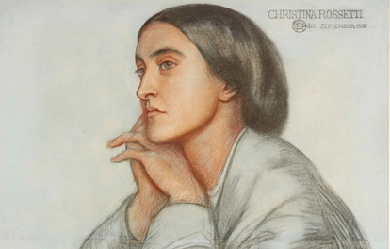

In 1830, Christina Rossetti was born in London, one of four children of Italian parents. Her father was the poet Gabriele Rossetti; her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti also became a poet and a painter. Rossetti’s first poems were written in 1842 and printed in the private press of her grandfather. In 1850, under the pseudonym Ellen Alleyne, she contributed seven poems to the Pre-Raphaelite journal The Germ, which had been founded by her brother William Michael and his friends.

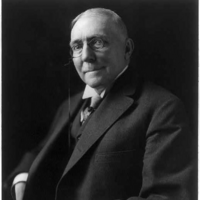

James Whitcomb Riley (October 7, 1849 – July 22, 1916) was an American writer, poet, and best-selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the "Hoosier Poet" and "Children's Poet" for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man". Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and created a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform. He became more popular in spite of the bad press he received, and as a result extricated himself from poorly negotiated contracts that limited his earnings; he quickly became very wealthy. Riley became a bestselling author in the 1890s. His children's poems were compiled into a book and illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy. Titled the Rhymes of Childhood, the book was his most popular and sold millions of copies. As a poet, Riley achieved an uncommon level of fame during his own lifetime. He was honored with annual Riley Day celebrations around the United States and was regularly called on to perform readings at national civic events. He continued to write and hold occasional poetry readings until a stroke paralyzed his right arm in 1910. Riley's chief legacy was his influence in fostering the creation of a midwestern cultural identity and his contributions to the Golden Age of Indiana Literature. Along with other writers of his era, he helped create a caricature of midwesterners and formed a literary community that produced works rivaling the established eastern literati. There are many memorials dedicated to Riley, including the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children. Family and background James Whitcomb Riley was born on October 7, 1849, in the town of Greenfield, Indiana, the third of the six children of Reuben Andrew and Elizabeth Marine Riley.[n 1] Riley's father was an attorney, and in the year before Riley's birth, he was elected a member of the Indiana House of Representatives as a Democrat. He developed a friendship with James Whitcomb, the governor of Indiana, after whom he named his son. Martin Riley, Riley's uncle, was an amateur poet who occasionally wrote verses for local newspapers. Riley was fond of his uncle who helped influence his early interest in poetry. Shortly after Riley's birth, the family moved into a larger house in town. Riley was "a quiet boy, not talkative, who would often go about with one eye shut as he observed and speculated." His mother taught him to read and write at home before sending him to the local community school in 1852. He found school difficult and was frequently in trouble. Often punished, he had nothing kind to say of his teachers in his writings. His poem "The Educator" told of an intelligent but sinister teacher and may have been based on one of his instructors. Riley was most fond of his last teacher, Lee O. Harris. Harris noticed Riley's interest in poetry and reading and encouraged him to pursue it further. Riley's school attendance was sporadic, and he graduated from grade eight at age twenty in 1869. In an 1892 newspaper article, Riley confessed that he knew little of mathematics, geography, or science, and his understanding of proper grammar was poor. Later critics, like Henry Beers, pointed to his poor education as the reason for his success in writing; his prose was written in the language of common people which spurred his popularity. Childhood influences Riley lived in his parents' home until he was twenty-one years old. At five years old he began spending time at the Brandywine Creek just outside Greenfield. His poems "The Barefoot Boy" and "The Old Swimmin' Hole" referred back to his time at the creek. He was introduced in his childhood to many people who later influenced his poetry. His father regularly brought home a variety of clients and disadvantaged people to give them assistance. Riley's poem "The Raggedy Man" was based on a German tramp his father hired to work at the family home. Riley picked up the cadence and character of the dialect of central Indiana from travelers along the old National Road. Their speech greatly influenced the hundreds of poems he wrote in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect. Riley's mother frequently told him stories of fairies, trolls, and giants, and read him children's poems. She was very superstitious, and influenced Riley with many of her beliefs. They both placed "spirit rappings" in their homes on places like tables and bureaus to capture any spirits that may have been wandering about. This influence is recognized in many of his works, including "Flying Islands of the Night." As was common at that time, Riley and his friends had few toys and they amused themselves with activities. With his mother's aid, Riley began creating plays and theatricals which he and his friends would practice and perform in the back of a local grocery store. As he grew older, the boys named their troupe the Adelphians and began to have their shows in barns where they could fit larger audiences. Riley wrote of these early performances in his poem "When We First Played 'Show'," where he referred to himself as "Jamesy." Many of Riley's poems are filled with musical references. Riley had no musical education, and could not read sheet music, but learned from his father how to play guitar, and from a friend how to play violin. He performed in two different local bands, and became so proficient on the violin he was invited to play with a group of adult Freemasons at several events. A few of his later poems were set to music and song, one of the most well known being A Short'nin' Bread Song—Pieced Out. When Riley was ten years old, the first library opened in his hometown. From an early age he developed a love of literature. He and his friends spent time at the library where the librarian read stories and poems to them. Charles Dickens became one Riley's favorites, and helped inspire the poems "St. Lirriper," "Christmas Season," and "God Bless Us Every One." Riley's father enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War, leaving his wife to manage the family home. While he was away, the family took in a twelve-year-old orphan named Mary Alice "Allie" Smith. Smith was the inspiration for Riley's poem "Little Orphant Annie". Riley intended to name the poem "Little Orphant Allie", but a typesetter's error changed the name of the poem during printing. Finding poetry Riley's father returned from the war partially paralyzed. He was unable to continue working in his legal practice and the family soon fell into financial distress. The war had a negative physiological effect on him, and his relationship with his family quickly deteriorated. He opposed Riley's interest in poetry and encouraged him to find a different career. The family finances finally disintegrated and they were forced to sell their town home in April 1870 and return to their country farm. Riley's mother was able to keep peace in the family, but after her death in August from heart disease, Riley and his father had a final break. He blamed his mother's death on his father's failure to care for her in her final weeks. He continued to regret the loss of his childhood home and wrote frequently of how it was so cruelly snatched from him by the war, subsequent poverty, and his mother's death. After the events of 1870, he developed an addiction to alcohol which he struggled with for the remainder of his life. Becoming increasingly belligerent toward his father, Riley moved out of the family home and briefly had a job painting houses before leaving Greenfield in November 1870. He was recruited as a Bible salesman and began working in the nearby town of Rushville, Indiana. The job provided little income and he returned to Greenfield in March 1871 where he started an apprenticeship to a painter. He completed the study and opened a business in Greenfield creating and maintaining signs. His earliest known poems are verses he wrote as clever advertisements for his customers. Riley began participating in local theater productions with the Adelphians to earn extra income, and during the winter months, when the demand for painting declined, Riley began writing poetry which he mailed to his brother living in Indianapolis. His brother acted as his agent and offered the poems to the newspaper Indianapolis Mirror for free. His first poem was featured on March 30, 1872 under the pseudonym "Jay Whit." Riley wrote more than twenty poems to the newspaper, including one that was featured on the front page. In July 1872, after becoming convinced sales would provide more income than sign painting, he joined the McCrillus Company based in Anderson, Indiana. The company sold patent medicines that they marketed in small traveling shows around Indiana. Riley joined the act as a huckster, calling himself the "Painter Poet". He traveled with the act, composing poetry and performing at the shows. After his act he sold tonics to his audience, sometimes employing dishonesty. During one stop, Riley presented himself as a formerly blind painter who had been cured by a tonic, using himself as evidence to encourage the audience to purchase his product. Riley began sending poems to his brother again in February 1873. About the same time he and several friends began an advertisement company. The men traveled around Indiana creating large billboard-like signs on the sides of buildings and barns and in high places that would be visible from a distance. The company was financially successful, but Riley was continually drawn to poetry. In October he traveled to South Bend where he took a job at Stockford & Blowney painting verses on signs for a month; the short duration of his job may have been due to his frequent drunkenness at that time. In early 1874, Riley returned to Greenfield to become a writer full-time. In February he submitted a poem entitled "At Last" to the Danbury News, a Connecticut newspaper. The editors accepted his poem, paid him for it, and wrote him a letter encouraging him to submit more. Riley found the note and his first payment inspiring. He began submitting poems regularly to the editors, but after the newspaper shut down in 1875, Riley was left without a paying publisher. He began traveling and performing with the Adelphians around central Indiana to earn an income while he searched for a new publisher. In August 1875 he joined another traveling tonic show run by the Wizard Oil Company. Newspaper work Riley began sending correspondence to the famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during late 1875 seeking his endorsement to help him start a career as a poet. He submitted many poems to Longfellow, whom he considered to be the greatest living poet. Not receiving a prompt response, he sent similar letters to John Townsend Trowbridge, and several other prominent writers askng for an endorsement. Longfellow finally replied in a brief letter, telling Riley that "I have read [the poems] in great pleasure, and think they show a true poetic faculty and insight." Riley carried the letter with him everywhere and, hoping to receive a job offer and to create a market for his poetry, he began sending poems to dozens of newspapers touting Longfellow's endorsement. Among the newspapers to take an interest in the poems was the Indianapolis Journal, a major Republican Party metropolitan newspaper in Indiana. Among the first poems the newspaper purchased from Riley were "Song of the New Year", "An Empty Nest", and a short story entitled "A Remarkable Man". The editors of the Anderson Democrat discovered Riley's poems in the Indianapolis Journal and offered him a job as a reporter in February 1877. Riley accepted. He worked as a normal reporter gathering local news, writing articles, and assisting in setting the typecast on the printing press. He continued to write poems regularly for the newspaper and to sell other poems to larger newspapers. During the year Riley spent working in Anderson, he met and began to court Edora Mysers. The couple became engaged, but terminated the relationship after they decided against marriage in August. After a rejection of his poems by an eastern periodical, Riley began to formulate a plot to prove his work was of good quality and that it was being rejected only because his name was unknown in the east. Riley authored a poem imitating the style of Edgar Allan Poe and submitted it to the Kokomo Dispatch under a fictitious name claiming it was a long lost Poe poem. The Dispatch published the poem and reported it as such. Riley and two other men who were part of the plot waited two weeks for the poem to be published by major newspapers in Chicago, Boston, and New York to gauge their reaction; they were disappointed. While a few newspapers believed the poem to be authentic, the majority did not, claiming the quality was too poor to be authored by Poe. An employee of the Dispatch learned the truth of the incident and reported it to the Kokomo Tribune, which published an expose that outed Riley as a conspirator behind the hoax. The revelation damaged the credibility of the Dispatch and harmed Riley's reputation. In the aftermath of the Poe plot, Riley was dismissed from the Democrat, so he returned to Greenfield to spend time writing poetry. Back home, he met Clara Louise Bottsford, a school teacher boarding in his father's home. They found they had much in common, particularly their love of literature. The couple began a twelve-year intermittent relationship which would be Riley's longest lasting. In mid-1878 the couple had their first breakup, caused partly by Riley's alcohol addiction. The event led Riley to make his first attempt to give up liquor. He joined a local temperance organization, but quit after a few weeks. Performing poet Without a steady income, his financial situation began to deteriorate. He began submitting his poems to more prominent literary magazines, including Scribner's Monthly, but was informed that although he showed promise, his work was still short of the standards required for use in their publications. Locally, he was still dealing with the stigma of the Poe plot. The Indianapolis Journal and other newspapers refused to accept his poetry, leaving Riley desperate for income. In January 1878 on the advice of a friend, Riley paid an entrance fee to join a traveling lecture circuit where he could give poetry readings. In exchange, he received a portion of the profit his performances earned. Such circuits were popular at the time, and Riley quickly earned a local reputation for his entertaining readings. In August 1878, Riley followed Indiana Governor James D. Williams as speaker at a civic event in a small town near Indianapolis. He recited a recently composed poem, "A Childhood Home of Long Ago," telling of life in pioneer Indiana. The poem was well received and was given good reviews by several newspapers. "Flying Islands of the Night" is the only play that Riley wrote and published. Authored while Riley was traveling with the Adelphians, but never performed, the play has similarities to A Midsummer Night's Dream, which Riley may have used as a model. Flying Islands concerns a kingdom besieged by evil forces of a sinister queen who is defeated eventually by an angel-like heroine. Most reviews were positive. Riley published the play and it became popular in the central Indiana area during late 1878, helping Riley to convince newspapers to again accept his poetry. In November 1879 he was offered a position as a columnist at the Indianapolis Journal and accepted after being encouraged by E.B. Matindale, the paper's chief editor. Although the play and his newspaper work helped expose him to a wider audience, the chief source of his increasing popularity was his performances on the lecture circuit. He made both dramatic and comedic readings of his poetry, and by early 1879 could guarantee large crowds whenever he performed. In an 1894 article, Hamlin Garland wrote that Riley's celebrity resulted from his reading talent, saying "his vibrant individual voice, his flexible lips, his droll glance, united to make him at once poet and comedian—comedian in the sense in which makes for tears as well as for laughter." Although he was a good performer, his acts were not entirely original in style; he frequently copied practices developed by Samuel Clemens and Will Carleton. His tour in 1880 took him to every city in Indiana where he was introduced by local dignitaries and other popular figures, including Maurice Thompson with whom he began to develop a close friendship. Developing and maintaining his publicity became a constant job, and received more of his attention as his fame grew. Keeping his alcohol addiction secret, maintaining the persona of a simple rural poet and a friendly common person became most important. Riley identified these traits as the basis of his popularity during the mid-1880s, and wrote of his need to maintain a fictional persona. He encouraged the stereotype by authoring poetry he thought would help build his identity. He was aided by editorials he authored and submitted to the Indianapolis Journal offering observations on events from his perspective as a "humble rural poet". He changed his appearance to look more mainstream, and began by shaving his mustache off and abandoning the flamboyant dress he employed in his early circuit tours. By 1880 his poems were beginning to be published nationally and were receiving positive reviews. "Tom Johnson's Quit" was carried by newspapers in twenty states, thanks in part to the careful cultivation of his popularity. Riley became frustrated that despite his growing acclaim, he found it difficult to achieve financial success. In the early 1880s, in addition to his steady performing, Riley began producing many poems to increase his income. Half of his poems were written during the period. The constant labor had adverse effects on his health, which was worsened by his drinking. At the urging of Maurice Thompson, he again attempted to stop drinking liquor, but was only able to give it up for a few months. Politics In March 1888, Riley traveled to Washington, D.C. where he had dinner at the White House with other members of the International Copyright League and President of the United States Grover Cleveland. Riley made a brief performance for the dignitaries at the event before speaking about the need for international copyright protections. Cleveland was enamored by Riley's performance and invited him back for a private meeting during which the two men discussed cultural topics. In the 1888 Presidential Election campaign, Riley's acquaintance Benjamin Harrison was nominated as the Republican candidate. Although Riley had shunned politics for most of his life, he gave Harrison a personal endorsement and participated in fund-raising events and vote stumping. The election was exceptionally partisan in Indiana, and Riley found the atmosphere of the campaign stressful; he vowed never to become involved with politics again. Upon Harrison's election, he suggested Riley be named the national poet laureate, but Congress failed to act on the request. Riley was still honored by Harrison and visited him at the White House on several occasions to perform at civic events. Pay problems and scandal Riley and Nye made arrangements with James Pond to make two national tours during 1888 and 1889. The tours were popular and generally sold out, with hundreds having to be turned away. The shows were usually forty-five minutes to an hour long and featured Riley reading often humorous poetry interspersed by stories and jokes from Nye. The shows were informal and the two men adjusted their performances based on their audiences reactions. Riley memorized forty of his poems for the shows to add to his own versatility. Many prominent literary and theatrical people attended the shows. At a New York City show in March 1888, Augustin Daly was so enthralled by the show he insisted on hosting the two men at a banquet with several leading Broadway theatre actors. Despite Riley serving as the act's main draw, he was not permitted to become an equal partner in the venture. Nye and Pond both received a percentage of the net profit, while Riley was paid a flat rate for each performance. In addition, because of Riley's past agreements with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, he was required to pay half of his fee to his agent Amos Walker. This caused the other men to profit more than Riley from his own work. To remedy this situation, Riley hired his brother-in-law Henry Eitel, an Indianapolis banker, to manage his finances and act on his behalf to try and extricate him from his contract. Despite discussions and assurances from Pond that he would work to address the problem, Eitel had no success. Pond ultimately made the situation worse by booking months of solid performances, not allowing Riley and Nye a day of rest. These events affected Riley physically and emotionally; he became despondent and began his worst period of alcoholism. During November 1889, the tour was forced to cancel several shows after Riley became severely inebriated at a stop in Madison, Wisconsin. Walker began monitoring Riley and denying him access to liquor, but Riley found ways to evade Walker. At a stop at the Masonic Temple Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky, in January 1890, Riley paid the hotel's bartender to sneak whiskey to his room. He became too drunk to perform, and was unable to travel to the next stop. Nye terminated the partnership and tour in response. The reason for the breakup could not be kept secret, and hotel staff reported to the Louisville Courier-Journal that they saw Riley in a drunken stupor walking around the hotel. The story made national news and Riley feared his career was ruined. He secretly left Louisville at night and returned to Indianapolis by train. Eitel defended Riley to the press in an effort to gain sympathy for Riley, explaining the abusive financial arrangements his partners had made. Riley however refused to speak to reporters and hid himself for weeks. Much to Riley's surprise, the news reports made him more popular than ever. Many people thought the stories were exaggerated, and Riley's carefully cultivated image made it difficult for the public to believe he was an alcoholic. Riley had stopped sending poetry to newspapers and magazines in the aftermath, but they soon began corresponding with him requesting that he resume writing. This encouraged Riley, and he made another attempt to give up liquor as he returned to his public career. The negative press did not end however, as Nye and Pond threatened to sue Riley for causing their tour to end prematurely. They claimed to have lost $20,000. Walker threatened a separate suit demanding $1,000. Riley hired Indianapolis lawyer William P. Fishback to represent him and the men settled out of court. The full details of the settlement were never disclosed, but whatever the case, Riley finally extricated himself from his old contracts and became a free agent. The exorbitant amount Riley was being sued for only reinforced public opinion that Riley had been mistreated by his partners, and helped him maintain his image. Nye and Riley remained good friends, and Riley later wrote that Pond and Walker were the source of the problems. Riley's poetry had become popular in Britain, in large part due to his book Old-Fashioned Roses. In May 1891 he traveled to England to make a tour and what he considered a literary pilgrimage. He landed in Liverpool and traveled first to Dumfries, Scotland, the home and burial place of Robert Burns. Riley had long been compared to Burns by critics because they both used dialect in their poetry and drew inspiration from their rural homes. He then traveled to Edinburgh, York, and London, reciting poetry for gatherings at each stop. Augustin Daly arranged for him to give a poetry reading to prominent British actors in London. Riley was warmly welcomed by its literary and theatrical community and he toured places that Shakespeare had frequented. Riley quickly tired of traveling abroad and began longing for home, writing to his nephew that he regretted having left the United States. He curtailed his journey and returned to New York City in August. He spent the next months in his Greenfield home attempting to write an epic poem, but after several attempts gave up, believing he did not possess the ability. By 1890, Riley had authored almost all of his famous poems. The few poems he did write during the 1890s were generally less well received by the public. As a solution, Riley and his publishers began reusing poetry from other books and printing some of his earliest works. When Neighborly Poems was published in 1891, a critic working for the Chicago Tribune pointed out the use of Riley's earliest works, commenting that Riley was using his popularity to push his crude earlier works onto the public only to make money. Riley's newest poems published in the 1894 book Armazindy received very negative reviews that referred to poems like "The Little Dog-Woggy" and "Jargon-Jingle" as "drivel" and to Riley as a "worn out genius." Most of his growing number of critics suggested that he ignored the quality of the poems for the sake of making money. National poet Riley had become very wealthy by the time he ended touring in 1895, and was earning $1,000 a week. Although he retired, he continued to make minor appearances. In 1896, Riley performed four shows in Denver. Most of the performances of his later life were at civic celebrations. He was a regular speaker at Decoration Day events and delivered poetry before the unveiling of monuments in Washington, D.C. Newspapers began referring to him as the "National Poet", "the poet laureate of America", and "the people's poet laureate". Riley wrote many of his patriotic poems for such events, including "The Soldier", "The Name of Old Glory", and his most famous such poem, "America!". The 1902 poem "America, Messiah of Nations" was written and read by Riley for the dedication of the Indianapolis Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. The only new poetry Riley published after the end of the century were elegies for famous friends. The poetic qualities of the poems were often poor, but they contained many popular sentiments concerning the deceased. Among those he eulogized were Benjamin Harrison, Lew Wallace, and Henry Lawton. Because of the poor quality of the poems, his friends and publishers requested that he stop writing them, but he refused. In 1897, Riley's publishers suggested that he create a multi-volume series of books containing his complete life works. With the help of his nephew, Riley began working to compile the books, which eventually totaled sixteen volumes and were finally completed in 1914. Such works were uncommon during the lives of writers, attesting to the uncommon popularity Riley had achieved. His works had become staples for Ivy League literature courses and universities began offering him honorary degrees. The first was Yale in 1902, followed by a Doctorate of Letters from the University of Pennsylvania in 1904. Wabash College and Indiana University granted him similar awards. In 1908 he was elected member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1912 they conferred upon him a special medal for poetry. Riley was influential in helping other poets start their careers, having particularly strong influences on Hamlin Garland, William Allen White, and Edgar Lee Masters. He discovered aspiring African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1892. Riley thought Dunbar's work was "worthy of applause", and wrote him letters of recommendation to help him get his work published. Declining health In 1901, Riley's doctor diagnosed him with neurasthenia, a nervous disorder, and recommended long periods of rest as a cure.[173] Riley remained ill for the rest of his life and relied on his landlords and family to aid in his care. During the winter months he moved to Miami, Florida, and during summer spent time with his family in Greenfield. He made only a few trips during the decade, including one to Mexico in 1906. He became very depressed by his condition, writing to his friends that he thought he could die at any moment, and often used alcohol for relief.[174] In March 1909, Riley was stricken a second time with Bell's palsy, and partial deafness, the symptoms only gradually eased over the course of the year.[175] Riley was a difficult patient, and generally refused to take any medicine except the patent medicines he had sold in his earlier years; the medicines often worsened his conditions, but his doctors could not sway his opinion.[176] On July 10, 1910 he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping for a quick recovery, his family kept the news from the press until September. Riley found the loss of use of his writing hand the worst part of the stroke, which served only to further depress him.[174][177] With his health so poor, he decided to work on a legacy by which to be remembered in Indianapolis. In 1911 he donated land and funds to build a new library on Pennsylvania Avenue.[178] By 1913, with the aid of a cane, Riley began to recover his ability to walk. His inability to write, however, nearly ended his production of poems. George Ade worked with him from 1910 through 1916 to write his last five poems and several short autobiographical sketches as Riley dictated. His publisher continued recycling old works into new books, which remained in high demand.[178] Since the mid-1880s, Riley had been the nation's most read poet, a trend that accelerated at the turn of the century. In 1912 Riley recorded readings of his most popular poetry to be sold by Victor Records. Riley was the subject of three paintings by T. C. Steele. The Indianapolis Arts Association commissioned a portrait of Riley to be created by world famous painter John Singer Sargent. Riley's image became a nationally known icon and many businesses capitalized on his popularity to sell their products; Hoosier Poet brand vegetables became a major trade-name in the midwest.[179] In 1912, the governor of Indiana instituted Riley Day on the poet's birthday. Schools were required to teach Riley's poems to their children, and banquet events were held in his honor around the state. In 1915 and 1916 the celebration was national after being proclaimed in most states. The annual celebration continued in Indiana until 1968.[180] In early 1916 Riley was filmed as part of a movie to celebrate Indiana's centennial, the video is on display at the Indiana State Library.[181][182] Death and legacy On July 22, 1916, Riley suffered a second stroke. He recovered enough during the day to speak and joke with his companions. He died before dawn the next morning, July 23.[183] Riley's death shocked the nation and made front page headlines in major newspapers.[184] President Woodrow Wilson wrote a brief note to Riley's family offering condolences on behalf the entire nation. Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston offered to allow Riley to lie in state at the Indiana Statehouse—Abraham Lincoln being the only other person to have previously received such an honor.[185] During the ten hours he lay in state on July 24, more than thirty-five thousand people filed past his bronze casket; the line was still miles long at the end of the day and thousands were turned away. The next day a private funeral ceremony was held and attended by many dignitaries. A large funeral procession then carried him to Crown Hill Cemetery where he was buried in a tomb at the top of the hill, the highest point in the city of Indianapolis.[186] Within a year of Riley's death many memorials were created, including several by the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association. The James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children was created and named in his honor by a group of wealthy benefactors and opened in 1924. In the following years, other memorials intended to benefit children were created, including Camp Riley for youth with disabilities.[187][188] The memorial foundation purchased the poet's Lockerbie home in Indianapolis and it is now maintained as a museum. The James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home is the only late-Victorian home in Indiana that is open to the public and the United States' only late-Victorian preservation, featuring authentic furniture and decor from that era. His birthplace and boyhood home, now the James Whitcomb Riley House, is preserved as a historical site.[189] A Liberty ship, commissioned April 23, 1942, was christened the SS James Whitcomb Riley. It served with the United States Maritime Commission until being scrapped in 1971. James Whitcomb Riley High School opened in South Bend, Indiana in 1924. In 1950, there was a James Whitcomb Riley Elementary School in Hammond, Indiana, but it was torn down in 2006. East Chicago, Indiana had a Riley School at one time, as did neighboring Gary, Indiana and Anderson, Indiana. One of New Castle, Indiana's elementary schools is named for Riley as is the road on which it is located. The former Greenfield High School was converted to Riley Elementary School and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 10-cent stamp honoring Riley.[190] As a lasting tribute, the citizens of Greenfield hold a festival every year in Riley's honor. Taking place the first or second weekend of October, the "Riley Days" festival traditionally commences with a flower parade in which local school children place flowers around Myra Reynolds Richards' statue of Riley on the county courthouse lawn, while a band plays lively music in honor of the poet. Weeks before the festival, the festival board has a queen contest. The 2010–2011 queen was Corinne Butler. The pageant has been going on many years in honor of the Hoosier poet[191] According to historian Elizabeth Van Allen, Riley was instrumental in helping form a midwestern cultural identity. The midwestern United States had no significant literary community before the 1880s.[192] The works of the Western Association of Writers, most notably those of Riley and Wallace, helped create the midwest's cultural identity and create a rival literary community to the established eastern literari. For this reason, and the publicity Riley's work created, he was commonly known as the "Hoosier Poet." Critical reception and style Riley was among the most popular writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, known for his "uncomplicated, sentimental, and humorous" writing.[195] Often writing his verses in dialect, his poetry caused readers to recall a nostalgic and simpler time in earlier American history. This gave his poetry a unique appeal during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the United States. Riley was a prolific writer who "achieved mass appeal partly due to his canny sense of marketing and publicity."[195] He published more than fifty books, mostly of poetry and humorous short stories, and sold millions of copies.[195] Riley is often remembered for his most famous poems, including the "The Raggedy Man" and "Little Orphant Annie". Many of his poems, including those, where partially autobiographical, as he used events and people from his childhood as an inspiration for subject matter.[195] His poems often contained morals and warnings for children, containing messages telling children to care for the less fortunate of society. David Galens and Van Allen both see these messages as Riley's subtle response to the turbulent economic times of the Gilded Age and the growing progressive movement.[196] Riley believed that urbanization robbed children of their innocence and sincerity, and in his poems he attempted to introduce and idolize characters who had not lost those qualities.[197] His children's poems are "exuberant, performative, and often display Riley's penchant for using humorous characterization, repetition, and dialect to make his poetry accessible to a wide-ranging audience."[195][198] Although hinted at indirectly in some poems, Riley wrote very little on serious subject matter, and actually mocked attempts at serious poetry. Only a few of his sentimental poems concerned serious subjects. "Little Mandy's Christmas-Tree", "The Absence of Little Wesley", and "The Happy Little Cripple" were about poverty, the death of a child, and disabilities. Like his children's poems, they too contained morals, suggesting society should pity the downtrodden and be charitable.[195][198] Riley wrote gentle and romantic poems that were not in dialect. They generally consisted of sonnets and were strongly influenced by the works of John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His standard English poetry was never as popular as his Hoosier dialect poems.[195] Still less popular were the poems Riley authored in his later years; most were to commemorate important events of American history and to eulogize the dead.[195] Riley's contemporaries acclaimed him "America's best-loved poet".[195][198] In 1920, Henry Beers lauded the works of Riley "as natural and unaffected, with none of the discontent and deep thought of cultured song."[195] Samuel Clemens, William Dean Howells, and Hamlin Garland, each praised Riley's work and the idealism he expressed in his poetry. Only a few critics of the period found fault with Riley's works. Ambrose Bierce criticized Riley for his frequent use of dialect. Bierce accused Riley of using dialect to "cover up [the] faulty construction" of his poems.[195] Edgar Lee Masters found Riley's work to be superficial, claiming it lacked irony and that he had only a "narrow emotional range".[195] By the 1930s popular critical opinion towards Riley's works began to shift in favor of the negative reviews. In 1951, James T. Farrell said Riley's works were "cliched." Galens wrote that modern critics consider Riley to be a "minor poet, whose work—provincial, sentimental, and superficial though it may have been—nevertheless struck a chord with a mass audience in a time of enormous cultural change."[195] Thomas C. Johnson wrote that what most interests modern critics was Riley's ability to market his work, saying he had a unique understanding of "how to commodify his own image and the nostalgic dreams of an anxious nation."[195] Among the earliest widespread criticisms of Riley were opinions that his dialect writing did not actually represent the true dialect of central Indiana. In 1970 Peter Revell wrote that Riley's dialect was more similar to the poor speech of a child rather than the dialect of his region. Revell made extensive comparison to historical texts and Riley's dialect usage. Philip Greasley wrote that that while "some critics have dismissed him as sub-literary, insincere, and an artificial entertainer, his defenders reply that an author so popular with millions of people in different walks of life must contribute something of value, and that his faults, if any, can be ignored." References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Whitcomb_Riley

[b.] September 25, 1974, Tempe, AZ; [p.] Mr. Phil and Barbara K. Ransopher; [ed.] Bachelor of Arts in English (Language and Lit.); [occ.] library assistant, writer, editor; [memb.] Yahoo Groups: Appreciating Poetry (owner), Erotica Gallery (owner), Ex BBC Poetry Group (moderator), AATNAANPT (An All Totally New An All New Poetry Thread), Adult Amatuer (sic) Writers Emporium; [hon.] November 19, 2010 Poetic Skies Poem Of The Week (Her Love Has A Cold Wet Nose), May 15, 2015, First weekly winner for Fortune Poets group A Soldier's Fortune, 2015 Poet of the year for Fortune Poets; [pers.] I write what I see in my mind, what I feel in my heart, and what I know in my soul; [a.] Garland, TX

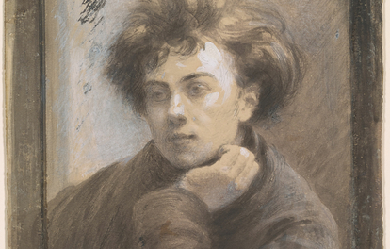

Arthur Rimbaud est un poète français, né le 20 octobre 1854 à Charleville et mort le 10 novembre 1891 à Marseille. Bien que brève, la densité de son œuvre poétique fait d'Arthur Rimbaud une des figures premières de la littérature française. Rimbaud écrit ses premiers poèmes à 15 ans. Selon lui, le poète doit être « voyant » et « il faut être absolument moderne ». Il entretient une aventure amoureuse tumultueuse avec le poète Paul Verlaine. À l'âge de vingt ans, il renonce subitement à l’écriture, sans avoir encore été véritablement publié, pour se consacrer davantage à la lecture, ainsi qu'à la poursuite de sa pratique des langues.

I am very passionate about writing especially poetry because it speaks to my soul. I'm looking forward to become a professional writer someday and get published. I want to share my writing talent worldwide and I won't stop until I do. While I'm here at "Poeticous". I would like to receive honest feedback on my writings, but I can see people don't really comment, they only view. So what's the point of Poet's like myself sharing our poetry? if no one is willing to comment. Also, they may like the poem but refuse to press the "like" button..........I just don't understand that!!!

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882) was an English poet, illustrator, painter and translator. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, and was later to be the main inspiration for a second generation of artists and writers influenced by the movement, most notably William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. His work also influenced the European Symbolists and was a major precursor of the Aesthetic movement.

Welcome to my poetry page, I think its a blast, Some of my Poetry is about my past. Lots of wonderful words are written and funny, I don't get paid so it wont cost you money. My poems are of the wonders of life someone said I have written about the dead. Some people may be offended by some of my rhymes, So if your offended don't come back to read next time. But if my poetry makes you laugh please come back, Because this Yorkshire man has a sense of humour and can be really daft.

José Eustasio Rivera Salas (February 19, 1888 - December 1, 1928) was a Colombian lawyer and poet primarily known for his national epic The Vortex. José Eustasio Rivera was born on February 19, 1888 in Aguas Calientes, a hamlet of the city of Neiva, later that year the hamlet was incorporated into the newly created municipality of San Mateo, which was later renamed Rivera in honour of José Eustasio. His parents were Eustasio Rivera Escobar and Catalina Salas, and he was the first boy and fifth child out of eleven children, out of which eight made into adulthood, José Eustasio, Luis Enrique, Margarita, Virginia, Laura, Susana, Julia and Ernestina.[1] In spite of his family's economic situation, he received a catholic education thanks to the help of other relatives and his own efforts. He attended Santa Librada school in Neiva and San Luis Gonzaga in Elías. In 1906 he received a scholarship to study at the normal school in Bogotá. In 1909, after graduating, he moved to Ibagué where he worked as a school inspector. In 1912 he enrolled at the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of National University, graduating as a lawyer in 1917. Career After a failed attempt to be elected for the senate, he was appointed Legal Secretary of the Colombo-Venezuelan Border Commission to determine the limits with Venezuela, there he had the opportunity to travel through the Colombian jungles, rivers, and mountains, giving him a first hand experience of the subjects he would later write. Disappointed with the lack of resources offered by his government for his trip, he abandoned the commission and continued travelling on his own. He later rejoined the commission, but before that he went to Brazil, where he became acquainted with the work of important Brazilian writers of his time, particularly Euclides da Cunha. In this venture he became familiar with life in the Colombian plains and with problems related to the extraction of rubber in the Amazon jungle, a matter that would be central in his major work, La vorágine (1924) (translated as The Vortex), now considered one of the most important novels in Latin American literary history. To write this novel he read extensively about the situation of rubber workers in the Amazon basin. After the success of his novel, he was elected, in 1925, as a member for the Investigative Commission for Exterior Relations and Colonization. He also published several articles in newspapers in Colombia. In these pieces, he criticized irregularities in government contracts, and denounced the abandonment of the rubber areas of Colombia and the mistreatment of workers. He also publicly defended his novel, which had been criticized by some Colombian literary critics as being too poetic. This criticism would be largely silenced by the wide praise the novel was receiving everywhere else. Death Rivera had arrived in New York the last week of April 1928 in the hopes of translating his novel into English, publishing it in the United States, and turning it into a motion picture film with the goal of exporting Colombian culture abroad. His venture, albeit riffled with difficulties, was moving along when on November 27 he suffered an attack of seizures and was taken to the Stuyvesant Polyclinic Hospital where he remained for four days in a comatose state until his death on December 1, 1928. After his death, his body was transported by ship from New York to Barranquilla on the United Fruit Company's ship the Sixaola. At his arrival on port, his body was transported in procession to the Pro-Cathedral of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino where a requiem mass was given and the body laid in chapelle ardente. The casket then made its way down the Magdalena onto Bogotá on the mail steamship Carbonell González, arriving in Girardot and finishing by train to arrive in Bogotá on January 7, 1929 and was taken directly to the Capitolio Nacional where it was placed lying in state for public viewing. His body was finally laid to rest in the Central Cemetery of Bogotá on January 19. Selected works * La Vorágine [The Vortex]. Bogotá: Pontifical Xavierian University. [1924]. * Tierra de Promisión [Promised Land]. Bogotá: Pontifical Xavierian University. [1921]. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/José_Eustasio_Rivera

Lonnie Rutledge is a prolific artist, songwriter, and poet from the United States. He is known for his peculiar methods, intense concepts, experimental writing and often demented production. He has described his style as 'Schizodelic'; a term he is noted for coining in the mid 1990's. Lxnnnie has released many albums under assorted aliases in multiple genres of music. He has had songs featured in major motion pictures, produced music for a number of commercials, designed album covers and published a book of poetry.

José Antonio Ramos Sucre poeta, educador y diplomático venezolano. Considerado uno de los más destacados escritores e intelectuales de la historia literaria del país. Primeros años Nace en Cumaná Edo. Sucre el 9 de junio de 1890. Hijo de Jerónimo Ramos Martínez y de Rita Sucre Mora, sobrina del Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho Antonio José de Sucre. Aprende sus primeras letras en Cumaná en la escuela Don Jacinto Alarcón. En 1900 es enviado a Carúpano para ser educado por su padrino y tio paterno, el historiador y letrado, presbitero Jose Antonio Ramos Martinez, quien lo inicia en el latín y los libros, pero también lo aparta de los juegos infantiles. En 1902 muere su padre. En 1903 después de la muerte del tio regresa a su hogar en Cumaná. Estudios En su ciudad natal estudia en el Colegio Nacional de Cumaná, hoy Liceo Antonio Jose de Sucre, dirigido entonces por Don José Silverio González Varela. En 1908, por sus dotes excepcionales, es nombrado su asistente. En 1910 se gradúa de bachiller en Filosofía, viajando de inmediato a Caracas para iniciar en la Universidad Central de Venezuela sus estudios de Derecho y Literatura y continuar aprendiendo idiomas (griego antiguo y moderno, francés, inglés, italiano, portugués, alemán, danés, sueco y sánscrito). Al ser cerrada la universidad por el gobierno del General Juan Vicente Gómez, se ve obligado a continuar los estudios por su cuenta. Graduado de abogado en la UCV en 1917 y posteriormente de Doctor en Leyes en 1925, no ejerce esta profesión sino que se gana la vida como profesor de Historia y Geografía Universal, Historia y Geografía de Venezuela, Latín y Griego, en liceos de educación media, como el Liceo Caracas, hoy llamado Liceo Andrés Bello. Asimismo desde 1914 trabaja como intérprete y traductor en la Cancillería. Escritos Desde 1911 se da a conocer como poeta publicando en casi todas las revistas y diarios, sobre todo en El Universal, donde aparecieron al menos 108 de sus poemas en prosa. Reúne su obra en Trizas de papel (1921), Sobre las huellas de Humboldt (1923), ambos integrados a La Torre de Timón (1925), en 1929 publica juntos dos libros distintos, Las formas del fuego y El cielo de esmalte. Hombre de carácter solitario e introvertido, se dedica al estudio y a la lectura, así como a su obra poética, pero su labor intelectual es seriamente perturbada por una enfermedad nerviosa que se manifiesta en un frecuente estado de insomnio. En ese estado febril recorre las calles de la ciudad en horas nocturnas. En sus textos expresa el sufrimiento que le produce su cada vez más pronunciada fatiga mental. Afirma que el contexto artístico e intelectual venezolano es mediocre, retórico y conformista, apegado a formas estéticas degradadas. Contra esto, Ramos Sucre innova en el campo de la poesía al ser uno de los primeros venezolanos en cultivar el poema en prosa, así como el uso de varias voces poéticas en lugar del "yo" único e inmutable. Muerte El 13 de junio de 1930 durante un viaje diplomático en la ciudad de Ginebra, se suicida al tomar una sobredosis de veronal. Su obra, al no poder ser catalogada dentro de las corrientes literarias de su tiempo, no será tomada en cuenta hasta casi medio siglo después, cuando se le reconoce como uno de los poetas más originales y avanzados de siglo XX venezolano. Sus cartas y otros escritos son publicados mucho después de su muerte, en un volumen titulado Los aires del presagio. Su poesía en muchas ocasiones ha sido calificada de "pre-vanguardista", de hecho, colaboró con el único número de la revista Válvula, uno de los principales órganos de la vanguardia del país. Salvo la coincidencia temporal con otros autores de la misma época, la obra de Ramos Sucre no puede clasificarse en un movimiento determinado. son los escritores de los grupos Sardio y El techo de la ballena los que, durante la década de los 60, rescatan su obra y la dan a conocer como una poesía que desafía la división rígida del género. En 2006, el escritor venezolano Rubi Guerra recibió el Premio de Novela Corta Rufino Blanco Fombona por su novela La tarea del testigo (Caracas: Fundación Editorial El perro y la rana, 2007), basada en los últimos meses de Ramos Sucre en Europa. Referencias Wikipedia—http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/José_Antonio_Ramos_Sucre

Silvio Rodríguez Domínguez (San Antonio de los Baños, 29 de noviembre de 1946) es un cantautor, guitarrista y poeta cubano, exponente característico de la música de su país surgida con la Revolución cubana, conocida como la Nueva Trova Cubana. Con más de cuatro décadas de carrera musical, ha escrito al menos quinientas cuarenta y ocho canciones y publicado una veintena de álbumes, siendo uno de los cantautores de mayor trascendencia internacional del habla hispana.

Alfonso Reyes Ochoa (Monterrey, 17 de mayo de 1889 - México, D.F., 27 de diciembre de 1959) fue un poeta, ensayista, narrador, diplomático y pensador mexicano. Se le conoce también como «el regiomontano universal». Fue el noveno de los doce hijos del general Bernardo Reyes y de doña Aurelia Ochoa. Su padre ocupó importantes cargos durante los gobiernos de Porfirio Díaz (fue gobernador del estado de Nuevo León y Secretario de Guerra y Marina). Alfonso Reyes es un escritor clásico, formalista, comedido, su prosa nos hace pensar en el modelo apolíneo de Nietzsche. Sus temas y preocupaciones fueron siempre los grandes temas de la cultura clásica griega. Fue considerado por Borges “el mejor prosista del idioma español del siglo XX”.

Edwin Arlington Robinson (December 22, 1869—April 6, 1935) was an American poet who won three Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was born in Head Tide, Lincoln County, Maine but his family moved to Gardiner, Maine in 1871. He described his childhood in Maine as “stark and unhappy”: His parents (who had wanted a girl) did not name him until he was six months old, when they visited a holiday resort—whereupon, other vacationers decided that he should have a name and selected a man from Arlington, Massachusetts to draw a name out of a hat. Throughout his life, he not only hated his given name, but also his family’s habit of calling him “Win.” As an adult, he always used the signature “E. A.”

I am a believing and practicing Christian. I study God's word daily. I write Christian poetry but I also write on other topics. My poems are very simple. I don't use fancy or big words so this may be disappointing to some. I love the old Classic Poets like Sara Teasdale, Robert Louis Stevenson, and a whole host of others. I love all kinds of music from hard rock to classical. I'd like to share a few quotes, sorry I do not have all the names of the authors; Never allow someone to be your priority while allowing yourself to be their option” “A woman often thinks she regrets the lover, when she only regrets the love” By Francois de la Rochefoucauld “One of the hardest things in life is watching the person you love, love someone else.” “The one that seems to love the least, has the most control, in a relationship” “I love walking in the rain, 'cause then no-one knows I'm crying.” “Until this moment, I never understood how hard it was to lose something you never had.” “Being hurt by someone you truly care about leaves a hole in you heart that only love can fill.” “The love that lasts the longest is the love that is never returned.” "I dropped a tear in the ocean, and when you find it, that is when I will stop loving you. A few Quotes from Me, Debra A man should always, say what he means, and mean what he says, because, this is his signature. The more people you have in your life, the more problems, there will be to endure. Smart is a woman who guards her heart. Foolish is a woman, who lets a man, tare her heart apart. © Debra

Semblanza Por Graciela González Phillips Enrique González Rojo Arthur nació en México, D.F., el 5 de octubre de 1928 en un ambiente rodeado de libros. Como él mismo cuenta, poco después de haber nacido sobrevino un temblor y se cayeron dos tomos de la Enciclopedia Británica en su cuna y por poco fue víctima de un "Enciclopediazo". Pero esta no fue la única razón por la cual ha dedicado gran parte de su vida a la lectura y escritura de libros. El ambiente le fue propicio. La educación del abuelo y del padre -sobre todo del primero- sembraron en Enrique una afición y un gran placer por la cultura. Desde muy jóven, cuando su abuelo le preguntaba por un libro, sabía en dónde encontrarlo en la biblioteca. Se había convetido en el librero de la casa. Más tarde expresaría claramente cómo esta devoción determinaría su entorno: ha vivido en bibliotecas que tienen casa, no en casas que tienen biblioteca. Desde la muerte del abuelo y en plena juventud, se afanó en el magisterio. En 1959 obtuvo el grado de maestro en filosofía con una tesis llamada: "Anarquismo y materialismo histórico":, cuyos planteamientos el autor ha modificado y superado. Enrique también realizó los estudios del doctorado en filosofía. Ha residido siempre en el Distrito Federal, a excepción de dos años que vivió junto con su familia en Morelia, Michoacán, donde fue invitado a colaborar como profesor de tiempo completo en la Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Además del magisterio, Enrique se ha dedicado preferentemente a la literatura, a la filosofía y a la militancia política. Después de haber superado hace dos años una grave enfermedad, se encuentra en una de las épocas más prolíficas de su vida, sumando a su afán de escribir sus antiguos gustos por la múscia y el cine, pero ahora con mayor tiempo y disposición. Dijimos con anterioridad que los cuatro pilares de Enrique González Rojo son el magisterio, la literatura, la filosofía y el compromiso político, y nos parece importante señalar que estas partes se interfluyen a lo largo de sus obras. Es evidente que la claridad con que expresa sus ideas se debe a su larga práctica magisterial, que su poesía enarbola motivos filosóficos y políticos sin perder su estructura poética; también que sus escritos filosóficos toman como tema la poesía o la política y sus ensayos políticos se apoyan en concepciones filosóficas y están pertrechados de su estilo literario. De estas pasiones se hablará a continuación. Referencias http://www.enriquegonzalezrojo.com/semblanza.php

Julio Flórez Rea (Chiquinquirá, Boyacá, 22 de mayo de 1867 - Usiacurí, Atlántico, 7 de febrero de 1923) fue un poeta colombiano. Primeros años A los 7 años escribió sus primeros versos conocidos. En 1881 ingresó a estudiar Literatura al Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario en Bogotá, pero no culminó sus estudios debido a la guerra civil de 1885. Su padre fue político liberal, Gobernador del Departamento de Boyacá y Representante a la Cámara. Su hermano Leónidas fue herido gravemente en una manifestación y falleció 4 años después por las secuelas. Julio mismo era un liberal convencido y a pesar de su difícil situación económica rechazó varias veces posiciones ofrecidas por el gobierno conservador, como un cargo en la Biblioteca Nacional o un consulado en el exterior. Amigo de otros dos grandes poetas de la época: Candelario Obeso y José Asunción Silva. Candelario era repudiado por la aristocracia por ser de raza negra y por rechazar los reglamentos impuestos por la iglesia Católica y la sociedad bogotana. En 1884 se suicidó y en su sepelio, Julio Flórez, de sólo 17 años, exaltó su memoria en versos emocionados. Es uno de los más grandes poetas de Colombia, además de ser considerado en su tiempo y por varias décadas después como el poeta popular por excelencia del país. Del exilio al triunfo En 1905, el dictador Rafael Reyes «le aconsejó» irse del país, ante «la ola de murmullos contra él», que lo señalaban como «sacrílego, blasfemo y apóstata». Flórez marchó a Caracas (Venezuela), donde publicó Cardos y lirios y La Araña. Luego viajó por varios países de Centroamérica hasta México. En El Salvador publicó Manojo de zarzas y Cesta de lotos. El exilio fue el trampolín del éxito, la fama de Flórez se hizo internacional y ocurrió lo inesperado: en 1907 su enemigo, el presidente Reyes, lo nombró segundo secretario de la Legación de Colombia en España y Flórez aceptó. Publicó Fronda Lírica, en Madrid en 1908, y Gotas de Ajenjo, en Barcelona en 1909, año en que regresó a Colombia, presentando un recital en Barranquilla. Últimos años A su regreso en 1909 a Colombia, Flórez se retiró al municipio de Usiacurí, en el departamento del Atlántico, a tomar una cura de sus aguas medicinales. En ese pueblo se enamoró de una colegiala de 14 años de edad, Petrona, con quien comenzó un idilio, quedándose a vivir en este sitio por el resto de su vida, salvo algunas salidas esporádicas para realizar funciones o por enfermedad. En 1910 regresó a Bogotá, donde se presentó en una función en el Teatro Colón, durante las celebraciones del primer centenario de la Independencia de Colombia. Luego de esta presentación, Flórez se ausentó de la capital, a la que regresó en muy contadas ocasiones para ofrecer recitales poéticos, del mismo modo como lo hizo en todo el país, y más frecuentemente en la vecina ciudad de Barranquilla. En la aldea de Usiacurí llevó una vida de hogareña, al lado de su esposa Petrona y sus cinco hijos: Cielo, León Julio, Divina, Lira y Hugo Flórez Moreno. Para el mantenimiento de la familia, se dedicó a labores agrícolas y ganaderas a pequeña escala. En esa época le inicio una enfermedad de la cual no se tiene certeza, pero se cree que se trato de un cáncer que le deformo el rostro afectándole la mandíbula izquierda y dificultándole el habla. Falleció el 7 de febrero de 1923 en este poblado a la edad de 55 años. Obra La obra de Julio Flórez consta de diez libros: * Horas * Cardos y lírios * Gotas de ajenjo * Cesta de lotos * Manojo de Zarzas * Haz de espinas * Flecha roja * De pie los muertos * Fronda lírica * Oro y ébano Las poesías más destacadas Mis flores negras, La araña, Idilio eterno, Abstracciones, Resurecciones, La voz del río, Reto, Altas ternuras y Oh poetas, entre otras, son consideradas clásicos de la literatura colombiana. La Gruta Simbólica La Gruta Simbólica fue una tertulia "de errátil asiento", de la que Julio Flórez fue un importante y activo miembro, además de ser uno de sus fundadores. Allí iba, entre rasgueos de tiple, bandola y guitarra, en busca de los manjares criollos y de dorados y diamantinos licores, la bohemia santafereña de mil novecientos. La Gruta Simbólica convocó a lo largo de un quinquenio -sobre poco más o menos- a unas setenta personalidades de la más heterogénea condición. Luis María Mora, llamado "Moratín", narró los acontecimientos que dieron lugar a la fundación de esta tertulia: «... Una noche, cuya fecha nadie podría recordar con precisión, andábamos sin salvoconducto unos cuatro amigos que veníamos de una exquisita cuchipanda, a las cuales eran muy aficionados los literatos de entonces, con pocas excepciones. Era arte muy divertido, peligroso y nuevo ese de sacarle el cuerpo a las patrullas de soldados que rondaban las calles en persecución de sediciosos y espías, cuando de súbito caímos en poder de una ronda. Componían el grupo Carlos Tamayo, Julio Flórez, Julio de Francisco, Ignasio Posse Amaya, Miguel A. Peñarredonda, Rudesindo Gómez y el humilde autor de esta croniquilla, a los pies de vuestras mercedes. No podíamos andar la noche por desafectos al gobierno, y no nos quedaba más remedio que pasarla en un cuartel, cuando menos. De pronto Carlos Tamayo les dijo a los de la ronda: "Señores, tenemos un enfermo grave; vamos en busca de un médico; acompáñenos hasta la casa a llamarlo. Aquí no más es." El oficial consintió en ello. Golpeamos a la ventana de la casa de Rafael Espinosa Guzmán, y apenas asomó éste, Tamayo le dijo: "Doctor ábranos que tenemos un enfermo grave como usted lo ve (y señaló con disimulo a los soldados). Es preciso que vaya a la casa." "Lo haré enseguida (contestó con gravedad el doctor); pero sigan entre tanto." Así lo hicimos y nos quedamos hasta las del alba. Estaban de visita allí aquella noche don Luis Galán y don Pedro Ignasio Escobar. Había necesidad de emplear lo mejor que se pudiese las horas que quedaban hasta el amanecer, y preparamos una alegre tenida. A favor del delicioso vino con que nos regaló el dueño de la casa, recitamos versos, improvisamos un satírico sainete político, cantamos y reímos y olvidamos nuestra pasada cuita con la ronda. Resolvió entonces Reg que hiciéramos nuevas y frecuentes reuniones en su casa, y así, ni una coma más ni una menos, fue como quedó desde esa noche fundada la Gruta Simbólica.» Moratín narró también las nocturnas expediciones que el grupo de la Gruta Simbólica, presidido por Julio Flórez, hacía al Cementerio Central de Bogotá: «Un grupo de soñadores, músicos y poetas, al frente del cual iba él (Julio Flórez), se dirigía al camposanto a eso de la media noche, en las más espléndidas ascensiones de la luna. El grupo salvaba la verja, tomaba el vial del Torreón de Padilla y penetraba en los osarios. Una melancólica música de instrumentos de cuerda sonaba en la cripta. Algunas aves sacudían las alas en los cipreses; cruzaban de lejos las luciérnagas de los fuegos fatuos y la luna iluminaba los mármoles de las tumbas. ¡Eran confidencias con los sepulcros! ¡Eran singulares serenatas a los muertos! Algunos inclinaban la frente contra los troncos de los árboles, y meditaban. Algunas veces Julio Flórez recitaba sus versos a Silva. Luego el grupo tornaba a la ciudad antes que los sorprendiese la claridad del día, y así terminaban las extravagantes visitas a tantos seres idos, ya libres de las cadenas de la carne.» Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julio_Flórez

Buenos días queridos lectores. He de confesaros algo. Me he equivocado demasiadas veces en la vida. Fracasé en mis estudios, en mis propósitos, en mis amoríos, y hasta en mis más férreos sueños, y, aún así, insisto en seguir escribiendo. Es de las pocas cosas que realmente amo, y, creo que, aunque solo me leyese una persona, merecería la pena. Gracias a todos los que me leéis por darme una oportunidad, quizá descifréis más de mí a través de mis escritos. Tenéis también acceso a mi instagram en @tomypoesia _______________________________________ Enero de 2024: He estado realmente liado entre los relatos y el poemario que he estado tratando de publicar, parece que el segundo poemario que había escrito no está siendo muy aceptado (quizá experimenté un poco de más). Aún así hay algunos poemas que me daría pena que no se leyesen y es posible que los suba a redes. Seguiremos informando de las novedades.

Pierre de Ronsard né en septembre 1524 au château, de la Possonnière, près du village de Couture-sur-Loir en Vendômois, et mort le 27 décembre 1585 au prieuré de Saint-Cosme en Touraine), est un des poètes français les plus importants du XVIe siècle. « Prince des poètes et poète des princes », Pierre de Ronsard est une figure majeure de la littérature poétique de la Renaissance. Auteur d’une œuvre vaste qui, en plus de trente ans, s’est portée aussi bien sur la poésie engagée et officielle dans le contexte des guerres de religions avec Les Hymnes et les Discours (1555-1564), que sur l’épopée avec La Franciade (1572) ou la poésie lyrique avec les recueils Les Odes (1550-1552) et des Amours (Les Amours de Cassandre, 1552 ; Les Amours de Marie, 1555 ; Sonnets pour Hélène, 1578).

I have been writing poetry since 2011 and I love doing it because I can express myself. I was bored one day and pick up a pen and paper and started putting words together on paper and now I am passionate about it. I write songs and short stories also but I am more better at writing poetry. I love music very much and I love fashion.

Elvio Romero (1926-2004), Nacido en Yegros, Paraguay, en 1926, se sitúa entre una (la del ‘40) y otra generación (la del ‘50), en la historia de la poesía paraguaya del presente siglo. Infancia y juventud Muy joven, se integró a la promoción de Hérib Campos Cervera, Josefina Plá, Augusto Roa Bastos, que habría de renovar la literatura paraguaya. Fue el más importante, combativo, brillante y talentoso poeta paraguayo del Siglo XX. El crítico y estudioso brasileño Walter Wey escribe, ya en 1951: “El astro del joven poeta es varonil, fuerte e incisivo. Y el estilo, a pesar de ser a veces tosco, duro, de poca vibración, le sirve maravillosamente para los temas de visiones trágicas, de muerte violenta y de hambre y de horizontes desolados... Estamos seguros de que su mensaje, una vez madurado en la experiencia, podrá revelarnos algo sorprendente”. Su trayectoria Militante comunista, luego de la guerra civil de 1947 se ve forzado, con escasos 21 años, y como tantos otros, a abandonar a la que él mismo llama “nuestra profunda tierra”. Desde entonces y hasta su fallecimiento, no volvió a residir en el Paraguay. Viajó incansablemente alrededor del mundo. Jamás olvidó a su patria y a los suyos y las inflexiones de su voz, al decir como pocos poetas su propia poesía, tienen un timbre inconfundiblemente paraguayo. Desempeñó tareas editoriales, pronunciado recitales y conferencias en varios centros culturales de América y Europa. El gran novelista guatemalteco Miguel Ángel Asturias, premio Nobel de literatura en 1967, en la presentación del libro de Romero “El sol bajo las raíces” (1956), brinda un maravilloso recado acerca del poeta y su obra: “Lo que caracteriza la poesía de Elvio Romero es su sabor a tierra, a madera, a agua, a sol, el rigor con que trata sus temas, no abandonándose ni un solo momento a la facilidad del verso, y el querer interpretar el drama de su país joyoso de naturaleza y triste de existencia, como muchos de nuestros países. Pocas voces americanas tan hondas y fieles al hombre y sus problemas, y por eso universal. Poesía invadida, llamo yo a esta poesía. Poesía invadida por la vida, por el juego y el fuego de la vida. Pero no la vida como la concibe el europeo, chato siempre ante nuestro mundo maravilloso y mágico, sino como la concebimos nosotros. Elvio Romero, como todos los auténticos poetas de América, no tiene que poblar un mundo vacío con su imaginación. Ese mundo ya existe. Interpretarlo es su papel, lo real es lo poético en América, no lo imaginado o ficticio. Y por eso se nos queda tanta geografía dispersa en flores, en astros, en piedras, en aves, cuando leemos los poemas de este inspirado poeta paraguayo. Por los intersticios de tanto prodigio como va cantando, se escapa el dolor de los pueblos, gemido y protesta, pero también esperanza y fe. Pero estos sentimientos y pensamientos nacidos del paisaje que se torna lúcido y que por momentos llegan a ser opresores, son rotos por el poeta que los “nombra”. Romper el encantamiento “nombrándolos” es el arte de Elvio Romero, el encantamiento natural, ya que son transpuestos a sus poemas en el logro de otro encanto, el de la poesía, el sobrenatural. Sobre la naturaleza van sus versos arrastrando raíces de sangre viva, de vértigo, contraste y metamorfosis. Lo formal, se cuenta, cuenta poco en poetas en que hay una tempestad atronadora, en los cuales lo que se dice se expande y al expandirse crea o recrea, del mundo nuevo, su vibración auténtica.” Y Rafael Alberti, notable exponente de la generación poética del 27 en la literatura española le canta, en los encendidos versos de su poema “Elvio Romero, poeta paraguayo”: “Las alas, sí, las alas, contra la vida quieta Cante, llore el poeta volando entre las balas. Por los signos del día también tú señalado clavel arrebatado y espada de agonía Casi recién nacida, lumbre madura y fuerte, sabes más de la muerte quizás que de la vida. Y tu nombre aromado huele más que a romero, a pólvora, a reguero de cuerpo ensangrentado. La patria encadenada y herida se sostiene sin sueño y te mantiene el alma desterrada. Y mientras que penando sin luz va el enemigo, la Libertad contigo regresará cantando”. Gabriela Mistral, la premio Nobel chilena, por su parte, escribe: “Pocas veces he sentido la tierra como acostada sobre un libro”. "Elvio Romero, la fuerza de la realidad" es el ensayo del escritor y poeta argentino Ricardo Rubio, publicado en Asunción en 2003. "Elvio Romero - De la tierra intensa", ensayo del mismo autor, se publicó en Buenos Aires en 2006. [editar]Su vida en el exilio Exilio, desamparo, amor, esas otras expresiones de la misma vida, están permanentemente presentes en la prolífica obra de Romero. El mismo poeta nos dice: “Durante el largo exilio que padecí, mis compatriotas, mis amigos, y algunos desconocidos también, se acercaron a mi casa de exiliado, trayendo la fragancia de las cosas lejanas, reconfortando mi retiro. Compartí la lucha de mi pueblo por su libertad, viví atento a la formidable gesta protagonizada por los miles de combatientes que, cautelosa y valerosamente, prepararon el porvenir de la patria, y mi canto se fue conformando así, entre exaltaciones vibrantes y melancolías, de esas luces y sombras que, alternativamente, estremecen el alma. No se ya si pronto, o tarde, comprendí que debía recoger en mi poesía todos los estados de ánimo que brotaron de esas tristezas fugaces y de una impresionante e impertinente rebeldía. Entonces abrí todas mis ventanas para que entrasen los vientos del mundo, y así pude juntar las desvaídas hojas del decaimiento con la ardiente ramazón de un fuego combativo. Todos mis sentimientos, todos, se mezclaron, como en la galera de un prestidigitador los papelitos de colores y desde donde salió volando una paloma de oro al calor de mis pasiones y mis imaginerías”. Obras Poéticas Año Obra * 1948 Días roturados * 1950 Resoles áridos * 1953 Despiertan las fogatas * 1956 El sol bajo las raíces * 1961 De cara al corazón * 1961 Esta guitarra dura * 1966 Libro de la migración * 1967 Un relámpago herido * 1970 Los innombrables * 1975 Destierro y atardecer * 1977 El viejo fuego * 1984 Los valles imaginarios * 1994 Flechas en un arco tendido * 2007 Cantar de caminante Distinciones * Como ensayista es autor de “Miguel Hernández, destino y poesía” (1958) y de “El poeta y sus encrucijadas” (1991), obra con la cual se hizo acreedor del Premio Nacional de Literatura en su primera edición. * Fue colaborador del diario Última Hora, de Asunción, y de numerosas publicaciones culturales en la Argentina. * Residiendo en Buenos Aires, Argentina, donde desempeñaba funciones diplomáticas en el carácter de Agregado Cultural de la Embajada Paraguaya en la capital porteña, falleció el 19 de mayo de 2004. Wikipwedia- Referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elvio_Romero

Alicia Ros El 17 -12-2011 Publique mi primer libro como autora -editora “Arco Iris de mi Sueños” Literatura infantil .Escribo para niños y adultos. Soltare mi escritura al vuelo, para que crezca Difundiré la lectura para que enriquezca Agradeceré al lector el cual me lea Aunque no le guste, o gustoso sea Desde mi corazón muchas gracias Alicia Ros ( Argentina )