The Hon. Herbert Asquith (11 March 1881– 5 August 1947) was an English poet, novelist and lawyer. Biography Nicknamed “Beb” by his family, he was the second son of H. H. Asquith, British Prime Minister—with whom he is frequently confused—and younger brother of Raymond Asquith. His wife Lady Cynthia Asquith, whom he married in 1910, the daughter of Hugo Richard Charteris, 11th Earl of Wemyss (1857–1937), was also a writer. Asquith was greatly affected by his service with the Royal Artillery in World War I. His poems include “The Volunteer” and “The Fallen Subaltern”, the latter being a tribute to fallen soldiers; his poem “Soldiers at Peace” was set to music by Ina Boyle. His books include Roon and Young Orland. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Asquith_(poet)

.jpg)

Olga Acevedo (1895–1970) es una poetisa chilena. Vivió algunos años en Punta Arenas donde frecuentó la Sociedad Literaria de Gabriela Mistral. Es descrita como una poetisa auténtica que es sincera a fuerza de sufrir enormemente. Sus vocablos eran audaces pero imprecisos. Se destacó por su estilo moderno pero inclasificable y su obra está impregnada de un temple angustioso y destructivo.

Amenudo solemos callar lo que nuestros labios no pueden hablar,no hay una relación efectiva entre el alma y las palabras no hay forma de poder explicar lo que tu alma grita no hay quien entienda el idioma de un alma agrieta ,la única manera de poder expresar lo que llevamos dentro es cribiendo así lo hicieron los grandes poetas así liberaron la voz de su alma .

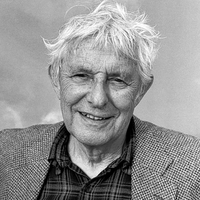

Archie Randolph Ammons (February 18, 1926– February 25, 2001) was an American poet who won the annual National Book Award for Poetry in 1973 and 1993. Preface Ammons wrote about humanity’s relationship to nature in alternately comic and solemn tones. His poetry often addresses religious and philosophical matters and scenes involving nature, almost in a Transcendental fashion. According to reviewer Daniel Hoffman, his work “is founded on an implied Emersonian division of experience into Nature and the Soul,” adding that it "sometimes consciously echo[es] familiar lines from Emerson, Whitman and [Emily] Dickinson.” Life Ammons grew up on a tobacco farm near Whiteville, North Carolina, in the southeastern part of the state. He served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, stationed on board the U.S.S. Gunason, a battleship escort. After the war, Ammons attended Wake Forest University, majoring in biology. Graduating in 1949, he served as a principal and teacher at Hattaras Elementary School later that year and also married Phyllis Plumbo. He received an M.A. in English from the University of California, Berkeley. In 1964, Ammons joined the faculty of Cornell University, eventually becoming Goldwin Smith Professor of English and Poet in Residence. He retired from Cornell in 1998. Ammons had been a longtime resident of the South Jersey communities of Northfield, Ocean City and Millville, when he wrote Corsons Inlet in 1962. Awards * During the five decades of his poetic career, Ammons was the recipient of many awards and citations. Among his major honors are the 1973 and 1993 U.S. National Book Awards (for Collected Poems, 1951-1971 and for Garbage); the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets (1998); and a MacArthur Fellowship in 1981, the year the award was established. A school in Miami, Florida, was named after him. * Ammons’s other awards include a 1981 National Book Critics Circle Award for A Coast of Trees; a 1993 Library of Congress Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry for Garbage; the 1971 Bollingen Prize for Sphere; the Poetry Society of America’s Robert Frost Medal; the Ruth Lilly Prize; and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1978. Poetic style * Ammons often writes in two– or three-line stanzas. Poet David Lehman notes a resemblance between Ammons’s terza libre (unrhymed three-line stanzas) and the terza rima of Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind.” Lines are strongly enjambed. * Some of Ammons’s poems are very short, one or two lines only, a form known as monostich (effectively, including the title, a kind of couplet), while others (for example, the book-length poems Sphere and Tape for the Turn of the Year) are hundreds of lines long, and sometimes composed on adding-machine tape or other continuous strips of paper. His National Book Award-winning volume Garbage is a long poem consisting of “a single extended sentence, divided into eighteen sections, arranged in couplets”. Ammons’s long poems tend to derive multiple strands from a single image. * Many readers and critics have noted Ammons’s idiosyncratic approach to punctuation. Lehman has written that Ammons “bears out T. S. Eliot’s observation that poetry is a 'system of punctuation’.” Instead of periods, some poems end with an ellipsis; others have no terminal punctuation at all. The colon is an Ammons “signature”; he uses it “as an all-purpose punctuation mark.” * The colon permits him to stress the linkage between clauses and to postpone closure indefinitely.... When I asked Archie about his use of colons, he said that when he started writing poetry, he couldn’t write if he thought “it was going to be important,” so he wrote "on the back of used mimeographed paper my wife brought home, and I used small [lowercase] letters and colons, which were democratic, and meant that there would be something before and after [every phrase] and the writing would be a kind of continuous stream." * According to critic Stephen Burt, in many poems Ammons combines three types of diction: * A “normal” range of language for poetry, including the standard English of educated conversation and the slightly rarer words we expect to see in literature (“vast,” “summon,” “universal”). * A demotic register, including the folk-speech of eastern North Carolina, where he grew up (“dibbles”), and broader American chatter unexpected in serious poems (“blip”). * The Greek– and Latin-derived phraseology of the natural sciences (“millimeter,” “information of actions / summarized”), especially geology, physics, and cybernetics. * Such a mixture is nearly unique, Burt says; these three modes are “almost never found together outside his poems”. Works * * Poetry * Ommateum, with Doxology. Philadelphia: Dorrance, 1955. * Expressions of Sea Level. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1964. * Corsons Inlet. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1965. Reprinted by Norton, 1967. ISBN 0-393-04463-7 * Tape for the Turn of the Year. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1965. Reprinted by Norton, 1972. ISBN 0-393-00659-X * Northfield Poems. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1966. * Selected Poems. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1968. * Uplands. New York: Norton, 1970. ISBN 0-393-04322-3 * Briefings: Poems Small and Easy. New York: Norton, 1971. ISBN 0-393-04326-6 * Collected Poems, 1951-1971. New York: Norton, 1972. ISBN 0-393-04241-3—winner of the National Book Award * Sphere: The Form of a Motion. New York: Norton, 1974. ISBN 0-393-04388-6—winner of the Bollingen Prize for Poetry * Diversifications. New York: Norton, 1975. ISBN 0-393-04414-9 * The Selected Poems: 1951-1977. New York: Norton, 1977. ISBN 0-393-04465-3 * Highgate Road. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1977. * The Snow Poems . New York: Norton, 1977. ISBN 0-393-04467-X * Selected Longer Poems. New York: Norton, 1980. ISBN 0-393-01297-2 * A Coast of Trees. New York: Norton, 1981. ISBN 0-393-01447-9—winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award * Worldly Hopes. New York: Norton, 1982. ISBN 0-393-01518-1 * Lake Effect Country. New York: Norton, 1983. ISBN 0-393-01702-8 * The Selected Poems: Expanded Edition. New York: Norton, 1986. ISBN 0-393-02411-3 * Sumerian Vistas. New York: Norton, 1987. ISBN 0-393-02468-7 * The Really Short Poems. New York: Norton, 1991. ISBN 0-393-02870-4 * Garbage. New York: Norton, 1993. ISBN 0-393-03542-5—winner of the National Book Award * The North Carolina Poems. Alex Albright, ed. Rocky Mount, NC: NC Wesleyan College P, 1994. ISBN 0-933598-51-3 * Brink Road.New York: Norton, 1996. ISBN 0-393-03958-7 * Glare. New York: Norton, 1997. ISBN 0-393-04096-8 * Bosh and Flapdoodle: Poems. New York: Norton, 2005. ISBN 0-393-05952-9 * Selected Poems. David Lehman, ed. New York: Library of America, 2006. ISBN 1-931082-93-6 * The North Carolina Poems. New, expanded edition. Frankfort, KY: Broadstone Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9802117-2-6 * The Mule Poems. Fountain, NC: R. A. Fountain, 2010. ISBN 0-9842102-0-2 (chapbook) * Prose * Set in Motion: Essays, Interviews, and Dialogues (1996) * An Image for Longing: Selected Letters and Journals of A.R. Ammons, 1951-1974. Ed. Kevin McGuirk. Victoria, BC: ELS Editions, 2014. ISBN 978-1550584561 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._R._Ammons

Juan Almeida Bosque (La Habana, Cuba, 17 de febrero de 1927 – La Habana, 11 de septiembre de 2009 ) fue un político, militar y compositor cubano. Juan Almeida está considerado como la tercera figura más relevante del poder cubano después de Fidel Castro y su hermano Raúl Castro. Integrante de la lucha contra la dictadura de Fulgencio Batista comenzó su actividad revolucionaria en 1952 participando en el asalto al cuartel Moncada en 1953. Destacó en las luchas revolucionarias después del desembarco del Granma destacando en ellas. Después del triunfo de la Revolución el 1 de enero de 1959, Almeida tuvo numerosas responsabilidades. Formó parte del Buró Político del Comité Central del Partido desde su fundación en 1965 siendo ratificado en todos los congresos. Fue elegido diputado para la Asamblea Nacional y Vicepresidente del Consejo de Estado, desde la primera legislatura del Parlamento cubano del nuevo periodo que se abrió tras el primero de enero de 1959. Fue comandante de la Revolución y presidente de la Asociación de Combatientes de la Revolución Cubana. En su faceta de compositor y escritor realizó más de 300 canciones y una docena de libros. Labor revolucionaria inicial Participó en la lucha por el golpe de estado del 10 de marzo de 1952 donde conoció a Fidel Castro, al cual sigue posteriormente en el asalto al Cuartel Moncada el 26 de julio de 1953. Es condenado a prisión a consecuencia de este asalto por un período de 10 años; en 1955 fue amnistiado junto a sus compañeros. Expedicionario del yate Granma en 1956. El 27 de febrero de 1958 fue ascendido a Comandante del Ejército Rebelde y pasó a dirigir la columna Santiago de Cuba. Del III Frente Oriental hacia el Triunfo de la Revolución Fue uno de los Comandantes del Ejército Rebelde durante la lucha en la Sierra Maestra En marzo de ese mismo año dirigió III Frente Oriental Dr. Mario Muñoz Monroy, el cual inicialmente adopta el nombre de III Frente de Operaciones en la Sierra Maestra. Tras el triunfo de la revolución (1959) pasó a ocupar cargos en las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias (FAR). Figura política en el gobierno revolucionario El 29 de marzo de 1962, Juan Almeida participa como Vocal del Tribunal Revolucionario presidido por el comandante Augusto Martínez Sánchez que se encargó de enjuiciar en juicio sumarísimo a los participantes de la Invasión de Bahía de Cochinos el 17 de abril de 1961. Este tribunal lo integraban además los comandantes Guillermo García Frías, Sergio del Valle y Manuel Piñeiro. Fue elegido miembro del Comité Central del Partido Comunista de Cuba y de su Buró Político en octubre de 1965. Es diputado a la Asamblea Nacional del Poder Popular desde la primera legislatura y Vicepresidente del Consejo de Estado de Cuba. Presidente de la Asociación de Combatientes de la República de Cuba. Junto a sus responsabilidad como presidente de la dirección nacional de la Asociación de Combatientes de la Revolución Cubana (ACRC). La ACRC es la organización que rige el trabajo de los veteranos de las guerras y de los militares de avanzada edad que se comprometen con los principios del Estado cubano. Trayectoria artística Su legado va más allá de la lucha revolucionaria pues incursionó en el arte como escritor y como compositor musical. Además compuso más de trescientas canciones de las cuales se han hecho varias producciones discográficas, dos de sus canciones más populares son La Lupe y Dame un traguito. Fallecimiento. El día 11 de septiembre de 2009 a las 23:30, hora cubana, falleció debido a un paro cardiorrespiratorio a la edad de 82 años. Sus restos mortales fueron sepultados en el mausoleo del III Frente Oriental, en Santiago, junto a otros combatientes de la Revolución Cubana. Condecoraciones recibidas * Título Honorífico de Héroe de la República de Cuba. * Orden Máximo Gómez de primer grado (otorgada el 27 de febrero de 1998, en ocasión del aniversario 40 de su ascenso a Comandante en la Sierra Maestra). Obras * Presidio * Exilio * Desembarco * La Sierra * Por las faldas del Turquino * Contra el Agua y el Viento, Premio Casa de las Américas (1985) * La Única Ciudadana * El General en Jefe Máximo Gómez * ¡Atención! ¡Recuento! * La Sierra Maestra y más Allá * Algo nuevo en el desierto * La Aurora de los héroes Referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Almeida_Bosque

Nací en la Ciudad de Ica,en 1961,allá en el campo al sur de la ciudad crecí como todos los niños de mi época,jugando entre las hiervas y los sembríos de la pequeña parcela y la de los hacendados,me nutrí del paisaje amplio y verde varíopinto ,de su mágica belleza y su espléndida cosecha,me hice a la mar ya a mis años mozos y al crepúsculo desde que nací,mis manos modelaron siempre la plástica arcilla que arranque del vientre de mi tierra natal y mis manos pintaron los paisajes que la primavera pusieron a mi vista en los años buenos y logre arrancar belleza a lo agreste y moribundo con otoñal ternura y guarde en mi mente todo aquello que vi,para dárselo a mi pluma en mis horas solitarias,en donde solo soñé,existí y escribí con total libertad.Mis estudios fueron en la escuelita rural y de allí me mude a la de primaria de la gran ciudad,entre pelos lengua y malas tintas llegue a la secundaria de mala gana me fui al experimental colegio Abrahám Valdelomar,nunca me aficione a las ciencias,hasta después de haber conocido la obra de Julio Verne,de haber dormido con el Quijote de la Mancha y llorado con Platero y Yo;me adentre con gran pasión en el mágico mundo de las letras y arte en su total dimensión en donde me he perdido para la humanidad por que hoy solo vivo para el arte.Mis estudios Superiores en La Escuela Nacional Superior Autónoma de Bellas Artes del Perú en la Capital Lima me nutrieron de la técnica y disciplina,y forjaron mi sentido estético,mi moral y mi fuerza espiritual para seguir existiendo y viviendo por el arte,para el arte y con el arte con total libertad.

Auguste Angellier, né le 1er juillet 1848 à Dunkerque et mort le 28 février 1911 à Boulogne-sur-Mer est un poète et universitaire français, qui fut le premier professeur de langue et littérature anglaises de la Faculté des lettres de Lille, avant d'en être son doyen de 1897 à 1900. Critique et historien de la littérature, il fit sensation à la Sorbonne en attaquant les théories d'Hippolyte Taine dans sa thèse sur Robert Burns en 1893. Biographie Né le 1er juillet 1848 à Dunkerque (Nord), d'un père maître-plafonnier et d'une mère secrétaire, Auguste Angellier fut scolarisé à Boulogne-sur-Mer où sa mère l'emmène après s'être séparée de son mari en 1853. Son attachement à cette ville ne se démentit jamais. Jeune homme, il prépare le concours de l'École normale supérieure au Lycée Louis-le-Grand de Paris en 1866. Entre l'écrit et l'oral du concours, il est expulsé du lycée par le censeur qui le considère, à tort selon certains, comme le chef d'un mouvement de révolte concernant la mauvaise qualité de la nourriture à la cantine. Cet épisode catastrophique de sa vie scolaire le pousse à partir, par manque de moyens financiers, pour l'Angleterre où on lui offre un emploi d'enseignant dans un petit pensionnat. Engagé volontaire au cours de la guerre de 1870, il se retrouve à Lyon puis à Bordeaux. Une infection respiratoire grave le fait rentrer à Paris, pendant la Commune, et, la guerre terminée, il est nommé répétiteur en 1871 au Lycée Louis-Descartes (il avait été enfin autorisé à rentrer dans le giron de l’Instruction publique). Il décroche sa licence peu après. Reçu au certificat d’aptitude à l’enseignement de l’anglais, deux ans plus tard, il professe en tant que « maître-répétiteur » pendant trois ans, période exigée à l’époque avant de pouvoir s’inscrire à l’agrégation. Il obtient ce concours à 28 ans, et enseigne aussitôt au lycée Charlemagne, jusqu’à son départ en Angleterre en 1878. Angellier cultive de nombreuses amitiés littéraires, et développe sa sensibilité de poète (sa notoriété lui viendra davantage de son travail universitaire que de son œuvre poétique). Jusqu’à cette période, il hésite entre le journalisme et l’enseignement, mais le congé qui vient de lui être accordé lui permet de s’intéresser au projet de réforme des études de langues vivantes en France (à travers l’étude du fonctionnement des universités anglaises). C’est avec plaisir qu’il s’éloigne un moment de la lourdeur administrative qui lui pèse tant dans sa fonction d’enseignant. En 1881, un poste de maître de conférences, à Douai, lui ouvre une brillante carrière de professeur d’anglais (la faculté des Lettres de Douai va être transférée à Lille en 1887). Douze années plus tard, il soutient ses deux thèses, chacune consacrée à un poète : la « majeure » à l’Écossais Robert Burns, et la thèse complémentaire à John Keats, thèse rédigée en latin ! Le titre de cette dernière : De Johannis Keatsii, vita et Carminibus ; son auteur : Augustus Angellier, literarum doctor in Universitate Insulensi Professor. Même les citations des poèmes de Keats sont en latin (et l’université dont il est question n’est autre que celle de Lille : Universitate Insulensi). Dès lors, Angellier porte le titre de Professeur. De plus, il assure la fonction de président du jury d’agrégation d’anglais de 1890 à 1904 ; et dès février 1897, il assume la tâche de doyen, et les lourdes responsabilités administratives qui s’y attachent. En 1902, détachement (sur un poste de maître de conférences) à l’École normale supérieure, puis retour à Lille en 1904. Auguste Angellier est mort à 62 ans, le 28 février 1911, à Boulogne-sur-Mer. Œuvres En 1896, Angellier le poète a publié À l’amie perdue (178 sonnets inspirés par le chagrin de son histoire d'amour cachée avec Thérèse Fontaine1), et en 1903, Le chemin des saisons. D’autres œuvres suivent : Dans la lumière antique, deux livres de Dialogues et deux d’Épisodes. Curiosité Le compositeur polonais Henryk Opieński (1870-1942) qui dirigeait à Morges (Suisse) l'ensemble Motet et Madrigal a écrit une œuvre pour chœur à 4 voix d'hommes sur le texte poétique La Fuite de l'Hiver qui fait partie du recueil Le chemin des saisons d'Auguste Angellier. Les références Wikipedia – https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auguste_Angellier

Ludovico Ariosto (Reggio nell’Emilia, 8 settembre 1474 – Ferrara, 6 luglio 1533) è stato un poeta, commediografo, funzionario e diplomatico italiano, autore dell’Orlando furioso (1516-1521-1532). È considerato uno degli autori più celebri ed influenti del suo tempo. Le sue opere, il Furioso in particolare, simboleggiano una potente rottura degli standard e dei canoni dell’epoca. La sua ottava, definita “ottava d’oro”, rappresenta uno dei massimi della letteratura pre-illuminista. Biografia Ludovico Ariosto nacque a Reggio Emilia l’8 settembre del 1474, primo di dieci fratelli. Suo padre Niccolò, proveniente dalla nobile famiglia degli Ariosti, faceva parte della corte del duca Ercole I d’Este ed era comandante del presidio militare degli Estensi a Reggio Emilia. La madre, Daria Malaguzzi Valeri, era una nobildonna di Reggio.Ludovico dapprima intraprese, per volontà del padre, studi di legge a Ferrara, ma li abbandonò dopo poco tempo per concentrarsi pienamente negli studi umanistici sotto la guida del monaco agostiniano Gregorio da Spoleto. Ariosto seguì nel frattempo studi di filosofia presso l’Università di Ferrara, appassionandosi così anche alla poesia in volgare. Il fatto che il padre fosse funzionario della corte degli Estensi gli permise, fin dalla giovane età, di avere contatti con il mondo della corte, luogo della sua formazione letteraria e umanistica. Divenuto amico di Pietro Bembo, condivise con lui l’entusiasmo e la passione per le opere di Petrarca. Alla morte del padre, nel 1500, Ludovico si ritrovò a dover badare alla famiglia; nel 1502 si vide “costretto” ad accettare l’incarico di capitano della rocca presso Canossa ed è proprio qui che, da Maria, domestica che già aveva servito il padre, gli nasce Giambattista, il primogenito che Ludovico non sarà mai completamente convinto di dover riconoscere come proprio, contestando l’affidabilità di Maria. Successivamente, rientrato a Ferrara, non ancora trentenne diviene funzionario e viene assunto dal cardinale Ippolito d’Este (figlio di Ercole), per ottenere alcuni benefici ecclesiastici, facendosi poi chierico. Nel 1506 fu investito del beneficio della ricca parrocchia di Montericco (ora frazione di Albinea, in provincia di Reggio Emilia). Questa condizione gli spiacque molto: Ippolito era uomo avaro, ignorante e gretto; Ariosto stesso era divenuto un umile cortigiano, un ambasciatore, un “cavallaro”. Potrebbe meravigliare che l’Ariosto fosse addirittura “ cameriere “ alle dipendenze del Cardinale: in realtà questo termine deve essere inteso come cameriere segreto o come cameriere d’onore. In questo periodo, quindi, a causa delle faccende diplomatiche e politiche di cui doveva occuparsi, non ebbe tempo di dedicarsi alla letteratura. Nel 1509, a Ferrara, da un’altra domestica di casa Ariosto, Orsolina di Sassomarino, gli nasce un altro figlio, Virginio, che verrà poi legittimato e che seguirà le orme del padre. Il legame con Orsolina durò vari anni e fu importante per il poeta, che comprò alla madre del suo secondogenito una casa nella strada di San Michele, poi via del Turco. Nel 1513, dopo la morte del papa Giulio II della Rovere, venne eletto papa Leone X (Giovanni dei Medici), che aveva spesso manifestato stima e amicizia nei confronti dell’Ariosto. Il poeta considerava Roma il centro culturale italiano per eccellenza e decise così di recarsi alla curia papale con la speranza di trasferirvisi dopo aver ottenuto un incarico, ma invano. Intanto a Firenze Ariosto si innamorò di una donna, Alessandra Benucci, moglie del mercante Tito Strozzi, che frequentava la corte estense per affari. Successivamente, dopo essere rimasta vedova nel 1515, la donna si trasferì a Ferrara, iniziando una relazione con lo scrittore. L’Ariosto era stato sempre restio al matrimonio; pertanto si sposò solo dopo anni, in gran segreto per la paura di perdere i benefici ecclesiastici che gli erano stati concessi e con lo scopo di evitare che alla donna venisse revocata l’eredità del marito.Nel 1516 pubblicò la prima edizione dell’Orlando furioso, poema diviso in 40 canti, la cui stesura era iniziata 11 anni prima della pubblicazione. Lo dedicò al suo signore, il quale non lo apprezzò affatto. Quando nel 1517 Ippolito d’Este divenne vescovo di Agria (nome italiano per Eger, nell’Ungheria orientale), Ludovico si rifiutò di seguirlo, adducendo motivi di salute. In realtà le cause sono da ricercare nell’astio verso il cardinale, nell’amore per la sua Ferrara e in quello per la sua donna. Passò quindi al servizio di Alfonso. Anche questa si trattava di «servitù», ma «di minor disagio e probabilmente era più dignitosa». Nel 1522 Alfonso gli affidò l’arduo compito di governatore della Garfagnana, da poco annessa al Ducato, regione turbolenta, abitata da una popolazione fiera ed indomita poco avvezza al comando ed infestata da banditi, in cui l’ordine doveva essere mantenuto con la forza; in quest’occasione Ariosto dimostrò abilità politiche e pratiche. Pure queste attività gli erano invise perché gli impedivano di dedicarsi agli studi ed alla poesia. Dal 1525 tornò a Ferrara e passò i suoi ultimi anni tranquillamente, dedicandosi alla scrittura e alla messa in scena di alcune commedie e all’ampliamento dell’Orlando furioso. Rifiutò l’incarico di ambasciatore papale, spiegando che desiderava occuparsi delle sue opere e della famiglia.Nel 1532 Ariosto accompagnò Alfonso all’incontro a Mantova con l’imperatore Carlo V; al rientro a Ferrara, si ammalò di enterite e morì, dopo alcuni mesi di malattia, il 6 luglio 1533. Ludovico fu sepolto dapprima nella chiesa di San Benedetto a Ferrara e successivamente venne tumulato con grandi onori a Palazzo Paradiso. Il suo monumento funebre è opera dello scultore mantovano Alessandro Nani su disegno dell’architetto Giovan Battista Aleotti. Personalità Ariosto nelle sue opere lascia di sé l’immagine di uomo amante della vita sedentaria, tranquilla, scevra di atteggiamenti eroici.In realtà si tratta di un’immagine letteraria, di «una scelta matura e meditata». Per dovere o per scelta, egli viaggiò molto e dimostrò anche notevoli doti pratiche. Si è di fronte all’ultimo grande umanista e alla crisi dell’Umanesimo: Ariosto rappresenta ancora l’uomo nuovo che si pone al centro del mondo, il demiurgo che con l’arte plasma la realtà fantastica, ma non lo è nella sua vita sociale di umile cortigiano subordinato alla volontà di un signore. Opere Poesia lirica La produzione lirica di Ariosto viene suddivisa in due filoni: latino e volgare. Il primo degli anni della giovinezza comprende sessantasette opere ed ha importanza documentaria. Il secondo è formato da dieci opere originali ed importanti.Complessivamente la produzione lirica ariostesca comprende ottantasette componimenti (sonetti, madrigali, canzoni, egloghe e capitoli in terza rima). Le opere, non raccolte in un canzoniere organico, vennero pubblicate solo postume nel 1546. Ariosto viene influenzato dal modello petrarchesco riproposto dall’amico Pietro Bembo. Da questa scelta deriva la ricerca meticolosa del lessico e della metrica e la rilevanza del tema dell’amore.Risulta interessante la sua reinterpretazione umanistica. Mentre Bembo si discosta poco dai dettami petrarcheschi Ariosto li adatta ai canoni dell’Umanesimo, riferendosi costantemente ai classici latini come Tibullo, Properzio, Catullo e Orazio. Orlando furioso L’Orlando furioso è un poema cavalleresco in ottave, a schema ABABABCC, strutturato su 46 canti, per un totale di 38.736 versi nell’edizione definitiva del 1532. Vi sono state infatti due edizioni precedenti, scritte con una lingua più popolare e rozza. In particolare, una prima redazione dell’Orlando furioso, in 40 canti, era stata redatta nel 1515 e venne pubblicata nel 1516. La seconda edizione uscì nel 1521, caratterizzata da una lieve revisione linguistica.L’opera ha una trama molto stratificata che si sviluppa sostanzialmente su tre narrazioni principali: quella militare, costituita dalla guerra tra i paladini, difensori della religione cristiana, e i Saraceni infedeli; quella amorosa, incentrata sulla fuga di Angelica e sulla pazzia di Orlando, e infine quella encomiastica, con cui si lodava la grandezza dei duchi d’Este, dedicata invece alle vicende amorose tra la cristiana Bradamante e il saraceno Ruggiero.L’Orlando furioso si propone come il naturale prosieguo dell’Orlando innamorato di Matteo Maria Boiardo; Ariosto continuò la narrazione proprio dove Boiardo la interruppe, facendo evolvere la vicenda amorosa tra Angelica e Orlando che, a causa del rifiuto dell’amata, diviene furioso, pazzo per amore.La lingua definitiva dell’Orlando furioso è ben diversa da quella delle edizioni precedenti. In principio il registro linguistico, ricco di termini toscani, padani e latineggianti, teneva conto delle espressività popolari, essendo più orientato a un pubblico ferrarese o padano. Fu solo dopo che Ariosto si rese conto della portata di capolavoro dell’opera si mirò a creare un modello linguistico italiano nazionale, secondo i canoni teorizzati da Pietro Bembo nelle sue Prose della volgar lingua. La revisione tuttavia non riguarda soltanto l’aspetto linguistico e stilistico, ma anche i contenuti: vi è l’aggiunta di diversi episodi significativi come quello di Olimpia (canti IX-XI) e soprattutto di Marganorre (XXXVII) fino a raggiungere l’attuale struttura di 46 canti. L’inserimento di questi episodi provocò anche una variazione degli equilibri strutturali. Infatti, l’episodio di Marganorre, feroce tiranno persecutore delle donne, funge da contrappeso a quello delle femmine omicide. Uno degli obiettivi di Ariosto è quello di invitare il lettore ad una riflessione sul reale. Uno dei procedimenti volti a questo è quello dello straniamento, che consiste in un cambiamento della prospettiva in modo da guardare l’argomento trattato con imparzialità, impedendo al lettore l’immedesimazione emotiva e invogliandolo ad un atteggiamento critico. Un simile effetto avviene soprattutto grazie all’intervento della voce narrante nel corso della narrazione. Ad esempio, nel I canto, quando Angelica afferma avanti a Sacripante di essere ancora vergine, la voce narrante commenta: «Forse era ver, ma non però credibile / a chi del senso suo fosse signore; / ma parve facilmente a lui possibile, / ch’era perduto in via più grave errore» Un commento del genere, inevitabilmente, costringe a riflettere sull’ambiguità dei personaggi e su ciò a cui si sta assistendo. Sempre volto alla riflessione sul reale, è il procedimento dell’abbassamento, consistente nell’abbassare appunto la dignità eroica dei suoi personaggi, riportandoli ad un livello comune e quotidiano. Evento maggiormente significativo è quando Orlando si rende conto dell’amore di Angelica con Medoro e il suo letto gli pare «più duro ch’un sasso, e più pungente / che se fosse d’urtica»: l’ortica ovviamente non rende grazie al personaggio di Orlando, tanto acclamato nella precedente generazione, ora viene, volutamente e non per semplice gioco parodico, svilito per riflettere sul comportamento degli uomini. Satire Le Satire sono l’opera ariostesca più apprezzata dalla storia dopo il Furioso. Si tratta di sette componimenti in terzine, scritti in forma di lettere indirizzate da Ariosto a parenti e amici realmente esistiti, plasmate secondo i canoni delle satire latine e in particolar modo secondo i canoni oraziani.I temi principali delle Satire riguardano la condizione dell’intellettuale cortigiano, il contrasto fra questa condizione e il desiderio di libertà personale, l’aspirazione ad una vita dedita allo studio lontana dall’avidità della corte e dalla corruzione della politica. L’atteggiamento di Ariosto è sì ironico, ma sempre pacato e tollerante, senza mai dar vita a situazioni polemiche. Questo non va confuso con un disinteresse nei confronti della realtà; al contrario, testimonia la sua capacità di osservazione, ottenuta dopo importanti esperienze personali in campo politico, seppur compiute controvoglia .Le Satire rappresentano in tutto e per tutto una pietra miliare della letteratura ariostesca e rinascimentale in genere, in quanto è apprezzabile quell’atteggiamento riflessivo, tanto caro ai letterati post 1494, che è sì presente anche nell’Orlando furioso, ma che appare in maniera più evidente grazie all’assenza della componente fiabesca e fantastica. Commedie * Di seguito vengono riportate le commedie prodotte da Ariosto: * La tragedia di Tisbe, perduta, 1493 (trattandosi di una tragedia di ispirazione ovidiana, sarebbe piuttosto da inserire in una più generica categoria dei testi drammatici); * La Cassaria, in prosa, 1508; * I Suppositi, in prosa, 1509; * Il Negromante, in versi, 1520; * La Lena, in versi, 1528; * Gli studenti, incompiuta, in versi, 1518-19. Riferimenti Wikipedia – https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludovico_Ariosto

1886-1919 Claudio de Alas: la verdadera historia del último y único poeta maldito colombiano Por Francis Oliverio Recúpero “Aunque pueda parecer una paradoja (y las paradojas siempre son peligrosas), no por eso es menos cierto que la vida imita al arte mucho más de lo que el arte imita a la vida”—Oscar Wilde, “La decadencia de la mentira” Por esos pequeños milagros que la vida a veces nos regala, llegó a mis manos un libro llamado “El Cansancio de Claudio de Alas” Con suma atención me puse a leer sus poesías, y quedé subyugado, maravillado con este poeta colombiano que escribió, hace cien años, versos como éstos: “Con la santa impudicia de una estatua desnuda este Libro sonoro, doy al vértigo humano: fue sentido en la Muerte, el Pecado y la Duda y con sangre del alma, lo escribí con mi mano” ¿Quién fue Claudio de Alas? Juan José de Soiza Reilly, compilador testamentario de Jorge Escobar Uribe –tal era el nombre verdadero de de Alas- nos cuenta que el poeta nació a fines del siglo dieciocho en el seno de una familia de la élite colombiana; de adolescente se hizo revolucionario y luego de pelear en guerras civiles abandonó su patria, viviendo en Ecuador, Perú y Chile. Fue en este último país donde alcanzó la fama en los Juegos Florales que ganó Gabriela Mistral con los "Sonetos de la muerte" en 1914, donde obtuvo una mención con un "Salmo de amor" en castellano medieval. Pero él pensaba que “triunfar en Buenos Aires era la gloria más hermosa a que puede aspirar un poeta”, y vino. “No leáis este libro! –que es satánico y triste- ¡No leáis este Libro! Que el infierno en él zumba- No leáis este libro –que lloró lo que existe-“ Sin embargo, cuando el compilador conoció al poeta y éste le contó su deseo de triunfar en estas tierras, le advirtió: —Vea amigo, si usted quiere triunfar, váyase hoy mismo. Huya. Vuele. Aquí nadie triunfa. Aquí sobrevivimos. Nada más. No le hizo caso nuestro poeta y se dedicó al ejercicio del periodismo con discreto éxito. Un pintor inglés lo alojó en su casona de Bánfield “hasta que encuentres quien te pague mejor” Allí escribía, leía y traducía a su querido Oscar Wilde, y siempre lo acompañaba un viejo perro que vivía con el pintor. El 5 de marzo de 1918 de Alas se suicidó en la casa de su amigo. Nos cuenta su compilador: “Los 32 años de edad que tenía le pesaban como si hubiera vivido siempre en la opulencia…Atardecía…Encerróse en su habitación. Lloró sobre estos pobres papeles floridos de versos y escribió tres cartas” Una fue para su hermano, otra para el pintor que lo hospedaba y la última para un amigo a quien le cuenta ese “dolor enorme de sentirse solo ante la vida implacablemente hostil” Como cumpliendo un extraño pacto de amistad, primero mató al viejo perro que lo había adoptado. Y el segundo balazo fue para él mismo. En voz baja Qué garra de tristeza, la que a mi Ser tortura, Al verme cual un paria de todos olvidado… Sin unos dulces ojos que miren mi amargura, Ni besos que reanimen mi espíritu cansado. La noche me hace muecas como de sepultura, Cuando me rindo al duelo del hogar alquidado: Todo es allí egoísta y encierra la pavura De lo que no nos ama, ni que nos es amado. No encontrar unos brazos de mujer, que me ciñan, Ni una boca de fiebre, ni unas divinas ancas… No escuchar esas frases que arrullen o que riñan!... ¡Oh,Corazón, detente! Porque al latir arrancas Los hierros del suplicio, que anhelo te constriñan, Para que no solloces ante unas manos blancas. Cuando todos pensaban que se había matado por no triunfar en Buenos Aires, su amigo pintor echó luz sobre el final de de Alas: “¿Sabe usted por qué se mató Claudio?...porque sabía mucho….Se mató porque su cerebro había profundizado la vida y poseía tan hondos conocimientos psicológicos, que se aislaba de la multitud para no hacer notar su diferencia de estatura…Vivía con los libros. Como Oscar Wilde, Claudio no había nacido para las reglas. Había nacido para las excepciones…” Callada y sigilosamente me asesina La espantable seguridad De que yo seré un loco…! En el terror de mi espíritu camina Y la Sombra y la Muerte en mí convoco… La noche me da miedo…Su soledad Alza mil garras que me estrechan… Por qué me gusta de Alas * Porque vivió y murió como un auténtico poeta maldito * Porque le gustaba comer, beber y el sexo en una época en que pecado y placer parecían sinónimos ("lo que es interesante no es nunca correcto" * Porque escribió sobre temas escabrosos, desagradables cumpliendo la máxima baudeleriana de “no confundir las buenas costumbres con el arte” * Porque era moreno * Porque poca gente lo recuerda (ni siquiera Wikipedia) * Porque era colombiano * Porque el municipio de Lomas de Zamora (donde quedaba la casa del pintor) decidió homenajearlo poniendo su nombre a una calle oscura y peligrosa como él, detalle que hubiera sido genial de conocer los homenajeadores algo de la vida y la muerte del poeta, en lugar de dedicarle la única callejuela disponible... * Porque nosotros también hemos sentido ese “dolor enorme de sentirse solo ante la vida implacablemente hostil” * ¡Porque mezclaba el sexo y el amor con la religión!: Una historia terrible Sor Lyrio era una monja de lánguida mirada con formas pubescentes y una blancura astral: Sor Lyrio dirigía, piadosa y resignada, la "Sala de San Bruno" en un viejo hospital… Su blanca mano suave, era solicitada por todos los enfermos, para aliviar su mal... porque Sor Lyrio era, como una iluminada, que retrataba el cielo en su carita oval. Su historia, era una historia de todos ignorada: pero las malas lenguas corrian el rumor… de que estaba entre monjas por cuitas de amor. Sor Lyrio de esas cosas no dijo nunca nada; pero amorosa historia tenía Ella guardada, pues al oír los dichos, prendíase en rubor. II Y sucedió que un día -enfermo y macilento- a la “Sala San Bruno” un buen poeta entró: y era joven, tan dulce, lleno de sentimiento, que a la santa Sor Lyrio el alma cautivó... Después de algunos días tuvo el presentimiento de algo inmotivado, que la ruborizó; pero a pesar de todo, con cariñoso tiento, como a ningún enfermo, Sor Lyrio lo cuidó. Tan milagrosas fueron sus manos de alabastros; tanto su santa boca a Dios lo encomendó, que prodigiosamente el bardo mejoró. Pero las malas lenguas, que siempre buscan rastros, murmuran que Sor Lyrio, en una noche de astros, por su piedad vencida, con el poeta huyó... Anatema Las monjas desde entonces, refiere el pecado diciendo que el poeta era un endemoniado... ¡Embajador del Diablo! ¡Espíritu del mal! Y agregan que Sor Lyrio se encuentra condenada... ¡Pero en la faz de todas surge una llamarada si algún poeta enfermo penetra al hospital. * Porque algunas de sus pinturas parecen tangos brutales: Carne viva Es bella, es rubia, es turbadora, es alta: Bebe champagne y fuma cigarrillos; Y si del mórbido automóvil salta, La pantorrilla ostenta y sus anillos. Al hablar del amor, vibra y se exalta; Cual si esgrimiera lúbricos cuchillos; Y es su marido un hombre que resalta Entre los viejos castos y sencillos… Al casarse con él, era una llama, Que encendida con vicios solitarios, Hizo del goce turbulento drama… Y, hoy van unidos: como dos calvarios: Él un buey manso, que el placer no ama, Y ella, a su diestra, sin amor ni ovarios… * Porque Buenos Aires lo mató (conmigo no pudo, antes me refugié en Misiones) * Porque no sé si tiene una tumba visitable. * Por todo eso yo, Francis Oliverio Recúpero, el último poeta maldito y único argentino, he tenido el honor de presentarles a un grande verdadero y olvidado: Claudio de Alas. Referencias http://francisoliveriorecupero.blogspot.com.es/2009/12/claudio-de-alas-la-verdadera-historia.html

Estudie Ciencias de la Comunicación en la especialidad de Periodismo y diseño gráfico en la espacialidad de Diseño Editorial. Mi poesía se resume en la plaqueta poética 'El Transcurrir de los Encantos' (2005) y 'Tierra Almohada' (2009) bajo el sello Editorial Casatomada. Formo parte de la editorial 'Cielo Gris Editores'. Para los interesados en diseño editorial, pueden contactarme a: [email protected]. Un servidor.

Concepción Arenal (Ferrol, 31 de enero de 1820-Vigo, 4 de febrero de 1893) fue una experta en derecho, pensadora, periodista, poetisa y autora dramática española encuadrada en el realismo literario y pionera en el feminismo español. Además, ha sido considerada la precursora del trabajo social en España. Perteneció a la Sociedad de San Vicente de Paul, colaborando activamente desde 1859. Defendió a través de sus publicaciones la labor llevada a cabo por las comunidades religiosas en España. Colaboró en el Boletín de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza. A lo largo de su vida y obra denunció la situación de las cárceles de hombres y mujeres, la miseria en las casas de salud o la mendicidad y la condición de la mujer en el siglo XIX, en la línea de las sufragistas femeninas decimonónicas, y las precursoras del feminismo.

Dear reader Beware! These poems are strong. I poured my heart into these verses. They say I'm weird, I'm dark. Dark as f..., sweet deep inside Strongly in love - still after all this time Bukowski girl // movies // literature // music Médicoblasto en proceso UAM-X 2019/ matemática trunca / filósofa de closet / políglota Autoinmune girl: DLE + FM, lordosis, cervical sprain, scoliosis

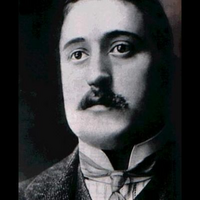

Guillaume Albert Vladimir Alexandre Apollinaire de Kostrowitzky, dit Guillaume Apollinaire, est un poète et écrivain français, critique et théoricien d’art qui serait né sujet polonais de l’Empire russe, le 26 août 1880 à Rome. Il meurt à Paris le 9 novembre 1918 de la grippe espagnole, mais est déclaré mort pour la France en raison de son engagement durant la guerre. Considéré comme l’un des poètes français les plus importants du début du XXe siècle, il est l’auteur de poèmes tels Zone, La Chanson du mal-aimé, Le Pont Mirabeau, ayant fait l’objet de plusieurs adaptations en chanson au cours du siècle. La part érotique de son œuvre– dont principalement trois romans (dont un perdu), de nombreux poèmes et des introductions à des auteurs licencieux– est également passée à la postérité. Il expérimenta un temps la pratique du calligramme (terme de son invention, quoiqu’il ne soit pas l’inventeur du genre lui-même, désignant des poèmes écrits en forme de dessins et non de forme classique en vers et strophes). Il fut le chantre de nombreuses avant-gardes artistiques de son temps, notamment du cubisme et de l’orphisme à la gestation desquels il participa en tant que poète et théoricien de l’Esprit nouveau. Précurseur du surréalisme, avec son drame Les Mamelles de Tirésias (1917), il en forgea le nom. Biographie Jeunesse Guillaume Apollinaire est né à Rome sous le nom de Guglielmo Alberto Wladimiro Alessandro Apollinare de Kostrowitzky, en polonais Wilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Aleksander Apolinary Kostrowicki, herb. Wąż. Apollinaire est en réalité—jusqu’à sa naturalisation en 1916—le 5e prénom de Guillaume Albert Vladimir Alexandre Apollinaire de Kostrowitzky. Sa mère, Angelika Kostrowicka (clan Wąż, ou Angelica de Wąż-Kostrowicky), née à Nowogródek dans le grand-duché de Lituanie, appartenant à l’Empire russe (aujourd’hui Navahrudak en Biélorussie), dans une famille de la petite noblesse polonaise, demeure, après la mort de son père, camérier honorifique de cape et d’épée du pape, à Rome où elle devient la maîtresse d’un noble et a une grossesse non désirée. Son fils est déclaré à la mairie comme étant né le 26 août 1880 d’un père inconnu et d’une mère voulant rester anonyme, de sorte que l’administration l’affubla d’un nom de famille d’emprunt : Dulcigny. Angelika le reconnaît quelques mois plus tard devant notaire comme son fils, sous le nom de Guglielmo Alberto Wladimiro Alessandroi Apollinare de Kostrowitzky. Selon l’hypothèse la plus probable, son père serait un officier italien, Francesco Flugi d’Aspermont. En 1882, elle lui donne un demi-frère, Alberto Eugenio Giovanni. En 1887 elle s’installe à Monaco avec ses fils sous le nom d’Olga de Kostrowitzky. Très vite elle y est arrêtée et fichée par la police comme femme galante, gagnant probablement sa vie comme entraîneuse dans le nouveau casino. Guillaume, placé en pension au collège Saint Charles, dirigé par les frères Maristes, y fait ses études de 1887 à 1895, et se révèle l’un des meilleurs élèves. Puis il est inscrit au lycée Stanislas de Cannes et ensuite au lycée Masséna de Nice où il échoue à son premier baccalauréat et ne se représente pas. Durant les trois mois de l’été 1899, sa mère l’a installé, avec son frère, dans une pension de la petite bourgade wallonne de Stavelot, pension qu’ils quittent, le 6 octobre, à « la cloche de bois » : leur mère ne leur ayant envoyé que l’argent du train, ils ne peuvent payer la note de l’hôtel, et doivent fuir en secret, une fois tout le monde endormi. L’épisode wallon féconde durablement son imagination et sa création. Ainsi, de cette époque date le souvenir des danses festives de cette contrée (« C’est la maclotte qui sautille... »), dans Marie, celui des Hautes Fagnes, ainsi que l’emprunt au dialecte wallon. La mère d’Apollinaire Journal de Paul Léautaud au 20 janvier 1919 : « Je vois entrer une dame [la mère d’Apollinaire, dans le bureau de Léautaud au Mercure de France] assez grande, élégante, d’une allure un peu à part. Grande ressemblance de visage avec Apollinaire, ou plutôt d’Apollinaire avec elle, le nez, un peu les yeux, surtout la bouche et les expressions de la bouche dans le rire et dans le sourire. / Elle me paraît fort originale. Exubérante. Une de ces femmes dont on dit qu’elles sont un peu « hors cadre ». En une demi-heure, elle me raconte sa vie : russe, jamais mariée, nombreux voyages, toute l’Europe ou presque. (Apollinaire m’apparaît soudain ayant hérité en imagination de ce vagabondage.) Apollinaire né à Rome. Elle ne me dit rien du père. / Elle me parle de l’homme avec lequel elle vit depuis vingt-cinq ans, son ami, un Alsacien, grand joueur, tantôt plein d’argent, tantôt sans un sou . Elle ne manque de rien. Dîners chez Paillard, Prunier, Café de la Paix, etc. / Elle me dit qu’elle a plusieurs fois « installé » Apollinaire, l’avoir comblé d’argent. En parlant de lui, elle dit toujours : Wilhelm. / Sentiments féroces à l’égard de la femme d’Apollinaire. / [...] Elle me dépeint Apollinaire comme un fils peu tendre, intéressé, souvent emporté, toujours à demander de l’argent, et peu disposé à en donner quand il en avait. / Elle ne m’a pas caché son âge : 52 ans. Fort bien conservée pour cet âge, surtout élancée et démarche légère, aisée. » À Paris En 1900, il s’installe à Paris, centre des arts et de la littérature européenne à l’époque. Vivant dans la précarité, sa mère lui demande, pour gagner sa vie, de passer un diplôme de sténographie et il devient employé de banque comme son demi-frère Alberto Eugenio Giovanni. L’avocat Esnard l’engage un mois comme nègre pour écrire le roman-feuilleton Que faire ? dans Le Matin, mais refuse de le payer. Pour se venger, il séduit sa jeune maîtresse. En juillet 1901, il écrit son premier article pour Tabarin, hebdomadaire satirique dirigé par Ernest Gaillet, puis en septembre 1901 ses premiers poèmes paraissent dans la revue La Grande France sous son nom Wilhelm Kostrowiztky. De mai 1901 au 21 août 1902, il est le précepteur de la fille d’Élinor Hölterhoff, vicomtesse de Milhau, d’origine allemande et veuve d’un comte français. Il tombe amoureux de la gouvernante anglaise de la petite fille, Annie Playden, qui refuse ses avances. C’est alors la période « rhénane » dont ses recueils portent la trace (La Lorelei, Schinderhannes). De retour à Paris en août 1902, il garde le contact avec Annie et se rend auprès d’elle à deux reprises à Londres. Mais en 1905, elle part pour l’Amérique. Le poète célèbre la douleur de l’éconduit dans Annie, La Chanson du mal-aimé, L’Émigrant de Landor Road, Rhénanes. Entre 1902 et 1907, il travaille pour divers organismes boursiers et parallèlement publie contes et poèmes dans des revues. Il prend à cette époque pour pseudonyme Apollinaire d’après le prénom de son grand-père maternel, Apollinaris, qui rappelle Apollon, dieu de la poésie. En novembre 1903, il crée[réf. nécessaire] un mensuel dont il est rédacteur en chef, Le festin d’Ésope, revue des belles lettres dans lequel il publie quelques poèmes ; on y trouve également des textes de ses amis André Salmon, Alfred Jarry, Mécislas Golberg, entre autres. En 1907, il rencontre l’artiste peintre Marie Laurencin. Ils entretiendront une relation chaotique et orageuse durant sept ans. À cette même époque, il commence à vivre de sa plume et se lie d’amitié avec Pablo Picasso, Antonio de La Gandara, Jean Metzinger, Paul Gordeaux, André Derain, Edmond-Marie Poullain, Maurice de Vlaminck et le Douanier Rousseau, se fait un nom de poète et de journaliste, de conférencier et de critique d’art à L’Intransigeant. En 1909, L’Enchanteur pourrissant, son œuvre ornée de reproductions de bois gravés d’André Derain est publiée par le marchand d’art Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler . Le 7 septembre 1911, accusé de complicité de vol de La Joconde parce qu’une de ses relations avait dérobé des statuettes au Louvre, il est emprisonné durant une semaine à la prison de la Santé ; cette expérience le marque. Cette année-là, il publie Le Bestiaire ou Cortège d’Orphée ornée des gravures de Raoul Dufy. En 1913, les éditions du Mercure de France éditent Alcools, somme de son travail poétique depuis 1898. La guerre En août 1914, il tente de s’engager dans l’armée française, mais le conseil de révision ajourne sa demande car il n’a pas la nationalité française. Lou et Madeleine Il part pour Nice où sa seconde demande, en décembre 1914, sera acceptée, ce qui lancera sa procédure de naturalisation. Peu après son arrivée, un ami lui présente Louise de Coligny-Châtillon, lors d’un déjeuner dans un restaurant niçois. Divorcée, elle demeure chez son ex-belle-sœur à la Villa Baratier, dans les environs de Nice, et mène une vie très libre. Guillaume Apollinaire s’éprend aussitôt d’elle, la surnomme Lou et la courtise d’abord en vain. Puis elle lui accorde ses faveurs, les lui retire et quand il est envoyé faire ses classes à Nîmes après l’acceptation de sa demande d’engagement, elle l’y rejoint pendant une semaine, mais ne lui dissimule pas son attachement pour un homme qu’elle surnommait Toutou. Une correspondance naît de leur relation ; au dos des lettres qu’Apollinaire envoyait au début au rythme d’une par jour ou tous les deux jours, puis de plus en plus espacées, se trouvent des poèmes qui furent rassemblés plus tard sous le titre de Ombre de mon amour puis de Poèmes à Lou. Sa déclaration d’amour, dans une lettre datée du 28 septembre 1914, commençait en ces termes : « Vous ayant dit ce matin que je vous aimais, ma voisine d’hier soir, j’éprouve maintenant moins de gêne à vous l’écrire. Je l’avais déjà senti dès ce déjeuner dans le vieux Nice où vos grands et beaux yeux de biche m’avaient tant troublé que je m’en étais allé aussi tôt que possible afin d’éviter le vertige qu’ils me donnaient. » Mais la jeune femme ne l’aimera jamais comme il l’aurait voulu ; elle refuse de quitter Toutou et à la veille du départ d’Apollinaire pour le front, en mars 1915, ils rompent en se promettant de rester amis. Il part avec le 38e régiment d’artillerie de campagne pour le front de Champagne le 4 avril 1915. Malgré les vicissitudes de l’existence en temps de guerre, il écrit dès qu’il le peut pour garder le moral et rester poète (Case d’Armons), et une abondante correspondance avec Lou, ses nombreux amis, et une jeune fille, Madeleine Pagès, qu’il avait rencontrée dans le train, le 2 janvier 1915, au retour d’un rendez-vous avec Lou. Une fois sur le front, il lui envoie une carte, elle lui répond et ainsi, débute une correspondance vite enflammée qui débouche en août et toujours par correspondance, à une demande en mariage. En novembre 1915, dans le but de devenir officier, Wilhelm de Kostrowitzky est transféré à sa demande dans l’infanterie dont les rangs sont décimés. Il entre au 96e régiment d’infanterie avec le grade de sous-lieutenant puis à Noël, il part pour Oran retrouver sa fiancée pour sa première permission. Il commence aussi, en juillet 1915, une correspondance avec la poétesse Jeanne Burgues-Brun, qui devient sa marraine de guerre. Ces lettres seront publiées en 1948 par les éditions Pour les fils de roi, puis à partir de 1951 par les éditions Gallimard. Le 9 mars 1916, il obtient sa naturalisation française mais quelques jours plus tard, le 17 mars 1916, il est blessé à la tempe par un éclat d’obus. Il lisait alors le Mercure de France dans sa tranchée. Évacué à Paris, il y sera finalement trépané le 10 mai 1916 puis entame une longue convalescence au cours de laquelle il cesse d’écrire à Madeleine. Fin octobre, son recueil de contes, Le Poète Assassiné est publié et la parution est couronnée, le 31 décembre, par un mémorable banquet organisé par ses amis dans l’Ancien Palais d’Orléans. Dernières années En mars 1917, il crée le terme de surréalisme qui apparaît dans une de ses lettres à Paul Dermée et dans le programme du ballet Parade qu’il rédigea pour la représentation du 18 mai. Le 11 mai, il est déclaré définitivement inapte à faire campagne aux armées par la commission médicale et reclassé dans un service auxiliaire. Le 19 juin 1917, il est rattaché au ministère de la guerre qui l’affecte à la Censure. Le 24 juin, il fait jouer sa pièce Les Mamelles de Tirésias (sous-titrée Drame surréaliste en deux actes et un prologue) dans la salle du conservatoire Renée Maubel, aujourd’hui théâtre Galabru. Le 26 novembre, il se dit souffrant et fait prononcer par le comédien Pierre Bertin, sa fameuse conférence L’Esprit Nouveau au théâtre du Vieux Colombier. En 1918, les Éditions Sic publient sa pièce Les Mamelles de Tirésias. Son poème, La jolie rousse, dédié à sa nouvelle compagne, paraît en mars dans la revue L’Éventail. En avril, le Mercure de France publie son nouveau recueil de poésies, Calligrammes. Le 2 mai, il épouse Jacqueline (la « jolie rousse » du poème), à qui l’on doit de nombreuses publications posthumes des œuvres d’Apollinaire. Il a pour témoins Picasso, Gabrièle Buffet et le célèbre marchand d’art Ambroise Vollard. Affecté le 21 mai au bureau de presse du Ministère des Colonies, il est promu lieutenant le 28 juillet. Après une permission de trois semaines auprès de Jacqueline, à Kervoyal (à Damgan, dans le Morbihan), il retourne à son bureau du ministère et continue parallèlement à travailler à des articles, à un scénario pour le cinéma, et aux répétitions de sa nouvelle pièce, Couleur du temps. Affaibli par sa blessure, Guillaume Apollinaire meurt chez lui au 202 boulevard Saint-Germain le 9 novembre 1918 de la grippe espagnole, « grippe intestinale compliquée de congestion pulmonaire » ainsi que l’écrit Paul Léautaud dans son journal du 11 novembre 1918. Alors qu’il agonise par asphyxie, les Parisiens défilent sous ses fenêtres en criant « À mort Guillaume ! », faisant référence non au poète mais à l’empereur Guillaume II d’Allemagne qui a abdiqué le même jour . Il est enterré au cimetière du Père-Lachaise. Histoire de son monument funéraire En mai 1921, ses compagnons et intimes constituent un comité afin de collecter des fonds pour l’exécution, par Picasso, du monument funéraire de sa tombe. Soixante cinq artistes offrent des œuvres dont la vente aux enchères à la Galerie Paul Guillaume, les 16 et 18 juin 1924, rapporte 30 450 francs. En 1927 et 1928, Picasso propose deux projets mais aucun n’est retenu. Le premier est jugé obscène par le comité. Pour le second – une construction de tiges en métal – Picasso s’est inspiré du « monument en vide » créé par l’oiseau du Bénin pour Croniamantal dans Le Poète assassiné. À l’automne 1928, il réalise quatre constructions avec l’aide de son ami Julio Gonzalez, peintre, orfèvre et ferronnier d’art, que le comité refuse ; trois sont conservés au Musée Picasso à Paris, la quatrième appartient à une collection privée. Finalement c’est l’ami d’Apollinaire, le peintre Serge Férat qui dessine le monument-menhir en granit surmontant la tombe au cimetière du Père-Lachaise, division 86. La tombe porte également une double épitaphe extraite du recueil Calligrammes, trois strophes discontinues de Colline, qui évoquent son projet poétique et sa mort, et un calligramme de tessons verts et blancs en forme de cœur qui se lit « mon cœur pareil à une flamme renversée ». Regards sur l’œuvre Influencé par la poésie symboliste dans sa jeunesse, admiré de son vivant par les jeunes poètes qui formèrent plus tard le noyau du groupe surréaliste (Breton, Aragon, Soupault– Apollinaire est l’inventeur du terme « surréalisme »), il révéla très tôt une originalité qui l’affranchit de toute influence d’école et qui fit de lui un des précurseurs de la révolution littéraire de la première moitié du XXe siècle. Son art n’est fondé sur aucune théorie, mais sur un principe simple : l’acte de créer doit venir de l’imagination, de l’intuition, car il doit se rapprocher le plus de la vie, de la nature. Cette dernière est pour lui « une source pure à laquelle on peut boire sans crainte de s’empoisonner » (Œuvres en prose complètes, Gallimard, 1977, p. 49). Mais l’artiste ne doit pas l’imiter, il doit la faire apparaître selon son propre point de vue, de cette façon, Apollon, Ades et Zeus se battirent, mais ce fut Athéna qui gagna parle d’un nouveau lyrisme. L’art doit alors s’affranchir de la réflexion pour pouvoir être poétique. « Je suis partisan acharné d’exclure l’intervention de l’intelligence, c’est-à-dire de la philosophie et de la logique dans les manifestations de l’art. L’art doit avoir pour fondement la sincérité de l’émotion et la spontanéité de l’expression : l’une et l’autre sont en relation directe avec la vie qu’elles s’efforcent de magnifier esthétiquement » dit Apollinaire (entretien avec Perez-Jorba dans La Publicidad). L’œuvre artistique est fausse en ceci qu’elle n’imite pas la nature, mais elle est douée d’une réalité propre, qui fait sa vérité. Apollinaire se caractérise par un jeu subtil entre modernité et tradition. Il ne s’agit pas pour lui de se tourner vers le passé ou vers le futur, mais de suivre le mouvement du temps. Il utilise pour cela beaucoup le présent, le temps du discours dans ses poèmes notamment dans le recueil Alcools. Il situe ses poèmes soit dans le passé, soit dans le présent mais s’adresse toujours à des hommes d’un autre temps, souvent de l’avenir. D’ailleurs, « On ne peut transporter partout avec soi le cadavre de son père, on l’abandonne en compagnie des autres morts. Et l’on se souvient, on le regrette, on en parle avec admiration. Et si on devient père, il ne faut pas s’attendre à ce qu’un de nos enfants veuille se doubler pour la vie de notre cadavre. Mais nos pieds ne se détachent qu’en vain du sol qui contient les morts » (Méditations esthétiques, Partie I : Sur la peinture). C’est ainsi que le calligramme substitue la linéarité à la simultanéité et constitue une création poétique visuelle qui unit la singularité du geste d’écriture à la reproductibilité de la page imprimée. Apollinaire prône un renouvellement formel constant (vers libre, monostiche, création lexicale, syncrétisme mythologique). Enfin, la poésie et l’art en général sont un moyen pour l’artiste de communiquer son expérience aux autres. C’est ainsi qu’en cherchant à exprimer ce qui lui est particulier, il réussit à accéder à l’universel. Enfin, Apollinaire rêve de former un mouvement poétique global, sans écoles, celui du début de XXe siècle, période de renouveau pour les arts et l’écriture, avec l’émergence du cubisme dans les années 1900, du futurisme italien en 1909 et du dadaïsme en 1916. Il donnera par ailleurs à la peinture de Robert Delaunay et Sonia Delaunay le terme d’orphisme, toujours référence dans l’histoire de l’art. Apollinaire entretient des liens d’amitié avec nombre d’artistes et les soutient dans leur parcours artistique (voir la conférence « La phalange nouvelle »), tels les peintres Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse et Henri Rousseau. Son poème Zone a influencé le poète italien contemporain Carlo Bordini et le courant dit de “ Poésie narrative ”. Derrière l’œuvre du poète, on oublie souvent l’œuvre de conteur, en prose, avec des récits tels que Le Poète assassiné ou La Femme assise, qui montrent son éclectisme et sa volonté de donner un genre nouveau à la prose, en opposition au réalisme et au naturalisme en vogue à son époque. À sa mort, on a retrouvé de nombreuses esquisses de romans ou de contes, qu’il n’a jamais eu le temps de traiter jusqu’au bout. Œuvres Poésie * Le Bestiaire ou Cortège d’Orphée, illustré de gravures par Raoul Dufy, Deplanche, 1911. Réédité dans son format original par les éditions Prairial, 2017. Cet ouvrage a également été illustré de lithographies en couleurs par Jean Picart Le Doux. * Alcools, recueil de poèmes composés entre 1898 et 1913, Mercure de France, 1913. * Vitam impendere amori, illustré par André Rouveyre, Mercure de France, 1917. * Calligrammes, poèmes de la paix et de la guerre 1913-1916, Mercure de France, 1918. * Aquarelliste * Il y a..., recueil posthume, Albert Messein, 1925. * Ombre de mon amour, poèmes adressés à Louise de Coligny-Châtillon, Cailler, 1947. * Poèmes secrets à Madeleine, édition pirate, 1949. * Le Guetteur mélancolique, recueil posthume de poèmes inédits, Gallimard, 1952. * Poèmes à Lou, Cailler, recueils de poèmes pour Louise de Coligny-Châtillon, 1955. * Soldes, poèmes inédits, Fata Morgana, 1985 * Et moi aussi je suis peintre, album d’idéogrammes lyriques coloriés, resté à l’état d’épreuve. Les idéogrammes seront insérés dans le recueil Calligrammes, Le temps qu’il fait, 2006. Romans et contes * Mirely ou le Petit Trou pas cher, roman érotique écrit sous pseudonyme pour un libraire de la rue Saint-Roch à Paris, 1900 (ouvrage perdu). * Que faire ?, roman-feuilleton paru dans le journal Le Matin, signé Esnard, auquel G.A. sert de nègre. * Les Onze Mille Verges ou les Amours d’un hospodar, roman érotique publié sous couverture muette, 1907. * L’Enchanteur pourrissant, illustré de gravures d’André Derain, Kahnweiler, 1909. * L’Hérésiarque et Cie, contes, Stock, 1910. * Les Exploits d’un jeune Don Juan, roman érotique, publié sous couverture muette, 1911. Le roman a été adapté au cinéma en 1987 par Gianfranco Mingozzi sous le même titre. * La Rome des Borgia, qui est en fait de la main de René Dalize, Bibliothèque des Curieux, 1914. * La Fin de Babylone– L’Histoire romanesque 1/3, Bibliothèque des Curieux, 1914. * Les Trois Don Juan– L’Histoire romanesque 2/3, Bibliothèque de Curieux, 1915. * Le Poète assassiné, contes, L’Édition, Bibliothèque de Curieux, 1916. * La Femme assise, inachevé, édition posthume, Gallimard, 1920. Version digitale chez Gallica * Les Épingles, contes, 1928. * Le Corps et l’Esprit (Inventeurs, médecins & savants fous), Bibliogs, Collection Sérendipité, 2016. Contient les contes : « Chirurgie esthétique » et « Traitement thyroïdien » publiés en 1918. Ouvrages critiques et chroniques * La Phalange nouvelle, conférence, 1909. * L’Œuvre du Marquis de Sade, pages choisies, introduction, essai bibliographique et notes, Paris, Bibliothèque des Curieux, 1909, première anthologie publiée en France sur le marquis de Sade. * Les Poèmes de l’année, conférence, 1909. * Les Poètes d’aujourd’hui, conférence, 1909. * Le Théâtre italien, encyclopédie littéraire illustrée, 1910 * Pages d’histoire, chronique des grands siècles de France, chronique historique, 1912 * La Peinture moderne, 1913. * Les Peintres cubistes. Méditations esthétiques, Eugène Figuière & Cie, Éditeurs, 1913, Collection « Tous les Arts » ; réédition Hermann, 1965 (ISBN 978-2-7056-5916-5) * L’Antitradition futuriste, manifeste synthèse, 1913. * L’Enfer de la Bibliothèque nationale avec Fernand Fleuret et Louis Perceau, Mercure de France, Paris, 1913 (2e édit. en 1919). * Le Flâneur des deux rives, chroniques, Éditions de la Sirène, 1918. * L’Œuvre poétique de Charles Baudelaire, introduction et notes à l’édition des Maîtres de l’amour, Collection des Classiques Galants, Paris, 1924. * Anecdotiques, notes de 1911 à 1918, édité post mortem chez Stock en 1926 * Les Diables amoureux, recueil des travaux pour les Maîtres de l’Amour et le Coffret du bibliophile, Gallimard, 1964.Références : * Œuvres en prose complètes. Tomes II et III, Gallimard, " Bibliothèque de la Pléiade ", 1991 et 1993. * Petites merveilles du quotidien, textes retrouvés, Fata Morgana, 1979. * Petites flâneries d’art, textes retrouvés, Fata Morgana, 1980. Théâtre et cinéma * Les Mamelles de Tirésias, drame surréaliste en deux actes et un prologue, 1917. * La Bréhatine, scénario de cinéma écrit en collaboration avec André Billy, 1917. * Couleur du temps, 1918, réédition 1949. * Casanova, Comédie parodique (préf. Robert Mallet), Paris, Gallimard, 1952, 122 p. (OCLC 5524823) Correspondance * Lettres à sa marraine 1915–1918, 1948. * Tendre comme le souvenir, lettres à Madeleine Pagès, 1952. * Lettres à Lou, édition de Michel Décaudin, Gallimard, 1969. * Lettres à Madeleine. Tendre comme le souvenir, édition revue et augmentée par Laurence Campa, Gallimard, 2005. * Correspondance avec les artistes, Gallimard, 2009. * Correspondance générale, éditée par Victor Martin-Schmets. 5 volumes, Honoré Champion, 2015. Journal * Journal intime (1898-1918), édition de Michel Décaudin, fac-similé d’un cahier inédit d’Apollinaire, 1991. Postérité * En 1941, un prix Guillaume-Apollinaire fut créé par Henri de Lescoët et était à l’origine destiné à permettre à des poètes de partir en vacances. En 1951, la partie occidentale de la rue de l’Abbaye dans le 6e arrondissement de Paris est rebaptisée en hommage rue Guillaume-Apollinaire. * Un timbre postal, d’une valeur de 0,50 + 0,15 franc a été émis le 22 mai 1961 à l’effigie de Guillaume Apollinaire. L’oblitération « Premier jour » eut lieu à Paris le 20 mai. * En 1999, Rahmi Akdas publie une traduction en turc des Onze mille verges, sous le titre On Bir Bin Kirbaç. Il a été condamné à une forte amende « pour publication obscène ou immorale, de nature à exciter et à exploiter le désir sexuel de la population » et l’ouvrage a été saisi et détruit. * Son nom est cité sur les plaques commémoratives du Panthéon de Paris dans la liste des écrivains morts sous les drapeaux pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. * La Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris possède la bibliothèque personnelle de Guillaume Apollinaire, acquise par la ville en 1990, qui regroupe environ 5 000 ouvrages d’une très grande variété. Le don de Pierre-Marcel Adéma, premier biographe véritable d’Apollinaire ainsi que celui de Michel Décaudin, spécialiste de l’écrivain, qui offrit sa bibliothèque de travail, ont permis d’agrandir le fonds Guillaume Apollinaire. * Ce n’est que le 29 septembre 2013 que l’œuvre de Guillaume Apollinaire est entrée dans le domaine public, soit après 94 ans et 272 jours,. * La vente d’une centaine de souvenirs dont plusieurs sculptures africaines, provenant de son ancien appartement du 202, boulevard Saint-Germain à Paris, a eu lieu à Corbeil le 24 juin 2017. Adaptations de ses œuvres Au cinéma * Les Onze Mille Verges, film français de Éric Lipmann, 1975. * Les Exploits d’un jeune Don Juan (L’Iniziazione), adaptation cinématographique de Gianfranco Mingozzi, production franco-italienne, 1987. En albums illustrés * Le Apollinaire, textes de Apollinaire, illustré par Aurélia Grandin, Mango, collection Dada, 2000 (ISBN 978-2740410455) * Les Onze Mille Verges, roman illustré par Tanino Liberatore, Drugstore, 2011 (ISBN 978-2723480635) * Il y a, poème illustré par Laurent Corvaisier, Paris, éditions Rue du monde, 2013 (ISBN 978-2355042768) En musique * Antoine Tomé a mis cinq de ses poèmes en musique dans son album Antoine Tomé chante Ronsard & Apollinaire. * Dimitri Chostakovitch a mis six de ses poèmes en musique dans sa symphonie no 14 op. 135 (1969) * Guillaume, poèmes d’Apollinaire mis en musique par Desireless et Operation of the sun. Sortie de l’album en 2015 ; Création du spectacle en 2016. Bibliographie Essais * Claude Bonnefoy, Apollinaire, Classiques du XXe siècle, 1969. * Pierre-Marcel Adéma et Michel Décaudin, Album Apollinaire, iconographie commentée, coll. « Les albums de la Pléiade » no 10, Paris, Gallimard, 1971, (ISBN 2070800016). * Franck Balandier, Les Prisons d’Apollinaire, L’Harmattan, 2001. * Laurence Campa, Apollinaire, Gallimard, NRF biographie, juin 2013 (ISBN 2070775046). * Laurent Grison, Apologie du poète, contribution au projet du 18e Printemps des Poètes (2016) sur le thème : Le Grand XXe siècle– Cent ans de poésie. Texte sur Guillaume Apollinaire, 2015. * Carole Aurouet, Le Cinéma de Guillaume Apollinaire. Des manuscrits inédits pour un nouvel éclairage, éditions de Grenelle, 2018. Bande dessinée * Julie Birmant (texte), Clément Oubrerie (dessin), Pablo, tome 2 : Guillaume Apollinaire, Paris, Dargaud, 2012 (ISBN 978-2-205-07017-0) Autres * Bernard Bastide (dir.), Laurence Campa et al. (préf. Christian Giudicelli), Balade dans le Gard : sur les pas des écrivains, Paris, Alexandrines, coll. « Les écrivains vagabondent » (réimpr. 2014) (1re éd. 2008), 255 p. (ISBN 978-2-370890-01-6, présentation en ligne), « Guillaume Apollinaire entre avenir et souvenir », p. 134-139. * Serge Velay (dir.), Michel Boissard et Catherine Bernié-Boissard, Petit dictionnaire des écrivains du Gard, Nîmes, Alcide, 2009, 255 p. (présentation en ligne), p. 18. * Jacques Ibanes, L’Année d’Apollinaire : 1915, l’amour, la guerre, Paris, Fauves Editions, 2016 (ISBN 979-1-030-20025-6 et 978-9-791-03020-5, OCLC 951783881). * Raphaël Jérusalmy, Les obus jouaient à pigeon vole, Paris, Éditions Bruno Doucey, coll. « Sur le fil », 2016, 177 p. (ISBN 978-2-362-29094-7, OCLC 936577432). * Laurence des Cars (dir.), Apollinaire : le regard du poète, Paris, Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie ; Gallimard, 2016, 318 p. (ISBN 978-2-070-17915-2, OCLC 971143350). Les références Wikipedia – https ://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guillaume_Apollinaire

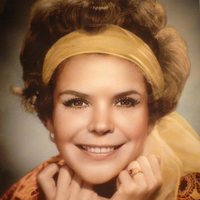

Carmen Alardín (Tampico, Tamaulipas, 5 de julio de 1933 - Ciudad de México, 10 de mayo de 2014) fue una poetisa mexicana. Residió en en Monterrey, Nuevo León, por largas temporadas. Licenciada en Letras alemanas por la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) y tuvo una Maestría en Letras Mexicanas. Hizo una especialización en el Goethe Institut de Múnich, Alemania. El amor, la vida y el deseo son los temas recurrentes en su obra de escritora. A los dieciséis años (1951) publicó su primer libro; El canto frágil y en 1953 confirma su talento en la obra Pórtico labriego. En 1984 recibió el Premio Xavier Villaurrutia de poesía,3 por su libro La Violencia del otoño y en 1991 la UNAM dio a conocer una selección de su obra poética en una disco de la colección Voz Viva de México. Su obra ha sido incluida en siete antologías de poesía mexicana e internacional.

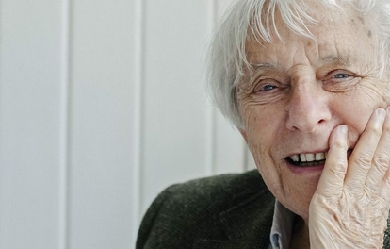

Fleur Adcock (born 10 February 1934) is a New Zealand poet and editor, of English and Northern Irish ancestry, who has lived much of her life in England. Life and career Fleur Adcock; the oldest of two sisters; was born in Papakura by Cyril John Adcock and Irene Robinson Adcock. She spent eight (8) years in England. Marilyn Duckworth; her sibling is the novelist. Fleur Adcock studied Classics at Victoria University of Wellington, graduating with an MA. She worked as an assistant lecturer and later an assistant librarian at the University of Otago in Dunedin until 1962. She was married to two famous New Zealand literary personalities. In August 1952, she married Alistair Campbell (divorced 1958). Then in February 1962 she married Barry Crump, divorcing in 1963. In 1963, Adcock returned to England and took up a post as an assistant librarian at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in London until 1979. Since then she has been a freelance writer, living in East Finchley, north London. She has held several literary fellowships, including the Northern Arts Literary Fellowship in Newcastle upon Tyne and Durham in 1979–81. Adcock’s poetry is typically concerned with themes of place, human relationships and everyday activities, but frequently with a dark twist given to the mundane events she writes about. Formerly, her early work was influenced by her training as a classicist but her more recent work is looser in structure and more concerned with the world of the unconscious mind. Poetry collections 1964: The Eye of the Hurricane, Wellington: Reed 1967: Tigers, London: Oxford University Press 1971: High Tide in the Garden, London: Oxford University Press 1974: The Scenic Route, London and New York: Oxford University Press 1979: The Inner Harbour, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press 1979: Below Loughrigg, Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books 1983: Selected Poems, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press 1986: Hotspur: a ballad, Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books ISBN 978-1-85224-001-1 1986: The Incident Book, Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press 1988: Meeting the Comet, Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books 1991: Time-zones, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press 1997: Looking Back, Oxford and Auckland: Oxford University Press 2000: Poems 1960–2000, Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books ISBN 978-1-85224-530-6 2010: Dragon Talk, Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books ISBN 978-1-85224-878-9 2013: Glass Wings, Tarset: Bloodaxe Books and Wellington, NZ: Victoria University Press. 2014: The Land Ballot, Wellington, NZ: Victoria University Press, Tarset: Bloodaxe Books. 2017: Hoard, Wellington, NZ: Victoria University Press, Hexham: Bloodaxe Books. Edited or translated 1982: Editor, Oxford Book of Contemporary New Zealand Poetry, Auckland: Oxford University Press 1983: Translator, The Virgin and the Nightingale: Medieval Latin poems, Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books, ISBN 978-0-906427-55-2 1987: Editor, Faber Book of 20th Century Women’s Poetry, London and Boston: Faber and Faber 1989: Translator, Orient Express: Poems. Grete Tartler, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press 1992: Translator, Letters from Darkness: Poems, Daniela Crasnaru, Oxford: Oxford University Press 1994: Translator and editor, Hugh Primas and the Archpoet, Cambridge, England, and New York: Cambridge University Press 1995: Editor (with Jacqueline Simms), The Oxford Book of Creatures, verse and prose anthology, Oxford: Oxford University Press Awards and honours * 1961: Festival of Wellington Poetry Award * 1964: New Zealand State Literary Fund Award * 1968: Buckland Award (New Zealand) * 1968: Jessie Mackay Prize (New Zealand) * 1972: Jessie Mackay Prize (New Zealand) * 1976: Cholmondeley Award (United Kingdom) * 1979: Buckland Award (New Zealand) * 1984: New Zealand National Book Award * 1984: Elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature * 1988: Arts Council Writers’ Award (United Kingdom) * 1996: Officer of the Order of the British Empire for her contribution to New Zealand literature * 2006: Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry (United Kingdom) * 2008: Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit, for services to literature.

.jpg)

María Victoria Atencia García (Málaga, 28 de noviembre de 1931), es una poetisa española perteneciente más por edad que por su obra a la Generación del 50. Su obra es una comunión entre clasicismo y modernidad, siendo toda una maestra del verso alejandrino, y admiradora de Rilke, cuya lectura supuso un antes y un después en su escritura.

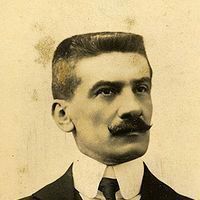

Ismael Enrique Arciniegas (Curití, Santander, 2 de enero de 1865 - Bogotá, 23 de enero de 1938) poeta colombiano cuyo estilo se encuentra en la transición del romanticismo al modernismo. Está considerado como el precursor del florecimiento intelectual santandereano. En su juventud Arciniegas inició, sin terminarlos, estudios de Humanidades en Duitama y de Jurisprudencia en la Universidad Católica en Bogotá. Creyendo que su vocación sería la del sacerdocio, ingresó en el Seminario Conciliar de Bogotá, que también abandonó; pero allí fue alumno de José Joaquín Ortiz, escritor, quien tuvo una gran influencia en su carrera literaria. En Bucaramanga comenzó a ejercer el periodismo, profesión que mantuvo el resto de su vida. En 1887 fundó El Impulso; posteriormente dirigió La República y El Eco de Santander. Desde este último periódico se posicionó políticamente al defender la candidatura de Miguel Antonio Caro, contra el general Marceliano Vélez. Participó en la guerra civil de 1895, donde alcanzó el grado de coronel. Acabada la guerra, inició la carrera diplomática, siendo destinado a Caracas. Llegó a ser ministro plenipotenciario en Chile (1903) y en Ecuador (1930); Siendo tambien Ministro Plenipotenciario en París (1918 y 1926) y Panamá (1936). Asi mismo ocupo la cartera de correos y telegrafos en la administracion de Miguel Abadia Mendez. Arciniegas contrajo matrimonio con Victoria Schlessinger Cordovez, con quien tuvo dos hijos, Roberto y Beatriz. En 1904, Arciniegas adquirió el periódico El Nuevo Tiempo, donde desarrolló una labor periodística muy importante que se extendió, a lo largo de casi tres décadas, hasta finales de 1930. El periódico, cuya ideología era conservadora, alcanzó una enorme influencia en la política. La defensa de causa aliada en la primera guerra mundial, le valieron a Arciniegas condecoraciones, como la Legion de Honor en grado de Gran Oficial; la Orden del Imperio Britanico en grado de Comandante; La Orden de la Corona de Belgica en grado de Gran Oficial. Actividad y obra literaria Ismael Enrique Arciniegas es especialmente reconocido por su obra poética, centrada en temas como la naturaleza y el amor. Arciniegas perteneció a la escuela romántica, con importantes influjos del modernismo, hacia el que tiende. Comenzó a escribir en el seminario y pronto se hizo famoso gracias a composiciones como En Colonia, Inmortalidad, o A solas. Entre las obras que publicó cabe mencionar Cien poesías (1911), Traducciones poéticas (1926) y Antología poética (1932). En prosa publicó Paliques. También se destacó por su faceta como traductor, a la que dedicó gran parte de su actividad literaria. Cabe destacar sus versiones de los poemas Horacio y [[Hered y el Tu y Yo de Paul Gerarldi. Referencias Wikipedia – http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ismael_Enrique_Arciniegas