Info

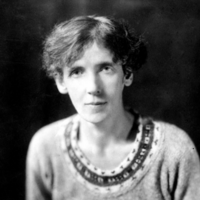

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin (October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018) was an American novelist. She worked mainly in the genres of fantasy and science fiction. She also authored children’s books, short stories, poetry, and essays. Her writing was first published in the 1960s and often depicted futuristic or imaginary alternative worlds in politics, the natural environment, gender, religion, sexuality, and ethnography. In 2016, The New York Times described her as “America’s greatest living science fiction writer”, although she said that she would prefer to be known as an “American novelist”. She influenced Booker Prize winners and other writers, such as Salman Rushdie and David Mitchell, and science fiction and fantasy writers including Neil Gaiman and Iain Banks. She won the Hugo Award, Nebula Award, Locus Award, and World Fantasy Award, each more than once. In 2014, she was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. In 2003, she was made a Grandmaster of Science Fiction, one of a few women writers to take the top honor in the genre. Life Birth and family Ursula Kroeber was the daughter of anthropologist Alfred Louis Kroeber of the University of California, Berkeley, and writer Theodora Kracaw. Childhood and education Ursula and her three older brothers, Clifton, Theodore, and Karl Kroeber, were encouraged to read and were exposed to their parents’ dynamic friend group, which included Native Americans and Robert Oppenheimer, who was later to become in part a model for her hero in The Dispossessed. Le Guin stated that, in retrospect, she was grateful for the ease and happiness of her upbringing. The encouraging environment fostered Le Guin’s interest in literature; her first fantasy story was written at age 9, her first science fiction story submitted for publication in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction at age 11. The family spent the academic year in Berkeley, retreating in the summers to “Kishamish” in Napa Valley, "an old, tumble-down ranch... [and] a gathering place for scientists, writers, students, and California Indians. Even though I didn’t pay much attention, I heard a lot of interesting, grown-up conversation." She was interested in biology and poetry, but found math difficult. Le Guin attended Berkeley High School. She received her B.A. (Phi Beta Kappa) in Renaissance French and Italian literature from Radcliffe College in 1951, and M.A. in French and Italian literature from Columbia University in 1952. Soon after, Le Guin began her Ph.D. work and won a Fulbright grant to continue her studies in France from 1953 to 1954. Marriage and family In 1953, while traveling to France aboard the Queen Mary, Le Guin met her future husband, historian Charles Le Guin. They married later that year in Paris. After marrying, Le Guin chose not to continue her doctoral studies of the poet Jean Lemaire de Belges. The couple returned to the United States so that he could pursue his Ph.D. at Emory University. During this time, she worked as a secretary and taught French at the university level. Their first child, Elisabeth (1957), was born in Moscow, Idaho, where Charles taught. In 1958 the Le Guins moved to Portland, Oregon, where their daughter Caroline (1959) was born, and where they lived thereafter. Charles is Emeritus Professor of History at Portland State University. During this time, she continued to make time for writing in addition to maintaining her family life. In 1964, her third child, Theodore, was born. Death Le Guin died on January 22, 2018, at her home in Portland, Oregon; her son stated that she had been in poor health for several months. Her New York Times obituary called her “the immensely popular author who brought literary depth and a tough-minded feminist sensibility to science fiction and fantasy with books like The Left Hand of Darkness and the Earthsea series”. Writing career Le Guin became interested in literature quite early. At age 11, she submitted her first story to the magazine Astounding Science Fiction. Despite being rejected, she continued writing but did not attempt to publish for the next ten years. From 1951 to 1961 she wrote five novels, which publishers rejected, because they seemed inaccessible. She also wrote poetry during this time, including Wild Angels (1975). Her earliest writings, some of which she adapted in Orsinian Tales and Malafrena, were non-fantastic stories set in the imaginary country of Orsinia. Searching for a way to express her interests, she returned to her early interest in science fiction; in the early 1960s her work began to be published regularly. One Orsinian Tale was published in the Summer 1961 issue of The Western Humanities Review and three of her stories appeared in 1962 and 1963 numbers of Fantastic Stories of Imagination, a monthly edited by Cele Goldsmith. Goldsmith also edited Amazing Stories, which ran two of Le Guin’s stories in 1964, including the first “Hainish” story. In 1964 the short story “The Word of Unbinding” was published. This was the first of the Earthsea fantasy series, which includes six books and eight short stories. The three linked young adult novels beginning with A Wizard of Earthsea (1968), The Tombs of Atuan (1970), and The Farthest Shore (1972), sometimes referred to as The Earthsea Trilogy, in later years would be joined by the books Tehanu, Tales from Earthsea and The Other Wind. Le Guin received wide recognition for her novel The Left Hand of Darkness, which won the Hugo and Nebula awards in 1970. Her subsequent novel The Dispossessed made her the first person to win both the Hugo and Nebula Awards for Best Novel twice for the same two books. In later years, Le Guin worked in film and audio. She contributed to The Lathe of Heaven, a 1979 PBS film based on her novel of the same name. In 1985 she collaborated with avant-garde composer David Bedford on the libretto of Rigel 9, a space opera. In May 1983 she delivered a well-received commencement address entitled “A Left-Handed Commencement Address” at Mills College, Oakland, California. “A Left-Handed Commencement Address” is included in her nonfiction collection Dancing at the Edge of the World. In 1984, Le Guin was part of a group along with Ken Kesey, Brian Booth, and William Stafford that founded the Oregon Institute of Literary Arts, which is now known as Literary Arts in Portland. In December 2009, Le Guin resigned from the Authors Guild in protest over its endorsement of Google Books, Google’s book digitization project. “You decided to deal with the devil”, she wrote in her resignation letter. “There are principles involved, above all the whole concept of copyright; and these you have seen fit to abandon to a corporation, on their terms, without a struggle.” (See Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google, Inc..) Influences Le Guin was influenced by fantasy writers, including J. R. R. Tolkien, by science fiction writers, including Philip K. Dick (who was in her high school class, though they did not know each other), by central figures of Western literature such as Leo Tolstoy, Virgil and the Brontë sisters, by feminist writers such as Virginia Woolf, by children’s literature such as Alice in Wonderland, The Wind in the Willows, The Jungle Book, by Norse mythology, and by books from the Eastern tradition such as the Tao Te Ching. When asked about her influences, she replied: Once I learned to read, I read everything. I read all the famous fantasies – Alice in Wonderland, and Wind in the Willows, and Kipling. I adored Kipling’s Jungle Book. And then when I got older I found Lord Dunsany. He opened up a whole new world – the world of pure fantasy. And... Worm Ouroboros. Again, pure fantasy. Very, very fattening. And then my brother and I blundered into science fiction when I was 11 or 12. Early Asimov, things like that. But that didn’t have too much effect on me. It wasn’t until I came back to science fiction and discovered Sturgeon – but particularly Cordwainer Smith.... I read the story “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard”, and it just made me go, “Wow! This stuff is so beautiful, and so strange, and I want to do something like that.” In the mid-1950s, she read J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, which had an enormous impact on her. But rather than making her want to follow in Tolkien’s footsteps, it simply showed her what was possible with the fantasy genre. Themes Le Guin exploits the creative flexibility of the science fiction and fantasy genres to undertake thorough explorations of dimensions of both social and psychological identity and of broader cultural and social structures. In doing so, she draws on sociology, anthropology, and psychology, leading some critics to categorize her work as soft science fiction. She objected to this classification of her writing, arguing the term is divisive and implies a narrow view of what constitutes valid science fiction. Underlying ideas of anarchism and environmentalism also make repeated appearances throughout Le Guin’s work. In 2014 Le Guin said about the appeal of contemplating possible futures in science fiction: anything at all can be said to happen [in the future] without fear of contradiction from a native. The future is a safe, sterile laboratory for trying out ideas in, a means of thinking about reality, a method. Sociology, anthropology and psychology Being so thoroughly informed by social science perspectives on identity and society, Le Guin treats race and gender quite deliberately. The majority of her main characters are people of color, a choice made to reflect the non-white majority of humans, and one to which she attributes the frequent lack of character illustrations on her book covers. Her writing often makes use of alien (i.e., human but non-Terran) cultures to examine structural characteristics of human culture and society and their impact on the individual. This prominent theme of cultural interaction is most likely rooted in the fact that Le Guin grew up in a household of anthropologists where she was surrounded by the remarkable case of Ishi – a Native American acclaimed in his time as the “last wild Indian” – and his interaction with the white man’s world. Le Guin’s father was director of the University of California Museum of Anthropology, where Ishi was studied and worked as a research assistant. Her mother wrote the bestseller Ishi in Two Worlds. Similar elements are echoed through many of Le Guin’s stories – from Planet of Exile and City of Illusions to The Word for World Is Forest and The Dispossessed. Le Guin’s writing notably employs the ordinary actions and transactions of everyday life, clarifying how these daily activities embed individuals in a context of relation to the physical world and to one another. For example, the engagement of the main characters with the everyday business of looking after animals, tending gardens and doing domestic chores is central to the novel Tehanu. Themes of Jungian psychology also are prominent in her writing. For example Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle, a series of novels encompassing a loose collection of societies, of various related human species, that exist largely in isolation from one another, providing the setting for her explorations of intercultural encounter. The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed and The Telling all consider the consequences of contact between different worlds and cultures. Unlike those in much mainstream science fiction, Hainish Cycle civilization does not possess reliable human faster-than-light travel, but does have technology for instantaneous communication. The social and cultural impact of the arrival of Ekumen envoys (known as “mobiles”) on remote planets, and the culture shock that the envoys experience, constitute major themes of The Left Hand of Darkness. Le Guin’s concept has been borrowed explicitly by several other well-known authors, to the extent of using the name of the communication device (the “ansible”). The Left Hand of Darkness is particularly noted for the way she explores social, cultural, and personal consequences of sexual identity through a novel involving a human’s encounter with an intermittently androgynous race. In addition to androgyny, Le Guin’s focus on sexuality breaks down normative gender roles. “Solitude”, one of the stories in The Birthday of the World: and Other Stories follows a young girl, more adventurous and daring than her older brother, into a world dominated by strong, territorial women. In Paradises Lost, the people of a spaceship several generations into the voyage to a new colony-world are saved by a female interstellar navigator, an archetypal role typically reserved for men. Environmentalism Elizabeth McDowell states in her 1992 master’s thesis that Le Guin "identif[ies] the present dominant socio-political American system as problematic and destructive to the health and life of the natural world, humanity, and their interrelations". This idea recurs in several of Le Guin’s works, most notably The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), The Word for World Is Forest (1972), The Dispossessed (1974), The Eye of the Heron (1978), Always Coming Home (1985), and “Buffalo Gals, Won’t You Come Out Tonight” (1987). All of these works center on ideas regarding socio-political organization and value-system experiments in both utopias and dystopias. As McDowell explains, “Although many of Le Guin’s works are exercises in the fantastic imagination, they are equally exercises of the political imagination.” In addition to her fiction, Le Guin’s book Out Here: Poems and Images from Steens Mountain Country, a collaboration with artist Roger Dorband, is a clear environmental testament to the natural beauty of that area of Eastern Oregon. Le Guin also wrote several works of poetry and nonfiction on Mount St. Helens following the 1980 eruption. These works explore local stories and discussions surrounding the eruption event in conjunction with Le Guin’s own perspective as it relates to viewing the eruption and mountain from her home in Portland, as well as her various visits into the blast zone. Anarchism and Taoism Le Guin’s feelings towards anarchism were closely tied to her Taoist beliefs and both ideas appear in her work. “Taoism and Anarchism fit together in some very interesting ways and I’ve been a Taoist ever since I learned what it was.” She participated in numerous peace marches and although she did not call herself an anarchist, since she did not live the lifestyle, she did feel that “Democracy is good but it isn’t the only way to achieve justice and a fair share.” Le Guin said: “The Dispossessed is an Anarchist utopian novel. Its ideas come from the Pacifist Anarchist tradition – Kropotkin etc. So did some of the ideas of the so-called counterculture of the sixties and seventies.” She also said that anarchism “is a necessary ideal at the very least. It is an ideal without which we couldn’t go on. If you are asking me is anarchism at this point a practical movement, well, then you get in the question of where you try to do it and who’s living on your boundary?” Le Guin has been credited with helping to popularize anarchism as her work "rescues anarchism from the cultural ghetto to which it has been consigned [and] introduces the anarchist vision... into the mainstream of intellectual discourse". Indeed her works were influential in developing a new anarchist way of thinking; a postmodern way that is more adaptable and looks at/addresses a broader range of concerns. Adaptations of her work Few of Le Guin’s major works have been adapted for film or television. Her 1971 novel The Lathe of Heaven has been adapted twice: The first adaptation was made in 1979 by WNET Channel 13 in New York, with her own participation, and the second adaptation was made in 2002 by the A&E Network. In a 2008 interview, she said she considers the 1979 adaptation as “the only good adaptation to film” of her work to date. In the early 1980s animator and director Hayao Miyazaki asked permission to create an animated adaptation of Earthsea. However, Le Guin, who was unfamiliar with his work and anime in general, turned down the offer. Years later, after seeing My Neighbor Totoro, she reconsidered her refusal, believing that if anyone should be allowed to direct an Earthsea film, it should be Hayao Miyazaki. The third and fourth Earthsea books were used as the basis of the 2006 animated film Tales from Earthsea (ゲド戦記, Gedo Senki). The film, however, was directed by Miyazaki’s son, Gorō, rather than Hayao Miyazaki himself, which disappointed Le Guin. While she was positive about the aesthetic of the film, writing that “much of it was beautiful”, she took great issue with its re-imagining of the moral sense of the books and greater focus on physical violence. "[E]vil has been comfortably externalized in a villain", Le Guin writes, "the wizard Kumo/Cob, who can simply be killed, thus solving all problems. In modern fantasy (literary or governmental), killing people is the usual solution to the so-called war between good and evil. My books are not conceived in terms of such a war, and offer no simple answers to simplistic questions.” In 1987, the CBC Radio anthology program Vanishing Point adapted The Dispossessed into a series of six 30-minute episodes, and at an unspecified date The Word for World Is Forest as a series of three 30-minute episodes. In 1995, Chicago’s Lifeline Theatre presented its adaptation of The Left Hand of Darkness. Reviewer Jack Helbig at the Chicago Reader wrote that the “adaptation is intelligent and well crafted but ultimately unsatisfying”, in large measure because it is extremely difficult to compress a complex 300-page novel into a two-hour stage presentation. In 2004 the Sci Fi Channel adapted the first two books of the Earthsea trilogy as the miniseries Legend of Earthsea. Le Guin was highly critical of the adaptation, calling it a “far cry from the Earthsea I envisioned”, objecting both to the use of white actors for her red, brown, or black-skinned characters, and to the way she was “cut out of the process”. Her novella, Paradises Lost, published in The Birthday of the World: and Other Stories, was adapted into an opera by the American composer Stephen Andrew Taylor and Canadian librettist Marcia Johnson. The opera premiered April 26, 2012 at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts on the campus of the University of Illinois. In 2013, the Portland Playhouse and Hand2Mouth Theatre produced a stage adaptation of The Left Hand of Darkness, directed and adapted by Jonathan Walters, with text adapted by John Schmor. The play opened May 2, 2013, and ran until June 16, 2013, in Portland, Oregon. In 2015, the BBC commissioned radio adaptations of The Left Hand of Darkness and the first three Earthsea novels. The Left Hand of Darkness was aired as two hour-long episodes, and Earthsea as six half-hour episodes. In early 2017 Le Guin’s award winning novel The Left Hand of Darkness was picked up by Critical Content, a production company formerly known as Relativity Television, to be produced as a television limited series. Le Guin was to serve as a consulting producer on the project.

William Sydney Graham (19 November 1918– 9 January 1986) was a Scottish poet who is often associated with Dylan Thomas and the neo-romantic group of poets. Graham’s poetry was mostly overlooked in his lifetime but, partly due to the support of Harold Pinter, his work has enjoyed a revival in recent years. He was represented in the second edition of the Penguin Book of Contemporary Verse (Harmondsworth, UK, 1962) and the Anthology of Twentieth-Century British and Irish Poetry (Oxford University Press, 2001). Early life and work Graham was born in Greenock. In 1932, he left school to become an apprentice draughtsman and then studied structural engineering at Stow College, Glasgow. He was awarded a bursary to study literature for a year at Newbattle Abbey College in 1938. Graham spent the war years working at a number of jobs in Scotland and Ireland before moving to Cornwall in 1944. His first book, Cage Without Grievance was published in 1942. Graham and the neo-romantics The 1940s were prolific years for Graham, and he published four more books during that decade. These were The Seven Journeys (1944)' 2ND Poems (1945), The Voyages of Alfred Wallis (1948) and The White Threshold (1949). The style of these early poems led critics to see Graham as part of the neo-romantic group that included Dylan Thomas and George Barker. The affinities between these three poets derive from a common interest in poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins, Arthur Rimbaud and Hart Crane, and, in the cases of Thomas and Graham, a taste for the Bohemian lifestyle of the London literary scene. In 1947, Graham received the Atlantic Award for Literature, and lectured at New York University whilst spending a year on a reading touring of the United States. He moved to London to be nearer the hub of that Bohemian world. Here he came into contact with T. S. Eliot, then editor of Faber and Faber who published The White Threshold and who were to remain Graham’s publishers for the rest of his life. The Nightfishing and legacy In 1954, Graham returned to Cornwall to live near the St. Ives artists colony. Here he became friendly with several of the resident painters, including Bryan Wynter and Roger Hilton. The following year, Faber and Faber published his The Nightfishing, a book whose title poem marked a dramatic change in Graham’s poetry. The poem moved on from his earlier style and moved away from the neo-romantic/apocalyptic tag. Unfortunately for the poet, the poem’s appearance coincided with the rise of the Movement with their open hostility to the neo-romantics, and, despite the support of Eliot and Hugh MacDiarmid, the book was neither a critical nor a popular success. It was to be fifteen years before Graham published another book, Malcolm Mooney’s Land (1970). This, and his last book, “Implements In Their Places” are truly original and enduring poetic achievements, for which Graham is slowly coming to be recognised. For many years, he had been living in semi-poverty on his income as a writer, but in 1974 he received a Civil List pension of £500 per year. Perhaps because of this alleviation of his financial circumstances, Graham began to publish with more frequency, with Implements in their Places (1977), Collected Poems 1942–1977 (1979) and an American-published Selected Poems (1980). He died in Madron, Cornwall in 1986. His last collection Aimed at Nobody was published posthumously in 1993 and a book of Uncollected Poems appeared in 1990. Faber brought out a new Selected Poems in 1996. The Nightfisherman: Selected Letters was published in 1999 and New Collected Poems in 2005. All Graham’s poems have a location, a plot and setting (or narrative) as Graham insisted ‘the first act of engagement of reader and poem was in reading it aloud. This tested the syntax, pace and tone of poem and reader ’. Posthumous publication activity indicates, Graham’s reputation has grown in recent years. Some might argue this is partly due to Harold Pinter’s often-expressed enthusiasm for the poet, or attribute his increasing recognition to the widespread advocacy of poets associated with the British Poetry Revival. However Graham’s work was represented in the anthology Conductors of Chaos (1996) by a selection introduced by the poet and critic Tony Lopez, who also wrote a book-length study, The Poetry of W. S. Graham (1989). Marriage, death and recognition He married another poet, Agnes Kilpatrick Dunsmuir (1909–1999), known as “Nessie Dunsmuir”. He died on 9 January 1986. Copyright in Graham’s works is held by his daughter, Rosalind Mudaliar. In 2006, 20 years after his death, memorial plaques were unveiled in Fore Street, Madron where he spent his final years, and at his birthplace, 1 Hope Street, Greenock. Bibliography * Cage without Grievance, Parton Press, 1942 * The Seven Journeys, William MacLellan, 1944 * 2ND Poems, Nicholson and Watson, 1945 * The White Threshold, Faber and Faber, 1949 * The Nightfishing, Faber and Faber, 1955 * Malcolm Mooney’s Land, Faber and Faber, 1970 * Penguin Modern Poets 17, David Gascoyne, W. S. Graham, Kathleen Raine, Penguin Books, 1970 * Implements in their Places, Faber and Faber, 1977 * Collected Poems, 1942-1977, Faber and Faber, 1979 * Selected Poems, Ecco Press, 1980 * Uncollected Poems, Greville Press, 1990 * Aimed at Nobody: Poems from Notebooks, ed. Margaret Blackwood and Robin Skelton, Faber and Faber, 1993 * Selected Poems, Faber and Faber, 1996 * W.S. Graham Selected by Nessie Dunsmuir, Greville Press, 1998 * The Night Fisherman: Selected Letters of W. S. Graham, ed. Michael and Margaret Snow, Carcanet, 1999 * New Collected Poems, ed. Matthew Francis, Faber and Faber, 2004 * Approaches to How They Behave, Donut Press, 2009 * Les Dialogues obscurs / The Dark Dialogues, selected poems, bilingual book English-French, introduction Michael Snow, afterword Paul Stubbs, Black Herald Press, 2013 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._S._Graham

Basil Cheesman Bunting (1 March 1900– 17 April 1985) was a significant British modernist poet whose reputation was established with the publication of Briggflatts in 1966. He had a lifelong interest in music that led him to emphasise the sonic qualities of poetry, particularly the importance of reading poetry aloud. He was an accomplished reader of his own work. Life and career Born into a Quaker family in Scotswood-on-Tyne, Northumberland, he studied at two Quaker schools: from 1912 to 1916 at Ackworth School in the West Riding of Yorkshire and from 1916 to 1918 at Leighton Park School in Berkshire. His Quaker education strongly influenced his pacifist opposition to the First World War, and in 1918 he was arrested as a conscientious objector having been refused recognition by the tribunals and refusing to comply with a notice of call-up. Handed over to the military, he was court-martialled for refusing to obey orders, and served a sentence of more than a year in Wormwood Scrubs and Winchester prisons. Bunting’s friend Louis Zukofsky described him as a "conservative/anti-fascist/imperialist", though Bunting himself listed the major influences on his artistic and personal outlook somewhat differently as “Jails and the sea, Quaker mysticism and socialist politics, a lasting unlucky passion, the slums of Lambeth and Hoxton ...” These events were to have an important role in his first major poem, “Villon” (1925). “Villon” was one of a rather rare set of complex structured poems that Bunting labelled “sonatas,” thus underlining the sonic qualities of his verse and recalling his love of music. Other “sonatas” include “Attis: or, Something Missing,” “Aus Dem Zweiten Reich,” “The Well of Lycopolis,” “The Spoils” and, finally, “Briggflatts.” After his release from prison in 1919, traumatised by the time spent there, Bunting went to London, where he enrolled in the London School of Economics, and had his first contacts with journalists, social activists and Bohemia. Bunting was introduced to the works of Ezra Pound by Nina Hamnett who lent him a copy of Homage to Sextus Propertius. The glamour of the cosmopolitan modernist examples of Nina Hamnett and Mina Loy seems to have influenced Bunting in his later move from London to Paris. After travelling in Northern Europe, Bunting left the London School of Economics without a degree and went to France. There, in 1923, he became friendly with Ezra Pound, who years later would dedicate his Guide to Kulchur (1938) to both Bunting and Louis Zukofsky, “strugglers in the desert”. Between February and October 1927, Bunting wrote articles and reviews for The Outlook, and then became its music critic until the magazine ceased publication in 1928. Bunting’s poetry began to show the influence of the friendship with Pound, whom he visited in Rapallo, Italy, and later settled there with his family from 1931 to 1933. He was published in the Objectivist issue of Poetry magazine, in the Objectivist Anthology, and in Pound’s Active Anthology. During the Second World War, Bunting served in British Military Intelligence in Persia. After the war, in 1948, he left government service to become the correspondent for The Times of London, in Iran. He married an Iranian woman– Sima Alladian– whilst continuing his intelligence work with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company Tehran, until he was expelled by Mohammad Mossadegh in 1952. Back in Newcastle, he worked as a journalist on the Evening Chronicle until his rediscovery during the 1960s by young poets, notably Tom Pickard and Jonathan Williams, who were interested in working in the modernist tradition. In 1965, he published his major long poem, Briggflatts, named after the Quaker village in Cumbria where he is now buried. In later life he published Advice to Young Poets, beginning "I SUGGEST / 1. Compose aloud; poetry is a sound.” Bunting died in 1985 in Hexham, Northumberland. The Basil Bunting Poetry Award and Young Person’s Prize, administered by Newcastle University, are open internationally to any poet writing in English. Briggflatts Divided into five parts, Briggflatts is an autobiographical long poem, looking back on teenage love and on Bunting’s involvement in the high modernist period. In addition, Briggflatts can be read as a meditation on the limits of life and a celebration of Northumbrian culture and dialect, as symbolised by events and figures like the doomed Viking King Eric Bloodaxe. The critic Cyril Connolly was among the first to recognise the poem’s value, describing it as “the finest long poem to have been published in England since T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets”. Portrait bust of Basil Bunting Basil Bunting sat in Northumberland for sculptor Alan Thornhill, with a resulting terracotta (for bronze) in existence. The correspondence file relating to the Bunting portrait bust is held as part of the Thornhill Papers (2006:56) in the archive of the Henry Moore Foundation’s Henry Moore Institute in Leeds and the terracotta remains in the collection of the artist. The 1973 portrait is displayed in the Burton (2014) biography of Bunting. In popular culture Mark Knopfler wrote a song, titled 'Basil’, about his time as a Saturday afternoon copy boy on the Newcastle Evening Chronicle when Bunting worked there. The song was recorded for Knopfler’s 2015 album Tracker. Books * 1930: Redimiculum Matellarum (privately printed) * 1950: Poems (Cleaners’ Press, 1950) revised and published as Loquitur (Fulcrum Press, 1965). * 1951: The Spoils * 1965: First Book of Odes * 1965: Ode II/2 * 1966: Briggflatts: An Autobiography * 1967: Two Poems * 1967: What the Chairman Told Tom * 1968: Collected Poems * 1972: Version of Horace * 1991: Uncollected Poems (posthumous, edited by Richard Caddel) * 1994: The Complete Poems (posthumous, edited by Richard Caddel) * 1999: Basil Bunting on Poetry (posthumous, edited by Peter Makin) * 2000: Complete Poems (posthumous, edited by Richard Caddel) * 2009: Briggflatts (with audio CD and video DVD) * 2012: Bunting’s Persia (Translations by Basil Bunting. Edited by Don Share) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basil_Bunting

George Frederick Cameron (24 September 1854– 17 September 1885) was a Canadian poet, lawyer, and journalist, best known for the libretto for the operetta Leo, the Royal Cadet. He moved to Boston in April 1869. He graduated from the Boston University School of Law in 1877. He worked for the law firm Dean, Butler and Abbot of Boston from 1877 to 1882. He contributed poetry to Boston periodicals, including the Courier and the Transcript. In fall 1882 he enrolled in Queen’s College in Kingston, Ontario where he won a poetry prize in 1883 for “Adelphi.” He is sometimes considered one of the Confederation Poets.

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban, PC KC (/ˈbeɪkən/; 22 January 1561– 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, jurist, orator, and author. He served both as Attorney General and as Lord Chancellor of England. After his death, he remained extremely influential through his works, especially as philosophical advocate and practitioner of the scientific method during the scientific revolution. Bacon has been called the father of empiricism. His works argued for the possibility of scientific knowledge based only upon inductive and careful observation of events in nature. Most importantly, he argued this could be achieved by use of a skeptical and methodical approach whereby scientists aim to avoid misleading themselves. While his own practical ideas about such a method, the Baconian method, did not have a long lasting influence, the general idea of the importance and possibility of a skeptical methodology makes Bacon the father of scientific method. This marked a new turn in the rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, the practical details of which are still central in debates about science and methodology today. Bacon was generally neglected at court by Queen Elizabeth, but after the accession of King James I in 1603, Bacon was knighted. He was later created Baron Verulam in 1618 and Viscount St. Alban in 1621. Because he had no heirs, both titles became extinct upon his death in 1626, at 65 years of age. Bacon died of pneumonia, with one account by John Aubrey stating that he had contracted the condition while studying the effects of freezing on the preservation of meat. Biography Early life Francis Bacon was born on 22 January 1561 at York House near the Strand in London, the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon by his second wife, Anne (Cooke) Bacon, the daughter of the noted humanist Anthony Cooke. His mother’s sister was married to William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, making Burghley Bacon’s uncle. Biographers believe that Bacon was educated at home in his early years owing to poor health, which would plague him throughout his life. He received tuition from John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning toward Puritanism. He entered Trinity College, Cambridge, on 5 April 1573 at the age of 12, living for three years there, together with his older brother Anthony Bacon under the personal tutelage of Dr John Whitgift, future Archbishop of Canterbury. Bacon’s education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. He was also educated at the University of Poitiers. It was at Cambridge that he first met Queen Elizabeth, who was impressed by his precocious intellect, and was accustomed to calling him “The young lord keeper”. His studies brought him to the belief that the methods and results of science as then practised were erroneous. His reverence for Aristotle conflicted with his rejection of Aristotelian philosophy, which seemed to him barren, disputatious and wrong in its objectives. On 27 June 1576, he and Anthony entered de societate magistrorum at Gray’s Inn. A few months later, Francis went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador at Paris, while Anthony continued his studies at home. The state of government and society in France under Henry III afforded him valuable political instruction. For the next three years he visited Blois, Poitiers, Tours, Italy, and Spain. During his travels, Bacon studied language, statecraft, and civil law while performing routine diplomatic tasks. On at least one occasion he delivered diplomatic letters to England for Walsingham, Burghley, and Leicester, as well as for the queen. The sudden death of his father in February 1579 prompted Bacon to return to England. Sir Nicholas had laid up a considerable sum of money to purchase an estate for his youngest son, but he died before doing so, and Francis was left with only a fifth of that money. Having borrowed money, Bacon got into debt. To support himself, he took up his residence in law at Gray’s Inn in 1579, his income being supplemented by a grant from his mother Lady Anne of the manor of Marks near Romford in Essex, which generated a rent of £46. Parliamentarian Bacon stated that he had three goals: to uncover truth, to serve his country, and to serve his church. He sought to further these ends by seeking a prestigious post. In 1580, through his uncle, Lord Burghley, he applied for a post at court that might enable him to pursue a life of learning, but his application failed. For two years he worked quietly at Gray’s Inn, until he was admitted as an outer barrister in 1582. His parliamentary career began when he was elected MP for Bossiney, Cornwall, in a by-election (similar to a special election in the US) in 1581. In 1584 he took his seat in parliament for Melcombe in Dorset, and in 1586 for Taunton. At this time, he began to write on the condition of parties in the church, as well as on the topic of philosophical reform in the lost tract Temporis Partus Maximus. Yet he failed to gain a position that he thought would lead him to success. He showed signs of sympathy to Puritanism, attending the sermons of the Puritan chaplain of Gray’s Inn and accompanying his mother to the Temple Church to hear Walter Travers. This led to the publication of his earliest surviving tract, which criticised the English church’s suppression of the Puritan clergy. In the Parliament of 1586, he openly urged execution for the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots. About this time, he again approached his powerful uncle for help; this move was followed by his rapid progress at the bar. He became a bencher in 1586 and was elected a Reader in 1587, delivering his first set of lectures in Lent the following year. In 1589, he received the valuable appointment of reversion to the Clerkship of the Star Chamber, although he did not formally take office until 1608; the post was worth £1,600 a year. In 1588 he became MP for Liverpool and then for Middlesex in 1593. He later sat three times for Ipswich (1597, 1601, 1604) and once for Cambridge University (1614). He became known as a liberal-minded reformer, eager to amend and simplify the law. Though a friend of the crown, he opposed feudal privileges and dictatorial powers. He spoke against religious persecution. He struck at the House of Lords in its usurpation of the Money Bills. He advocated for the union of England and Scotland, which made him a significant influence toward the consolidation of the United Kingdom; and he later would advocate for the integration of Ireland into the Union. Closer constitutional ties, he believed, would bring greater peace and strength to these countries. Attorney General Bacon soon became acquainted with Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, Queen Elizabeth’s favourite. By 1591 he acted as the earl’s confidential adviser. In 1592 he was commissioned to write a tract in response to the Jesuit Robert Parson’s anti-government polemic, which he titled Certain observations made upon a libel, identifying England with the ideals of democratic Athens against the belligerence of Spain. Bacon took his third parliamentary seat for Middlesex when in February 1593 Elizabeth summoned Parliament to investigate a Roman Catholic plot against her. Bacon’s opposition to a bill that would levy triple subsidies in half the usual time offended the Queen: opponents accused him of seeking popularity, and for a time the Court excluded him from favour. When the office of Attorney General fell vacant in 1594, Lord Essex’s influence was not enough to secure the position for Bacon and it was given to Sir Edward Coke. Likewise, Bacon failed to secure the lesser office of Solicitor General in 1595, the Queen pointedly snubbing him by appointing Sir Thomas Fleming instead. To console him for these disappointments, Essex presented him with a property at Twickenham, which Bacon subsequently sold for £1,800. In 1596 Bacon became Queen’s Counsel, but missed the appointment of Master of the Rolls. During the next few years, his financial situation remained embarrassing. His friends could find no public office for him, and a scheme for retrieving his position by a marriage with the wealthy and young widow Lady Elizabeth Hatton failed after she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to Sir Edward Coke, a further spark of enmity between the men. In 1598 Bacon was arrested for debt. Afterward, however, his standing in the Queen’s eyes improved. Gradually, Bacon earned the standing of one of the learned counsels, though he had no commission or warrant, and received no salary. His relationship with the Queen further improved when he severed ties with Essex—a shrewd move, as Essex would be executed for treason in 1601. With others, Bacon was appointed to investigate the charges against Essex. A number of Essex’s followers confessed that Essex had planned a rebellion against the Queen. Bacon was subsequently a part of the legal team headed by the Attorney General Sir Edward Coke at Essex’s treason trial. After the execution, the Queen ordered Bacon to write the official government account of the trial, which was later published as A DECLARATION of the Practices and Treasons attempted and committed by Robert late Earle of Essex and his Complices, against her Majestie and her Kingdoms... after Bacon’s first draft was heavily edited by the Queen and her ministers. According to his personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, as a judge Bacon was always tender-hearted, “looking upon the examples with the eye of severity, but upon the person with the eye of pity and compassion”. And also that “he was free from malice”, “no revenger of injuries”, and “no defamer of any man”. James I comes to the throne The succession of James I brought Bacon into greater favour. He was knighted in 1603. In another shrewd move, Bacon wrote his Apologies in defence of his proceedings in the case of Essex, as Essex had favoured James to succeed to the throne. The following year, during the course of the uneventful first parliament session, Bacon married Alice Barnham. In June 1607 he was at last rewarded with the office of solicitor general. The following year, he began working as the Clerkship of the Star Chamber. Despite a generous income, old debts still could not be paid. He sought further promotion and wealth by supporting King James and his arbitrary policies. In 1610 the fourth session of James’s first parliament met. Despite Bacon’s advice to him, James and the Commons found themselves at odds over royal prerogatives and the king’s embarrassing extravagance. The House was finally dissolved in February 1611. Throughout this period Bacon managed to stay in the favour of the king while retaining the confidence of the Commons. In 1613 Bacon was finally appointed attorney general, after advising the king to shuffle judicial appointments. As attorney general, Bacon, by his zealous efforts—which included torture—to obtain the conviction of Edmund Peacham for treason, raised legal controversies of high constitutional importance; and successfully prosecuted Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset, and his wife, Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, for murder in 1616. The so-called Prince’s Parliament of April 1614 objected to Bacon’s presence in the seat for Cambridge and to the various royal plans that Bacon had supported. Although he was allowed to stay, parliament passed a law that forbade the attorney general to sit in parliament. His influence over the king had evidently inspired resentment or apprehension in many of his peers. Bacon, however, continued to receive the King’s favour, which led to his appointment in March 1617 as temporary Regent of England (for a period of a month), and in 1618 as Lord Chancellor. On 12 July 1618 the king created Bacon Baron Verulam, of Verulam, in the Peerage of England; he then became known as Francis, Lord Verulam. Bacon continued to use his influence with the king to mediate between the throne and Parliament, and in this capacity he was further elevated in the same peerage, as Viscount St Alban, on 27 January 1621. Lord Chancellor and public disgrace Bacon’s public career ended in disgrace in 1621. After he fell into debt, a parliamentary committee on the administration of the law charged him with 23 separate counts of corruption. His lifelong enemy, Sir Edward Coke, who had instigated these accusations, was one of those appointed to prepare the charges against the chancellor. To the lords, who sent a committee to enquire whether a confession was really his, he replied, “My lords, it is my act, my hand, and my heart; I beseech your lordships to be merciful to a broken reed.” He was sentenced to a fine of £40,000 and committed to the Tower of London at the king’s pleasure; the imprisonment lasted only a few days and the fine was remitted by the king. More seriously, parliament declared Bacon incapable of holding future office or sitting in parliament. He narrowly escaped undergoing degradation, which would have stripped him of his titles of nobility. Subsequently, the disgraced viscount devoted himself to study and writing. There seems little doubt that Bacon had accepted gifts from litigants, but this was an accepted custom of the time and not necessarily evidence of deeply corrupt behaviour. While acknowledging that his conduct had been lax, he countered that he had never allowed gifts to influence his judgement and, indeed, he had on occasion given a verdict against those who had paid him. He even had an interview with King James in which he assured: The law of nature teaches me to speak in my own defence: With respect to this charge of bribery I am as innocent as any man born on St. Innocents Day. I never had a bribe or reward in my eye or thought when pronouncing judgment or order... I am ready to make an oblation of myself to the King He also wrote the following to Buckingham: My mind is calm, for my fortune is not my felicity. I know I have clean hands and a clean heart, and I hope a clean house for friends or servants; but Job himself, or whoever was the justest judge, by such hunting for matters against him as hath been used against me, may for a time seem foul, especially in a time when greatness is the mark and accusation is the game. The true reason for his acknowledgement of guilt is the subject of debate, but some authors speculate that it may have been prompted by his sickness, or by a view that through his fame and the greatness of his office he would be spared harsh punishment. He may even have been blackmailed, with a threat to charge him with sodomy, into confession. The British jurist Basil Montagu wrote in Bacon’s defence, concerning the episode of his public disgrace: Bacon has been accused of servility, of dissimulation, of various base motives, and their filthy brood of base actions, all unworthy of his high birth, and incompatible with his great wisdom, and the estimation in which he was held by the noblest spirits of the age. It is true that there were men in his own time, and will be men in all times, who are better pleased to count spots in the sun than to rejoice in its glorious brightness. Such men have openly libelled him, like Dewes and Weldon, whose falsehoods were detected as soon as uttered, or have fastened upon certain ceremonious compliments and dedications, the fashion of his day, as a sample of his servility, passing over his noble letters to the Queen, his lofty contempt for the Lord Keeper Puckering, his open dealing with Sir Robert Cecil, and with others, who, powerful when he was nothing, might have blighted his opening fortunes for ever, forgetting his advocacy of the rights of the people in the face of the court, and the true and honest counsels, always given by him, in times of great difficulty, both to Elizabeth and her successor. When was a “base sycophant” loved and honoured by piety such as that of Herbert, Tennison, and Rawley, by noble spirits like Hobbes, Ben Jonson, and Selden, or followed to the grave, and beyond it, with devoted affection such as that of Sir Thomas Meautys. Personal life When he was 36, Bacon courted Elizabeth Hatton, a young widow of 20. Reportedly, she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to a wealthier man, Bacon’s rival, Edward Coke. Years later, Bacon still wrote of his regret that the marriage to Hatton had not taken place. At the age of 45, Bacon married Alice Barnham, the 14-year-old daughter of a well-connected London alderman and MP. Bacon wrote two sonnets proclaiming his love for Alice. The first was written during his courtship and the second on his wedding day, 10 May 1606. When Bacon was appointed lord chancellor, “by special Warrant of the King”, Lady Bacon was given precedence over all other Court ladies. Reports of increasing friction in his marriage to Alice appeared, with speculation that some of this may have been due to financial resources not being as readily available to her as she had been accustomed to. Alice was reportedly interested in fame and fortune, and when reserves of money were no longer available there were complaints about where all the money was going. Alice Chambers Bunten wrote in her Life of Alice Barnham that, upon their descent into debt, she actually went on trips to ask for financial favours and assistance from their circle of friends. Bacon disinherited her upon discovering her secret romantic relationship with Sir John Underhill. He rewrote his will, which had previously been very generous—leaving her lands, goods, and income—revoking it all. Bacon’s personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, however, wrote in his biography of Bacon that his marriage was one of “much conjugal love and respect”, mentioning a robe of honour that he gave to Alice and which “she wore unto her dying day, being twenty years and more after his death”. The well-connected antiquary John Aubrey noted in his Brief Lives concerning Bacon, “He was a Pederast. His Ganimeds and Favourites tooke Bribes”, biographers continue to debate Bacon’s sexual inclinations and the precise nature of his personal relationships. Some authors believe that despite his marriage, Bacon was primarily attracted to men. Forker, for example, has explored the “historically documentable sexual preferences” of both King James and Bacon, and concluded they were all oriented to “masculine love”, a contemporary term that “seems to have been used exclusively to refer to the sexual preference of men for members of their own gender.” The Jacobean antiquarian Sir Simonds D’Ewes implied there had been a question of bringing him to trial for buggery, which his brother Anthony Bacon had also been charged with. This conclusion has been disputed by others, who point to lack of consistent evidence, and consider the sources to be more open to interpretation. In his “New Atlantis”, Bacon describes his utopian island as being “the chastest nation under heaven”, in which there was no prostitution or adultery, and further saying that “as for masculine love, they have no touch of it”. Death On 9 April 1626, Bacon died of pneumonia while at Arundel mansion at Highgate outside London. An influential account of the circumstances of his death was given by John Aubrey’s Brief Lives, with Aubrey stating he contracted pneumonia while studying the effects of freezing on the preservation of meat. Aubrey has been criticised for his evident credulousness in this and other works; on the other hand, he knew Thomas Hobbes, Bacon’s fellow-philosopher and friend. Aubrey’s vivid account, which portrays Bacon as a martyr to experimental scientific method, had him journeying to Highgate through the snow with the King’s physician when he is suddenly inspired by the possibility of using the snow to preserve meat: “They were resolved they would try the experiment presently. They alighted out of the coach and went into a poor woman’s house at the bottom of Highgate hill, and bought a fowl, and made the woman exenterate it.” After stuffing the fowl with snow, Bacon contracted a fatal case of pneumonia. Some people, including Aubrey, consider these two contiguous, possibly coincidental events as related and causative of his death: "The Snow so chilled him that he immediately fell so extremely ill, that he could not return to his Lodging... but went to the Earle of Arundel’s house at Highgate, where they put him into... a damp bed that had not been layn-in... which gave him such a cold that in 2 or 3 days as I remember Mr Hobbes told me, he died of Suffocation.” Being unwittingly on his deathbed, the philosopher wrote his last letter to his absent host and friend Lord Arundel: My very good Lord,—I was likely to have had the fortune of Caius Plinius the elder, who lost his life by trying an experiment about the burning of Mount Vesuvius; for I was also desirous to try an experiment or two touching the conservation and induration of bodies. As for the experiment itself, it succeeded excellently well; but in the journey between London and Highgate, I was taken with such a fit of casting as I know not whether it were the Stone, or some surfeit or cold, or indeed a touch of them all three. But when I came to your Lordship’s House, I was not able to go back, and therefore was forced to take up my lodging here, where your housekeeper is very careful and diligent about me, which I assure myself your Lordship will not only pardon towards him, but think the better of him for it. For indeed your Lordship’s House was happy to me, and I kiss your noble hands for the welcome which I am sure you give me to it. I know how unfit it is for me to write with any other hand than mine own, but by my troth my fingers are so disjointed with sickness that I cannot steadily hold a pen. Another account appears in a biography by William Rawley, Bacon’s personal secretary and chaplain: He died on the ninth day of April in the year 1626, in the early morning of the day then celebrated for our Saviour’s resurrection, in the sixty-sixth year of his age, at the Earl of Arundel’s house in Highgate, near London, to which place he casually repaired about a week before; God so ordaining that he should die there of a gentle fever, accidentally accompanied with a great cold, whereby the defluxion of rheum fell so plentifully upon his breast, that he died by suffocation. At the news of his death, over 30 great minds collected together their eulogies of him, which were then later published in Latin. He left personal assets of about £7,000 and lands that realised £6,000 when sold. His debts amounted to more than £23,000, equivalent to more than £3m at current value. Philosophy and works Francis Bacon’s philosophy is displayed in the vast and varied writings he left, which might be divided into three great branches: Scientific works– in which his ideas for an universal reform of knowledge into scientific methodology and the improvement of mankind’s state using the Scientific method are presented. Religious and literary works– in which he presents his moral philosophy and theological meditations. Juridical works– in which his reforms in English Law are proposed. Influence Science Bacon’s seminal work Novum Organum was influential in the 1630s and 1650s among scholars, in particular Sir Thomas Browne, who in his encyclopaedia Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646–72) frequently adheres to a Baconian approach to his scientific enquiries. During the Restoration, Bacon was commonly invoked as a guiding spirit of the Royal Society founded under Charles II in 1660. During the 18th-century French Enlightenment, Bacon’s non-metaphysical approach to science became more influential than the dualism of his French contemporary Descartes, and was associated with criticism of the ancien regime. In 1733 Voltaire introduced him to a French audience as the “father” of the scientific method, an understanding which had become widespread by the 1750s. In the 19th century his emphasis on induction was revived and developed by William Whewell, among others. He has been reputed as the “Father of Experimental Philosophy”. He also wrote a long treatise on Medicine, History of Life and Death, with natural and experimental observations for the prolongation of life. One of his biographers, the historian William Hepworth Dixon, states: “Bacon’s influence in the modern world is so great that every man who rides in a train, sends a telegram, follows a steam plough, sits in an easy chair, crosses the channel or the Atlantic, eats a good dinner, enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation, owes him something.” In 1902 Hugo von Hofmannsthal published a fictional letter addressed to Bacon and dated 1603, about a writer who is experiencing a crisis of language. Known as The Lord Chandos Letter, it has been proposed that Bacon was identified as its recipient as having laid the foundation for the work of scientists such as Ernst Mach, notable both for his academic distinction in the history and philosophy of the inductive sciences, and for his own contributions to physics. North America Bacon played a leading role in establishing the British colonies in North America, especially in Virginia, the Carolinas and Newfoundland in northeastern Canada. His government report on “The Virginia Colony” was submitted in 1609. In 1610 Bacon and his associates received a charter from the king to form the Tresurer and the Companye of Adventurers and planter of the Cittye of London and Bristoll for the Collonye or plantacon in Newfoundland, and sent John Guy to found a colony there. Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, wrote: “Bacon, Locke and Newton. I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences”. In 1910 Newfoundland issued a postage stamp to commemorate Bacon’s role in establishing the colony. The stamp describes Bacon as "the guiding spirit in Colonization Schemes in 1610". Moreover, some scholars believe he was largely responsible for the drafting, in 1609 and 1612, of two charters of government for the Virginia Colony. William Hepworth Dixon considered that Bacon’s name could be included in the list of Founders of the United States. Law Although few of his proposals for law reform were adopted during his lifetime, his legal legacy was considered by the magazine New Scientist in 1961 as having influenced the drafting of the Napoleonic Code as well as the law reforms introduced by 19th-century British Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel. The historian William Hepworth Dixon had referred to the Napoleonic Code as “the sole embodiment of Bacon’s thought”, saying that Bacon’s legal work “has had more success abroad than it has found at home”, and that in France “it has blossomed and come into fruit”. Harvey Wheeler attributed to Bacon, in Francis Bacon’s Verulamium—the Common Law Template of The Modern in English Science and Culture, the creation of these distinguishing features of the modern common law system: using cases as repositories of evidence about the “unwritten law”; determining the relevance of precedents by exclusionary principles of evidence and logic; treating opposing legal briefs as adversarial hypotheses about the application of the “unwritten law” to a new set of facts. As late as the 18th century some juries still declared the law rather than the facts, but already before the end of the 17th century Sir Matthew Hale explained modern common law adjudication procedure and acknowledged Bacon as the inventor of the process of discovering unwritten laws from the evidences of their applications. The method combined empiricism and inductivism in a new way that was to imprint its signature on many of the distinctive features of modern English society. Paul H. Kocher writes that Bacon is considered by some jurists to be the father of modern Jurisprudence. Bacon is commemorated with a statue in Gray’s Inn, South Square in London where he received his legal training, and where he was elected Treasurer of the Inn in 1608. James McClellan, a political scientist from the University of Virginia, considered Bacon to have had “a great following” in the American colonies. More recent scholarship on Bacon’s jurisprudence has focused on his advocating torture as a legal recourse for the crown. Bacon himself was not a stranger to the torture chamber: in his various legal capacities in both Elizabeth I’s and James I’s reigns, Bacon was listed as a commissioner on five torture warrants. In 1613(?), in a letter addressed to King James I on the question of torture’s place within English law, Bacon identifies the scope of torture: a means to further the investigation of threats to the state: “In the cases of treasons, torture is used for discovery, and not for evidence.” For Bacon, torture was not a punitive measure, an intended form of state repression, but instead offered a modus operandi for the government agent tasked with uncovering acts of treason. Historical debates Bacon and Shakespeare The Baconian hypothesis of Shakespearean authorship, first proposed in the mid-19th century, contends that Francis Bacon wrote some or even all of the plays conventionally attributed to William Shakespeare. Occult hypotheses Francis Bacon often gathered with the men at Gray’s Inn to discuss politics and philosophy, and to try out various theatrical scenes that he admitted writing. Bacon’s alleged connection to the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons has been widely discussed by authors and scholars in many books. However, others, including Daphne du Maurier in her biography of Bacon, have argued that there is no substantive evidence to support claims of involvement with the Rosicrucians. Frances Yates does not make the claim that Bacon was a Rosicrucian, but presents evidence that he was nevertheless involved in some of the more closed intellectual movements of his day. She argues that Bacon’s movement for the advancement of learning was closely connected with the German Rosicrucian movement, while Bacon’s New Atlantis portrays a land ruled by Rosicrucians. He apparently saw his own movement for the advancement of learning to be in conformity with Rosicrucian ideals. The link between Bacon’s work and the Rosicrucians ideals which Yates allegedly found was the conformity of the purposes expressed by the Rosicrucian Manifestos and Bacon’s plan of a “Great Instauration”, for the two were calling for a reformation of both “divine and human understanding”, as well as both had in view the purpose of mankind’s return to the “state before the Fall”. Another major link is said to be the resemblance between Bacon’s New Atlantis and the German Rosicrucian Johann Valentin Andreae’s Description of the Republic of Christianopolis (1619). Andreae describes a utopic island in which Christian theosophy and applied science ruled, and in which the spiritual fulfillment and intellectual activity constituted the primary goals of each individual, the scientific pursuits being the highest intellectual calling—linked to the achievement of spiritual perfection. Andreae’s island also depicts a great advancement in technology, with many industries separated in different zones which supplied the population’s needs—which shows great resemblance to Bacon’s scientific methods and purposes. The Rosicrucian organisation AMORC claims that Bacon was the “Imperator” (leader) of the Rosicrucian Order in both England and the European continent, and would have directed it during his lifetime. Bacon’s influence can also be seen on a variety of religious and spiritual authors, and on groups that have utilised his writings in their own belief systems. Bibliography * Some of the more notable works by Bacon are: * Essays (1st edition 1597) * The Advancement and Proficience of Learning Divine and Human (1605) * Essays (2nd edition– 38 essays, 1612) * Novum Organum Scientiarum ('New Method’, 1620) * Essays, or Counsels Civil and Moral (3rd/final edition– 58 essays, 1625) * New Atlantis (1627) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon

John Yau (born 1950) is an American poet and critic who lives in New York City. He received his B.A. from Bard College in 1972 and his M.F.A. from Brooklyn College in 1978. He has published over 50 books of poetry, artists' books, fiction, and art criticism. According to Matthew Rohrer's profile on Yau from Poets & Writers Magazine, Yau's parents settled in Boston after emigrating from China in 1949. His father was a bookkeeper. Yau characterizes his father as an outsider - "My father was half English and half Chinese [...] so he never fit in." As a child Yau was friends with the son of the Chinese-born abstract painter John Way. By the late 1960s Yau was exposed to, "a lot of anti-war poetry readings in Boston [and] so I'd heard Robert Bly, Denise Levertov, Galway Kinnell, people like that. I don't know - Robert Kelly (poet) just seemed a different kind of poet. Mysterious, in a way. He was interested in the occult, in gnosticism and abstract art - things that had a particular appeal to me." According to Rohrer, Yau's decision to attend Bard College was motivated by his admiration of Kelly. Yau's most recent books are Exhibits (Letter Machine Editions, 2010), A Thing Among Things: The Art of Jasper Johns (Distributed Art Publishers, 2009), and The Passionate Spectator: Essays on Art and Poetry (University of Michigan Press, 2006). His collections of poetry include Paradiso Diaspora (Penguin, 2006), Ing Grish, with Paintings by Thomas Nozkowski (Saturnalia, 2005),Borrowed Love Poems (Penguin, 2002), Forbidden Entries (Black Sparrow, 1996), Berlin Diptychon with Photographs by Bill Barrette (Timken, 1995), Edificio Sayonara (Black Sparrow, 1992),Corpse and Mirror (Holt & Rinehardt, 1983), a National Poetry Series book selected by John Ashbery, and Broken Off by The Music (Burning Deck, 1981). Artists' books include projects with Squeak Carnwath, Richard Tuttle, Norbert Prangenberg, Hanns Schimannsky, Archie Rand, Norman Bluhm, Pat Steir, Suzanne McClelland, Robert Therrien, Leiko Ikemura, and Jürgen Partenheimer (a.o.), his books of art criticism include The United States of Jasper Johns (1996) and In the Realm of Appearances: The Art of Andy Warhol (1993). He has also edited Fetish (1998), a fiction anthology. Yau has been the Arts editor of The Brooklyn Rail since March 2004. He also runs a small press, Black Square Editions, which publishes translations, poetry, and fiction. Yau currently teaches art criticism at Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University. Awards Yau has received awards and grants from Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation, the Academy of American Poets (Lavan Award), The American Poetry Review (Jerome Shestack Award), the Ingram Merrill Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the General Electric Foundation, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. Bibliography * 1983 – Corpse and Mirror (Poems) * 1989 – Radiant Silhouette: Selected Writing 1974-1988 (Poems and prose) * 1992 – Edificio Sayonara (Poems) * 1993 – In the Realm of Appearances: The Art of Andy Warhol (Critique) * 1995 – Berlin Diptychon (Poems) * 1995 – Hawaiian Cowboys (Short stories) * 1996 – Forbidden Entries (Poems) * 1996 – The United States of Jasper Johns (Critique) * 1998 – Fetish (Editor) * 1998 – My Symptoms (Short Stories) * 1999 – In Company: Robert Creeley's Collaborations (Essay) * 2002 – Borrowed Love Poems (Poems) * 2005 - Ing Grish * 2006 - Paradiso Diaspora * 2006 – "andalusia" Authors: John Yau (Poems), Leiko Ikemura, Verlag: Weidle Verlag, ISBN 3-931135-96-9 * 2008 - A Thing Among Things: The Art of Jasper Johns, Distributed Art Publishers, ISBN 1933045620 * 2010 - Exhibits (Poem) * 2012 - Further Adventures in Monochrome (Copper Canyon Press) (Poetry) References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Yau

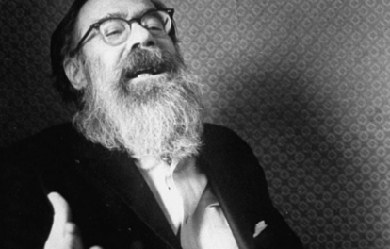

Carl Rakosi (November 6, 1903– June 25, 2004) was the last surviving member of the original group of poets who were given the rubric Objectivist. He was still publishing and performing his poetry well into his 90s. Early life Rakosi was born in Berlin and lived there and in Hungary until 1910, when he moved to the United States to live with his father and stepmother. His father was a jeweler and watchmaker in Chicago and later in Gary, Indiana. The family lived in semi-poverty but contrived to send him to the University of Chicago and then to the University of Wisconsin–Madison. During his time studying at the university level, he started writing poetry. On graduating, he worked for a time as a social worker, then returned to college to study psychology. At this time, he changed his name to Callman Rawley because he felt he stood a better chance of being employed if he had a more American-sounding name. After a spell as a psychologist and teacher, he returned to social work for the rest of his working life. Early writings At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Rakosi edited the Wisconsin Literary Magazine. His own poetry at this stage was influenced by W. B. Yeats, Wallace Stevens, and E. E. Cummings. He also started reading William Carlos Williams and T. S. Eliot. By 1925, he was publishing poems in The Little Review and Nation. Pound and the Objectivists By the late 1920s, Rakosi was in correspondence with Ezra Pound, who prompted Louis Zukofsky to contact him. This led to Rakosi’s inclusion in the Objectivist issue of Poetry and in the Objectivist Anthology. Rakosi himself had reservations about the Objectivist tag, feeling that the poets involved were too different from each other to form a group in any meaningful sense of the word. He did, however, especially admire the work of Charles Reznikoff. Later career Like a number of his fellow Objectivists, Rakosi abandoned poetry in the 1940s. After his 1941 Selected Poems he dedicated himself to social work and apparently neither read nor wrote poetry. Years earlier, shortly after his twenty-first birthday, Rakosi had legally changed his name to Callman Rawley, believing that he would not find work with his foreign-sounding name. Under his adopted name, he served as head of the Minneapolis Jewish Children’s and Family Service from 1945 until his retirement in 1968. A letter from the English poet Andrew Crozier about his early poetry was the trigger that started Rakosi writing again. His first book in 26 years, Amulet, was published by New Directions in 1967 and his Collected Poems in 1986 by the National Poetry Foundation. These were followed by several more volumes and by readings across the United States and Europe. In early November 2003, Rakosi celebrated his 100th birthday with friends at the San Francisco Public Library. Upon his death Jacket Magazine editor John Tranter observed the following: Poet Carl Rakosi died on Friday afternoon June 25 at the age of 100, after a series of strokes, in his home in San Francisco. My wife Lyn and I were passing through California in November 2003, and we stopped by to have a coffee with Carl at his home in Sunset. By a lucky coincidence, it happened to be his 100th birthday. He was, as always, kind, thoughtful, bright and alert, and as sharp as a pin. We felt privileged to know him. External links Rakosi at Modern American Poetry The Carl Rakosi Papers in the Mandeville Special Collections Library at UC San Diego Carl Rakosi Reading and Interview on KPFA’s Ode To Gravity, 13 May 1971 (from The Internet Archive) Obituary in The Guardian, UK Carl Rakosi feature at Jacket Magazine includes Rakosi in conversation with Tom Devaney & Olivier Brossard; link to audio recordings at University of Pennsylvania, and poems, dedications & remembrances from Jane Augustine, Robert Creeley, Laurie Duggan, Michael Heller and Kent Johnson “Add-Verse” a poetry-photo-video project Rakosi participated in References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Rakosi

Helen Joy Davidman (18 April 1915 – 13 July 1960) was an American poet and writer. Often referred to as a child prodigy, she earned a master's degree from Columbia University in English literature at age twenty in 1935. For her book of poems, Letter to a Comrade, she won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition in 1938 and the Russell Loines Award for Poetry in 1939. She was the author of several books, including two novels.

Maryann Corbett (née Zillotti, Washington, D.C.) is an American poet, medievalist, and linguist.She grew up in northern Virginia. She did her undergraduate work at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, and graduated with a doctorate in English from the University of Minnesota.Her work has appeared in Southwest Review, Barrow Street, Rattle, River Styx, Atlanta Review, The Evansville Review, Measure, Literary Imagination, The Dark Horse, Italian Americana, Mezzo Cammin, Linebreak, Subtropics, Verse Daily, American Life in Poetry, The Poetry Foundation, The Writer’s Almanac, and many other venues in print and online, as well as an assortment of anthologies, including The Best American Poetry 2018. She has been a several-time Pushcart and Best of the Net nominee; a finalist for the 2009 Morton Marr Prize, the 2010 Best of the Net anthology, and the 2011 and 2016 Able Muse Book Prize; and a winner of the Lyric Memorial Award, the Willis Barnstone Translation Prize, and the Richard Wilbur Award. Her third book, Mid Evil, is the Wilbur Award winner and has been published by the University of Evansville Press.She has worked as a writing teacher and indexer for the Minnesota Legislature. She lives in St. Paul, Minnesota.