the Saints (1990) * Songs from The Capeman (1997) * You’re the One (2000) * Surprise (2006) * So Beautiful or So What (2011) * Stranger to Stranger (2016) Filmography Work on Broadway * Rock 'n Roll! The First 5,000 Years (1982)– revue– featured songwriter for “Mrs. Robinson” * Asinamali! (1987)– play– co-producer * Mike Nichols and Elaine May: Together Again on Broadway (1992)– concert– performer * The Capeman (1998)– composer, co-lyricist and music arranger– Tony Nomination for Best Original Score * The Graduate (2002)– play– featured songwriter References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Simon

I am a very passionate winsome lad,my name is Vusumzi Mathews Sono born in the year of 1989 the 28th of December and I was born here in South Africa at a place called Cape Town,grew up in Eastern Cape.Vusi is a nickname coming from my full name Vusumzi and Oulik is just a nickname given by friends it is a Afrikaans name and it means "cute" .I never knew that one day I would be enthusiastic about poetry,but I loved writting since primary school,but then we used to just write songs that didn't even make sense but because I've never had an easy life as a child so I took out my emotions on writing as I was writing I noticed that everything I wrote was just poetic even at school when we were suppose to do orals,presentations or just anything I ended up flowing poetically,then that is when I found my first love "POETRY" inspired by roman ancient movies and some of Celine Dion's songs e.g the titanic song.

James Kenneth Stephen (25 February 1859– 3 February 1892) was an English poet, and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, eldest son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales. Early life Stephen was the second son of Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, barrister-at-law, and his wife Mary Richenda Cunningham. James Kenneth Stephen was known as 'Jem’ among his family and close friends; he was first cousin to Virginia Woolf (née Stephen). He was a King’s Scholar at Eton, where he proved to be a highly competent player of the Eton Wall Game; and then went up to King’s College, Cambridge, again as a King’s Scholar. In the Michaelmas term of 1880, he was President of the Cambridge Union Society. In 1883 he became tutor to Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, and was made a Fellow of King’s College in 1885. He was a renowned intellectual; and it was said that he spoke in a pedantic, but highly articulate and entertaining manner. Poetry Stephen became a published poet, his work being identified by the initials J. K. S. His collections of poems Lapsus Calami and Quo Musa Tendis were both published in 1891. Rudyard Kipling called him “that genius” and told how he “dealt with Haggard and me in some stanzas which I would have given much to have written myself”. Those stanzas, in which Stephen deplores the state of contemporary writing, appear in his poem ‘To R. K.’: Will there never come a season Which shall rid us from the curse Of a prose which knows no reason And an unmelodious verse: When the world shall cease to wonder At the genius of an Ass, And a boy's eccentric blunder Shall not bring success to pass: When mankind shall be delivered From the clash of magazines, And the inkstand shall be shivered Into countless smithereens: When there stands a muzzled stripling, Mute, beside a muzzled bore: When the Rudyards cease from Kipling And the Haggards Ride no more. “The Last Ride Together (From Her Point of View)” parodies Robert Browning’s “Last Ride Together”; Lord Byron is parodied in “A Grievance”; and William Wordsworth in “A Sonnet”: Two voices are there: one is of the deep; It learns the storm-cloud's thunderous melody, Now roars, now murmurs with the changing sea, Now bird-like pipes, now closes soft in sleep: And one is of an old half-witted sheep Which bleats articulate monotony, And indicates that two and one are three, That grass is green, lakes damp, and mountains steep: And, Wordsworth, both are thine J. K Stephen was at Cambridge at the same time as the distinguished antiquarian and writer of ghost-stories, Montague R. James, and mentions him at the end of a curious Latin celebration of then-current worthies of 'Coll. Regale’ (King’s College): Vivat J.K. Stephanus, Humilis poeta! Vivat Monty Jamesius, Vivant A, B, C, D, E Et totus Alphabeta! Stephen wrote a satirical pastiche of Thomas Gray’s “Ode to the Distant Prospect of Eton College” pillorying Eton for being Tory. A poem which gave him a reputation as a misogynist is “Men and Women,” where he describes two people, a man and a woman, whom he does not know but to whom he takes a violent dislike. The first part, subtitled “In the Backs” (The Backs is a riverside area of Cambridge), concludes ...I do not want to see that girl again: I did not like her: and I should not mind If she were done away with, killed, or ploughed. She did not seem to serve a useful end: And certainly she was not beautiful. (Plough is slang for failing an exam.) However many of his other poems show that this “misogyny” Is more accurately described as only one facet of a sardonic nature. Stephen was a member of the Cambridge “Apostles”. Death Stephen suffered a serious head injury in an accident in the winter of 1886/1887 which may have exacerbated the bi-polar disorder from which he suffered. His cousin Virginia Woolf suffered from the same disorder throughout her adult life. Stephen was eventually committed to St Andrew’s Hospital, a mental asylum in Northampton. In January 1892 the former Royal tutor heard that his erstwhile pupil, the 28-year-old Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence had died of pneumonia at Sandringham, after contracting influenza. On hearing the news, Stephen refused to eat, and died twenty days later, aged 32. His cause of death, according to the death certificate, was mania. Eton legacies Stephen was noted for his prodigious size and physical strength. At Eton, he was an outstanding player of the Wall Game. He played for College on St Andrew’s Day four times: in 1874, 1875, 1876 and 1877. In the last two years he was Keeper (or captain) of the College Wall. College beat the Oppidans by 4 shies to nil in his first year as Keeper, and by 10 shies to nil the next year. Ever after, the King’s Scholars have honoured J K Stephen’s memory with a toast at the Christmas Sock Supper or other festive occasions - in piam memoriam, J. K. S. (In pious memory of J. K. S.). Stephen was recalled in less pious memory in a play by former Eton housemaster and Old Etonian, Angus Graham-Campbell; entitled Sympathy for the Devil, it premiered at the Eton Drama festival in 1993. This was based on the notion that Stephen could have been one of the Jack the Ripper suspects; this theory has been dismissed, because he would have been unable to return to Cambridge in time for lectures the following morning. Stephen’s poem The Old School List from Quo Musa Tendis is included in the front pages of H. E. C. Stapleton’s Eton School Lists 1853-1892, and the author refers to him in the preface as 'an Etonian of great promise, who died only too early for his numerous friends’. During his time at Eton, Stephen was a friend of Harry Goodhart (1858–1895), who became an England international footballer and later a Professor at the University of Edinburgh. Goodhart is referred to as “one of them’s wed” in the last verse of The Old School List: There were two good fellows I used to know. —How distant it all appears! We played together in football weather, And messed together for years: Now one of them's wed, and the other's dead So long that he's hardly missed Save by us, who messed with him years ago: But we're all in the old School List. Collections Select Poems 1926 Augustan Books of Modern Poetry Lapsus Calami JKS Cambridge 1891 Quo Musa Tendis Cambridge 1891 Lapsus Calami and other verses 1896 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Kenneth_Stephen