Info

A Limier Briquet Hound

Rosa Bonheur

1856

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

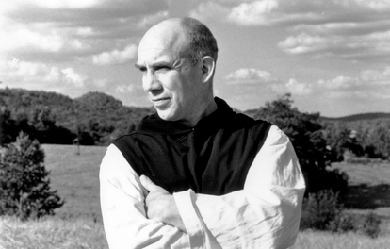

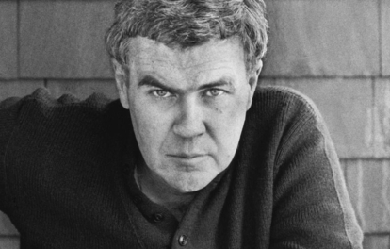

Thomas Merton (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist, and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the priesthood and given the name Father Louis.Merton wrote more than 70 books, mostly on spirituality, social justice and a quiet pacifism, as well as scores of essays and reviews. Among Merton’s most enduring works is his bestselling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain (1948), which sent scores of World War II veterans, students, and even teenagers flocking to monasteries across the US, and was also featured in National Review’s list of the 100 best non-fiction books of the century. Merton was a keen proponent of interfaith understanding. He pioneered dialogue with prominent Asian spiritual figures, including the Dalai Lama, the Japanese writer D. T. Suzuki, the Thai Buddhist monk Buddhadasa, and the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, and authored books on Zen Buddhism and Taoism. In the years since his death, Merton has been the subject of several biographies.

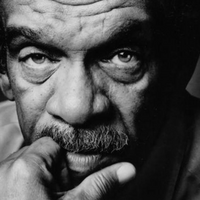

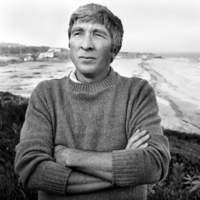

Sir Derek Alton Walcott, KCSL OBE OCC (born 23 January 1930) is a Saint Lucian–Trinidadian poet and playwright. He received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. He is currently Professor of Poetry at the University of Essex. His works include the Homeric epic poem Omeros (1990), which many critics view “as Walcott’s major achievement.” In addition to having won the Nobel, Walcott has won many literary awards over the course of his career, including an Obie Award in 1971 for his play Dream on Monkey Mountain, a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award, a Royal Society of Literature Award, the Queen’s Medal for Poetry, the inaugural OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, the 2011 T. S. Eliot Prize for his book of poetry White Egrets and the Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award in 2015. Early life and education Walcott was born and raised in Castries, Saint Lucia, in the West Indies with a twin brother, the future playwright Roderick Walcott, and a sister, Pamela Walcott. His family is of African and European descent, reflecting the complex colonial history of the island which he explores in his poetry. His mother, a teacher, loved the arts and often recited poetry around the house. His father, who painted and wrote poetry, died at age 31 from mastoiditis while his wife was pregnant with the twins Derek and Roderick, who were born after his death. Walcott’s family was part of a minority Methodist community, who felt overshadowed by the dominant Catholic culture of the island established during French colonial rule. As a young man Walcott trained as a painter, mentored by Harold Simmons, whose life as a professional artist provided an inspiring example for him. Walcott greatly admired Cézanne and Giorgione and sought to learn from them. Walcott’s painting was later exhibited at the Anita Shapolsky Gallery in New York City, along with the art of other writers, in a 2007 exhibition named “The Writer’s Brush: Paintings and Drawing by Writers”. He studied as a writer, becoming “an elated, exuberant poet madly in love with English” and strongly influenced by modernist poets such as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. Walcott had an early sense of a vocation as a writer. In the poem “Midsummer” (1984), he wrote: At 14, Walcott published his first poem, a Miltonic, religious poem in the newspaper, The Voice of St Lucia. An English Catholic priest condemned the Methodist-inspired poem as blasphemous in a response printed in the newspaper. By 19, Walcott had self-published his two first collections with the aid of his mother, who paid for the printing: 25 Poems (1948) and Epitaph for the Young: XII Cantos (1949). He sold copies to his friends and covered the costs. He later commented, I went to my mother and said, 'I’d like to publish a book of poems, and I think it’s going to cost me two hundred dollars.' She was just a seamstress and a schoolteacher, and I remember her being very upset because she wanted to do it. Somehow she got it—a lot of money for a woman to have found on her salary. She gave it to me, and I sent off to Trinidad and had the book printed. When the books came back I would sell them to friends. I made the money back. The influential Bajan poet Frank Collymore critically supported Walcott’s early work. With a scholarship, he studied at the University College of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica. Personal life Derek Walcott married Fay Moston, a secretary, but the marriage lasted only a few years and ended in divorce. Walcott married a second time to Margaret Maillard, who worked as an almoner in a hospital, but that also ended in divorce. In 1976, Walcott then married Norline Metivier, but this marriage also did not last. He has children named Elizabeth, Peter and Anna. Walcott is also known for his passion for traveling to different countries around the world. He splits his time between New York, Boston, and St. Lucia, where he incorporates the influences of different areas into his pieces of work. Career After graduation, Walcott moved to Trinidad in 1953, where he became a critic, teacher and journalist. Walcott founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop in 1959 and remains active with its Board of Directors. Exploring the Caribbean and its history in a colonialist and post-colonialist context, his collection In a Green Night: Poems 1948–1960 (1962) attracted international attention. His play Dream on Monkey Mountain (1970) was produced on NBC-TV in the United States the year it was published. In 1971 it was produced by the Negro Ensemble Company off-Broadway in New York City; it won an Obie Award that year for “Best Foreign Play”. The following year, Walcott won an OBE from the British government for his work. He was hired as a teacher by Boston University in the United States, where he founded the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre in 1981. That year he also received a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in the United States. Walcott taught literature and writing at Boston University for more than two decades, publishing new books of poetry and plays on a regular basis and retiring in 2007. He became friends with other poets, including the Russian Joseph Brodsky, who lived and worked in the US after being exiled in the 1970s, and the Irish Seamus Heaney, who also taught in Boston. His epic poem, Omeros (1990), which loosely echoes and refers to characters from The Iliad, has been critically praised “as Walcott’s major achievement.” The book received praise from publications such as The Washington Post and The New York Times Book Review, which chose the book as one of its "Best Books of 1990". Walcott was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992, the second Caribbean writer to receive the honor after Saint-John Perse, who was born in Guadeloupe, received the award in 1960. The Nobel committee described Walcott’s work as “a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment.” He won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2004. His later poetry collections include Tiepolo’s Hound (2000), illustrated with copies of his watercolors; The Prodigal (2004), and White Egrets (2010), which received the T.S. Eliot Prize. In 2009, Walcott began a three-year distinguished scholar-in-residence position at the University of Alberta. In 2010, he became Professor of Poetry at the University of Essex. As a part of St Lucia’s Independence Day celebrations, in February 2016, he became one of the first knights of the Order of Saint Lucia, granting him the title of 'Sir’. Oxford Professor of Poetry candidacy In 2009, Walcott was a leading candidate for the position of Oxford Professor of Poetry. He withdrew his candidacy after reports of documented accusations against him of sexual harassment from 1981 and 1996. (The latter case was settled by Boston University out of court.) When the media learned that pages from an American book on the topic were sent anonymously to a number of Oxford academics, this aroused their interest in the university decisions. Ruth Padel, also a leading candidate, was elected to the post. Within days, The Daily Telegraph reported that she had alerted journalists to the harassment cases. Under severe media and academic pressure, Padel resigned. Padel was the first woman to be elected to the Oxford post, and journalists including Libby Purves, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, the American Macy Halford and the Canadian Suzanne Gardner attributed the criticism of her to misogyny and a gender war at Oxford. They said that a male poet would not have been so criticized, as she had reported published information, not rumour. Numerous respected poets, including Seamus Heaney and Al Alvarez, published a letter of support for Walcott in The Times Literary Supplement, and criticized the press furore. Other commentators suggested that both poets were casualties of the media interest in an internal university affair, because the story “had everything, from sex claims to allegations of character assassination”. Simon Armitage and other poets expressed regret at Padel’s resignation. Writing Themes Methodism and spirituality have played a significant role from the beginning in Walcott’s work. He commented, “I have never separated the writing of poetry from prayer. I have grown up believing it is a vocation, a religious vocation.” Describing his writing process, he wrote, "the body feels it is melting into what it has seen… the 'I’ not being important. That is the ecstasy... Ultimately, it’s what Yeats says: ‘Such a sweetness flows into the breast that we laugh at everything and everything we look upon is blessed.’ That’s always there. It’s a benediction, a transference. It’s gratitude, really. The more of that a poet keeps, the more genuine his nature." He also notes, “if one thinks a poem is coming on... you do make a retreat, a withdrawal into some kind of silence that cuts out everything around you. What you’re taking on is really not a renewal of your identity but actually a renewal of your anonymity.” Influences Walcott has said his writing was influenced by the work of the American poets, Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop, who were also friends. Playwriting He has published more than twenty plays, the majority of which have been produced by the Trinidad Theatre Workshop and have also been widely staged elsewhere. Many of them address, either directly or indirectly, the liminal status of the West Indies in the post-colonial period. Through poetry he also explores the paradoxes and complexities of this legacy. Essays In his 1970 essay “What the Twilight Says: An Overture”, discussing art and theatre in his native region (from Dream on Monkey Mountain and Other Plays), Walcott reflects on the West Indies as colonized space. He discusses the problems for an artist of a region with little in the way of truly indigenous forms, and with little national or nationalist identity. He states: “We are all strangers here... Our bodies think in one language and move in another". The epistemological effects of colonization inform plays such as Ti-Jean and his Brothers. Mi-Jean, one of the eponymous brothers, is shown to have much information, but to truly know nothing. Every line Mi-Jean recites is rote knowledge gained from the coloniser; he is unable to synthesize it or apply it to his life as a colonised person. Walcott notes of growing up in West Indian culture: “What we were deprived of was also our privilege. There was a great joy in making a world that so far, up to then, had been undefined... My generation of West Indian writers has felt such a powerful elation at having the privilege of writing about places and people for the first time and, simultaneously, having behind them the tradition of knowing how well it can be done—by a Defoe, a Dickens, a Richardson.” Walcott identifies as “absolutely a Caribbean writer”, a pioneer, helping to make sense of the legacy of deep colonial damage. In such poems as “The Castaway” (1965) and in the play Pantomime (1978), he uses the metaphors of shipwreck and Crusoe to describe the culture and what is required of artists after colonialism and slavery: both the freedom and the challenge to begin again, salvage the best of other cultures and make something new. These images recur in later work as well. He writes, “If we continue to sulk and say, Look at what the slave-owner did, and so forth, we will never mature. While we sit moping or writing morose poems and novels that glorify a non-existent past, then time passes us by.” Omeros Walcott’s epic book-length poem Omeros was published in 1990 to critical acclaim. The poem very loosely echoes and references Homer and some of his major characters from The Iliad. Some of the poem’s major characters include the island fishermen Achille and Hector, the retired English officer Major Plunkett and his wife Maud, the housemaid Helen, the blind man Seven Seas (who symbolically represents Homer), and the author himself. Although the main narrative of the poem takes place on the island of St. Lucia, where Walcott was born and raised, Walcott also includes scenes from Brookline, Massachusetts (where Walcott was living and teaching at the time of the poem’s composition), and the character Achille imagines a voyage from Africa onto a slave ship that is headed for the Americas; also, in Book Five of the poem, Walcott narrates some of his travel experiences in a variety of cities around the world, including Lisbon, London, Dublin, Rome, and Toronto. Composed in a variation on terza rima, the work explores the themes that run throughout Walcott’s oeuvre: the beauty of the islands, the colonial burden, the fragmentation of Caribbean identity, and the role of the poet in a post-colonial world. Criticism and praise Walcott’s work has received praise from major poets including Robert Graves, who wrote that Walcott “handles English with a closer understanding of its inner magic than most, if not any, of his contemporaries”, and Joseph Brodsky, who praised Walcott’s work, writing: “For almost forty years his throbbing and relentless lines kept arriving in the English language like tidal waves, coagulating into an archipelago of poems without which the map of modern literature would effectively match wallpaper. He gives us more than himself or 'a world’; he gives us a sense of infinity embodied in the language.” Walcott noted that he, Brodsky, and the Irish poet Seamus Heaney, who all taught in the United States, were a band of poets “outside the American experience”. The poetry critic William Logan critiqued Walcott’s work in a New York Times book review of Walcott’s Selected Poems. While he praised Walcott’s writing in Sea Grapes and The Arkansas Testament, he had mostly negative things to say about Walcott’s poetry, calling Omeros “clumsy” and Another Life “pretentious.”. Finally, he concluded with the faint praise that “No living poet has written verse more delicately rendered or distinguished than Walcott, though few individual poems seem destined to be remembered.” Most reviews of Walcott’s work are more positive. For instance, in The New Yorker review of The Poetry of Derek Walcott, Adam Kirsch had high praise for Walcott’s oeuvre, describing his style in the following manner: By combining the grammar of vision with the freedom of metaphor, Walcott produces a beautiful style that is also a philosophical style. People perceive the world on dual channels, Walcott’s verse suggests, through the senses and through the mind, and each is constantly seeping into the other. The result is a state of perpetual magical thinking, a kind of Alice in Wonderland world where concepts have bodies and landscapes are always liable to get up and start talking. He calls Another Life Walcott’s “first major peak” and analyzes the painterly qualities of Walcott’s imagery from his earliest work through to later books like Tiepolo’s Hound. He also explores the post-colonial politics in Walcott’s work, calling him “the postcolonial writer par excellence.” He calls the early poem “A Far Cry from Africa” a turning point in Walcott’s development as a poet. Like Logan, Kirsch is critical of Omeros which he believes Walcott fails to successfully sustain over its entirety. Although Omeros is the volume of Walcott’s that usual receives the most critical praise, Kirsch, instead believes that Midsummer is his best book. Awards and honours 1969 Cholmondeley Award 1971 Obie Award for Best Foreign Play (for Dream on Monkey Mountain) 1972 Officer of the Order of the British Empire 1981 MacArthur Foundation Fellowship ("genius award") 1988 Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry 1990 Arts Council of Wales International Writers Prize 1990 W. H. Smith Literary Award (for poetry Omeros) 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature 2004 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement 2008 Honorary doctorate from the University of Essex 2011 T. S. Eliot Prize (for poetry collection White Egrets) 2011 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature (for White Egrets) 2015 Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award 2016 Knight Commander of the Order of Saint Lucia List of works * Works about Derek Walcott in libraries (WorldCat catalog) * Works by Derek Walcott at Open Library Further reading * Baer, William, ed. Conversations with Derek Walcott. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996. * Baugh, Edward, Derek Walcott: Memory as Vision: Another Life. London: Longman, 1978. * Baugh, Edward, Derek Walcott. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. * Breslin, Paul, Nobody’s Nation: Reading Derek Walcott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. ISBN 0-226-07426-9 * Brown, Stewart, ed., The Art of Derek Walcott. Chester Springs, PA.: Dufour, 1991; Bridgend: Seren Books, 1992. * Burnett, Paula, Derek Walcott: Politics and Poetics. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, The Flight of the Vernacular: Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott and the Impress of Dante. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, 2001. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, Agenda 39:1–3 (2002–03), Special Issue on Derek Walcott. Includes Derek Walcott’s Epitaph for the Young (1949) republished here in its entirety. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina and Patrick, Peter, “Two Healing Narratives: Suffering, Reintegration, and the Struggle of Language”, Small Axe 20 10:2 (2006), pp. 61–79. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, “Brushing History Against the Grain: Derek Walcott’s Tiepolo’s Hound”, in Caribbean Perspectives on Modernity: Returning Medusa’s Gaze. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009. * Gazzoni, Andrea, Epica dell’arcipelago. Il racconto della tribù, Derek Walcott, “Omeros”. Firenze: Le Lettere, 2009. ISBN 88-6087-288-X * Hamner, Robert D., ed. Critical Perspectives on Derek Walcott. Washington, D.C.: Three Continents, 1993. ISBN 0-89410-142-0 * Hamner, Robert D., Derek Walcott. Updated Edition. Twayne’s World Authors Series. TWAS 600. New York: Twayne, 1993. * Heaney, Seamus, “The Murmur of Malvern”, in The Government of the Tongue: The 1986 T. S. Eliot Memorial Lectures and Other Critical Writings. London: Faber and Faber, 1988, pp. 23–29. * King, Bruce, Derek Walcott and West Indian Drama: “Not Only a Playwright But a Company”: The Trinidad Theatre Workshop 1959–1993. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. * King, Bruce, Derek Walcott, A Caribbean Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. * Lennard, John, “Derek Walcott”, in Jay Parini, ed., World Writers in English. 2 vols, New York & London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004, II.721–46. * Morris, Mervyn, “Derek Walcott”, in Bruce King, ed., West Indian Literature, Macmillan, 1979, pp. 144–60. * Parker, Michael and Roger Starkey, eds. New Casebooks: Postcolonial Literatures: Achebe, Ngugi, Desai, Walcott. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, 1995. ISBN 0-333-60801-1 * Sinnewe, Dirk, Divided to the Vein? Derek Walcott’s Drama and the Formation of Cultural Identities. Saarbrücken: Königshausen und Neumann, 2001 [Reihe Saarbrücker Beiträge 17]. ISBN 3-8260-2073-1 * Terada, Rei, Derek Walcott’s Poetry: American Mimicry. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992. * Thieme, John, Derek Walcott. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1999. * Walcott, Derek, Dream on Monkey Mountain and Other Plays. New York: Farrar, 1970. ISBN 0-374-50860-7 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derek_Walcott

Edward George Dyson (4 March 1865– 22 August 1931) was an Australian journalist, poet, playwright and short story writer. He was the elder brother of talented illustrators Will Dyson and Ambrose Dyson. At 19, he began writing verse and, a few years later, embarked on a life of freelance journalism which lasted until his death. In 1896 he published a volume of poems, Rhymes from the Mines and, in 1898, the first collection of his short stories, Below and On Top.

Ernest Christopher Dowson (2 August 1867– 23 February 1900) was an English poet, novelist, and short-story writer, often associated with the Decadent movement. He was born in Lee, London, in 1867. His great-uncle was Alfred Domett, a poet and politician who became Premier of New Zealand and had allegedly been the subject of Robert Browning’s poem “Waring.” Dowson attended The Queen’s College, Oxford, but left in March 1888 before obtaining a degree.

William Henry Davies or W. H. Davies (3 July 1871 – 26 September 1940) was a Welsh poet and writer. Davies spent a significant part of his life as a tramp or hobo, in the United Kingdom and United States, but became one of the most popular poets of his time. The principal themes in his work are observations about life's hardships, the ways in which the human condition is reflected in nature, his own tramping adventures and the various characters he met. Davies is usually considered one of the Georgian Poets, but much of his work is not typical in style or theme of the group. Early Life The son of an iron moulder, Davies was born at 6, Portland Street in the Pillgwenlly district of Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales, a busy port. He had an older brother, Francis Gomer Boase (who was considered "slow") and in 1874 his younger sister Matilda was born. In November 1874, when William was aged three, his father died. The following year his mother Mary Anne Davies remarried and became Mrs Joseph Hill. She agreed that care of the three children should pass to their paternal grandparents, Francis and Lydia Davies, who ran the nearby Church House Inn at 14, Portland Street. His grandfather Francis Boase Davies, originally from Cornwall, had been a sea captain. Davies was related to the famous British actor Sir Henry Irving (referred to as cousin Brodribb by the family); he later recalled that his grandmother referred to Irving as " the cousin who brought disgrace on us". Davies' grandmother was described, by a neighbour who remembered her, as wearing ".. pretty little caps, with bebe ribbon, tiny roses and puce trimmings". Writing in his Introduction to the 1943 Collected Poems of W. H. Davies, Osbert Sitwell recalled Davies telling him that, in addition to his grandparents and himself, his home consisted of "an imbecile brother, a sister ... a maidservant, a dog, a cat, a parrot, a dove and a canary bird." Sitwell also recounts that Davies' grandmother, a Baptist by denomination, was "of a more austere and religious turn of mind than her husband." In 1879 the family moved to Raglan Street, then later to Upper Lewis Street, from where William attended Temple School. In 1883 he moved to Alexandra Road School and the following year was arrested, as one of a gang of five schoolmates, and charged with stealing handbags. He was given twelve strokes of the birch. In 1885 Davies wrote his first poem entitled "Death". In his Poet's Pilgrimage (1918) Davies recounts the time when, at the age of 14, he was left with orders to sit with his dying grandfather. He missed the final moments of his grandfather's death as he was too engrossed in reading "a very interesting book of wild adventure". Delinquent to Supertramp Having finished school under the cloud of his theft he worked first for an ironmonger. In November 1886, his grandmother signed the papers for Davies to begin a five-year apprenticeship to a local picture-frame maker. Davies never enjoyed the craft, however, and never settled into any regular work. He was a difficult and somewhat delinquent young man, and made repeated requests to his grandmother to lend him the money to sail to America. When these were all refused, he eventually left Newport, took casual work and started to travel. The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp, published in 1908, covers his life in the USA between 1893 and 1899, including many adventures and characters from his travels as a drifter. During this period he crossed the Atlantic at least seven times, working on cattle ships. He travelled through many of the states, sometimes begging, sometimes taking seasonal work, but often ending up spending any savings on a drinking spree with a fellow traveller. He took advantage of the corrupt system of "boodle", in order to pass the winter in Michigan, by agreeing to be locked up in a series of different jails. Here, with his fellow tramps, Davies would enjoy the relative comfort of "card-playing, singing, smoking, reading, relating experiences and occasionally taking exercise or going out for a walk." At one stage, on his way to Memphis, Tennessee, he lay alone in a swamp for three days and nights suffering from malaria. The turning point in Davies' life came when, after a week of rambling in London, he spotted a newspaper story about the riches to be made in the Klondike and immediately set off to make his fortune in Canada. Attempting to jump a freight train at Renfrew, Ontario, on 20 March 1899, with fellow tramp Three-fingered Jack, he lost his footing and his right foot was crushed under the wheels of the train. The leg later had to be amputated below the knee and he wore a wooden leg thereafter. Davies' biographers have agreed that the significance of the accident should not be underestimated, even though Davies himself played down the story. Moult begins his biography with the incident and Stonesifer has suggested that this event, more than any other, led Davies to become a professional poet. Davies himself wrote of the accident: "I bore this accident with an outward fortitude that was far from the true state of my feelings. Thinking of my present helplessness caused me many a bitter moment, but I managed to impress all comers with a false indifference… I was soon home again, having been away less than four months; but all the wildness had been taken out of me, and my adventures after this were not of my own seeking, but the result of circumstances." Davies' view of his own disability was ambivalent. In his poem "The Fog", published in the 1913 Foliage, a blind man leads the poet through the fog, showing the reader that one who is handicapped in one domain may well have a considerable advantage in another. Poet He returned to Britain, living a rough life, particularly in London shelters and doss-houses, including the Salvation Army hostel in Southwark known as "The Ark" which he grew to despise. Fearing the contempt of his fellow tramps, he would often feign slumber in the corner of his doss-house, mentally composing his poems and only later committing them to paper in private. At one stage he borrowed money to have his poems printed on loose sheets of paper, which he then tried to sell door-to-door through the streets of residential London. When this enterprise failed, he returned to his lodgings and, in a fit of rage, burned all of the printed sheets in the fire. Davies self-published his first book of poetry, The Soul's Destroyer, in 1905, again by means of his own savings. It proved to be the beginning of success and a growing reputation. In order to even get the slim volume published, Davies had to forgo his allowance and live the life of a tramp for six months (with the first draft of the book hidden in his pocket), just to secure a loan of funds from his inheritance. When eventually published, the volume was largely ignored and he resorted to posting individual copies by hand to prospective wealthy customers chosen from the pages of Who's Who, asking them to send the price of the book, a half crown, in return. He eventually managed to sell 60 of the 200 copies printed. One of the copies was sent to Arthur Adcock, then a journalist with the Daily Mail. On reading the book, as he later wrote in his essay "Gods Of Modern Grub Street", Adcock said that he "recognised that there were crudities and even doggerel in it, there was also in it some of the freshest and most magical poetry to be found in modern books". He sent the price of the book and asked Davies to meet him. Adcock is still generally regarded as "the man who discovered Davies". The first trade edition of The Soul's Destroyer was published by Alston Rivers in 1907. A second edition followed in 1908 and a third in 1910. A 1906 edition, by Fifield, was advertised but has not been verified. Rural life in Kent On 12 October 1905 Davies met Edward Thomas, then literary critic for the Daily Chronicle in London, who was to do more to help him than anyone else. Thomas rented for Davies the tiny two-roomed "Stidulph's Cottage", in Egg Pie Lane, not far from his own home at Elses Farm near Sevenoaks in Kent. Davies moved to the cottage, from 6 Llanwern Street, Newport, via London, in the second week of February 1907. The cottage was "only two meadows off" from Thomas' own house. Thomas adopted the role of protective guardian for Davies, on one occasion even arranging for the manufacture, by a local wheelwright, of a makeshift replacement wooden leg, which was invoiced to Davies as "a novelty cricket bat". In 1907, the manuscript of The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp drew the attention of George Bernard Shaw, who agreed to write a preface (largely through the concerted efforts of his wife Charlotte). It was only because of Shaw that Davies' contract with the publishers was rewritten to allow the author to retain the serial rights, all rights after three years, royalties of fifteen per cent of selling price and a non-returnable advance of twenty five pounds. Davies was also to be given a say on the style of all illustrations, advertisement layouts and cover designs. The original publisher, Duckworth and Sons, refused to accept these demands and so the book was placed instead with London publisher Fifield. A number of anecdotes of Davies' time with the Thomas family in Kent are recounted in the brief account later published by Thomas' widow Helen. In 1911, Davies was awarded a Civil List Pension of £50, later increased to £100 and then again to £150. Davies started to spend more time in London and made many literary friends and acquaintances. Though averse to giving autographs himself, Davies began to make a collection of his own and was particularly keen to obtain that of D. H. Lawrence. Georgian poetry publisher Edward Marsh was able to secure an autograph and also invited Lawrence and wife-to-be Frieda to meet Davies on 28 July 1913. Lawrence was immediately captivated by Davies and later invited him to join them in Germany. Despite his early enthusiasm for Davies' work, however, Lawrence's opinion changed after reading Foliage and he commented after reading Nature Poems in Italy that the verses seemed "so thin, one can hardly feel them". By this time Davies had amassed a library of about fifty books in his cottage, mostly of 16th- and 17th-century poets, and including Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Byron, Burns, Shelley, Keats, Coleridge, Blake and Herrick. In December 1908 his essay "How It Feels To Be Out of Work", described by Stonesifer as "a rather pedestrian performance", appeared in the pages of The English Review. He continued to send other periodical articles out to editors, but without any success. Society life in London After lodging at a number of temporary addresses in Sevenoaks, Davies moved back to London early in 1914, settling eventually at 14 Great Russell Street in the Bloomsbury district, previously the residence of Charles Dickens. Here in a tiny two-room apartment, initially infested with mice and rats, and next door to rooms occupied by a noisy Belgian prostitute, he lived from early 1916 until 1921. It was during this time in London that Davies embarked on a series of public readings of his work, alongside such others as Hilaire Belloc and W. B. Yeats, impressing such fellow poets as Ezra Pound. He soon found that he was able to socialise with leading society figures of the day, including Lord Balfour and Lady Randolph Churchill. While in London Davies also became friendly with a number of artists, including Jacob Epstein, Harold and Laura Knight, Nina Hamnett, Augustus John, Harold Gilman, William Rothenstein, Walter Sickert, Sir William Nicholson and Osbert and Edith Sitwell. He enjoyed the society of literary men and their conversation, particularly in the rarefied atmosphere downstairs at the Café Royal. He would also meet regularly with W. H. Hudson, Edward Garrett and others at The Mont Blanc in Soho. In his poetry Davies drew extensively for material on his experiences with the seamier side of life, but also on his love of nature. By the time of his prominent place in the Edward Marsh Georgian Poetry series, he was an established figure. He is generally best known for the opening two lines of the poem "Leisure", first published in Songs Of Joy and Others in 1911: "What is this life if, full of care / We have no time to stand and stare..." In October 1917 his work was included in the anthology Welsh Poets: A Representative English selection from Contemporary Writers collated by A. G. Prys-Jones and published by Erskine Macdonald of London. In the last months of 1921, Davies moved to more comfortable quarters at 13 Avery Row, Brook Street, where he rented rooms from the Quaker poet Olaf Baker. He began to find prolonged work difficult, however, suffering from increased bouts of rheumatism and other ailments. Harlow (1993) lists a total of 14 BBC broadcasts of Davies reading his own work made between 1924 and 1940 (now held in the BBC broadcast archive) although none included his most famous work, "Leisure". Later Days, the 1925 sequel to The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp, describes the beginnings of Davies' career as a writer and his acquaintance with Belloc, Shaw and de la Mare, amongst many others. He became "the most painted literary man of his day", drawn and painted by Augustus John, Sir William Nicholson, Dame Laura Knight and Sir William Rothenstein. His head in bronze was the most successful of Epstein's smaller works. Honours, memorials and legacy In 1926 Davies was honoured with the degree of Doctor Litteris, honoris causa from the University of Wales. Davies returned to his native Newport in 1930, where a luncheon was held in his honour at the Westgate Hotel. His return, in September 1938, for the unveiling of the plaque in his honour, proved to be his last public appearance. A large collection of Davies manuscripts, including a copy of "Leisure", dated 8 May 1914, is held by the National Library of Wales. The collection includes a copy of "A Boy's Sorrow", an apparently unpublished poem of two eight-line stanzas relating to the death of a neighbour. Also included is a volume (c. 1916) containing autograph fair copies of 15 Davies poems, some of them apparently unpublished, submitted to James Guthrie (1874–1952) for publication by the Pear Tree Press as a collection entitled Quiet Streams, to which annotations have been added by Lord Kenyon. British writer Gerald Brenan (1894–1987) and his generation were influenced by Davies' Autobiography of a Super-Tramp. In 1951 Jonathan Cape published The Essential W. H. Davies, selected and with an introduction by Brian Waters, a young Gloucestershire poet and writer whose work Davies admired, who described him as "about the last of England's professional poets". The collection included The Autobiography of a Super-tramp, and extracts from Beggars, A Poet's Pilgrimage, Later Days, My Birds and My Garden, as well as over 100 poems arranged by publication period. Many of Davies' poems have been given a musical setting. "Money, O!" was set to music for piano, in G minor, by Michael Head - his 1929 Boosey & Hawkes collection also included settings for "The Likeness", "The Temper of a Maid", "Natures' Friend", "Robin Redbreast" and "A Great Time". There are also three songs by Sir Arthur Bliss - "Thunderstorms", "This Night", and "Leisure" - as well as "The Rain" for voice and piano, by Margaret Campbell Bruce, published in 1951 by J. Curwen and Sons. Experimental Irish folk group Dr Strangely Strange also sang and quoted from "Leisure" on their 1970 album Heavy Petting, with harmonium accompaniment. A musical adaptation of the same poem, with John Karvelas (vocals) and Nick Pitloglou (piano) and an animated film by Pipaluk Polanksi, may be found on YouTube. Also in 1970, Fleetwood Mac recorded "Dragonfly", a song with lyrics taken from Davies' 1927 poem, "The Dragonfly". The song was also recorded by English singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Blake, for his 2011 album The First Snow. On 1 July 1971 a special First Day Cover, with a matching commemorative post-mark was issued by the UK Post Office to mark Davies' centenary. A controversial statue by Paul Bothwell-Kincaid, inspired by the poem "Leisure", was unveiled in Commercial Street, Newport in December 1990, to commemorate Davies' work, on the 50th anniversary of his death. The bronze head of Davies by Epstein, from January 1917, regarded by many as the most accurate artistic impression of Davies and a copy of which Davies owned himself, may be found at Newport Museum and Art Gallery (donated by Viscount Tredegar). In August 2010 the play Supertramp, Sickert and Jack the Ripper by Lewis Davies, concerning an imagined sitting by Davies for a portrait by Walter Sickert, premiered at the Edinburgh Festival. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._H._Davies

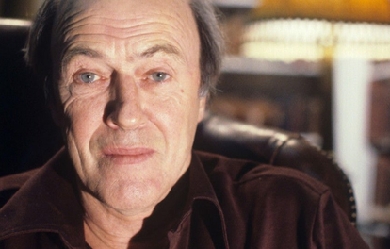

Roald Dahl was a British novelist, short story writer, poet, screenwriter, and fighter pilot. His books have sold over 200 million copies worldwide. Born in Wales to Norwegian parents, Dahl served in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War, in which he became a flying ace and intelligence officer, rising to the rank of acting wing commander. He rose to prominence in the 1940s with works for both children and adults and he became one of the world’s best-selling authors. He has been referred to as "one of the greatest storytellers for children of the 20th century". His awards for contribution to literature include the 1983 World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement, and the British Book Awards’ Children’s Author of the Year in 1990. In 2008, The Times placed Dahl 16th on its list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".

my name shaqueria and poetry is my life i write all the time . its a way of expressing myself and my inner feelings i mostly write about reality and the real world like things thats goes on in life. really looking forward to making this writing my carreer, i write songs lyrics books and poetry of course im a nice outgoing person and my life is bascally in my poetry I dont really know how to speak or explain how i feel inless im putting it in words, my writing is my life i started when i was 10 i use to always rap and sing bt poetry found its way to my heart and stayed there i like reading other people poetry to see if there words could relate to mind. i was scared for the longest to put anything i wrote up because i thought people would judge me and i want get no where but to be judges put you in the right spot and actually open up your opp. because someone out there would like what you can created. i found out you would be rejected by some but it could also change someones life by my story and im hoping to. ill like you yall would leave some feedback on my poems tell me whats right whats wrong and how yall feel about what i have writing ..........THANK YOUU

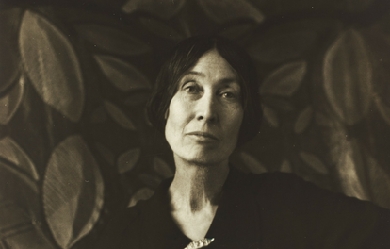

Lola Ridge, born Rose Emily Ridge (12 December 1873 Dublin—19 May 1941 Brooklyn) was an Irish-American anarchist poet and an influential editor of avant-garde, feminist, and Marxist publications. She is best remembered for her long poems and poetic sequences, published in numerous magazines and collected in five books of poetry. Along with other political poets of the early Modernist period, Ridge has received renewed critical attention since the beginning of the 21st century and is praised for making poetry directly from harsh urban life. A new selection of her poetry was published in 2007 and a biography in 2016.

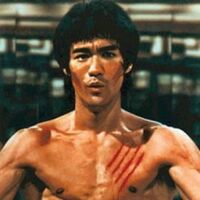

Bruce Jun Fan Lee was born in the hour of the Dragon, between 6 and 8 a.m., in the year of the Dragon on November 27, 1940 at the Jackson Street Hospital in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Today, a plaque in the hospital’s entry commemorates the place of his birth. Bruce’s birth, in the hour and the year of the Dragon, is a powerful symbol in Chinese astrology. It would be a strong omen of the powerful life that was to be lived by Bruce Lee and the explosive impact his life would have on countless others. Bruce was the fourth child born to Lee Hoi Chuen and his wife Grace Ho. He had two older sisters, Phoebe and Agnes, an older brother, Peter, and a younger brother, Robert. Lee Hoi Chuen was, by profession, a comedian in the Chinese opera and an actor in Cantonese films. At the time Bruce was born, Mr. and Mrs. Lee were on tour with the opera company in the United States. Thus, it was fortuitous for Bruce’s future that his birth took place in America, as he would return 18 years later to claim his birthright of American citizenship. Bruce’s parents gave him the name “Jun Fan.” Since it is Chinese custom to put the surname first, Bruce’s full name is written Lee Jun Fan. The true meaning of Jun Fan deserves an explanation as it, too, would foretell the journey of the newly born Lee son. Literally, JUN means “to arouse to the active state” or “to make prosperous.” It was a common middle name used by Hong Kong Chinese boys in those days, understandably because China and the Chinese people were very vulnerable at that time, and everyone, including Bruce’s parents, wanted the “sleeping lion of the East” to wake up. The FAN syllable refers to the Chinese name for San Francisco, but its true meaning is “fence of a garden” or “bordering subordinate countries of a big country.” During the period of the Ching Dynasty (1644-1911), many Chinese immigrated to Hawaii and San Francisco as laborers, and the implication became that the United States was FAN of the Great Ching Empire. Thus the true meaning of Bruce’s name--JUN FAN--was “to arouse and make FAN (the United States) prosperous.” The gut feeling of many Chinese at that time, who felt suppressed by and inferior to foreign powers, was that they wished to outshine the more superior countries and regain the Golden Age of China. Bruce’s parents wanted Bruce to have his name shine and shake the foreign countries, which he certainly succeeded in doing. The English name, BRUCE, was given to the baby boy by a nurse in the Jackson Street Hospital although he was never to use this name until he entered secondary school and began his study of the English language. The story goes that on the first day of English class, the students were asked to write down their English names, and Bruce, not knowing his name, copied the name of the student next to him. His family almost never used the name Bruce, especially in his growing up years when his nickname in the family was “SAI FON,” which literally means Little Peacock. This is a girl’s nickname, but in being applied to Bruce, it had a serious purpose. The first-born child of Mr. and Mrs. Lee had been a boy who did not survive infancy. Their belief was that if the gods did not favor the birth of a male child, the babe might be taken away. Thus, the name, Little Peacock, was used as a ruse to fool the gods into thinking that Bruce was a girl. It was a term of great affection within the family circle. At the age of three months, Lee Hoi Chuen, his wife Grace and baby Bruce returned to Hong Kong where Bruce would be raised until the age of 18. Probably because of the long ocean voyage and the change in climates, Bruce was not a strong child in his very early years, a condition that would change when he took up the study of gung fu at the age of 13. (Bruce always spelled his Chinese martial art as GUNG FU, which is the Cantonese pronunciation of the more commonly spelled Kung Fu, a Mandarin pronunciation.) Bruce’s most prominent memory of his early years was the occupation of Hong Kong by the Japanese during the World War II years (1941-1945). The residence of the Lee family was a flat at 218 Nathan Road in Kowloon directly across the street from the military encampment of the Japanese. Bruce’s mother often told the story of young Bruce, less than 5 years old, leaning precariously off the balcony of their home raising his fist to the Japanese Zeros circling above. Another nickname the family often applied to Bruce was “Mo Si Ting” which means “never sits still” and aptly described his personality. The Japanese occupation was Bruce’s first prescient memory, but Hong Kong had been a British Crown Colony since the late 1800’s. The English returned to power at the end of the war. It is not hard to see why young Bruce would have rebellious feelings toward foreign usurpation of his homeland. In his teenage years Bruce was exposed to the common practice of unfriendly taunting by English school boys who appeared to feel superior to the Chinese. It is not surprising that Bruce and his friends retaliated by returning the taunts and sometimes getting into fights with the English boys. This atmosphere laid the background for Bruce to begin his study of martial arts. At the age of 13, Bruce was introduced to Master Yip Man, a teacher of the Wing Chun style of gung fu. For five years Bruce studied diligently and became very proficient. He greatly revered Yip Man as a master teacher and wise man and frequently visited with him in later years. When he first took up gung fu, he used his new skills to pummel his adversaries, but it did not take long for Bruce to learn that the real value of martial arts training is that the skills of physical combat instill confidence to the point that one does not feel the constant need to defend one’s honor through fighting. In high school, Bruce, now no longer a weak child, was beginning to hone his body through hard training. One of his accomplishments was winning an interschool Boxing Championship against an English student in which the Marquis of Queensbury rules were followed and no kicking was allowed. Given the graceful movements, which would later be spectacularly displayed in his films, it is no surprise that Bruce was also a terrific dancer, and in 1958 he won the Hong Kong Cha Cha Championship. He studied dancing as assiduously as he did gung fu, keeping a notebook in which he had noted 108 different cha cha steps. It is easy to see that Bruce possessed the traits of self-discipline and hard work which would later hold him in good stead, even though at this stage he was not among the best academic students in the class. In addition to his studies, gung fu and dancing, Bruce had another side interest during his school years. He was a child actor under the tutelage of his father who must have known from an early age that Bruce had a streak of showmanship. Bruce’s very first role was as a babe in arms as he was carried onto the stage. By the time he was 18, he had appeared in 20 films. In those days movie making was not particularly glamorous or remunerative in Hong Kong, but Bruce loved acting. His mother often told stories of how Bruce was impossible to wake up to go to school, but just a tap on the shoulder at midnight would rouse him from his bed to go to the film studio. Movies were most often made at night in Hong Kong in order to minimize the sounds of the city. (See Filmography) At the age of 18, Bruce was looking for new vistas in his life, as were his parents who were discouraged that Bruce had not made more progress academically. It was common practice for high school graduates to go overseas to attend colleges, but that required excellent grades. Bruce’s brother and sister had come to the United States on student visas for their higher education. Although Bruce had not formally graduated from high school, and was more interested in gung fu, dancing and acting, his family decided that it was time for him to return to the land of his birth and find his future there. In April of 1959, with $100 in his pocket, Bruce boarded a steamship in the American Presidents Line and began his voyage to San Francisco. His passage was in the lower decks of the ship, but it didn’t take long for Bruce to be invited up to the first class accommodations to teach the passengers the cha cha. Landing in San Francisco, Bruce was armed with the knowledge that his dancing abilities might provide him a living, so his first job was as a dance instructor. One of his first students was Bob Lee, brother of James Y. Lee, who would become Bruce’s great friend, colleague in the martial arts, and eventually partner and Assistant Instructor of the Oakland Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute. Bruce did not stay long in San Francisco, but traveled to Seattle where a family friend, Ruby Chow, had a restaurant and had promised Bruce a job and living quarters above the restaurant. By now Bruce had left his acting and dancing passions behind and was intent on furthering his education. He enrolled at Edison Technical School where he fulfilled the requirements for the equivalent of high school graduation and then enrolled at the University of Washington. Typical of his personality traits, he attacked learning colloquial English as he had his martial arts training. Not content to speak like a foreigner, he applied himself to learning idiosyncrasies of speech. His library contained numerous books, underlined and dog-eared on common English idiomatic phrases. Although he never quite lost the hint of an English accent when speaking, his ability to turn a phrase or “be cool” was amazing for one who did not speak a word of the language until the age of 12. Bruce’s written English skills exceeded his spoken language abilities at first because he had been well tutored in the King’s proper English prose in Hong Kong. When his wife-to-be met him at the University of Washington, he easily edited her English papers for correct grammar and syntax. At the university, Bruce majored in philosophy. His passion for gung fu inspired a desire to delve into the philosophical underpinnings of the arts. Many of his written essays during those years would relate philosophical principles to certain martial arts techniques. For instance, he wrote often about the principles of yin and yang and how they could translate into hard and soft physical movements. In this way he was completing his education as a true martial artist in the time-honored Chinese sense of one whose knowledge encompasses the physical, mental and spiritual aspects of the arts. In the three years that Bruce studied at the university, he supported himself by teaching gung fu, having by this time given up working in the restaurant, stuffing newspapers or various other odd jobs. He and a few of his new friends would meet in parking lots, garages or any open space and play around with gung fu techniques. In the late ‘50’s and early ‘60’s, “gung fu” was an unknown term; in fact, the only physical art that might be listed in the yellow pages was Judo. Even the name “karate” was not a familiar term. The small group of friends was intrigued by this art called gung fu. One of the first students in this group was Jesse Glover who continues to teach some of Bruce’s early techniques to this day. It was during this period that Bruce and Taky Kimura became friends. Not only would Taky become Bruce’s gung fu student and the first Assistant Instructor he ever had, but the friendship forged between the two men was a source of love and strength for both of them. Taky Kimura has continued to be Bruce’s staunch supporter, devoting endless hours to preserving his art and philosophy throughout the 30 years since Bruce’s passing. The small circle of friends that Bruce had made encouraged him to open a real school of gung fu and charge a nominal sum for teaching in order to support himself while attending school. Renting a small basement room with a half door entry from 8th Street in Seattle’s Chinatown, Bruce decided to call his school the Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute. In 1963, having established a dedicated group of students and having given numerous demonstrations at the university, Bruce thought he might attract more students by opening a larger school at 4750 University Way where he also lived in a small room in the back of the kwoon. One of his students in 1963 was a freshman at the University of Washington, Linda Emery. Linda knew who Bruce was from his guest lectures in Chinese philosophy at Garfield High School, and in the summer after graduating, at the urging of her Chinese girlfriend, SueAnn Kay, Linda started taking gung fu lessons. It wasn’t long before the instructor became more interesting than the lessons. Bruce and Linda were married in 1964. By this time, Bruce had decided to make a career out of teaching gung fu. His plan involved opening a number of schools around the country and training assistant instructors to teach in his absence. Leaving his Seattle school in the hands of Taky Kimura, Bruce and Linda moved to Oakland where Bruce opened his second school with James Lee. The two men had formed a friendship over the years with each traveling frequently between Seattle and Oakland. James was a gung fu man from way back, but when he saw Bruce’s stuff he was so impressed that he wanted to join with him in starting a school. Thus the second branch of the Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute was founded. Having now been in the United States for five years, Bruce had left behind any thought of acting as a career, and devoted himself completely to his choice of martial arts as a profession. Up to this time Bruce’s gung fu consisted mostly of wing chun techniques and theory he had learned from Yip Man. Gradually though, because of his burgeoning interest in the philosophy of martial arts and his desire for self improvement, he was expanding his repertoire. A particular incident accelerated his process of self-exploration. In 1964 Bruce was challenged by some gung fu men from San Francisco who objected to his teaching of non-Chinese students. Bruce accepted the challenge and the men arrived at the kwoon in Oakland on the appointed day for the face off. The terms were that if Bruce were defeated he would stop teaching the non Chinese. It was a short fight with the gung fu man from The City giving up when Bruce had him pinned to the floor after about three minutes. The significance of this fight was that Bruce was extremely disappointed in his own performance. Even though he had won, he was winded and discouraged about his inability to put the man away in under three minutes. This marked a turning point for Bruce in his exploration of his martial art and the enhancement of his physical fitness. Thus began the evolution of Jeet Kune Do. Just as Bruce was cementing his plans to expand his martial arts schools, fate stepped in to move his life in another direction. In the preceding years Bruce had made the acquaintance of Ed Parker, widely regarded as the father of American Kenpo. In August of 1964, Ed invited Bruce to Long Beach, CA to give a demonstration at his First International Karate Tournament. Bruce’s exhibition was spectacular. He used Taky as his partner and demonstrated his blindfolded chi sao techniques. At one point he used a member of the audience to show the power of his one-inch punch. Such was Bruce’s charisma that he spoke conversationally, injecting humor into his comments while at the same time emphatically demonstrating his power, precision and speed. A member of the audience was Jay Sebring, a well-known hair stylist to the stars. As fate would have it, the following week, Jay was styling the hair of William Dozier, an established producer. Mr. Dozier mentioned to Jay that he was looking for an actor to play the part of Charlie Chan’s son in a series to be entitled, “Number One Son.” Jay told the producer about having seen this spectacular young Chinese man giving a gung fu demonstration just a few nights before. Mr. Dozier obtained a copy of the film that was taken at Ed Parker’s tournament. The next week he called Bruce at home in Oakland and invited him to come to Los Angeles for a screen test. Bruce’s screen test was impressive, but in the meantime plans for “Number One Son” had been scuttled. Mr. Dozier was now immersed in the production of the “Batman” TV series, but still he wanted to hang onto Bruce. The plan was that if Batman was successful for more than one season, then Dozier wanted to capitalize on the popularity of another comic book character, “The Green Hornet” with Bruce playing the part of Kato. To keep Bruce from signing with someone else, Mr. Dozier paid him an $1,800 option for one year. About this time things were changing in Bruce’s personal life as well. His own number one son, Brandon Bruce Lee, was born February 1, 1965. One week later Bruce’s father, Lee Hoi Chuen, died in Hong Kong. Bruce was pleased that his father had known about the birth of the first grandchild in the Lee family. Given these events and the arrival of the lump sum option money, Bruce decided it was time to make a trip to Hong Kong to visit his mother and introduce the family to both Linda and Brandon. They stayed in the family flat on Nathan Road for four months. While there Bruce was able to “play gung fu” with Master Yip Man and the students of the wing chun school. Upon leaving Hong Kong, Bruce and his family traveled to Seattle where they stayed with Linda’s family for another four months. During this time Bruce spent a great deal of time with Taky and the students at the Seattle school. After Seattle, the family moved back to James Lee’s house in Oakland for several months before making the move to Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, he got better acquainted with Dan Inosanto whom he had known through Ed Parker. It was not long before Bruce opened his third gung fu school with Dan as his assistant instructor During this entire year of traveling and working closely with his best gung fu colleagues, Bruce was going through a period of intense self-exploration. Bruce was always a goal setter. However, he was never obstinate about his goals and if the wind changed, he could steer his life on a different course. He was in a period of transition at this time, deciding whether to make acting his career or continue on the path of opening nationwide schools of gung fu. His decision was to focus on acting and see if he could turn it into a productive career. He often said his passion was pursuit of the martial arts, but his career choice was filmmaking. The chief reason that Bruce turned his attention to acting was that he had lost interest in spreading his way of martial arts in a wide scale manner. He had begun to see that if his schools became more numerous, he would lose control of the quality of the teaching. Bruce loved to teach gung fu, and he loved his students. Countless hours were spent in his backyard or in the kwoon, one on one with students. They were like members of the family. His love for his martial arts was not something he wanted to turn into a business. In 1966, production started on “The Green Hornet.” The filming lasted for six months, the series for one season, and that was the end of it. Bruce’s take home pay was $313 a week, which seemed like a lot of money at the time. When they first started filming, the cameras were not able to record the fight scenes clearly because of Bruce’s speed. They asked him to slow down to capture the action. Bruce’s gung fu moves thrilled audiences, and the series became a sought-after collector item in later years. Bruce maintained a friendship with Van Williams who played the part of Britt Reid. The years between 1967 and 1971 were lean years for the Lee family. Bruce worked hard at furthering his acting career and did get some roles in a few TV series and films. (See Filmography) To support the family, Bruce taught private lessons in Jeet Kune Do, often to people in the entertainment industry. Some of his clients included Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Stirling Silliphant, Sy Weintraub, Ted Ashley, Joe Hyams, James Garner and others. A great blessing was the arrival of a daughter, Shannon Emery Lee, on April 19, 1969. She brought great joy into the Lee household and soon had her daddy around her little finger. During this time Bruce continued the process he had started in Oakland in 1964, the evolution of his way of martial arts, which he called Jeet Kune Do, “The Way of The Intercepting Fist.” He read and wrote extensively his thoughts about physical combat, the psychology of fighting, the philosophical roots of martial arts, and about motivation, self-actualization and liberation of the individual. Thanks to this period in his life, which was at times frustrating, we know more about the mind of Bruce Lee through his writings. Bruce was devoted to physical culture and trained devotedly. In addition to actual sparring with his students, he believed in strenuous aerobic workouts and weight training. His abdominal and forearm workouts were particularly intense. There was rarely a time when Bruce was doing nothing—in fact, he was often seen reading a book, doing forearm curls and watching a boxing film at the same time. He also paid strict attention to his food consumption and took vitamins and Chinese herbs at times. It was actually his zealousness that led to an injury that was to become a chronic source of pain for the rest of his life. On a day in 1970, without warming up, something he always did, Bruce picked up a 125-pound barbell and did a “good morning” exercise. That consists of resting the barbell on one’s shoulders and bending straight over at the waist. After much pain and many tests, it was determined that he had sustained an injury to the fourth sacral nerve. He was ordered to complete bed rest and told that undoubtedly he would never do gung fu again. For the next six months, Bruce stayed in bed. It was an extremely frustrating, depressing and painful time, and a time to redefine goals. It was also during this time that he did a great deal of the writing that has been preserved. After several months, Bruce instituted his own recovery program and began walking, gingerly at first, and gradually built up his strength. He was determined that he would do his beloved gung fu again. As can be seen by his later films, he did recover full use of his body, but he constantly had to take measures like icing, massage and rest to take care of his back. Bruce was always imagining story ideas. One of the projects he had been working on was the idea of a television series set in the Old West, featuring an Eastern monk who roamed the countryside solving problems. He pitched the idea at Warner Bros. and it was enthusiastically received. The producers talked at great length to Bruce about the proposed series always with the intent that Bruce would play the role of the Eastern wise man. In the end, the role was not offered to Bruce; instead it went to David Carradine. The series was “Kung Fu.” The studio claimed that a Chinese man was not a bankable star at that time. Hugely disappointed, Bruce sought other ways to break down the studio doors. Along with two of his students, Stirling Silliphant, the famed writer, and actor, James Coburn, Bruce collaborated on a script for which he wrote the original story line. The three of them met weekly to refine the script. It was to be called “The Silent Flute.” Again, Warner Bros. was interested and sent the three to India to look for locations. Unfortunately the right locations could not be found, the studio backed off, and the project was put on the back burner. Thwarted again in his effort to make a go of his acting career, Bruce devised a new approach to his goal. In 1970, when Bruce was getting his strength back from his back injury, he took a trip to Hong Kong with son Brandon, age five. He was surprised when he was greeted as “Kato,” the local boy who had been on American TV. He was asked to appear on TV talk shows. He was not aware that Hong Kong film producers were viewing him with interest. In 1971, about the time that “The Silent Flute” failed to materialize, Hong Kong producer Raymond Chow contacted Bruce to interest him in doing two films for Golden Harvest. Bruce decided to do it, reasoning that if he couldn’t enter the front door of the American studios, he would go to Hong Kong, establish himself there and come back in through the side door. In the summer of 1971, Bruce left Los Angeles to fly to Hong Kong, then on to Thailand for the making of “The Big Boss,” later called “Fists of Fury.” Between Hong Kong and Thailand, producer Run Run Shaw attempted to intercede and woo Bruce away from Golden Harvest. But Bruce had signed a deal so he stayed with Raymond Chow. Bruce’s family did not accompany him on this trip because the village where the film was made was not suitable for small children. It was also felt that if this film was not a hit, Bruce might be back in L.A. sooner than expected. Although the working conditions were difficult, and the production quality substandard to what Bruce was accustomed, “The Big Boss” was a huge success. The premier took place at midnight, as was Hong Kong custom. Chinese audiences are infamous for expressing their emotions during films—both positive and negative. The entire cast and production team were very nervous, no one more so than Bruce. At the end of the showing, the entire audience was silent for a moment, then erupted in cheers and hailed their new hero who was viewing from the back of the theater. In September of 1971, with filming set to commence on the second of the contractual films, Bruce moved his family over to Hong Kong and prepared to sell their Los Angeles home. “Fist of Fury,” also called “Chinese Connection” was an even bigger success than the first film breaking all-time box office records. Now that Bruce had completed his contract with Golden Harvest, and had become a bankable commodity, he could begin to have more input into the quality of his films. For the third film, he formed a partnership with Raymond Chow, called Concord Productions. Not only did Bruce write “The Way of the Dragon,” also called “Return of the Dragon,” but he directed and produced it as well. Once again, the film broke records and now, Hollywood was listening. In the fall of 1972, Bruce began filming “The Game of Death,” a story he once again envisioned. The filming was interrupted by the culmination of a deal with Warner Bros. to make the first ever Hong Kong-American co-production. The deal was facilitated mainly by Bruce’s personal relationship with Warner Bros. president, Ted Ashley and by Bruce’s successes in Hong Kong. It was an exciting moment and a turning point in Hong Kong’s film industry. “The Game of Death” was put on hold to make way for the filming of “Enter the Dragon.” Filming “Enter the Dragon” was not an easy undertaking. The American cast and crew and their Chinese counterparts experienced language problems and production difficulties. It was a stressful time for Bruce too as he wanted the film to be especially good and well accepted by Western audiences. “Enter the Dragon” was due to premier at Hollywood’s Chinese theater in August of 1973. Unfortunately, Bruce would not live to see the opening of his film, nor would he experience the accumulated success of more than thirty years of all his films’ popularity. On July 20, 1973, Bruce had a minor headache. He was offered a prescription painkiller called Equagesic. After taking the pill, he went to lie down and lapsed into a coma. He was unable to be revived. Extensive forensic pathology was done to determine the cause of his death, which was not immediately apparent. A nine-day coroner’s inquest was held with testimony given by renowned pathologists flown in from around the world. The determination was that Bruce had a hypersensitive reaction to an ingredient in the pain medication that caused a swelling of the fluid on the brain, resulting in a coma and death. The world lost a brilliant star and an evolved human being that day. His spirit remains an inspiration to untold numbers of people around the world. Copyright @ 2006 Bruce Lee Foundation References Bruce Lee Foundation - http://bruceleefoundation.com/index.cfm/pid/10585

Amable Tastu, nom de plume de Sabine Casimire Amable Voïart, née le 31 août 1798 à Metz et morte le 10 janvier 1885 à Palaiseau, est une femme de lettres française. Biographie Sabine Casimire Amable Voïart, née rue des clercs à Metz, est la fille de l’administrateur aux vivres de l’armée Jacques-Philippe Voïart et de Jeanne-Amable Bouchotte, sœur du ministre de la guerre, Jean-Baptiste Bouchotte. Elle perd sa mère en 1802 et en 1806, son père se remarie avec Anne-Élisabeth-Élise Petitpain, femme de lettres de Nancy qui partage avec Amable sa connaissance de l’anglais, de l’allemand et de l’italien. En 1816, elle épouse l’imprimeur perpignanais Joseph Tastu qui la trompe. Un an plus tard, elle met au monde un fils, Eugène. L’année suivante, en 1819, son mari quitte Perpignan et se rend à Paris pour reprendre l’imprimerie libérale des frères Beaudouin, au no 36 rue de Vaugirard. Sous son nom de plume d’Amable Tastu, elle écrit et publie des poèmes qui lui apportent la notoriété. C’est la muse romantique par excellence. En 1851, la rose Amable Tastu est créée en hommage. Après des années de prospérité, les affaires de son mari déclinent. La crise économique de 1830 a raison de son imprimerie et il fait faillite. Amable abandonne alors la poésie pour se livrer à des productions alimentaires afin de subvenir aux besoins de sa famille. Christine Planté précise: « Elle dut vivre de sa plume en rédigeant des travaux alimentaires pour combler l’indigence de son mari ruiné par la révolution de Juillet et inapte à se refaire ». Elle collabore régulièrement au Mercure de France et à La Muse française. Elle publie des ouvrages pédagogiques, des traductions, des sommes historiques, un Cours d’histoire de France, publié en accord avec le ministre de l’Instruction publique, un volume sur la littérature allemande, un autre sur la littérature italienne. Elle est également l’auteure de libretti pour des musiciens comme Saint-Saëns. En 1849, après la mort de son mari, elle suit son fils Eugène dans ses missions diplomatiques à Chypre et à Bagdad. En 1866, elle revient pour quelques années à Paris. En 1871, elle s’installe à Palaiseau où elle continue à mener une intense vie sociale et y meurt le 10 janvier 1885. Relations Elle est très appréciée de Lamartine, Sainte Beuve, Hugo, Chateaubriand, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore. Victor Hugo lui dédie son Moïse sur le Nil et Chateaubriand son Camoens. Sainte-Beuve compose en son honneur une élégie de 18 quatrains et lui consacre 16 pages dans ses Portraits contemporains.