Henry Kirke White (21 March 1785– 19 October 1806) was an English poet, who died at a young age. Life White was born in Nottingham, the son of a butcher, a trade for which he was himself intended. However, he was greatly attracted to book-learning. By age seven, he was giving reading lessons (unbeknownst to the rest of the family, being offered after the household were abed) to a family servant. After being briefly apprenticed to a stocking-weaver, he was articled to a lawyer. While in this position, he excelled in studying Latin and Greek. Seeing the results of White’s diligent studies, his master offered to release him from his contract if he had sufficient means to go to college. He received encouragement from Capel Lofft, the friend of Robert Bloomfield, and published in 1803 Clifton Grove, a Sketch in Verse, with other Poems, dedicated to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. The book was violently attacked in the Monthly Review (February 1804), but White was rewarded with a kind letter from Robert Southey. Through the efforts of his friends, he was able to enter St John’s College, Cambridge, having spent a year beforehand with a private tutor, the Rev Lorenzo Grainger at Winteringham, Lincolnshire. Close application to study induced a serious illness, consumption was the disease, according to Sir Harris Nicholas memoir, to which he ultimately became a victim, and to which White made many allusions in his poems and letters. Fears were also entertained for his sanity, but he went into residence at Cambridge, with a view to taking holy orders, in the autumn of 1805. The strain of continuous study proved fatal. He was buried in the church of All Saints Jewry, Cambridge, which stood opposite the gates of St John’s College, but has since been demolished. The genuine piety of his religious verses secured a place in popular hymnology for some of his hymns, in particular the still popular 'O Lord, another day is flown’. Much of his fame was due to sympathy inspired by his early death; but Lord Byron agreed with Southey about the young man’s promise. Robert Southey said of him 'he could not rest satisfied till he had formed his principles upon the basis of Christianity. Literary legacy His Remains, with his letters (which along with White’s poems contain many allusions to himself that they may almost be considered an autobiography ) and an account of his life, were edited (5 vols., 1807–1822) by Robert Southey. See prefatory notices by Sir Harris Nicolas to his Poetical Works (new ed., 1866) in the Aldine Press British poets; by Harry Kirke Swann in the volume of selections (1897) in the Canterbury Poets; and by John Drinkwater to the edition in the “Muses’ Library.” See also John Thomas Godfrey and J. Ward, The Homes and Haunts of Henry Kirke White (1908). Lord Byron said of White in a tributary eulogy 'while life was in its spring, thy young muse just waved her joyous wing’. White’s complete works were published in 1923. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Kirke_White

Francis William Lauderdale Adams (27 September 1862– 4 September 1893) was an essayist, poet, dramatist, novelist and journalist who produced a large volume of work in his short life. He was born in Malta the son of Andrew Leith Adams, an army surgeon, who became afterwards well known as a scientist, a fellow of the Royal Society, and an author of natural history books set in different parts of the British empire. Francis’ mother, Bertha Jane Grundy, became a well-known novelist. Francis was educated at Shrewsbury School and from 1879 served as an attaché in Paris. He took up a teaching position as an assistant master at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight, for two years. He joined the Social Democratic Federation in London in 1883. In 1884 he married Helen Uttley and migrated to Australia where he started work as a tutor on a station at Jerilderie, New South Wales, but soon moved on to Sydney and then Queensland, and dedicated himself to writing.

Receiving my graduate degree from JFK University in Consciousness and the Arts and undergraduate education in Language and Sociology from Howard University, my contributions to society include: improving the status of women in the American Society, consulting on family education and management. Before retiring, I worked as the Secretary for the U.S. Treasury, Proofreader for the Office of the Price Administration and was a Researcher and Public Relations Director for the Eisenhower Congressional Committee. I am now a Professional Volunteer. Some of my achievements are as follows: Senior Senator to the California Senior Legislature Past Presidency and/or Advisor: AAUW, Business and Professional Women, Richmond Plaza Neighborhood Council, Council for Civic Unity, Advisory Council on Aging, Mental Health Task Force on Aging, Elder Abuse Consortium, Ethnic and Handicapped Task Force. I am a proud parent of three children and grandparent of four grandchildren and I share my life with Joe, my husband, who retired as a General Dentist.

Charlotte Brontë (21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855) was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood, whose novels are English literature standards. She wrote Jane Eyre under the pen name Currer Bell. Early life and education Charlotte was born in Thornton, Yorkshire in 1816, the third of six children, to Maria (née Branwell) and her husband Patrick Brontë (formerly surnamed Brunty or Prunty), an Irish Anglican clergyman. In 1820, the family moved a few miles to the village of Haworth, where Patrick had been appointed Perpetual Curate of St Michael and All Angels Church. Charlotte's mother died of cancer on 15 September 1821, leaving five daughters and a son to be taken care of by her sister Elizabeth Branwell. In August 1824, Charlotte was sent with three of her sisters, Emily, Maria, and Elizabeth, to the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge in Lancashire (She used the school as the basis for Lowood School in Jane Eyre). The school's poor conditions, Charlotte maintained, permanently affected her health and physical development and hastened the deaths of her two elder sisters, Maria (born 1814) and Elizabeth (born 1815), who died of tuberculosis in June 1825. Soon after their deaths, her father removed Charlotte and Emily from the school. At home in Haworth Parsonage Charlotte acted as "the motherly friend and guardian of her younger sisters". She and her surviving siblings — Branwell, Emily, and Anne – created their own literary fictional worlds, and began chronicling the lives and struggles of the inhabitants of these imaginary kingdoms. Charlotte and Branwell wrote Byronic stories about their imagined country, "Angria", and Emily and Anne wrote articles and poems about "Gondal". The sagas they created were elaborate and convoluted (and still exist in partial manuscripts) and provided them with an obsessive interest during childhood and early adolescence, which prepared them for their literary vocations in adulthood. Charlotte continued her education at Roe Head in Mirfield, from 1831 to 1832, where she met her lifelong friends and correspondents, Ellen Nussey and Mary Taylor. Shortly after she wrote the novella The Green Dwarf (1833) using the name Wellesley. Charlotte returned to Roe Head as a teacher from 1835 to 1838. In 1839, she took up the first of many positions as governess to families in Yorkshire, a career she pursued until 1841. Politically a Tory, she preached tolerance rather than revolution. She held high moral principles, and, despite her shyness in company, was always prepared to argue her beliefs. Brussels In 1842 Charlotte and Emily travelled to Brussels to enrol in a boarding school run by Constantin Heger (1809–96) and his wife Claire Zoé Parent Heger (1804–87). In return for board and tuition, Charlotte taught English and Emily taught music. Their time at the boarding school was cut short when Elizabeth Branwell, their aunt who joined the family after the death of their mother to look after the children, died of internal obstruction in October 1842. Charlotte returned alone to Brussels in January 1843 to take up a teaching post at the school. Her second stay was not a happy one; she became lonely, homesick and deeply attached to Constantin Heger. She returned to Haworth in January 1844 and used her time at the boarding school as the inspiration for some experiences in The Professor and Villette. First publication In May 1846, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne self-financed the publication of a joint collection of poetry under the assumed names of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. These pseudonyms veiled the sisters' gender whilst preserving their real initials, thus Charlotte was "Currer Bell". "Bell" was the middle name of Haworth's curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls, whom Charlotte later married. On the decision to use noms de plume, Charlotte wrote: Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because — without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called 'feminine' – we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice; we had noticed how critics sometimes use for their chastisement the weapon of personality, and for their reward, a flattery, which is not true praise. Although only two copies of the collection of poetry were sold, the sisters continued writing for publication and began their first novels, continuing to use their noms de plume when sending manuscripts to potential publishers. Jane Eyre Charlotte's first manuscript, The Professor, did not secure a publisher, although she was heartened by an encouraging response from Smith, Elder & Co of Cornhill, who expressed an interest in any longer works which "Currer Bell" might wish to send. Charlotte responded by finishing and sending a second manuscript in August 1847, and six weeks later Jane Eyre: An Autobiography, was published. Jane Eyre was a success, and initially received favourable reviews. There was speculation about the identity of Currer Bell, and whether Bell was a man or a woman. The speculation heightened on the subsequent publication of novels by Charlotte's sisters: Emily's Wuthering Heights by "Ellis Bell" and Anne's Agnes Grey by "Acton Bell". Accompanying the speculation was a change in the critical reaction to Charlotte's work; accusations began to be made that Charlotte's writing was "coarse", a judgement which was made more readily once it was suspected that "Currer Bell" was a woman. However sales of Jane Eyre continued to be strong, and may even have increased due to the novel's developing reputation as an 'improper' book. Shirley and family bereavements Following the success of Jane Eyre, in 1848 Charlotte began work on the manuscript of her second novel, Shirley. The manuscript was only partially completed when the Brontë household suffered a tragic turn of events, experiencing the deaths of three family members within eight months. In September 1848 Charlotte's only brother, Branwell, died of chronic bronchitis and marasmus exacerbated by heavy drinking, although Charlotte believed his death was due to tuberculosis. Branwell was a suspected "opium eater", a laudanum addict. Emily became seriously ill shortly after Branwell's funeral, and died of pulmonary tuberculosis in December 1848. Anne died of the same disease in May 1849. Charlotte was unable to write at this time. After Anne's death Charlotte resumed writing as a way of dealing with her grief, and Shirley was published in October 1849. Shirley deals with the themes of industrial unrest and the role of women in society. Unlike Jane Eyre, which is written from the first-person perspective of the main character, Shirley is written in the third-person and lacks the emotional immediacy of Jane Eyre, and reviewers found it less shocking. In society In view of the success of her novels, particularly Jane Eyre, Charlotte was persuaded by her publisher to visit London occasionally, where she revealed her true identity and began to move in a more exalted social circle, becoming friends with Harriet Martineau and Elizabeth Gaskell, and acquainted with William Makepeace Thackeray and G. H. Lewes. She never left Haworth for more than a few weeks at a time as she did not want to leave her ageing father's side. Thackeray’s daughter, the writer Anne Isabella Thackeray Ritchie recalled a visit to her father by Charlotte: …two gentlemen come in, leading a tiny, delicate, serious, little lady, with fair straight hair, and steady eyes. She may be a little over thirty; she is dressed in a little barège dress with a pattern of faint green moss. She enters in mittens, in silence, in seriousness; our hearts are beating with wild excitement. This then is the authoress, the unknown power whose books have set all London talking, reading, speculating; some people even say our father wrote the books – the wonderful books… The moment is so breathless that dinner comes as a relief to the solemnity of the occasion, and we all smile as my father stoops to offer his arm; for, genius though she may be, Miss Brontë can barely reach his elbow. My own personal impressions are that she is somewhat grave and stern, specially to forward little girls who wish to chatter… Every one waited for the brilliant conversation which never began at all. Miss Brontë retired to the sofa in the study, and murmured a low word now and then to our kind governess… the conversation grew dimmer and more dim, the ladies sat round still expectant, my father was too much perturbed by the gloom and the silence to be able to cope with it at all… after Miss Brontë had left, I was surprised to see my father opening the front door with his hat on. He put his fingers to his lips, walked out into the darkness, and shut the door quietly behind him… long afterwards… Mrs. Procter asked me if I knew what had happened… It was one of the dullest evenings [Mrs Procter] had ever spent in her life… the ladies who had all come expecting so much delightful conversation, and the gloom and the constraint, and how finally, overwhelmed by the situation, my father had quietly left the room, left the house, and gone off to his club. Friendship with Elizabeth Gaskell Charlotte sent copies of Shirley to leading authors of the day, including Elizabeth Gaskell. Gaskell and Charlotte met in August 1850 and began a friendship which, whilst not necessarily close, was significant in that Gaskell wrote Charlotte's biography after her death in 1855. The Life of Charlotte Brontë, was published in 1857 and was unusual at the time in that, rather than analysing its subject's achievements, it concentrated on the private details of Charlotte's life, in particular placing emphasis on aspects which countered the accusations of 'coarseness' which had been levelled at Charlotte's writing. Though frank in places, Gaskell was selective about which details she revealed; for example, she suppressed details of Charlotte's love for Heger, a married man, as being too much of an affront to contemporary morals and as a source of distress to Charlotte's still-living friends, father and husband. Gaskell also provided doubtful and inaccurate information about Patrick Brontë, claiming, for example, that he did not allow his children to eat meat. This is refuted by one of Emily Brontë's diary papers, in which she describes the preparation of meat and potatoes for dinner at the parsonage, as Juliet Barker points out in her biography, The Brontës. It has been argued that the particular approach of Mrs Gaskell transferred the focus of attention away from the 'difficult' novels, not just of Charlotte but all the sisters, and began a process of sanctification of their private lives. Villette Charlotte's third published novel, and the last to be published during her lifetime, was Villette, which came out in 1853. Its main themes include isolation, how such a condition can be borne, and the internal conflict brought about by societal repression of individual desire. Its main character, Lucy Snowe, travels abroad to teach in a boarding school in the fictional town of Villette, where she encounters a culture and religion different to her own, and where she falls in love with a man ('Paul Emanuel') whom she cannot marry. Her experiences result in her having a breakdown, but eventually she achieves independence and fulfilment in running her own school. Villette marked Charlotte's return to writing from a first-person perspective (that of Lucy Snowe), a technique she had used successfully in Jane Eyre. Another similarity to Jane Eyre was Charlotte's use of aspects from her own life as inspiration for fictional events, in particular reworking her time spent at the pensionnat in Brussels into Lucy spending time teaching at the boarding school, and falling in love with Constantin Heger into Lucy falling in love with 'Paul Emanuel'. Villette was acknowledged by the critics of the day as a potent and sophisticated piece of writing, although it was criticised for its 'coarseness' and not suitably 'feminine' in its portrayal of Lucy's desires. Illness and subsequent death In June 1854, Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father's curate and possibly the model for Jane Eyre's St. John Rivers. She became pregnant soon after the marriage. Her health declined rapidly during this time, and according to Gaskell, she was attacked by "sensations of perpetual nausea and ever-recurring faintness." Charlotte died, with her unborn child, on 31 March 1855, at the age of 38. Her death certificate gives the cause of death as phthisis (tuberculosis), but many biographers[who?] suggest she may have died from dehydration and malnourishment, caused by excessive vomiting from severe morning sickness or hyperemesis gravidarum. There is evidence to suggest that Charlotte died from typhus she may have caught from Tabitha Ackroyd, the Brontë household's oldest servant, who died shortly before her. Charlotte was interred in the family vault in the Church of St Michael and All Angels at Haworth. Posthumously, her first-written novel was published in 1857. The fragment she worked on in her last years in 1860 has been twice completed by recent authors, the more famous version being Emma Brown: A Novel from the Unfinished Manuscript by Charlotte Brontë by Clare Boylan in 2003. Much Angria material has appeared in published form since the author's death.

William Henry Ogilvie (21 August 1869– 30 January 1963) was a Scottish-Australian narrative poet and horseman. He was born near Kelso, Borders, Scotland and arrived in Australia in 1889, returning to Scotland after a decade. He had a deep love of horses and riding and he became interested in the outback. Before long he became an expert station hand, drover and horse breaker, working on such stations as Belalie on the Warrego, and Maaoupe near Penola in South Australia. He was a friend of Harry “Breaker” Morant and was described as a quiet-spoken Scot of medium height, with a fair moustache and red complexion.

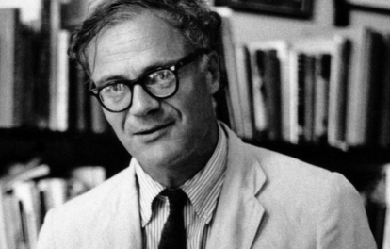

In 1917, Robert Lowell was born into one of Boston's oldest and most prominent families. He attended Harvard College for two years before transferring to Kenyon College, where he studied poetry under John Crowe Ransom and received an undergraduate degree in 1940. He took graduate courses at Louisiana State University where he studied with Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks. His first and second books, Land of Unlikeness (1944) and Lord Weary's Castle (for which he received a Pulitzer Prize in 1947, at the age of thirty), were influenced by his conversion from Episcopalianism to Catholicism and explored the dark side of America's Puritan legacy. Under the influence of Allen Tate and the New Critics, he wrote rigorously formal poetry that drew praise for its exceptionally powerful handling of meter and rhyme. Lowell was politically involved—he became a conscientious objector during the Second World War and was imprisoned as a result, and actively protested against the war in Vietnam—and his personal life was full of marital and psychological turmoil. He suffered from severe episodes of manic depression, for which he was repeatedly hospitalized. Partly in response to his frequent breakdowns, and partly due to the influence of such younger poets as W. D. Snodgrass and Allen Ginsberg, Lowell in the mid-fifties began to write more directly from personal experience, and loosened his adherence to traditional meter and form. The result was a watershed collection, Life Studies (1959), which forever changed the landscape of modern poetry, much as Eliot's The Waste Land had three decades before. Considered by many to be the most important poet in English of the second half of the twentieth century, Lowell continued to develop his work with sometimes uneven results, all along defining the restless center of American poetry, until his sudden death from a heart attack at age 60. Robert Lowell served as a Chancellor of The Academy of American Poets from 1962 until his death in 1977. Poetry Land of Unlikeness (1944) Lord Weary's Castle (1946) Poems, 1938-1949 (1950) The Mills of the Kavanaughs (1951) Life Studies (1959) Imitations (1961) For the Union Dead (1964) Selected Poems (1965) Near the Ocean (1967) The Voyage and Other Versions of Poems by Baudelaire (1968) Notebooks, 1967-1968 (1969) The Dolphin (1973) For Lizzie and Harriet (1973) History (1973) Selected Poems (1976) Day by Day (1977) Prose The Collected Prose (1987) Anthology Phaedra (1961) Prometheus Bound (1969) Drama The Old Glory (1965) References Poets.org - www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/10

Michael Drayton (1563– 23 December 1631) was an English poet who came to prominence in the Elizabethan era. Early life Drayton was born at Hartshill, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. Almost nothing is known about his early life, beyond the fact that in 1580 he was in the service of Thomas Goodere of Collingham, Nottinghamshire. Nineteenth– and twentieth-century scholars, on the basis of scattered allusions in his poems and dedications, suggested that Drayton might have studied at the University of Oxford, and been intimate with the Polesworth branch of the Goodere family. More recent work has cast doubt on those speculations. Literary career 1591–1602 In 1591 he produced his first book, The Harmony of the Church, a volume of spiritual poems, dedicated to Lady Devereux. It is notable for a version of the Song of Solomon, executed with considerable richness of expression. However, with the exception of forty copies, seized by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the whole edition was destroyed by public order. Nevertheless, Drayton published a vast amount within the next few years. In 1593 appeared Idea: The Shepherd’s Garland, a collection of nine pastorals, in which he celebrated his own love-sorrows under the poetic name of Rowland. The basic idea was expanded in a cycle of sixty-four sonnets, published in 1594, under the title of Idea’s Mirror, by which we learn that the lady lived by the river Ankor in Warwickshire. It appears that he failed to win his “Idea,” and lived and died a bachelor. It has been said Drayton’s sonnets possess a direct, instant, and universal appeal, by reason of their simple straightforward ring and foreshadowed the smooth style of Fairfax, Waller, and Dryden. Drayton was the first to bring the term ode, for a lyrical poem, to popularity in England and was a master of the short, staccato Anacreontics measure. Also in 1593 there appeared the first of Drayton’s historical poems, The Legend of Piers Gaveston, and the next year saw the publication of Matilda, an epic poem in rhyme royal. It was about this time, too, that he brought out Endimion and Phoebe, a volume which he never republished, but which contains some interesting autobiographical matter, and acknowledgments of literary help from Thomas Lodge, if not from Edmund Spenser and Samuel Daniel also. In his Fig for Momus, Lodge reciprocated these friendly courtesies. In 1596 Drayton published his long and important poem Mortimeriados, a very serious production in ottava rima. He later enlarged and modified this poem, and republished it in 1603 under the title of The Barons’ Wars. In 1596 also appeared another historical poem, The Legend of Robert, Duke of Normandy, with which Piers Gaveston was reprinted. In 1597 appeared England’s Heroical Epistles, a series of historical studies, in imitation of those of Ovid. These last poems, written in the heroic couplet, contain some of the finest passages in Drayton’s writings. 1603–1631 By 1597, the poet was resting on his laurels. It seems that he was much favoured at the court of Elizabeth, and he hoped that it would be the same with her successor. But when, in 1603, he addressed a poem of compliment to James I, on his accession, it was ridiculed, and his services rudely rejected. His bitterness found expression in a satire, The Owl (1604), but he had no talent in this kind of composition. Not much more entertaining was his scriptural narrative of Moses in a Map of his Miracles, a sort of epic in heroics printed the same year. In 1605 Drayton reprinted his most important works, his historical poems and the Idea, in a single volume which ran through eight editions during his lifetime. He also collected his smaller pieces, hitherto unedited, in a volume undated, but probably published in 1605, under the title of Poems Lyric and Pastoral; these consisted of odes, eclogues, and a fantastic satire called The Man in the Moon. Some of the odes are extremely spirited. In this volume he printed for the first time the famous Ballad of Agincourt. He had adopted as early as 1598 the extraordinary resolution of celebrating all the points of topographical or antiquarian interest in the island of Great Britain, and on this laborious work he was engaged for many years. At last, in 1613, the first part of this vast work was published under the title of Poly-Olbion, eighteen books being produced, to which the learned Selden supplied notes. The success of this great work, which has since become so famous, was very small at first, and not until 1622 did Drayton succeed in finding a publisher willing to undertake the risk of bringing out twelve more books in a second part. This completed the survey of England, and the poet, who had hoped “to crown Scotland with flowers,” and arrive at last at the Orcades, never crossed the Tweed. In 1627 he published another of his miscellaneous volumes, and this contains some of his most characteristic writing. It consists of the following pieces: The Battle of Agincourt, an historical poem in ottava rima (not to be confused with his ballad on the same subject), and The Miseries of Queen Margaret, written in the same verse and manner; Nimphidia, the Court of Faery, a most joyous and graceful little epic of fairyland; The Quest of Cinthia and The Shepherd’s Sirena, two lyrical pastorals; and finally The Moon Calf, a sort of satire. Nimphidia is the most critically acclaimed, along with his famous ballad on the battle of Agincourt; it is quite unique of its kind and full of rare fantastic fancy. The last of Drayton’s voluminous publications was The Muses’ Elizium in 1630. He died in London, was buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, and had a monument placed over him by the Countess of Dorset, with memorial lines attributed to Ben Jonson. Theatre Like other poets of his era, Drayton was active in writing for the theatre; but unlike Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, or Samuel Daniel, he invested little of his art in the genre. For a period of only five years, from 1597 to 1602, Drayton was a member of the stable of playwrights who supplied material for the theatrical syndicate of Philip Henslowe. Henslowe’s Diary links Drayton’s name with 23 plays from that period, and shows that Drayton almost always worked in collaboration with other Henslowe regulars, like Thomas Dekker, Anthony Munday, and Henry Chettle, among others. Of these 23 plays, only one has survived, that being Part 1 of Sir John Oldcastle, which Drayton composed in collaboration with Munday, Robert Wilson, and Richard Hathwaye. The text of Oldcastle shows no clear signs of Drayton’s hand; traits of style consistent through the entire corpus of his poetry (the rich vocabulary of plant names, star names, and other unusual words; the frequent use of original contractional forms, sometimes with double apostrophes, like “th’adult’rers” or “pois’ned’st”) are wholly absent from the text, suggesting that his contribution to the collaborative effort was not substantial. William Longsword, the one play that Henslowe’s Diary suggests was a solo Drayton effort, was never completed. (Drayton may have preferred the role of impresario to that of playwright; he was one of the lessees of the Whitefriars Theatre, together with Thomas Woodford, nephew of the playwright Thomas Lodge, when it was started in 1608. Around 1606, Drayton was also part of a syndicate that chartered a company of child actors, The Children of the King’s Revels. These may or may not have been the Children of Paul’s under a new name, since the latter group appears to have gone out of existence at about this time. The venture was not a success, dissolving in litigation in 1609.) Friendships Drayton was a friend of some of the most famous men of the age. He corresponded familiarly with Drummond; Ben Jonson, William Browne, George Wither and others were among his friends. There is a tradition that he was a friend of Shakespeare, supported by a statement of John Ward, once vicar of Stratford-on-Avon, that “Shakespear, Drayton and Ben Jonson had a merry meeting, and it seems, drank too hard, for Shakespear died of a feavour there contracted.” In one of his poems, an elegy or epistle to Mr Henry Reynolds, he has left some valuable criticisms on poets whom he had known. That he was a restless and discontented, as well as a worthy, man may be gathered from his own admissions. Editions In 1748 a folio edition of Drayton’s complete works was published under the editorial supervision of William Oldys, and again in 1753 there appeared an issue in four volumes quarto. But these were very unintelligently and inaccurately prepared. A complete edition of Drayton’s works with variant readings was projected by Richard Hooper in 1876, but was never carried to a conclusion; a volume of selections, edited by A. H. Bullen, appeared in 1883. See especially Oliver Elton, Michael Drayton (1906). A complete five-volume edition of Drayton’s work was published by Oxford in 1931-41 (revised 1961), edited by J. William Hebel, K. Tillotson and B. H. Newdigate. That and a two volume edition of Drayton’s poems published at Harvard in 1953, edited by John Buxton, are the only 20th century editions of his poems recorded by the Library of Congress. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Drayton

Lionel Pigot Johnson (15 March 1867– 4 October 1902) was an English poet, essayist and critic. Life Johnson was born at Broadstairs, and educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford, graduating in 1890. He became a Catholic convert in 1891. He lived a solitary life in London, struggling with alcoholism and his repressed homosexuality. He died of a stroke after a fall in the street, though it was said to be a fall from a barstool in the Green Dragon in Fleet Street. During his lifetime were published his The Art of Thomas Hardy (1894), Poems (1895), Ireland and Other Poems (1897). He was one of the Rhymers’ Club, and cousin to Olivia Shakespear (who dedicated her novel The False Laurel to him). In June 1891, Johnson converted to Catholicism, at the same time as he introduced his cousin Lord Alfred Douglas to his friend Oscar Wilde, whom he then repudiated, directing a sonnet at him called “The Destroyer of a Soul” (1892). In 1893, Johnson wrote what some consider his masterpiece, “The Dark Angel”. “The Dark Angel” also served as one of the influences for the Dark Angels chapter of Space Marines in the Warhammer 40,000 fictional universe. Their Primarch, Lion El’Jonson, is also named after the poet. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lionel_Johnson

My name is Layla. I'm a 20 year old college student studying literature and criminal justice. I've been writing sine I was very young and have always enjoyed it and I enjoy sharing my writing with everyone who is willing enough to read and give me feedback or have any comments on my writing.

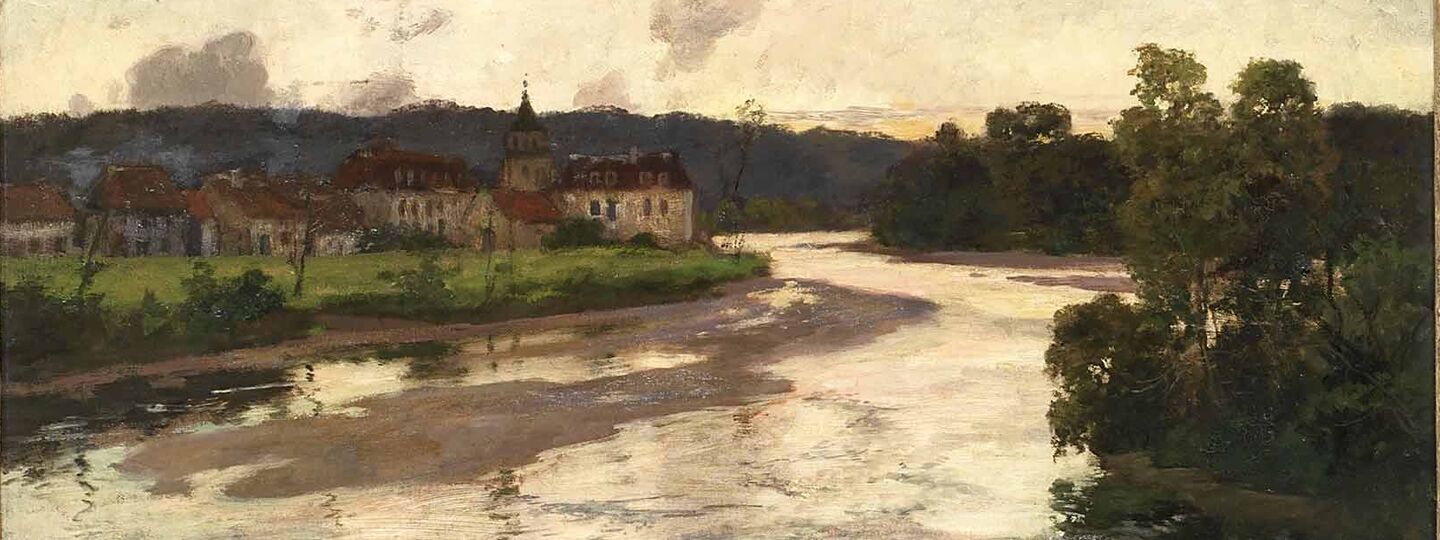

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Henry Clay Work (October 1, 1832– June 8, 1884) was an American composer and songwriter. Early life and education Work was born in Middletown, Connecticut, to Alanson and Amelia (Forbes) Work. His father opposed slavery, and Work was himself an active abolitionist and Union supporter. His family’s home became a stop on the Underground Railroad, assisting runaway slaves to freedom in Canada, for which his father was once imprisoned. Work was self-taught in music. By the time he was 23, he worked as a printer in Chicago, specializing in setting musical type. He allegedly composed in his head as he worked, without a piano, using the noise of the machinery as an inspiration. His first published song was “We Are Coming, Sister Mary”, which eventually became a staple in Christy’s Minstrels shows. Career Work produced much of his best material during the Civil War. In 1862 he published “Kingdom Coming” using his own lyrics based upon snippets of Negro speech he had heard. This use of slave dialect (Irish too was a favourite) tended to limit the appeal of Work’s works and make them frowned upon today. However, “Kingdom Coming” appeared in the Jerome Kern show “Good Morning, Dearie” on Broadway in 1921, and was heard in the background in the 1944 Judy Garland film “Meet Me in St. Louis”. 1862 also saw his novelty song “Grafted Into the Army”, followed in 1863 by “Babylon is Fallen” ("Don’t you see the black clouds risin’ ober yonder"), “The Song of a Thousand Years”, and “God Save the Nation”. His 1864 effort “Wake Nicodemus” was popular in minstrel shows. In 1865 he wrote his greatest hit, “Marching Through Georgia”, inspired by Sherman’s march to the sea at the end of the previous year. Thanks to its lively melody, the song was immensely popular, its million sheet-music sales being unprecedented. It is a cheerful marching song and has since been pressed into service many times, including by Princeton University as a football fight song. Timothy Shay Arthur’s play Ten Nights in a Barroom, had Work’s 1864 “Come Home, Father”, a dirgesome song bemoaning the demon drink: too mawkish for modern tastes, but always sung at Temperance Meetings. Settling into sentimental balladry, Work had significant post-Civil War success with the “The Lost Letter”, and “The Ship That Never Returned”—a tune reused in the "Wreck of the Old 97" and “MTA”. A massive hit was “My Grandfather’s Clock”, published in 1876, which was introduced by Sam Lucas in Hartford, Connecticut, and again secured more than a million sales of the sheet music, along with popularizing the phrase “grandfather clock” to describe a longcase clock.” By 1880 Work was living in New York City, giving his occupation as a musician. He died in Hartford two years later at the age of 51. He was survived by his wife, Sarah Parker Work, and one of their four children. Henry Clay Work was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970. He was a distant cousin to Frances Work, a great-grandmother of Diana, Princess of Wales. Songs Among the best-known of Henry Clay Work’s 75 compositions are: “Kingdom Coming” (c. 1863) “Come Home, Father” (1864) “Wake Nicodemus” (1864) “Marching Through Georgia” (1865) “The Ship That Never Returned” (1868) “Crossing the Grand Sierras” (1870) “My Grandfather’s Clock” (1876) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Clay_Work

Born on July 21, 1899, in Garrettsville, Ohio, Harold Hart Crane was a highly anxious and volatile child. He began writing verse in his early teenage years, and though he never attended college, read regularly on his own, digesting the works of the Elizabethan dramatists and poets—Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Donne—and the nineteenth-century French poets—Vildrac, Laforgue, and Rimbaud. His father, a candy manufacturer, attempted to dissuade him from a career in poetry, but Crane was determined to follow his passion to write. Living in New York City, he associated with many important figures in literature of the time, including Allen Tate, Katherine Anne Porter, E. E. Cummings, and Jean Toomer, but his heavy drinking and chronic instability frustrated any attempts at lasting friendship. An admirer of T. S. Eliot, Crane combined the influences of European literature and traditional versification with a particularly American sensibility derived from Walt Whitman. His major work, the book-length poem, The Bridge, expresses in ecstatic terms a vision of the historical and spiritual significance of America. Like Eliot, Crane used the landscape of the modern, industrialized city to create a powerful new symbolic literature. Hart Crane committed suicide in 1932, at the age of thirty-three, by jumping from the deck of a steamship sailing back to New York from Mexico. A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Poetry The Complete Poems and Selected Letters and Prose (1966) The Bridge (1930) White Buildings (1926) Prose Letters (1952) References Poets.org – http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/233

Throughout the years, the reasoning behind my writing has changed. Maybe it was a broken heart, a bad experience, falling in love or out of touch, finding myself, getting lost, escaping the crazy world we live in. Whatever the reason, writing is my solace. It’s the one place I can be completely at one with myself, where I am harmonious and comfortable with the ugly truths being human. I aim to paint the minds of others the way my experiences have painted mine, and hopefully share in my words the feelings I so deeply feel immersed in. Welcome to my world.

Kenneth Adolf Slessor OBE (27 March 1901– 30 June 1971) was an Australian poet, journalist and official War Correspondent in World War II. He was one of Australia’s leading poets, notable particularly for the absorption of modernist influences into Australian poetry. The Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry is named after him. Early life Slessor was born Kenneth Adolphe Schloesser in Orange, New South Wales. As a boy, he lived in England for a time with his parents and in Australia visited the mines of rural New South Wales with his father, a Jewish mining engineer whose father and grandfather had been distinguished musicians in Germany. His family moved to Sydney in 1903. Slessor attended Mowbray House School (1910–1914) and the Sydney Church of England Grammar School (1915–1918), where he began to write poetry. His first published poem was in 1917 about a digger in Europe, remembering Sydney and its icons. Slessor passed the 1918 NSW Leaving Certificate with first-class honours in English and joined the Sydney Sun as a journalist. In 1919, seven of his poems were published. He married for the first time in 1922. Career Slessor made his living as a newspaper journalist, mostly for the Sydney Sun, and was a war correspondent during World War II (1939–1945). Slessor counted Norman Lindsay, Hugh McCrae and Jack Lindsay among his friends. As the Australian Official War Correspondent during World War II, Slessor reported not only from Australia but from Greece, Syria, Libya, Egypt, and New Guinea. Slessor also wrote on rugby league football for the popular publication Smith’s Weekly. Poetry The bulk of Slessor’s poetic work was produced before the end of the Second World War. His poem “Five Bells”—relating to Sydney Harbour, time, the past, memory, and the death of the artist, friend and colleague of Slessor at Smith’s Weekly, Joe Lynch—remains probably his best known poem, followed by “Beach Burial”, a tribute to Australian troops who fought in World War II. In 1965, Australian writer Hal Porter wrote of having met and stayed with Slessor in the 1930s. He described Slessor as: ...a city lover, fastidious and excessively courteous, in those qualities resembles Baudelaire, as he does in being incapable of sentimentalizing over vegetation, in finding in nature something cruel, something bordering on effrontery. He prefers chiselled stone to the disorganization of grass. Awards In the New Year’s Honours of 1959, Slessor was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to literature. Personal life At the age of 21, Slessor married 28-year-old Noëla Glasson in Ashfield, Sydney, on 18 August 1922. Noëla died of cancer on 22 October 1945. He married Pauline Wallace in 1951; and a year later celebrated the birth of his only child, Paul Slessor, before the marriage dissolved in 1961. Death He died alone and suddenly of a heart attack on 30 June 1971 at the Mater Misericordiae Hospital, North Sydney. Bibliography Poetry collections * Thief of the Moon, Sydney: Hand press of J. T. Kirtley (1924) * Earth-Visitors, London: Fanfrolico Press (1926) * Trio: a book of poems, with Harley Matthews and Colin Simpson, Sydney: Sunnybrook Press (1931) * Cuckooz Contrey, Sydney: Frank Johnson (1932) * Darlinghurst Nights: and Morning glories: being 47 strange sights, Sydney (1933) * Funny Farmyard: Nursery Rhymes and Painting Book, with drawings by Sydney Miller, Sydney: Frank Johnson (1933) * Five Bells: XX Poems, Sydney: F.C. Johnson (1939) * One Hundred Poems, 1919–1939, Sydney: Angus & Robertson (1944) * “Beach Burial” 1944 * “The Night Ride” * “Sleep” * “Out of Time” 1930 Essays/prose * Bread and Wine, Sydney, Angus & Robertson (1970) Edited * Australian Poetry (1945) * The Penguin Book of Modern Australian Verse (Melbourne, 1961) Recognition Slessor has a street in the Canberra suburb of McKellar named after him. The bells motif in “Five Bells” is referenced at the end of the 1999 song “You Gotta Love This City” by The Whitlams, which also involves a drowning death in Sydney Harbour. Slessor’s poetry was chosen to be placed on the Higher School Certificate English reading lists, and was also examined in the final English exam. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenneth_Slessor

Humble, respectful, persistent a few of the words that can be used to describe myself. Kimiko Watson, a young lady of 19 years, a teacher in training. I am a student of the Bethlehem Moravian Teachers' College as our motto says: 'Mihi Cura Futuri' which is to say 'My care if for the Future'. My grandmother is the reason why I write. She has always encourage me by telling me that I can be anything and do anything that i put my mind to. I will continue to believe that any thing that I concieve I can and will achieve.

William Allingham (19 March 1824– 18 November 1889) was an Irish poet, diarist and editor. He wrote several volumes of lyric verse, and his poem 'The Faeries’ was much anthologised; but he is better known for his posthumously published Diary, in which he records his lively encounters with Tennyson, Carlyle and other writers and artists. His wife, Helen Allingham, was a well-known water-colorist and illustrator. Biography William Allingham was born on 19 March 1824 in the little port of Ballyshannon, County Donegal, Ireland, and was the son of the manager of a local bank who was of English descent. His younger brothers and sisters were Catherine (b. 1826), John (b. 1827), Jane (b. 1829), Edward (b. 1831; who lived only a few months) and a still-born brother (b. 1833). During his childhood his parents moved twice within the town, where the boy enjoyed the country sights and gardens, learned to paint and listened to his mother’s piano-playing. When he was nine, his mother died. He obtained a post in the custom-house of his native town, and held several similar posts in Ireland and England until 1870. During this period were published his Poems (1850; which included his well-known poem, 'The Fairies’) and Day and Night Songs (1855; illustrated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and others). (Rossetti’s Letters to Allingham (1854–1870), edited by Dr. Birkbeck Hill, would be published in 1897.) Lawrence Bloomfield in Ireland, his most ambitious, though not his most successful work, a narrative poem illustrative of Irish social questions, appeared in 1864. He also edited The Ballad Book for the Golden Treasury series in 1864, and Fifty Modern Poems in 1865. In April 1870 Allingham retired from the customs service, moved to London and became sub-editor of Fraser’s Magazine, eventually becoming editor in succession to James Froude in June 1874– a post he would hold till 1879. On 22 August 1874 he married the illustrator, Helen Paterson, who was twenty-four years younger than he. His wife gave up her work as an illustrator and would become well known under her married name as a water-colour painter. At first the couple lived in London, at 12 Trafalgar Square, Chelsea, near Allingham’s friend, Thomas Carlyle, and it was there that they had their first two children– Gerald Carlyle (b. 1875 November) and Eva Margaret (b. 1877 February). In 1877 appeared Allingham’s Songs, Poems and Ballads. In 1881, after the death of Carlyle, the Allinghams moved to Sandhills near Witley in Surrey, where their third child, Henry William, was born in 1882. At this period Allingham published Evil May Day (1883), Blackberries (1884) and Irish Songs and Poems (1887). In 1888, because of William’s declining health, they moved back to the capital, to the heights of Hampstead village. But in 1889, on 18 November, William died at Hampstead. According to his wishes he was cremated. His ashes are interred at St. Anne’s church in his native Ballyshannon. Posthumously Allingham’s Varieties in Prose was published in 1893. William Allingham A Diary, edited by Mrs Helen Allingham and D. Radford, was published in 1907. It contains Allingham’s reminiscences of Alfred Tennyson, Thomas Carlyle and other writers and artists. Assessment and influence Working on an un-ostentatious scale, Allingham produced much lyrical and descriptive poetry, and the best of his pieces are thoroughly national in spirit and local colouring. His verse is clear, fresh, and graceful. His best-known poem remains his early work, “The Faeries”. Allingham had a substantial influence on W. B. Yeats; while the Ulster poet John Hewitt felt Allingham’s impact keenly, and attempted to revive his reputation by editing, and writing an introduction to, The Poems of William Allingham (Oxford University Press/ Dolmen Press, 1967). Allingham’s wide-ranging anthology of poetry, Nightingale Valley (1862) was to be the inspiration for the 1923 collection Come Hither by Walter de la Mare. We daren’t go a-hunting/For fear of little men... was quoted by the character of The Tinker near the beginning of the movie Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, as well as in Mike Mignola’s comic book short story Hellboy: The Corpse, plus the 1973 horror film Don’t Look in the Basement. Several lines of the poem are quoted by Henry Flyte, a character in issue No. 65 of the Supergirl comic book, August 2011. This same poem was quoted in Andre Norton’s 1990 science fiction novel Dare To Go A-Hunting (ISBN 0-812-54712-8). Up the Airy Mountain is the title of a short story by Debra Doyle and James D. Macdonald; while the working title of Terry Pratchett’s The Wee Free Men was “For Fear of Little Men”. The Allingham Arms Hotel in Bundoran, Co. Donegal is named after him. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Allingham

I have always used poetry as a means to express my highest thoughts and deepest feelings down on paper. Now, I hope they can inspire you, to perhaps do the same, and look inward. For a more in-depth look into my work, click the link to my debut novel. https://www.philosophypsychologyprinciplespractice.com/ Also, check out my Pinterest page for more inspirational content: https://www.pinterest.com.au/SigmaSocrates/_created/

Harriet Monroe (December 23, 1860– September 26, 1936) was an American editor, scholar, literary critic, poet and patron of the arts. She is best known as the founding publisher and long-time editor of Poetry magazine, which made its debut in 1912. As a supporter of the poets Wallace Stevens, Ezra Pound, H. D., T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Carl Sandburg, Max Michelson and others, she played an important role in the development of modern poetry. Because she was a longtime correspondent of the poets she supported, her letters provide a wealth of information on their thoughts and motives. Monroe was born in Chicago, Illinois. She read at an early age; her father had a large library that provided refuge from domestic discord. In her autobiography, A Poet’s Life: Seventy Years in a Changing World, published two years after her death, Monroe recalls: “I started in early with Shakespeare, Byron, Shelley, with Dickens and Thackeray; and always the book-lined library gave me a friendly assurance of companionship with lively and interesting people, gave me friends of the spirit to ease my loneliness.”