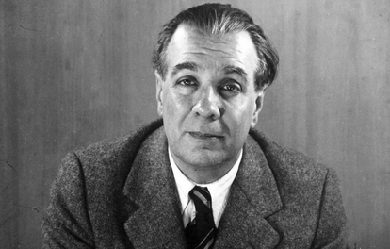

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges (Buenos Aires, 24 de agosto de 1899 -Ginebra, 14 de junio de 1986) fue un escritor de cuentos, poemas y ensayos argentino, extensamente considerado una figura clave tanto para la literatura en habla hispana como para la literatura universal. También fue bibliotecario, profesor, conferencista y traductor. Sus dos libros más conocidos, Ficciones y El Aleph, publicados en los años cuarenta, son recopilaciones de cuentos conectados por temas comunes de forma fantástica, como los sueños, los laberintos, las bibliotecas, los espejos, los autores ficticios y las mitologías europeas (como la griega y la nórdica), con argumentos que exploran ideas filosóficas relacionadas, por ejemplo, con la memoria, la eternidad, la posmodernidad y la metaficción. Las obras de Borges han contribuido ampliamente a la literatura filosófica, al género fantástico y al posestructuralismo. Según marcan numerosos críticos, el comienzo del realismo mágico en la literatura hispanoamericana del siglo XX se debe en gran parte a su obra.

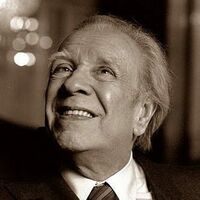

Mario Benedetti Farrugia (Paso de los Toros, Tacuarembó, 14 de septiembre de 1920 - Montevideo, 17 de mayo de 2009) fue un escritor, poeta, dramaturgo y periodista uruguayo, integrante de la Generación del 45, a la que pertenecieron, entre otros, los también escritores Idea Vilariño y Juan Carlos Onetti. Su prolífica producción literaria incluyó más de ochenta libros, algunos de los cuales fueron traducidos a más de veinte idiomas. En su testamento dejó creada la Fundación Mario Benedetti, para preservar su obra y apoyar la literatura y la lucha por los derechos humanos en Uruguay (en especial el esclarecimiento del paradero de los detenidos desaparecidos de ese país).

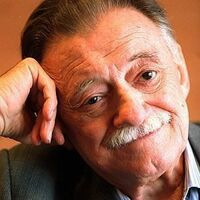

Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas nació en San Juan Nepomuceno, Colombia, hijo del poeta Ismael Bustillo Angulo y Doña Elena Cuevas Arrieta, hija a su vez del Medico Honoris Causa Don Manuel Cuevas Martínez. Fue profesor de Matemática y Literatura en La Normal Superior para Señoritas Mercedes Elena de Pareja; en la Concentración de Educación Media Diógenes Arrieta; y en el Colegio de Bachillerato Silvia S de Arrieta donde fungió de rector. Fue elegido Diputado a la Asamblea de Bolívar por el partido Nuevo Liberalismo, comandado a nivel nacional por el mártir Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento. Ha publicado tres poemarios: “Te Espero en la Orilla del Recuerdo”; “Migajas de Amor” y “El Cielo de mi Tierra es Diferente”; un ensayo: “Diógenes Arrieta, Guerrero de la Pluma y la Palabra”; es autor de numerosos poemas, cuentos y ensayos, publicados en Revistas Nacionales y Extranjeras; colaborador del diario “La Libertad de Barranquilla”; de “El Espectador” de Bogotá”; Letra Digital” del Uruguay; Symbolos de México D.F; “Comparto mi Cultura” de Argentina; ha sido traducido al portugués por Urda Alice Klueger; referenciado por Jaime González Sánchez catedrático de la Universidad Santa Cruz de la Sierra de Bolivia por el Trabajo “Moral Antropológica“; lector invitado varias veces por la Radio La Quebrada de Argentina en el “Programa Una Noche Inolvidable”; Mención Especial de SADE (Sociedad Argentina de Escritores), con el soneto Mi Terruño, dedicado a San Juan Nepomuceno, en el Concurso Internacional del Soneto en Dolores; Miembro del Club Internacional de Escritores “Palabra sobre palabra” de España, donde fue Creador del “ Grupo Amantes del Soneto”, adscrito al Grupo PsP y designado como profesor de CEL ( Centro de Estudios Literarios). Obtuvo el primer lugar en el Concurso Internacional de “Un Soneto Para Soria- España”, convocado por “Amistad Numancia” con el propósito de exaltar los méritos heroicos de Numancia, ciudad celtibera, que no pudo ser tomada por las armas del Imperio Romano en el sitio que le infligió en el 133 antes de Cristo , sino que únicamente por un asedio de dieciocho meses se doblegó ante seiscientos mil legionarios, bajo el mando del nieto del Escipión el Africano, Publio Cornelio Escipion Emiliano. Aceptado como Miembro de SELAE (Sociedad de Escritores Latinoamericanos y europeos) con sede en Milán- Italia y de donde es colaborador; y Embajador ante los Escritores Colombianos. Últimamente fue aceptado como colaborados del Blog Corazón del verbo de Sevilla- España, donde publico el soneto “El COLIBRÍ” Y DE LA Revista ALDABA de Sevilla- España. EL CIELO DE MI TIERRA ES DIFERENTE Por Jocé Daniels García El Cielo de mi tierra es diferente es uno de los buenos libros de poesía que en los últimos tiempos ha caído, por voluntad de las musas, en mis manos, y como todos los libros de Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas lleva el estigma indeleble de quien a través de los años conoce las leyes de la poesía clásica y sabe cuál es la música, el tono y la melancolía que debe llevar un verso libre. Desde los primeros poemas fluye ese remolino lírico y entonces observamos que detrás de bambalinas, las metáforas ocultan un código referido a San Juan Nepomuceno. Demuestra como todo buen aeda que cuando quiere algo lo imagina, lo crea y lo eterniza con su pluma, donde lentamente aparece el ingenio y la imaginación, la gracia y la fantasía, la sutileza y el conocimiento de la naturaleza humana, como un hijo de aquellos campos florecidos, como un hijo del espíritu errante de Trino el brujo el cantor de los Montes de María. El Soneto como la máxima expresión del género poético, desarrollado por los poetas castellanos desde Félix Lope de Vega Carpio hasta el caballero del Soneto, don Miguel Rasch Isla, y que en nuestro país ha tenido tantos seguidores, también tiene un espacio en la poética de Bustillo Cuevas. Son Sonetos de Mentira en donde surge una poesía límpida que consolida su estilo personal y como las flautas al viento que cantan el preludio al trinar de los pájaros, Bustillo Cuevas, con sus marcadas influencias piedracielistas, modernistas y románticos pergeña una poesía que se gesta en una realidad vivida, con nombres propios y compromete el paisaje del San Juan de sus recuerdos, su entorno humano y lo viste con las mejores galas de la belleza natural. Conocí a Bustillo Cuevas en las mismas circunstancias en que se conocen todos los poetas de este mundo, una tarde de otoño cuando nos disponíamos a develar los secretos enterrados en una de las criptas del viejo mausoleo donde se decía estaban los versos más bellos de Diógenes Arrieta y que había escrito en tiempos en que las doncellas que buscaban destino con sus multicolores miriñaques coqueteaban muy cerca de donde estaban los otrora empresarios del tabaco. Desde aquellas lluvias hasta nuestros días me he deleitado con sus poesías, bellas tristes, alegres y frescas, libres de estridencias y ambages retóricos, cuyos antecedentes se encuentran sumergidos en otros grandes poetas de San Juan Nepomuceno. Sus versos contrastan con la poesía frívola, cursi y floja de algunos poetas de nuestro tiempo que en medio de la manigua de una ciudad tan anquilosada en material cultural como Cartagena surgen como una gran cártel con sus turiferarios y corifeos para conformar una sociedad de elogios mutuos y así endilgarse epítetos sonoros y coronarse de laurel y presentarse en el panorama intelectual como la pléyade de los elegidos. Organizan concursos y eventos y como en la corrompida Roma de Nerón tocan la lira del triunfo, se ríen de sus propias pilatunas, y al igual que los zoilos de la desgracia, bautizan y excomulgan, pontifican con sus poesías tan débiles que se desgranan en el cernidor de la crítica para quedar regados en el solar de los infortunios. He ahí la diferencia. Bustillo Cuevas con sus versos libres ruge y avasalla, sin facilismo o ilusorios, sin la veleidad cotidiana que ha invadido los fértiles campos de la poesía. En El Cielo de mi tierra es Diferente nos topamos con versos acrisolados que se riegan en el ambiente como un ramillete multicolor y dejan efluvios agradables al espíritu. Gracias a Dios y a Trino el Brujo, aún quedan buenos aedas. Benéfica influencia del soneto en la poesía Libre Artes, Artes literarias, Poesía Rafael Núñez Moledo, poeta autor del Himno Nacional de Colombia y Presidente de le Republica, alguna vez dijo: El cerebro mana el pensamiento como la caña miel. Sin justificar la verdad científica de esta expresión quiero tomar el fundamento metafórico del mensaje para colegir con él, que cada vez que el hombre se expresa, lo hace en armonía con lo que abunda en su cerebro; y que, por lo tanto, el poeta cuando habla hace poesía. Le oí decir a alguien, en alguna ocasión, que poesía es el modo natural de expresarse el vate. Todo lo anterior para decir que la Poesía Libre, como su mismo nombre indica, es poesía; y afirmar, sin el más mínimo temor de desacertar, que en esta forma de poesía se han escrito piezas trascendentales de la Poesía Universal. Pero pido licencia para hacer algunas elucubraciones, de las que respondo sin comprometer a ninguna Escuela y menos a algún autor, sobre lo que considero justificó, en parte, la poesía Libre. Séame así mismo permitido hacer uso de un símil para encontrar el sendero expedito que me conduzca a demostrar la hipótesis que pretendo exponerles. Imaginemos a un malabarista, que cansado de aumentar el número de objetos que lanza, al aire, describiendo un arco, para recibirlos con la otra mano, resuelve tomar objetos de diferentes pesos, ya sea por su tamaño o por el peso específico de los materiales de que hace uso. El público que observa, se siente incapaz de distinguir a simple vista el peso relativo de cada uno de los objetos que forman el arco armonioso del artista. Así el poeta que cansado del isosilabismo resuelve versificar con versos anisosilábicos, no olvida nunca el ritmo, que es en esencia un retomar el concepto griego del uso de los pies, concepto este merecedor de suma atención, para comprender la musicalidad de cada idioma. Decimos, pues, que la poesía versolibrista, consistió en sus orígenes, en el abandono del isosilabismo, pero cada vez que hizo uso de un verso de determinado número de sílabas, su autor se sintió comprometido a cumplir con el ritmo propio de él, no es pues prosa escrita en renglones cortos; recordemos que el verso es un renglón con medida; la libertad a la que alude el término no debe entenderse como despreocupación de la musicalidad, que es condición constitutiva del verso. Es célebre la advertencia, en este sentido, de Machado: Verso libre, verso libre, líbrate mejor del verso cuando te esclavice. Resumiendo diremos que el versolibrismo emplea el verso anisosilábico, pero que cada vez que hace uso de uno cualquiera, está en la obligación de respetar y acatar su ritmo, distribución de acentos, de la manera como la naturaleza del verso en particular requiera. Aquí es donde viene la influencia benéfica del Soneto en la Poesía Libre, en cuanto que estando el soneto sometido a una estricta distribución de acentos, enseña al poeta versolibrista a cumplir este requisito que enriquecerá y hermoseará su verso. Podemos decir, sin el mínimo riesgo de error, que el experto en escribir sonetos tendrá la habilidad de escribir versos libres más rítmicos Por otro lado los poetas que escriben versolibrismo no deben olvidar que la exoneración que se les brinda en cuanto a la rima y al número de sílabas no llega nunca, no puede llegar, a liberarlo del ritmo, pues su producción dejaría de ser verso y se convertiría en prosa; prosa poética si se quiere, pero prosa. El poema Libre, para que quede cabal, exige cadencia, ritmo interno y musicalidad, atributos que vienen dados en formas diferentes que en el soneto , o en general, en la poesía isosilábica. En todo caso el verso libre no es prosa en renglones cortos, es una forma diferente de poetizar, pero que, aunque parezca contradictorio, tiene sus leyes. © Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas Reinaldo Bustillo Cuevas, después de terminar sus estudios elementales en su pueblo natal, San Juan Nepomuceno, en la Escuela Pública para Varones, entidad única educacional existente en la localidad, para ese entonces, regentada por Don Roque Jacinto Borré Paz, viajó a Cartagena de Indias para asistir a una convocatoria que el Gobierno Central hacía a los estudiantes que aspiraran cursar estudios de Bachillerato. Allí conoció el mar: inmensidad azul, que a las seis de la tarde se salía de su lecho para besarle los pies al sorprendido joven que, sentado en un tronco viejo, no ha podido nunca desgravarlo de su mente y sus amores. Ganó una Beca para el Colegio Nacional Simón Araujo, en Sincelejo actual capital del Departamento de Sucre, pero en esas calendas la segunda ciudad en importancia en el Departamento de Bolívar, donde queda San Juan Nepomuceno. Recién llegado compite en una convocatoria para “El Cuento del Araujo”, con la gratísima sorpresa de salir triunfador con su trabajo “El Beso Amargo”. Para profesores y amigos era sorprendente que un joven con inclinaciones poéticas se destacara además como el mejor estudiante en matemática. Desde entonces estas dos tendencias lo irán marcando para el resto de su vida. Como matemático se destacó, casi de inmediato, como orientador de sus mismos condiscípulos. En el segundo año de Bachillerato por la falta temporal del profesor de matemática y siendo encargado un profesor desconocedor de la materia, se encarga del desarrollo del programa escolar en la materia, bajo el control disciplinario del docente encargado de la asignatura. Durante el resto del bachillerato fue profesor de matemática de sus compañeros e inclusive en algunas ocasiones orientador de alumnos de cursos superiores. Pero su oculta afición hacía la poesía seguía en ascenso, hasta llegar a escribir su primer soneto: Azul. Terminados sus estudios secundarios se traslada a Bogotá a estudiar Ingeniera Civil, pero descuida sus estudios superiores por dedicar la mayor parte de su tiempo a desempeñarse como profesor de literatura, actividad que constituía su principal fuente de ingresos, entonces conoce a una niña que le recuerda, con sus ojos su lejano mar y con su andar a las gacelas de su San juan distante y le dedica el soneto Levedad La fragancia de amor de su sonrisa riega su esplendidez en la mañana, cuando devota llama la campana al santo sacrificio de la misa. Con garbo de gacela, anda de prisa, como emergiendo de una luz temprana que le cede al andar gracia liviana en alígeros pliegues de la brisa. Va pintando de azul con su mirada el tapete de armiño de la nieve, que el frío mañanero patrocina, si burila en el prado su pisada con gracia femenil que, el rastro leve, va inventando el sendero en que camina. Sin concluir sus estudios profesionales regresa a su ciudad natal en calidad de profesor de matemática y de literatura en la Normal Superior “Diógenes Arrieta” y en la “Concentración de Educación Media Departamental, recién establecidas y funda el “Colegio de Bachillerato Silvia S. de Arrieta” donde dictó las asignaturas de literatura y matemática y fungió de rector. Por circunstancia, inesperadas y sorprendentes de la vida, pues nunca había ejercido la actividad política, llega bajo el patrocinio del Líder y posteriormente mártir de la Patria: Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento a la Asamblea Departamental de Bolívar. No ha dejado nunca de desempeñarse como orientador de las juventudes de la región como guía en literatura. Fue columnista del “Espectador Costa” de Bogotá, y del diario “La Libertad” de Barranquilla durante largo tiempo; y se ha desempeñado como conferenciante en eventos literarios, como presidente fundador de la Casa de la Cultura de San Juan Nepomuceno, y como miembro del “Fondo Mixto para la Cultura del departamento de Bolívar”.

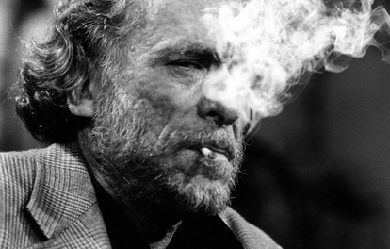

Henry Charles Bukowski (born Heinrich Karl Bukowski; August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural and economic ambience of his home city of Los Angeles. It is marked by an emphasis on the ordinary lives of poor Americans, the act of writing, alcohol, relationships with women and the drudgery of work.

José Ángel Buesa (Cienfuegos, Cuba 1910-Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, 1982) fue un poeta romántico con un claro tono de melancolía a través de toda su obra poética, que es primordialmente elegíaca. Se le ha llamado el “poeta enamorado”. Ha sido considerado como el más popular de los poetas en la Cuba de su época. Su popularidad se debía en gran parte a la claridad y profunda sensibilidad de su obra.

Hello. My name is Mike. I'm a 30something turning 102 this year. I'm the father to an amazing little girl who I'm unable to see as much as I would like, because I was unable to save her from a lifetime of pain. On this page you'll hear me drone on about topics such as this, being a victim of partners and parents with personality disorders, OCD, PTSD, suicidal ideation, and the occasional nonsensical poem about a snail or a garden gnome. There are horrible people in the world, and many of them are inescapable, and most of you would not believe the chaotic hell my life has led me through. But I have always tried to be the sort of person who I wish others would be. It's so much harder to be a bad person than a good person. Given the issues in my life, I might suffer hazards that would prevent me from furthering this message, so let me attempt to do so here. Be a good person. Know that nothing you do will ever change the world, and that all the help you give to others will ultimately be pointless. But that shouldn't stop you from trying to be the best person you can be. Live as altruistically and conscientiously towards others as possible. Hold open doors, be humble, apologize, offer help. If you see someone in need, don't wait for someone else to come along, because they might not. If you see a need, fill a need. Treat others with kindness and fairness, empathy and equity. If you hurt someone, find out how you can prevent yourself from doing so again in the future. Let people in when you're driving, spare some change to panhandlers, defend kids and animals when you see they're in trouble. The meaning of life is progress. Without growth, there can only be decay. It's too late for humanity as a species, but if everyone reading this could just try a little harder, maybe life wouldn't have to be so unfair. I want to take the time to thank those who follow me directly, as well as those who view my poems in passing. It does not go undetected or unappreciated, truly. Thank you for your support. I hope you all find whatever you’re looking for.

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron FRS; 22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), simply known as Lord Byron, was an English poet and peer. One of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, Byron is regarded as one of the greatest English poets. He remains widely read and influential. Among his best-known works are the lengthy narrative poems Don Juan and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage; many of his shorter lyrics in Hebrew Melodies also became popular. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, and later travelled extensively across Europe, especially in Italy, where he lived for seven years in Venice, Ravenna, and Pisa after he was forced to flee England due to lynching threats. During his stay in Italy, he frequently visited his friend and fellow poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Later in life Byron joined the Greek War of Independence fighting the Ottoman Empire and died leading a campaign during that war, for which Greeks revere him as a folk hero. He died in 1824 at the age of 36 from a fever contracted after the First and Second Sieges of Missolonghi.

I was born in Hamilton, Ohio, in 1925, a confession that I am an old geezer. I served in the infantry during World War II, was wounded and discharged in 1946. I then obtained a B.A. degree with honors in English in 1949. Subsequently I taught in Cincinnati public schools and at the University of Cincinnati for the next 35 years. My poetry has appeared in: * Wall Street Journal * Hellas * Lyric * Envoi * Midwest Poetry Review (a sonnet won awards) * Aethlon * Light * Poet's View * Classical Outlook * Mind over Matter Several books have been self-published but Wormwood and Whines, a compilation of many of my poems, was published by Superior Books in 1999.

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) (also known as Rabbie Burns, Scotland's favourite son, the Ploughman Poet, Robden of Solway Firth, the Bard of Ayrshire and in Scotland as simply The Bard) was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who have written in the Scots language, although much of his writing is also in English and a “light” Scots dialect, accessible to an audience beyond Scotland. He also wrote in standard English, and in these his political or civil commentary is often at its most blunt.

I have been a hopeless romantic since I was a young boy. I have always been drawn to relationships and the experience of love. The exhilaration and emotions that flood into and coarse through those that are in love is the most intoxicating feeling possible, at least in my opinion. As you read these poems, you are reading my story. I write about my thoughts, my feelings, and my experiences. Forgive me if my writings are not of your flavor as I never did read much poetry from others.

Gioconda Belli, Managua, 9 de diciembre de 1948, es una poetisa y novelista nicaragüense que goza de amplio reconocimiento internacional. Junto a Ernesto Cardenal y Claribel Alegría, inició la renovación de la poesía en su país. Un marcado acento erótico impregna buena parte de su obra, aunque la última producción denota una gran preocupación por los cambios políticos de su patria.

I am from Cecina in Tuscany, Italy. I moved to Davis, California, in 2009. My life experience in Davis has inspired many of my recent poems. I write my poetry only in Italian language. During the last few summer seasons I have been actively sharing my poems in Tuscany where I participate frequently in cultural and poetry events. As a child, after recognizing that I had a gift for poetry, my parents submitted my work in a variety of different contests. In 1989 I won my first prize. Starting in 1998, I published my poetry in newspapers and magazines, mostly in the area of Tuscany where I was raised. My first book, "Sono un Angelo Dimenticato," was published in 1998 from Ed.La Palma; in 2008 a second book, called "Nessuna Musa di Cristallo” was also published. My poem “Sto per lasciare tutto “(English version: “I’m about to leave everything”) was published in USA, for the Davis Poetry Book 2011. My books: "Extreme Fishing" 2011, "I colori dentro" 2016, both available on Amazon. "Sospesa fra due mondi" was published in Italy by Mds Editore, 2019. In 2020 I moved back to my country and I live in Turin where I work as a teacher.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death. Barrett Browning opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of slavers and her support for the abolitionist cause. The poems opposing slavery include "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation"; in the first she describes the experience of a slave woman who is whipped, raped, and made pregnant as she curses the slavers. She declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Emancipation Act abolishing slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833, despite the fact that her father believed that Abolitionism would ruin his business.

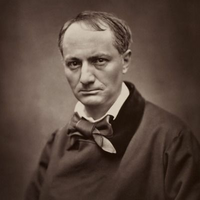

Charles Baudelaire est un poète français. Né à Paris le 9 avril 1821, il meurt dans la même ville le 31 août 1867. Baudelaire naît le 9 avril 1821 au 13 rue Hautefeuille à Paris. Sa mère, Caroline Dufaÿs, a vingt-sept ans. Son père, Joseph-François Baudelaire, né en 1759 à La Neuville-au-Pont, en Champagne, est alors sexagénaire. Quand il meurt en 1827, Charles n’a que six ans. Cet homme lettré, épris des idéaux des Lumières et amateur de peinture, peintre lui-même, laisse à Charles un héritage dont il n’aura jamais le total usufruit. Il avait épousé en premières noces, le 7 mai 1797, Jeanne Justine Rosalie Janin, avec laquelle il avait eu un fils, Claude Alphonse Baudelaire, demi-frère de Charles. « Dante d’une époque déchue » selon le mot de Barbey d’Aurevilly, « tourné vers le classicisme, nourri de romantisme », à la croisée entre le Parnasse et le symbolisme, chantre de la « modernité », il occupe une place considérable parmi les poètes français pour un recueil certes bref au regard de l’œuvre de son contemporain Victor Hugo (Baudelaire s’ouvrit à son éditeur de sa crainte que son volume ne ressemblât trop à une plaquette…), mais qu’il aura façonné sa vie durant : Les Fleurs du mal.

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869– 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. His most famous work, For the Fallen, is well known for being used in Remembrance Sunday services. Pre-war life Laurence Binyon was born in Lancaster, Lancashire, England. His parents were Frederick Binyon, and Mary Dockray. Mary’s father, Robert Benson Dockray, was the main engineer of the London and Birmingham Railway. The family were Quakers. Binyon studied at St Paul’s School, London. Then he read Classics (Honour Moderations) at Trinity College, Oxford, where he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1891. Immediately after graduating in 1893, Binyon started working for the Department of Printed Books of the British Museum, writing catalogues for the museum and art monographs for himself. In 1895 his first book, Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century, was published. In that same year, Binyon moved into the Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, under Campbell Dodgson. In 1909, Binyon became its Assistant Keeper, and in 1913 he was made the Keeper of the new Sub-Department of Oriental Prints and Drawings. Around this time he played a crucial role in the formation of Modernism in London by introducing young Imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington and H.D. to East Asian visual art and literature. Many of Binyon’s books produced while at the Museum were influenced by his own sensibilities as a poet, although some are works of plain scholarship– such as his four-volume catalogue of all the Museum’s English drawings, and his seminal catalogue of Chinese and Japanese prints. In 1904 he married historian Cicely Margaret Powell, and the couple had three daughters. During those years, Binyon belonged to a circle of artists, as a regular patron of the Wiener Cafe of London. His fellow intellectuals there were Ezra Pound, Sir William Rothenstein, Walter Sickert, Charles Ricketts, Lucien Pissarro and Edmund Dulac. Binyon’s reputation before the war was such that, on the death of the Poet Laureate Alfred Austin in 1913, Binyon was among the names mentioned in the press as his likely successor (others named included Thomas Hardy, John Masefield and Rudyard Kipling; the post went to Robert Bridges). For the Fallen Moved by the opening of the Great War and the already high number of casualties of the British Expeditionary Force, in 1914 Laurence Binyon wrote his For the Fallen, with its Ode of Remembrance, as he was visiting the cliffs on the north Cornwall coast, either at Polzeath or at Portreath (at each of which places there is a plaque commemorating the event, though Binyon himself mentioned Polzeath in a 1939 interview. The confusion may be related to Porteath Farm being near Polzeath). The piece was published by The Times newspaper in September, when public feeling was affected by the recent Battle of Marne. Today Binyon’s most famous poem, For the Fallen, is often recited at Remembrance Sunday services in the UK; is an integral part of Anzac Day services in Australia and New Zealand and of the 11 November Remembrance Day services in Canada. The third and fourth verses of the poem (although often just the fourth) have thus been claimed as a tribute to all casualties of war, regardless of nation. They went with songs to the battle, they were young. Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, We will remember them. They mingle not with their laughing comrades again; They sit no more at familiar tables of home; They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; They sleep beyond England’s foam Three of Binyon’s poems, including “For the Fallen”, were set by Sir Edward Elgar in his last major orchestra/choral work, The Spirit of England. In 1915, despite being too old to enlist in the First World War, Laurence Binyon volunteered at a British hospital for French soldiers, Hôpital Temporaire d’Arc-en-Barrois, Haute-Marne, France, working briefly as a hospital orderly. He returned in the summer of 1916 and took care of soldiers taken in from the Verdun battlefield. He wrote about his experiences in For Dauntless France (1918) and his poems, “Fetching the Wounded” and “The Distant Guns”, were inspired by his hospital service in Arc-en-Barrois. Artists Rifles, a CD audiobook published in 2004, includes a reading of For the Fallen by Binyon himself. The recording itself is undated and appeared on a 78 rpm disc issued in Japan. Other Great War poets heard on the CD include Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, David Jones and Edgell Rickword. Post-war life After the war, he returned to the British Museum and wrote numerous books on art; in particular on William Blake, Persian art, and Japanese art. His work on ancient Japanese and Chinese cultures offered strongly contextualised examples that inspired, among others, the poets Ezra Pound and W. B. Yeats. His work on Blake and his followers kept alive the then nearly-forgotten memory of the work of Samuel Palmer. Binyon’s duality of interests continued the traditional interest of British visionary Romanticism in the rich strangeness of Mediterranean and Oriental cultures. In 1931, his two volume Collected Poems appeared. In 1932, Binyon rose to be the Keeper of the Prints and Drawings Department, yet in 1933 he retired from the British Museum. He went to live in the country at Westridge Green, near Streatley (where his daughters also came to live during the Second World War). He continued writing poetry. In 1933–1934, Binyon was appointed Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. He delivered a series of lectures on The Spirit of Man in Asian Art, which were published in 1935. Binyon continued his academic work: in May 1939 he gave the prestigious Romanes Lecture in Oxford on Art and Freedom, and in 1940 he was appointed the Byron Professor of English Literature at University of Athens. He worked there until forced to leave, narrowly escaping the German invasion of Greece in April 1941 . He was succeeded by Lord Dunsany, who held the chair in 1940-1941. Binyon had been friends with Ezra Pound since around 1909, and in the 1930s the two became especially close; Pound affectionately called him “BinBin”, and assisted Binyon with his translation of Dante. Another protégé was Arthur Waley, whom Binyon employed at the British Museum. Between 1933 and 1943, Binyon published his acclaimed translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in an English version of terza rima, made with some editorial assistance by Ezra Pound. Its readership was dramatically increased when Paolo Milano selected it for the “The Portable Dante” in Viking’s Portable Library series. Binyon significantly revised his translation of all three parts for the project, and the volume went through three major editions and eight printings (while other volumes in the same series went out of print) before being replaced by the Mark Musa translation in 1981. At his death he was also working on a major three-part Arthurian trilogy, the first part of which was published after his death as The Madness of Merlin (1947). He died in Dunedin Nursing Home, Bath Road, Reading, on 10 March 1943 after an operation. A funeral service was held at Trinity College Chapel, Oxford, on 13 March 1943. There is a slate memorial in St. Mary’s Church, Aldworth, where Binyon’s ashes were scattered. On 11 November 1985, Binyon was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The inscription on the stone quotes a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Daughters His three daughters Helen, Margaret and Nicolete became artists. Helen Binyon (1904–1979) studied with Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious, illustrating many books for the Oxford University Press, and was also a marionettist. She later taught puppetry and published Puppetry Today (1966) and Professional Puppetry in England (1973). Margaret Binyon wrote children’s books, which were illustrated by Helen. Nicolete, as Nicolete Gray, was a distinguished calligrapher and art scholar. Bibliography of key works Poems and verse * Lyric Poems (1894) * Porphyrion and other Poems (1898) * Odes (1901) * Death of Adam and Other Poems (1904) * London Visions (1908) * England and Other Poems (1909) * “For The Fallen”, The Times, 21 September 1914 * Winnowing Fan (1914) * The Anvil (1916) * The Cause (1917) * The New World: Poems (1918) * The Idols (1928) * Collected Poems Vol 1: London Visions, Narrative Poems, Translations. (1931) * Collected Poems Vol 2: Lyrical Poems. (1931) * The North Star and Other Poems (1941) * The Burning of the Leaves and Other Poems (1944) * The Madness of Merlin (1947) In 1915 Cyril Rootham set “For the Fallen” for chorus and orchestra, first performed in 1919 by the Cambridge University Musical Society conducted by the composer. Edward Elgar set to music three of Binyon’s poems ("The Fourth of August", “To Women”, and “For the Fallen”, published within the collection “The Winnowing Fan”) as The Spirit of England, Op. 80, for tenor or soprano solo, chorus and orchestra (1917). English arts and myth * Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century (1895), Binyon’s first book on painting * John Crone and John Sell Cotman (1897) * William Blake: Being all his Woodcuts Photographically Reproduced in Facsimile (1902) * English Poetry in its relation to painting and the other arts (1918) * Drawings and Engravings of William Blake (1922) * Arthur: A Tragedy (1923) * The Followers of William Blake (1925) * The Engraved Designs of William Blake (1926) * Landscape in English Art and Poetry (1931) * English Watercolours (1933) * Gerard Hopkins and his influence (1939) * Art and freedom. (The Romanes lecture, delivered 25 May 1939). Oxford: The Clarendon press, (1939) Japanese and Persian arts * Painting in the Far East (1908) * Japanese Art (1909) * Flight of the Dragon (1911) * The Court Painters of the Grand Moguls (1921) * Japanese Colour Prints (1923) * The Poems of Nizami (1928) (Translation) * Persian Miniature Painting (1933) * The Spirit of Man in Asian Art (1936) Autobiography * For Dauntless France (1918) (War memoir) Biography * Botticelli (1913) * Akbar (1932) Stage plays * Brief Candles A verse-drama about the decision of Richard III to dispatch his two nephews * “Paris and Oenone”, 1906 * Godstow Nunnery: Play * Boadicea; A Play in eight Scenes * Attila: a Tragedy in Four Acts * Ayuli: a Play in three Acts and an Epilogue * Sophro the Wise: a Play for Children * (Most of the above were written for John Masefield’s theatre). * Charles Villiers Stanford wrote incidental music for Attila in 1907. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurence_Binyon

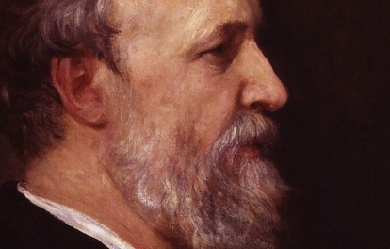

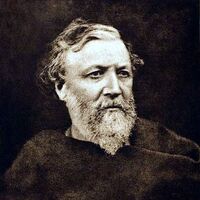

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father, who worked as a bank clerk, was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning's education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was fourteen. From fourteen to sixteen he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship.

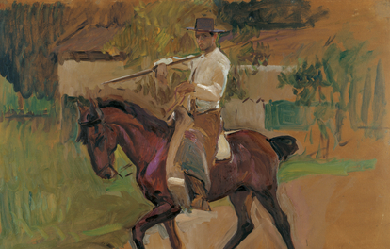

Gustavo Adolfo Domínguez Bastida (Sevilla, 17 de febrero de 1836 – Madrid, 22 de diciembre de 1870), más conocido como Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, fue un poeta y narrador español, perteneciente al movimiento del Romanticismo, aunque escribió en una etapa literaria perteneciente al Realismo. Por ser un romántico tardío, ha sido asociado igualmente con el movimiento posromántico. Aunque, mientras vivió, fue moderadamente conocido, sólo comenzó a ganar verdadero prestigio cuando, tras su muerte, fueron publicadas muchas de sus obras. Nació en Sevilla el 17 de febrero de 1836, hijo del pintor José Domínguez Insausti, que firmaba sus cuadros con el apellido de sus antepasados como José Domínguez Bécquer. Sus más conocidos trabajos son sus Rimas y Leyendas. Los poemas e historias incluidos en esta colección son esenciales para el estudio de la Literatura hispana, siendo ampliamente reconocidos por su influencia posterior. Gustavo Adolfo por Mercedes de Velilla En la margen del Betis murmurante, donde expira, entre flores, la onda inquieta, en monumento digno del poeta, su hermosa estatua se alzará triunfante. El sol le ofrecerá nimbo radiante; sus perfumes, la rosa y la violeta; la aurora, el beso de su luz discreta; el crepúsculo, brisa refrescante. Traerá la noche espíritus y hadas, visiones de Leyendas peregrinas que poblarán las verdes enramadas. La alondra y las obscuras golondrinas cantarán, al lucir las alboradas, las Rimas inmortales y divinas.

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (17 August 1840– 10 September 1922) (sometimes spelled “Wilfred”) was an English poet and writer. He and his wife, Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodlines through their farm, the Crabbet Arabian Stud. He was best known for his poetry, which was published in a collected edition in 1914, but also wrote a number of political essays and polemics. Blunt is also known for his views against imperialism, viewed as relatively enlightened for his time. Early life Blunt was born at Petworth House in Sussex and served in the Diplomatic Service from 1858 to 1869. He was raised in the faith of his mother, a Catholic convert, and educated at Twyford School, Stonyhurst, and at St Mary’s College, Oscott. His most memorable line of poetry on the subject comes from Satan Absolved (1899), where the devil, answering a Kiplingesque remark by God, snaps back: ‘The white man’s burden, Lord, is the burden of his cash’ Here, Longford explains, 'Blunt stood Rudyard Kipling’s familiar concept on its head, arguing that the imperialists’ burden is not their moral responsibility for the colonised peoples, but their urge to make money out of them.' Personal life In 1869, Blunt married Lady Anne Noel, the daughter of the Earl of Lovelace and Ada Lovelace, and granddaughter of Lord Byron. Together the Blunts travelled through Spain, Algeria, Egypt, the Syrian Desert, and extensively in the Middle East and India. Based upon pure-blooded Arabian horses they obtained in Egypt and the Nejd, they co-founded Crabbet Arabian Stud, and later purchased a property near Cairo, named Sheykh Obeyd which housed their horse breeding operation in Egypt. In 1882, he championed the cause of Urabi Pasha, which led him to be banned from entering Egypt for four years. Blunt generally opposed British imperialism as a matter of philosophy, and his support for Irish causes led to his imprisonment in 1888. Wilfrid and Lady Anne’s only child to live to maturity was Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth, later known as Lady Wentworth. As an adult, she was married in Cairo but moved permanently to the Crabbet Park Estate in 1904. Wilfrid had a number of mistresses, among them a long term relationship with the courtesan Catherine “Skittles” Walters, and the Pre-Raphaelite beauty, Jane Morris. Eventually, he moved another mistress, Dorothy Carleton, into his home. This event triggered Lady Anne’s legal separation from him in 1906. At that time, Lady Anne signed a Deed of Partition drawn up by Wilfrid. Under its terms, unfavourable to Lady Anne, she kept the Crabbet Park property (where their daughter Judith lived) and half the horses, while Blunt took Caxtons Farm, also known as Newbuildings, and the rest of the stock. Always struggling with financial concerns and chemical dependency issues, Wilfrid sold off numerous horses to pay debts and constantly attempted to obtain additional assets. Lady Anne left the management of her properties to Judith, and spent many months of every year in Egypt at the Sheykh Obeyd estate, moving there permanently in 1915. Due primarily to the manoeuvering of Wilfrid in an attempt to disinherit Judith and obtain the entire Crabbet property for himself, Judith and her mother were estranged at the time of Lady Anne’s death in 1917. As a result, Lady Anne’s share of the Crabbet Stud passed to Judith’s daughters, under the oversight of an independent trustee. Blunt filed a lawsuit soon afterward. Ownership of the Arabian horses went back and forth between the estates of father and daughter in the following years. Blunt sold more horses to pay off debts and shot at least four in an attempt to spite his daughter, an action which required intervention of the trustee of the estate with a court injunction to prevent him from further “dissipating the assets” of the estate. The lawsuit was settled in favour of the granddaughters in 1920, and Judith bought their share from the trustee, combining it with her own assets and reuniting the stud. Father and daughter briefly reconciled shortly before Wilfrid Scawen Blunt’s death in 1922, but his promise to rewrite his will to restore Judith’s inheritance never materialised. Blunt was a friend of Winston Churchill, aiding him in his 1906 biography of his father, Randolph Churchill, whom Blunt had befriended years earlier in 1883 at a chess tournament. Work in Africa In the early 1880s, Britain was struggling with its Egyptian colony. Wilfrid Blunt was sent to notify Sir Edward Malet, the British agent, as to the Egyptian public opinion concerning the recent changes in government and development policies. In mid-December 1881, Blunt met with Ahmed ‘Urabi, known as Arabi or 'El Wahid’ (the Only One) due to his popularity with the Egyptians. Arabi was impressed with Blunt’s enthusiasm and appreciation of his culture. Their mutual respect created an environment in which Arabi could peacefully explain the reasoning behind a new patriotic movement, 'Egypt for the Egyptians’. Over the course of several days, Arabi explained the complicated background of the revolutionaries and their determination to rid themselves of the Turkish oligarchy. Wilfrid Blunt was vital in the relay of this information to the British empire although his anti-imperialist views were disregarded and England mounted further campaigns in the Sudan in 1885 and 1896–98. Egyptian Garden scandal In 1901, a pack of fox hounds was shipped over to Cairo to entertain the army officers, and subsequently a foxhunt took place in the desert near Cairo. The fox was chased into Blunt’s garden, and the hounds and hunt followed it. As well as a house and garden, the land contained the Blunt’s Sheykh Obeyd stud farm, housing a number of valuable Arabian horses. Blunt’s staff challenged the trespassers– who, though army officers, were not in uniform– and beat them when they refused to turn back. For this, the staff were accused of assault against army officers and imprisoned. Blunt made strenuous efforts to free his staff, much to the embarrassment of the British army officers and civil servants involved. Bibliography * Sonnets and Songs. By Proteus. John Murray, 1875 * Aubrey de Vere (ed.): Proteus and Amadeus: A Correspondence Kegan Paul, 1878 * The Love Sonnets of Proteus. Kegan Paul, 1881 * The Future of Islam Kegan Paul, Trench, London 1882 * Esther (1892) * Griselda Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1893 * The Quatrains of Youth (1898) * Satan Absolved: A Victorian Mystery. J. Lane, London 1899 * Seven Golden Odes of Pagan Arabia (1903) * Atrocities of Justice under the English Rule in Egypt. T. F. Unwin, London 1907. * Secret History of the English Occupation of Egypt Knopf, 1907 * India under Ripon; A Private Diary T. Fisher Unwin, London 1909. * Gordon at Khartoum. S. Swift, London 1911. * The Land War in Ireland. S. Swift, London 1912 * The Poetical Works. 2 Vols. . Macmillan, London 1914 * My Diaries. Secker, London 1919; 2 Vols. Knopf, New York 1921 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilfrid_Scawen_Blunt