Pedro Salinas Serrano (Madrid, 27 de noviembre de 1891 – Boston, 4 de diciembre de 1951) fue un escritor español conocido sobre todo por su poesía y ensayos. Dentro del contexto de la Generación del 27, se le considera uno de sus mayores poetas. Sus traducciones de Proust contribuyeron al conocimiento del novelista francés en el mundo hispanohablante. Al concluir la guerra civil española, se exilió en Estados Unidos hasta su muerte.

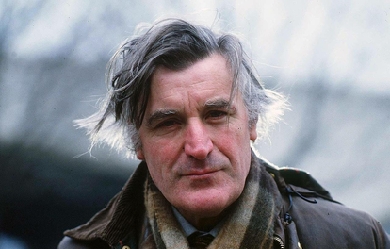

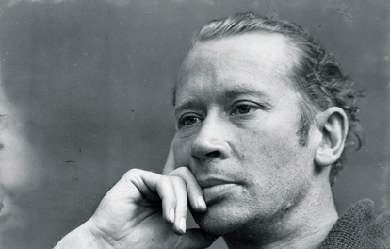

Edward James (Ted) Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding district of Yorkshire, on August 17, 1930. His childhood was quiet and dominately rural. When he was seven years old, his family moved to the small town of Mexborough in South Yorkshire, and the landscape of the moors of that area informed his poetry throughout his life. Hughes graduated from Cambridge in 1954. A few years later, in 1956, he co-founded the literary magazine St. Botolph’s Review with a handful of other editors. At the launch party for the magazine, he met Sylvia Plath. A few short months later, on June 16, 1956, they were married.

Rafael Pombo, (Bogotá, República de Nueva Granada, 7 de noviembre de 1833 – Bogotá, Colombia, 5 de mayo de 1924), fue un poeta, escritor, fabulista, traductor, intelectual y diplomático colombiano. Sus padres fueron Lino de Pombo O'Donnell y Ana María Rebolledo, ambos pertenecientes a familias de la aristocracia de Popayán. Cuando el General Francisco de Paula Santander designó a Lino de Pombo como secretario del Interior y de Relaciones Exteriores, éste aceptó y viajó desde Popayán con su familia a Bogotá. Cuando la familia llegó a Bogotá, Ana María Rebolledo tenía 9 meses de embarazo, por lo que poco después dio a luz a su primogénito José Rafael de Pombo Rebolledo.

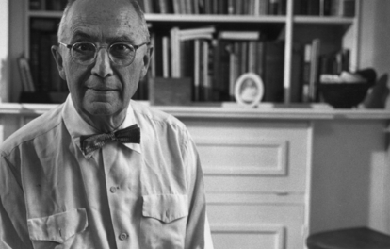

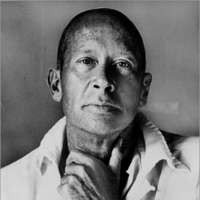

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Williams "worked harder at being a writer than he did at being a physician" but excelled at both. Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry (his main literary focus), he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays, and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night. Early in his career, he briefly became involved in the Imagist movement through his friendships with Ezra Pound and H.D. (also known as Hilda Doolittle, another well-known poet whom he befriended while attending the University of Pennsylvania), but soon he began to develop opinions that differed from those of his poet/friends.

Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson, CBE (17 February 1864– 5 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the district around Binalong, New South Wales, where he spent much of his childhood. Paterson’s more notable poems include “Waltzing Matilda”, “The Man from Snowy River” and “Clancy of the Overflow”.

James Whitcomb Riley (October 7, 1849 – July 22, 1916) was an American writer, poet, and best-selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the "Hoosier Poet" and "Children's Poet" for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man". Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and created a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform. He became more popular in spite of the bad press he received, and as a result extricated himself from poorly negotiated contracts that limited his earnings; he quickly became very wealthy. Riley became a bestselling author in the 1890s. His children's poems were compiled into a book and illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy. Titled the Rhymes of Childhood, the book was his most popular and sold millions of copies. As a poet, Riley achieved an uncommon level of fame during his own lifetime. He was honored with annual Riley Day celebrations around the United States and was regularly called on to perform readings at national civic events. He continued to write and hold occasional poetry readings until a stroke paralyzed his right arm in 1910. Riley's chief legacy was his influence in fostering the creation of a midwestern cultural identity and his contributions to the Golden Age of Indiana Literature. Along with other writers of his era, he helped create a caricature of midwesterners and formed a literary community that produced works rivaling the established eastern literati. There are many memorials dedicated to Riley, including the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children. Family and background James Whitcomb Riley was born on October 7, 1849, in the town of Greenfield, Indiana, the third of the six children of Reuben Andrew and Elizabeth Marine Riley.[n 1] Riley's father was an attorney, and in the year before Riley's birth, he was elected a member of the Indiana House of Representatives as a Democrat. He developed a friendship with James Whitcomb, the governor of Indiana, after whom he named his son. Martin Riley, Riley's uncle, was an amateur poet who occasionally wrote verses for local newspapers. Riley was fond of his uncle who helped influence his early interest in poetry. Shortly after Riley's birth, the family moved into a larger house in town. Riley was "a quiet boy, not talkative, who would often go about with one eye shut as he observed and speculated." His mother taught him to read and write at home before sending him to the local community school in 1852. He found school difficult and was frequently in trouble. Often punished, he had nothing kind to say of his teachers in his writings. His poem "The Educator" told of an intelligent but sinister teacher and may have been based on one of his instructors. Riley was most fond of his last teacher, Lee O. Harris. Harris noticed Riley's interest in poetry and reading and encouraged him to pursue it further. Riley's school attendance was sporadic, and he graduated from grade eight at age twenty in 1869. In an 1892 newspaper article, Riley confessed that he knew little of mathematics, geography, or science, and his understanding of proper grammar was poor. Later critics, like Henry Beers, pointed to his poor education as the reason for his success in writing; his prose was written in the language of common people which spurred his popularity. Childhood influences Riley lived in his parents' home until he was twenty-one years old. At five years old he began spending time at the Brandywine Creek just outside Greenfield. His poems "The Barefoot Boy" and "The Old Swimmin' Hole" referred back to his time at the creek. He was introduced in his childhood to many people who later influenced his poetry. His father regularly brought home a variety of clients and disadvantaged people to give them assistance. Riley's poem "The Raggedy Man" was based on a German tramp his father hired to work at the family home. Riley picked up the cadence and character of the dialect of central Indiana from travelers along the old National Road. Their speech greatly influenced the hundreds of poems he wrote in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect. Riley's mother frequently told him stories of fairies, trolls, and giants, and read him children's poems. She was very superstitious, and influenced Riley with many of her beliefs. They both placed "spirit rappings" in their homes on places like tables and bureaus to capture any spirits that may have been wandering about. This influence is recognized in many of his works, including "Flying Islands of the Night." As was common at that time, Riley and his friends had few toys and they amused themselves with activities. With his mother's aid, Riley began creating plays and theatricals which he and his friends would practice and perform in the back of a local grocery store. As he grew older, the boys named their troupe the Adelphians and began to have their shows in barns where they could fit larger audiences. Riley wrote of these early performances in his poem "When We First Played 'Show'," where he referred to himself as "Jamesy." Many of Riley's poems are filled with musical references. Riley had no musical education, and could not read sheet music, but learned from his father how to play guitar, and from a friend how to play violin. He performed in two different local bands, and became so proficient on the violin he was invited to play with a group of adult Freemasons at several events. A few of his later poems were set to music and song, one of the most well known being A Short'nin' Bread Song—Pieced Out. When Riley was ten years old, the first library opened in his hometown. From an early age he developed a love of literature. He and his friends spent time at the library where the librarian read stories and poems to them. Charles Dickens became one Riley's favorites, and helped inspire the poems "St. Lirriper," "Christmas Season," and "God Bless Us Every One." Riley's father enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War, leaving his wife to manage the family home. While he was away, the family took in a twelve-year-old orphan named Mary Alice "Allie" Smith. Smith was the inspiration for Riley's poem "Little Orphant Annie". Riley intended to name the poem "Little Orphant Allie", but a typesetter's error changed the name of the poem during printing. Finding poetry Riley's father returned from the war partially paralyzed. He was unable to continue working in his legal practice and the family soon fell into financial distress. The war had a negative physiological effect on him, and his relationship with his family quickly deteriorated. He opposed Riley's interest in poetry and encouraged him to find a different career. The family finances finally disintegrated and they were forced to sell their town home in April 1870 and return to their country farm. Riley's mother was able to keep peace in the family, but after her death in August from heart disease, Riley and his father had a final break. He blamed his mother's death on his father's failure to care for her in her final weeks. He continued to regret the loss of his childhood home and wrote frequently of how it was so cruelly snatched from him by the war, subsequent poverty, and his mother's death. After the events of 1870, he developed an addiction to alcohol which he struggled with for the remainder of his life. Becoming increasingly belligerent toward his father, Riley moved out of the family home and briefly had a job painting houses before leaving Greenfield in November 1870. He was recruited as a Bible salesman and began working in the nearby town of Rushville, Indiana. The job provided little income and he returned to Greenfield in March 1871 where he started an apprenticeship to a painter. He completed the study and opened a business in Greenfield creating and maintaining signs. His earliest known poems are verses he wrote as clever advertisements for his customers. Riley began participating in local theater productions with the Adelphians to earn extra income, and during the winter months, when the demand for painting declined, Riley began writing poetry which he mailed to his brother living in Indianapolis. His brother acted as his agent and offered the poems to the newspaper Indianapolis Mirror for free. His first poem was featured on March 30, 1872 under the pseudonym "Jay Whit." Riley wrote more than twenty poems to the newspaper, including one that was featured on the front page. In July 1872, after becoming convinced sales would provide more income than sign painting, he joined the McCrillus Company based in Anderson, Indiana. The company sold patent medicines that they marketed in small traveling shows around Indiana. Riley joined the act as a huckster, calling himself the "Painter Poet". He traveled with the act, composing poetry and performing at the shows. After his act he sold tonics to his audience, sometimes employing dishonesty. During one stop, Riley presented himself as a formerly blind painter who had been cured by a tonic, using himself as evidence to encourage the audience to purchase his product. Riley began sending poems to his brother again in February 1873. About the same time he and several friends began an advertisement company. The men traveled around Indiana creating large billboard-like signs on the sides of buildings and barns and in high places that would be visible from a distance. The company was financially successful, but Riley was continually drawn to poetry. In October he traveled to South Bend where he took a job at Stockford & Blowney painting verses on signs for a month; the short duration of his job may have been due to his frequent drunkenness at that time. In early 1874, Riley returned to Greenfield to become a writer full-time. In February he submitted a poem entitled "At Last" to the Danbury News, a Connecticut newspaper. The editors accepted his poem, paid him for it, and wrote him a letter encouraging him to submit more. Riley found the note and his first payment inspiring. He began submitting poems regularly to the editors, but after the newspaper shut down in 1875, Riley was left without a paying publisher. He began traveling and performing with the Adelphians around central Indiana to earn an income while he searched for a new publisher. In August 1875 he joined another traveling tonic show run by the Wizard Oil Company. Newspaper work Riley began sending correspondence to the famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during late 1875 seeking his endorsement to help him start a career as a poet. He submitted many poems to Longfellow, whom he considered to be the greatest living poet. Not receiving a prompt response, he sent similar letters to John Townsend Trowbridge, and several other prominent writers askng for an endorsement. Longfellow finally replied in a brief letter, telling Riley that "I have read [the poems] in great pleasure, and think they show a true poetic faculty and insight." Riley carried the letter with him everywhere and, hoping to receive a job offer and to create a market for his poetry, he began sending poems to dozens of newspapers touting Longfellow's endorsement. Among the newspapers to take an interest in the poems was the Indianapolis Journal, a major Republican Party metropolitan newspaper in Indiana. Among the first poems the newspaper purchased from Riley were "Song of the New Year", "An Empty Nest", and a short story entitled "A Remarkable Man". The editors of the Anderson Democrat discovered Riley's poems in the Indianapolis Journal and offered him a job as a reporter in February 1877. Riley accepted. He worked as a normal reporter gathering local news, writing articles, and assisting in setting the typecast on the printing press. He continued to write poems regularly for the newspaper and to sell other poems to larger newspapers. During the year Riley spent working in Anderson, he met and began to court Edora Mysers. The couple became engaged, but terminated the relationship after they decided against marriage in August. After a rejection of his poems by an eastern periodical, Riley began to formulate a plot to prove his work was of good quality and that it was being rejected only because his name was unknown in the east. Riley authored a poem imitating the style of Edgar Allan Poe and submitted it to the Kokomo Dispatch under a fictitious name claiming it was a long lost Poe poem. The Dispatch published the poem and reported it as such. Riley and two other men who were part of the plot waited two weeks for the poem to be published by major newspapers in Chicago, Boston, and New York to gauge their reaction; they were disappointed. While a few newspapers believed the poem to be authentic, the majority did not, claiming the quality was too poor to be authored by Poe. An employee of the Dispatch learned the truth of the incident and reported it to the Kokomo Tribune, which published an expose that outed Riley as a conspirator behind the hoax. The revelation damaged the credibility of the Dispatch and harmed Riley's reputation. In the aftermath of the Poe plot, Riley was dismissed from the Democrat, so he returned to Greenfield to spend time writing poetry. Back home, he met Clara Louise Bottsford, a school teacher boarding in his father's home. They found they had much in common, particularly their love of literature. The couple began a twelve-year intermittent relationship which would be Riley's longest lasting. In mid-1878 the couple had their first breakup, caused partly by Riley's alcohol addiction. The event led Riley to make his first attempt to give up liquor. He joined a local temperance organization, but quit after a few weeks. Performing poet Without a steady income, his financial situation began to deteriorate. He began submitting his poems to more prominent literary magazines, including Scribner's Monthly, but was informed that although he showed promise, his work was still short of the standards required for use in their publications. Locally, he was still dealing with the stigma of the Poe plot. The Indianapolis Journal and other newspapers refused to accept his poetry, leaving Riley desperate for income. In January 1878 on the advice of a friend, Riley paid an entrance fee to join a traveling lecture circuit where he could give poetry readings. In exchange, he received a portion of the profit his performances earned. Such circuits were popular at the time, and Riley quickly earned a local reputation for his entertaining readings. In August 1878, Riley followed Indiana Governor James D. Williams as speaker at a civic event in a small town near Indianapolis. He recited a recently composed poem, "A Childhood Home of Long Ago," telling of life in pioneer Indiana. The poem was well received and was given good reviews by several newspapers. "Flying Islands of the Night" is the only play that Riley wrote and published. Authored while Riley was traveling with the Adelphians, but never performed, the play has similarities to A Midsummer Night's Dream, which Riley may have used as a model. Flying Islands concerns a kingdom besieged by evil forces of a sinister queen who is defeated eventually by an angel-like heroine. Most reviews were positive. Riley published the play and it became popular in the central Indiana area during late 1878, helping Riley to convince newspapers to again accept his poetry. In November 1879 he was offered a position as a columnist at the Indianapolis Journal and accepted after being encouraged by E.B. Matindale, the paper's chief editor. Although the play and his newspaper work helped expose him to a wider audience, the chief source of his increasing popularity was his performances on the lecture circuit. He made both dramatic and comedic readings of his poetry, and by early 1879 could guarantee large crowds whenever he performed. In an 1894 article, Hamlin Garland wrote that Riley's celebrity resulted from his reading talent, saying "his vibrant individual voice, his flexible lips, his droll glance, united to make him at once poet and comedian—comedian in the sense in which makes for tears as well as for laughter." Although he was a good performer, his acts were not entirely original in style; he frequently copied practices developed by Samuel Clemens and Will Carleton. His tour in 1880 took him to every city in Indiana where he was introduced by local dignitaries and other popular figures, including Maurice Thompson with whom he began to develop a close friendship. Developing and maintaining his publicity became a constant job, and received more of his attention as his fame grew. Keeping his alcohol addiction secret, maintaining the persona of a simple rural poet and a friendly common person became most important. Riley identified these traits as the basis of his popularity during the mid-1880s, and wrote of his need to maintain a fictional persona. He encouraged the stereotype by authoring poetry he thought would help build his identity. He was aided by editorials he authored and submitted to the Indianapolis Journal offering observations on events from his perspective as a "humble rural poet". He changed his appearance to look more mainstream, and began by shaving his mustache off and abandoning the flamboyant dress he employed in his early circuit tours. By 1880 his poems were beginning to be published nationally and were receiving positive reviews. "Tom Johnson's Quit" was carried by newspapers in twenty states, thanks in part to the careful cultivation of his popularity. Riley became frustrated that despite his growing acclaim, he found it difficult to achieve financial success. In the early 1880s, in addition to his steady performing, Riley began producing many poems to increase his income. Half of his poems were written during the period. The constant labor had adverse effects on his health, which was worsened by his drinking. At the urging of Maurice Thompson, he again attempted to stop drinking liquor, but was only able to give it up for a few months. Politics In March 1888, Riley traveled to Washington, D.C. where he had dinner at the White House with other members of the International Copyright League and President of the United States Grover Cleveland. Riley made a brief performance for the dignitaries at the event before speaking about the need for international copyright protections. Cleveland was enamored by Riley's performance and invited him back for a private meeting during which the two men discussed cultural topics. In the 1888 Presidential Election campaign, Riley's acquaintance Benjamin Harrison was nominated as the Republican candidate. Although Riley had shunned politics for most of his life, he gave Harrison a personal endorsement and participated in fund-raising events and vote stumping. The election was exceptionally partisan in Indiana, and Riley found the atmosphere of the campaign stressful; he vowed never to become involved with politics again. Upon Harrison's election, he suggested Riley be named the national poet laureate, but Congress failed to act on the request. Riley was still honored by Harrison and visited him at the White House on several occasions to perform at civic events. Pay problems and scandal Riley and Nye made arrangements with James Pond to make two national tours during 1888 and 1889. The tours were popular and generally sold out, with hundreds having to be turned away. The shows were usually forty-five minutes to an hour long and featured Riley reading often humorous poetry interspersed by stories and jokes from Nye. The shows were informal and the two men adjusted their performances based on their audiences reactions. Riley memorized forty of his poems for the shows to add to his own versatility. Many prominent literary and theatrical people attended the shows. At a New York City show in March 1888, Augustin Daly was so enthralled by the show he insisted on hosting the two men at a banquet with several leading Broadway theatre actors. Despite Riley serving as the act's main draw, he was not permitted to become an equal partner in the venture. Nye and Pond both received a percentage of the net profit, while Riley was paid a flat rate for each performance. In addition, because of Riley's past agreements with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, he was required to pay half of his fee to his agent Amos Walker. This caused the other men to profit more than Riley from his own work. To remedy this situation, Riley hired his brother-in-law Henry Eitel, an Indianapolis banker, to manage his finances and act on his behalf to try and extricate him from his contract. Despite discussions and assurances from Pond that he would work to address the problem, Eitel had no success. Pond ultimately made the situation worse by booking months of solid performances, not allowing Riley and Nye a day of rest. These events affected Riley physically and emotionally; he became despondent and began his worst period of alcoholism. During November 1889, the tour was forced to cancel several shows after Riley became severely inebriated at a stop in Madison, Wisconsin. Walker began monitoring Riley and denying him access to liquor, but Riley found ways to evade Walker. At a stop at the Masonic Temple Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky, in January 1890, Riley paid the hotel's bartender to sneak whiskey to his room. He became too drunk to perform, and was unable to travel to the next stop. Nye terminated the partnership and tour in response. The reason for the breakup could not be kept secret, and hotel staff reported to the Louisville Courier-Journal that they saw Riley in a drunken stupor walking around the hotel. The story made national news and Riley feared his career was ruined. He secretly left Louisville at night and returned to Indianapolis by train. Eitel defended Riley to the press in an effort to gain sympathy for Riley, explaining the abusive financial arrangements his partners had made. Riley however refused to speak to reporters and hid himself for weeks. Much to Riley's surprise, the news reports made him more popular than ever. Many people thought the stories were exaggerated, and Riley's carefully cultivated image made it difficult for the public to believe he was an alcoholic. Riley had stopped sending poetry to newspapers and magazines in the aftermath, but they soon began corresponding with him requesting that he resume writing. This encouraged Riley, and he made another attempt to give up liquor as he returned to his public career. The negative press did not end however, as Nye and Pond threatened to sue Riley for causing their tour to end prematurely. They claimed to have lost $20,000. Walker threatened a separate suit demanding $1,000. Riley hired Indianapolis lawyer William P. Fishback to represent him and the men settled out of court. The full details of the settlement were never disclosed, but whatever the case, Riley finally extricated himself from his old contracts and became a free agent. The exorbitant amount Riley was being sued for only reinforced public opinion that Riley had been mistreated by his partners, and helped him maintain his image. Nye and Riley remained good friends, and Riley later wrote that Pond and Walker were the source of the problems. Riley's poetry had become popular in Britain, in large part due to his book Old-Fashioned Roses. In May 1891 he traveled to England to make a tour and what he considered a literary pilgrimage. He landed in Liverpool and traveled first to Dumfries, Scotland, the home and burial place of Robert Burns. Riley had long been compared to Burns by critics because they both used dialect in their poetry and drew inspiration from their rural homes. He then traveled to Edinburgh, York, and London, reciting poetry for gatherings at each stop. Augustin Daly arranged for him to give a poetry reading to prominent British actors in London. Riley was warmly welcomed by its literary and theatrical community and he toured places that Shakespeare had frequented. Riley quickly tired of traveling abroad and began longing for home, writing to his nephew that he regretted having left the United States. He curtailed his journey and returned to New York City in August. He spent the next months in his Greenfield home attempting to write an epic poem, but after several attempts gave up, believing he did not possess the ability. By 1890, Riley had authored almost all of his famous poems. The few poems he did write during the 1890s were generally less well received by the public. As a solution, Riley and his publishers began reusing poetry from other books and printing some of his earliest works. When Neighborly Poems was published in 1891, a critic working for the Chicago Tribune pointed out the use of Riley's earliest works, commenting that Riley was using his popularity to push his crude earlier works onto the public only to make money. Riley's newest poems published in the 1894 book Armazindy received very negative reviews that referred to poems like "The Little Dog-Woggy" and "Jargon-Jingle" as "drivel" and to Riley as a "worn out genius." Most of his growing number of critics suggested that he ignored the quality of the poems for the sake of making money. National poet Riley had become very wealthy by the time he ended touring in 1895, and was earning $1,000 a week. Although he retired, he continued to make minor appearances. In 1896, Riley performed four shows in Denver. Most of the performances of his later life were at civic celebrations. He was a regular speaker at Decoration Day events and delivered poetry before the unveiling of monuments in Washington, D.C. Newspapers began referring to him as the "National Poet", "the poet laureate of America", and "the people's poet laureate". Riley wrote many of his patriotic poems for such events, including "The Soldier", "The Name of Old Glory", and his most famous such poem, "America!". The 1902 poem "America, Messiah of Nations" was written and read by Riley for the dedication of the Indianapolis Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. The only new poetry Riley published after the end of the century were elegies for famous friends. The poetic qualities of the poems were often poor, but they contained many popular sentiments concerning the deceased. Among those he eulogized were Benjamin Harrison, Lew Wallace, and Henry Lawton. Because of the poor quality of the poems, his friends and publishers requested that he stop writing them, but he refused. In 1897, Riley's publishers suggested that he create a multi-volume series of books containing his complete life works. With the help of his nephew, Riley began working to compile the books, which eventually totaled sixteen volumes and were finally completed in 1914. Such works were uncommon during the lives of writers, attesting to the uncommon popularity Riley had achieved. His works had become staples for Ivy League literature courses and universities began offering him honorary degrees. The first was Yale in 1902, followed by a Doctorate of Letters from the University of Pennsylvania in 1904. Wabash College and Indiana University granted him similar awards. In 1908 he was elected member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1912 they conferred upon him a special medal for poetry. Riley was influential in helping other poets start their careers, having particularly strong influences on Hamlin Garland, William Allen White, and Edgar Lee Masters. He discovered aspiring African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1892. Riley thought Dunbar's work was "worthy of applause", and wrote him letters of recommendation to help him get his work published. Declining health In 1901, Riley's doctor diagnosed him with neurasthenia, a nervous disorder, and recommended long periods of rest as a cure.[173] Riley remained ill for the rest of his life and relied on his landlords and family to aid in his care. During the winter months he moved to Miami, Florida, and during summer spent time with his family in Greenfield. He made only a few trips during the decade, including one to Mexico in 1906. He became very depressed by his condition, writing to his friends that he thought he could die at any moment, and often used alcohol for relief.[174] In March 1909, Riley was stricken a second time with Bell's palsy, and partial deafness, the symptoms only gradually eased over the course of the year.[175] Riley was a difficult patient, and generally refused to take any medicine except the patent medicines he had sold in his earlier years; the medicines often worsened his conditions, but his doctors could not sway his opinion.[176] On July 10, 1910 he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping for a quick recovery, his family kept the news from the press until September. Riley found the loss of use of his writing hand the worst part of the stroke, which served only to further depress him.[174][177] With his health so poor, he decided to work on a legacy by which to be remembered in Indianapolis. In 1911 he donated land and funds to build a new library on Pennsylvania Avenue.[178] By 1913, with the aid of a cane, Riley began to recover his ability to walk. His inability to write, however, nearly ended his production of poems. George Ade worked with him from 1910 through 1916 to write his last five poems and several short autobiographical sketches as Riley dictated. His publisher continued recycling old works into new books, which remained in high demand.[178] Since the mid-1880s, Riley had been the nation's most read poet, a trend that accelerated at the turn of the century. In 1912 Riley recorded readings of his most popular poetry to be sold by Victor Records. Riley was the subject of three paintings by T. C. Steele. The Indianapolis Arts Association commissioned a portrait of Riley to be created by world famous painter John Singer Sargent. Riley's image became a nationally known icon and many businesses capitalized on his popularity to sell their products; Hoosier Poet brand vegetables became a major trade-name in the midwest.[179] In 1912, the governor of Indiana instituted Riley Day on the poet's birthday. Schools were required to teach Riley's poems to their children, and banquet events were held in his honor around the state. In 1915 and 1916 the celebration was national after being proclaimed in most states. The annual celebration continued in Indiana until 1968.[180] In early 1916 Riley was filmed as part of a movie to celebrate Indiana's centennial, the video is on display at the Indiana State Library.[181][182] Death and legacy On July 22, 1916, Riley suffered a second stroke. He recovered enough during the day to speak and joke with his companions. He died before dawn the next morning, July 23.[183] Riley's death shocked the nation and made front page headlines in major newspapers.[184] President Woodrow Wilson wrote a brief note to Riley's family offering condolences on behalf the entire nation. Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston offered to allow Riley to lie in state at the Indiana Statehouse—Abraham Lincoln being the only other person to have previously received such an honor.[185] During the ten hours he lay in state on July 24, more than thirty-five thousand people filed past his bronze casket; the line was still miles long at the end of the day and thousands were turned away. The next day a private funeral ceremony was held and attended by many dignitaries. A large funeral procession then carried him to Crown Hill Cemetery where he was buried in a tomb at the top of the hill, the highest point in the city of Indianapolis.[186] Within a year of Riley's death many memorials were created, including several by the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association. The James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children was created and named in his honor by a group of wealthy benefactors and opened in 1924. In the following years, other memorials intended to benefit children were created, including Camp Riley for youth with disabilities.[187][188] The memorial foundation purchased the poet's Lockerbie home in Indianapolis and it is now maintained as a museum. The James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home is the only late-Victorian home in Indiana that is open to the public and the United States' only late-Victorian preservation, featuring authentic furniture and decor from that era. His birthplace and boyhood home, now the James Whitcomb Riley House, is preserved as a historical site.[189] A Liberty ship, commissioned April 23, 1942, was christened the SS James Whitcomb Riley. It served with the United States Maritime Commission until being scrapped in 1971. James Whitcomb Riley High School opened in South Bend, Indiana in 1924. In 1950, there was a James Whitcomb Riley Elementary School in Hammond, Indiana, but it was torn down in 2006. East Chicago, Indiana had a Riley School at one time, as did neighboring Gary, Indiana and Anderson, Indiana. One of New Castle, Indiana's elementary schools is named for Riley as is the road on which it is located. The former Greenfield High School was converted to Riley Elementary School and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 10-cent stamp honoring Riley.[190] As a lasting tribute, the citizens of Greenfield hold a festival every year in Riley's honor. Taking place the first or second weekend of October, the "Riley Days" festival traditionally commences with a flower parade in which local school children place flowers around Myra Reynolds Richards' statue of Riley on the county courthouse lawn, while a band plays lively music in honor of the poet. Weeks before the festival, the festival board has a queen contest. The 2010–2011 queen was Corinne Butler. The pageant has been going on many years in honor of the Hoosier poet[191] According to historian Elizabeth Van Allen, Riley was instrumental in helping form a midwestern cultural identity. The midwestern United States had no significant literary community before the 1880s.[192] The works of the Western Association of Writers, most notably those of Riley and Wallace, helped create the midwest's cultural identity and create a rival literary community to the established eastern literari. For this reason, and the publicity Riley's work created, he was commonly known as the "Hoosier Poet." Critical reception and style Riley was among the most popular writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, known for his "uncomplicated, sentimental, and humorous" writing.[195] Often writing his verses in dialect, his poetry caused readers to recall a nostalgic and simpler time in earlier American history. This gave his poetry a unique appeal during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the United States. Riley was a prolific writer who "achieved mass appeal partly due to his canny sense of marketing and publicity."[195] He published more than fifty books, mostly of poetry and humorous short stories, and sold millions of copies.[195] Riley is often remembered for his most famous poems, including the "The Raggedy Man" and "Little Orphant Annie". Many of his poems, including those, where partially autobiographical, as he used events and people from his childhood as an inspiration for subject matter.[195] His poems often contained morals and warnings for children, containing messages telling children to care for the less fortunate of society. David Galens and Van Allen both see these messages as Riley's subtle response to the turbulent economic times of the Gilded Age and the growing progressive movement.[196] Riley believed that urbanization robbed children of their innocence and sincerity, and in his poems he attempted to introduce and idolize characters who had not lost those qualities.[197] His children's poems are "exuberant, performative, and often display Riley's penchant for using humorous characterization, repetition, and dialect to make his poetry accessible to a wide-ranging audience."[195][198] Although hinted at indirectly in some poems, Riley wrote very little on serious subject matter, and actually mocked attempts at serious poetry. Only a few of his sentimental poems concerned serious subjects. "Little Mandy's Christmas-Tree", "The Absence of Little Wesley", and "The Happy Little Cripple" were about poverty, the death of a child, and disabilities. Like his children's poems, they too contained morals, suggesting society should pity the downtrodden and be charitable.[195][198] Riley wrote gentle and romantic poems that were not in dialect. They generally consisted of sonnets and were strongly influenced by the works of John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His standard English poetry was never as popular as his Hoosier dialect poems.[195] Still less popular were the poems Riley authored in his later years; most were to commemorate important events of American history and to eulogize the dead.[195] Riley's contemporaries acclaimed him "America's best-loved poet".[195][198] In 1920, Henry Beers lauded the works of Riley "as natural and unaffected, with none of the discontent and deep thought of cultured song."[195] Samuel Clemens, William Dean Howells, and Hamlin Garland, each praised Riley's work and the idealism he expressed in his poetry. Only a few critics of the period found fault with Riley's works. Ambrose Bierce criticized Riley for his frequent use of dialect. Bierce accused Riley of using dialect to "cover up [the] faulty construction" of his poems.[195] Edgar Lee Masters found Riley's work to be superficial, claiming it lacked irony and that he had only a "narrow emotional range".[195] By the 1930s popular critical opinion towards Riley's works began to shift in favor of the negative reviews. In 1951, James T. Farrell said Riley's works were "cliched." Galens wrote that modern critics consider Riley to be a "minor poet, whose work—provincial, sentimental, and superficial though it may have been—nevertheless struck a chord with a mass audience in a time of enormous cultural change."[195] Thomas C. Johnson wrote that what most interests modern critics was Riley's ability to market his work, saying he had a unique understanding of "how to commodify his own image and the nostalgic dreams of an anxious nation."[195] Among the earliest widespread criticisms of Riley were opinions that his dialect writing did not actually represent the true dialect of central Indiana. In 1970 Peter Revell wrote that Riley's dialect was more similar to the poor speech of a child rather than the dialect of his region. Revell made extensive comparison to historical texts and Riley's dialect usage. Philip Greasley wrote that that while "some critics have dismissed him as sub-literary, insincere, and an artificial entertainer, his defenders reply that an author so popular with millions of people in different walks of life must contribute something of value, and that his faults, if any, can be ignored." References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Whitcomb_Riley

Paul Verlaine est un écrivain et poète français du xixe siècle, né à Metz (Moselle) le 30 mars 1844 et mort à Paris le 8 janvier 1896 (à 51 ans). Il s'essaie à la poésie et publie son premier recueil, Poèmes saturniens en 1866, à 22 ans. Sa vie est bouleversée quand il rencontre Arthur Rimbaud en septembre 1871. Leur vie amoureuse tumultueuse et errante en Angleterre et en Belgique débouche sur la scène violente où, à Bruxelles, Verlaine blesse superficiellement au poignet celui qu'il appelle son « époux infernal » : jugé et condamné, il reste en prison jusqu'au début de 1875, renouant avec le catholicisme de son enfance et écrivant des poèmes qui prendront place dans ses recueils suivants : Sagesse (1880), Jadis et Naguère (1884) et Parallèlement (1889). Usé par l'alcool et la maladie, Verlaine meurt à 51 ans, le 8 janvier 1896, d'une pneumonie aiguë. Il est inhumé à Paris au cimetière des Batignolles (11e division). Archétype du poète maudit, Verlaine est reconnu comme un maître par la génération suivante. Son style — fait de musicalité et de fluidité jouant avec les rythmes impairs — et la tonalité de nombre de ses poèmes — associant mélancolie et clairs-obscurs — révèlent, au-delà de l'apparente simplicité formelle, une profonde sensibilité, en résonance avec l'inspiration de certains artistes contemporains, des peintres impressionnistes ou des compositeurs (tels Reynaldo Hahn, Gabriel Fauré et Claude Debussy, qui mettront d'ailleurs en musique plusieurs de ses poèmes). Enfance Après treize ans de mariage, Nicolas-Auguste Verlaine et son épouse Élisa-Stéphanie Dehée donnent naissance, le 30 mars 1844, au 2 rue de la Haute-Pierre, à Metz, à un fils qu'ils prénomment Paul-Marie en reconnaissance à la Vierge Marie pour cette naissance tardive, Élisa ayant fait auparavant trois fausses couches. Catholiques, ils le font baptiser en l'église Notre-Dame de Metz. Paul restera le fils unique de cette famille de petite-bourgeoisie assez aisée qui élève aussi, depuis 1836, une cousine orpheline prénommée Élisa. Son père, militaire de carrière, atteint le grade de capitaine avant de démissionner de l'armée en 1851 : la famille Verlaine quitte alors Metz pour Paris. Enfant aimé et plutôt appliqué, il est mis en pension à l'institution Landry, 32 rue Chaptal, les enfants pensionnaires à Landry suivent leurs cours au lycée Condorcet. Paul Verlaine devient un adolescent difficile, et obtient finalement son baccalauréat en 1862. Entrée dans la vie adulte C'est durant sa jeunesse qu'il s'essaie à la poésie. En effet, en 1860, la pension est pour lui source d'ennui et de dépaysement. Admirateur de Baudelaire, et s'intéressant à la faune africaine, il exprime son mal-être dû à l'éloignement de son foyer, à travers une poésie dénuée de tout message si ce n'est celui de ses sentiments, Les Girafes. « Je crois que les longs cous jamais ne se plairont/ Dans ce lieu si lointain, dans ce si bel endroit/ Qui est mon Alaska, pays où nul ne va / Car ce n'est que chez eux que comblés ils seront ». Ce court poème en quatre alexandrins reste sa première approche sur le domaine poétique, même s'il ne sera publié qu'à titre posthume[réf. nécessaire]. Bachelier, il s'inscrit en faculté de droit, mais abandonne ses études, leur préférant la fréquentation des cafés et des cercles littéraires parisiens. Il s'intéresse plus sérieusement à la poésie et, en août 1863, une revue publie son premier poème connu de son vivant : Monsieur Prudhomme, portrait satirique du bourgeois qu'il reprendra dans son premier recueil. Il collabore au premier Parnasse contemporain et publie à 22 ans en 1866 les Poèmes saturniens qui traduisent l'influence de Baudelaire, mais aussi une musique personnelle orientée vers « la Sensation rendue ». En 1869, paraît le petit recueil Fêtes galantes, fantaisies inspirées par les toiles des peintres du xviiie siècle que le Louvre vient d'exposer dans de nouvelles salles. Dans la même période, son père, inquiet de son avenir, le fait entrer en 1864 comme employé dans une compagnie d'assurance, puis, quelques mois plus tard, à la mairie du 9e arrondissement, puis à l'hôtel de ville de Paris. Il vit toujours chez ses parents et, après le décès du père en décembre 1865, chez sa mère avec laquelle il entretiendra une relation de proximité et de violence toute sa vie. Paul Verlaine est aussi très proche de sa chère cousine Élisa, orpheline recueillie dès 183611 et élevée par les Verlaine avec leur fils : il souhaitait secrètement l'épouser, mais elle se marie en 1861 avec un entrepreneur aisé (il possède une sucrerie dans le Nord) ce qui permettra à Élisa de l'aider à faire paraître son premier recueil (Poèmes saturniens, 1866). La mort en couches en 1867 de celle dont il restait amoureux le fait basculer un peu plus dans l'excès d'alcool qui le rend violent : il tente même plusieurs fois de tuer sa mère. Celle-ci l'encourage à épouser Mathilde Mauté qu'un ami lui a fait rencontrer : il lui adresse des poèmes apaisés et affectueux qu'il reprendra en partie dans La Bonne Chanson, recueil publié le 12 juin 1870, mais mis en vente seulement l'année suivante, après la guerre et la Commune. Le mariage a lieu le 11 août 1870 (Paul a 26 ans et Mathilde, 17) ; un enfant, Georges, naît le 30 octobre 1871. Les références Wikipedia—https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Verlaine

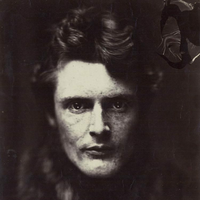

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882) was an English poet, illustrator, painter and translator. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, and was later to be the main inspiration for a second generation of artists and writers influenced by the movement, most notably William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. His work also influenced the European Symbolists and was a major precursor of the Aesthetic movement.

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in lowercase letters as e.e. cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization, below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, más conocida como Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, (San Miguel Nepantla, 12 de noviembre de 1651—Ciudad de México, 17 de abril de 1695) fue una religiosa y escritora novohispana del Barroco en el Siglo de Oro. Cultivó la lírica, el auto sacramental y el teatro, así como la prosa. Por la importancia de su obra, recibió los sobrenombres de «el fénix de América», «la Décima Musa» o «la Décima Musa mexicana». A muy temprana edad aprendió a leer y a escribir. Perteneció a la corte de Antonio de Toledo y Salazar, marqués de Mancera y 25° virrey novohispano. En 1667 ingresó a la vida religiosa a fin de consagrarse por completo a la literatura. Sus más importantes mecenas fueron los marqueses de la Laguna, virreyes de la Nueva España, quienes publicaron sus obras en la España peninsular. Murió a causa de una epidemia el 17 de abril de 1695.

Rosario Castellanos Figueroa (Ciudad de México, 25 de mayo de 1925 - Tel Aviv, 7 de agosto de 1974) fue una escritora, periodista y diplomática mexicana, considerada una de las literatas mexicanas más importantes del siglo XX. ...si es necesaria una definición para el papel de identidad, apunte que soy una mujer de buenas intenciones y que he pavimentado un camino directo y fácil al infierno. –Rosario Castellanos

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American lyric poet. She was born Sarah Trevor Teasdale in St. Louis, Missouri, and used the name Sara Teasdale Filsinger after her marriage in 1914. She had such poor health for so much of her childhood, home schooled until age 9, that it was only at age 10 that she was well enough to begin school. She started at Mary Institute in 1898, but switched to Hosmer Hall in 1899, graduating in 1903. I Shall Not Care WHEN I am dead and over me bright April Shakes out her rain-drenched hair, Tho' you should lean above me broken-hearted, I shall not care. I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful When rain bends down the bough, And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted Than you are now.

Gustavo Adolfo Domínguez Bastida (Sevilla, 17 de febrero de 1836 – Madrid, 22 de diciembre de 1870), más conocido como Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, fue un poeta y narrador español, perteneciente al movimiento del Romanticismo, aunque escribió en una etapa literaria perteneciente al Realismo. Por ser un romántico tardío, ha sido asociado igualmente con el movimiento posromántico. Aunque, mientras vivió, fue moderadamente conocido, sólo comenzó a ganar verdadero prestigio cuando, tras su muerte, fueron publicadas muchas de sus obras. Nació en Sevilla el 17 de febrero de 1836, hijo del pintor José Domínguez Insausti, que firmaba sus cuadros con el apellido de sus antepasados como José Domínguez Bécquer. Sus más conocidos trabajos son sus Rimas y Leyendas. Los poemas e historias incluidos en esta colección son esenciales para el estudio de la Literatura hispana, siendo ampliamente reconocidos por su influencia posterior. Gustavo Adolfo por Mercedes de Velilla En la margen del Betis murmurante, donde expira, entre flores, la onda inquieta, en monumento digno del poeta, su hermosa estatua se alzará triunfante. El sol le ofrecerá nimbo radiante; sus perfumes, la rosa y la violeta; la aurora, el beso de su luz discreta; el crepúsculo, brisa refrescante. Traerá la noche espíritus y hadas, visiones de Leyendas peregrinas que poblarán las verdes enramadas. La alondra y las obscuras golondrinas cantarán, al lucir las alboradas, las Rimas inmortales y divinas.

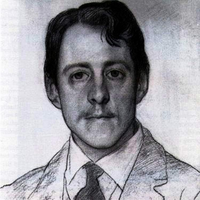

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (17 August 1840– 10 September 1922) (sometimes spelled “Wilfred”) was an English poet and writer. He and his wife, Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodlines through their farm, the Crabbet Arabian Stud. He was best known for his poetry, which was published in a collected edition in 1914, but also wrote a number of political essays and polemics. Blunt is also known for his views against imperialism, viewed as relatively enlightened for his time. Early life Blunt was born at Petworth House in Sussex and served in the Diplomatic Service from 1858 to 1869. He was raised in the faith of his mother, a Catholic convert, and educated at Twyford School, Stonyhurst, and at St Mary’s College, Oscott. His most memorable line of poetry on the subject comes from Satan Absolved (1899), where the devil, answering a Kiplingesque remark by God, snaps back: ‘The white man’s burden, Lord, is the burden of his cash’ Here, Longford explains, 'Blunt stood Rudyard Kipling’s familiar concept on its head, arguing that the imperialists’ burden is not their moral responsibility for the colonised peoples, but their urge to make money out of them.' Personal life In 1869, Blunt married Lady Anne Noel, the daughter of the Earl of Lovelace and Ada Lovelace, and granddaughter of Lord Byron. Together the Blunts travelled through Spain, Algeria, Egypt, the Syrian Desert, and extensively in the Middle East and India. Based upon pure-blooded Arabian horses they obtained in Egypt and the Nejd, they co-founded Crabbet Arabian Stud, and later purchased a property near Cairo, named Sheykh Obeyd which housed their horse breeding operation in Egypt. In 1882, he championed the cause of Urabi Pasha, which led him to be banned from entering Egypt for four years. Blunt generally opposed British imperialism as a matter of philosophy, and his support for Irish causes led to his imprisonment in 1888. Wilfrid and Lady Anne’s only child to live to maturity was Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth, later known as Lady Wentworth. As an adult, she was married in Cairo but moved permanently to the Crabbet Park Estate in 1904. Wilfrid had a number of mistresses, among them a long term relationship with the courtesan Catherine “Skittles” Walters, and the Pre-Raphaelite beauty, Jane Morris. Eventually, he moved another mistress, Dorothy Carleton, into his home. This event triggered Lady Anne’s legal separation from him in 1906. At that time, Lady Anne signed a Deed of Partition drawn up by Wilfrid. Under its terms, unfavourable to Lady Anne, she kept the Crabbet Park property (where their daughter Judith lived) and half the horses, while Blunt took Caxtons Farm, also known as Newbuildings, and the rest of the stock. Always struggling with financial concerns and chemical dependency issues, Wilfrid sold off numerous horses to pay debts and constantly attempted to obtain additional assets. Lady Anne left the management of her properties to Judith, and spent many months of every year in Egypt at the Sheykh Obeyd estate, moving there permanently in 1915. Due primarily to the manoeuvering of Wilfrid in an attempt to disinherit Judith and obtain the entire Crabbet property for himself, Judith and her mother were estranged at the time of Lady Anne’s death in 1917. As a result, Lady Anne’s share of the Crabbet Stud passed to Judith’s daughters, under the oversight of an independent trustee. Blunt filed a lawsuit soon afterward. Ownership of the Arabian horses went back and forth between the estates of father and daughter in the following years. Blunt sold more horses to pay off debts and shot at least four in an attempt to spite his daughter, an action which required intervention of the trustee of the estate with a court injunction to prevent him from further “dissipating the assets” of the estate. The lawsuit was settled in favour of the granddaughters in 1920, and Judith bought their share from the trustee, combining it with her own assets and reuniting the stud. Father and daughter briefly reconciled shortly before Wilfrid Scawen Blunt’s death in 1922, but his promise to rewrite his will to restore Judith’s inheritance never materialised. Blunt was a friend of Winston Churchill, aiding him in his 1906 biography of his father, Randolph Churchill, whom Blunt had befriended years earlier in 1883 at a chess tournament. Work in Africa In the early 1880s, Britain was struggling with its Egyptian colony. Wilfrid Blunt was sent to notify Sir Edward Malet, the British agent, as to the Egyptian public opinion concerning the recent changes in government and development policies. In mid-December 1881, Blunt met with Ahmed ‘Urabi, known as Arabi or 'El Wahid’ (the Only One) due to his popularity with the Egyptians. Arabi was impressed with Blunt’s enthusiasm and appreciation of his culture. Their mutual respect created an environment in which Arabi could peacefully explain the reasoning behind a new patriotic movement, 'Egypt for the Egyptians’. Over the course of several days, Arabi explained the complicated background of the revolutionaries and their determination to rid themselves of the Turkish oligarchy. Wilfrid Blunt was vital in the relay of this information to the British empire although his anti-imperialist views were disregarded and England mounted further campaigns in the Sudan in 1885 and 1896–98. Egyptian Garden scandal In 1901, a pack of fox hounds was shipped over to Cairo to entertain the army officers, and subsequently a foxhunt took place in the desert near Cairo. The fox was chased into Blunt’s garden, and the hounds and hunt followed it. As well as a house and garden, the land contained the Blunt’s Sheykh Obeyd stud farm, housing a number of valuable Arabian horses. Blunt’s staff challenged the trespassers– who, though army officers, were not in uniform– and beat them when they refused to turn back. For this, the staff were accused of assault against army officers and imprisoned. Blunt made strenuous efforts to free his staff, much to the embarrassment of the British army officers and civil servants involved. Bibliography * Sonnets and Songs. By Proteus. John Murray, 1875 * Aubrey de Vere (ed.): Proteus and Amadeus: A Correspondence Kegan Paul, 1878 * The Love Sonnets of Proteus. Kegan Paul, 1881 * The Future of Islam Kegan Paul, Trench, London 1882 * Esther (1892) * Griselda Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1893 * The Quatrains of Youth (1898) * Satan Absolved: A Victorian Mystery. J. Lane, London 1899 * Seven Golden Odes of Pagan Arabia (1903) * Atrocities of Justice under the English Rule in Egypt. T. F. Unwin, London 1907. * Secret History of the English Occupation of Egypt Knopf, 1907 * India under Ripon; A Private Diary T. Fisher Unwin, London 1909. * Gordon at Khartoum. S. Swift, London 1911. * The Land War in Ireland. S. Swift, London 1912 * The Poetical Works. 2 Vols. . Macmillan, London 1914 * My Diaries. Secker, London 1919; 2 Vols. Knopf, New York 1921 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilfrid_Scawen_Blunt

María Elena Walsh (Ramos Mejía, Buenos Aires, 1 de febrero de 1930 – Buenos Aires, 10 de enero de 2011) fue una poetisa, escritora, música, cantautora, dramaturga y compositora argentina, especialmente famosa por sus obras infantiles, que ha sido considerada como «mito viviente, prócer cultural y blasón de casi todas las infancias». Por su parte, el escritor Leopoldo Brizuela ha puesto de relieve el valor de su creación diciendo que «lo escrito por María Elena configura la obra más importante de todos los tiempos en su género, comparable a la Alicia de Lewis Carroll o a Pinocho; una obra que revolucionó la manera en que se entendía la relación entre poesía e infancia.» Maria Elena Los juglares son eternos Porque viven en la voz del viento. Elegiste irte en un día señalado, Juglar esquivo de la voz de caña, Un día que conjuga dos dolores, Otro como tú, eligió ese día. En un tiempo, él también Creyó en las palabras y su fuerza y dulzura Para calmar las olas de las duras tempestades Pero sin fe en sí mismo Abandonó en la lucha La consolación de la poesía. Nos diste y nos dejaste Sin reparo, ni medida, ni especulaciones varias, Nos diste así, tranquilamente Como se dan las aguas a los mares, Luego de que atraviesan la montaña. Fuiste tierna y dura A un mismo tiempo; A veces no entendías, Tanta estupidez, Tanta locura, Tanta falta de amor, Tanto destino, Tanta circular versión Tan repetida, Tanta malevolencia. Yo canté contigo Y les canté muy quedo En tiempos que las sombras eran muchas A aquellos que tomados de mi vida Eran la vida toda para mí. Y siempre te canté Cuando en el alma La duda de quien soy y a donde vago Llenaba de tristeza la esperanza Y entonces fui cigarra, Como tú, En noches negras. María Elena, No hace falta mencionar siquiera tu apellido, Siempre serás la María Elena Del tinglado y la luz.

Alfonsina Storni Martignoni (Sala Capriasca, Suiza, 29 de mayo de 1892 – Mar del Plata, Argentina, 25 de octubre de 1938) fue una poetisa y escritora argentina del modernismo. Su prosa es feminista y, según la crítica, posee una originalidad que cambió el sentido de las letras de Latinoamérica. En su poesía deja de lado el erotismo y aborda el tema desde un punto de vista más abstracto y reflexivo. Sus composiciones reflejan, además, la enfermedad que padeció durante gran parte de su vida y muestran la espera del punto final de su vida, expresándolo mediante el dolor, el miedo y otros sentimientos desmotivacionales.

English Romantic poet John Keats was born on October 31, 1795, in London. The oldest of four children, he lost both his parents at a young age. His father, a livery-stable keeper, died when Keats was eight; his mother died of tuberculosis six years later. After his mother's death, Keats's maternal grandmother appointed two London merchants, Richard Abbey and John Rowland Sandell, as guardians. Abbey, a prosperous tea broker, assumed the bulk of this responsibility, while Sandell played only a minor role. When Keats was fifteen, Abbey withdrew him from the Clarke School, Enfield, to apprentice with an apothecary-surgeon and study medicine in a London hospital. In 1816 Keats became a licensed apothecary, but he never practiced his profession, deciding instead to write poetry.

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869– 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. His most famous work, For the Fallen, is well known for being used in Remembrance Sunday services. Pre-war life Laurence Binyon was born in Lancaster, Lancashire, England. His parents were Frederick Binyon, and Mary Dockray. Mary’s father, Robert Benson Dockray, was the main engineer of the London and Birmingham Railway. The family were Quakers. Binyon studied at St Paul’s School, London. Then he read Classics (Honour Moderations) at Trinity College, Oxford, where he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1891. Immediately after graduating in 1893, Binyon started working for the Department of Printed Books of the British Museum, writing catalogues for the museum and art monographs for himself. In 1895 his first book, Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century, was published. In that same year, Binyon moved into the Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, under Campbell Dodgson. In 1909, Binyon became its Assistant Keeper, and in 1913 he was made the Keeper of the new Sub-Department of Oriental Prints and Drawings. Around this time he played a crucial role in the formation of Modernism in London by introducing young Imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington and H.D. to East Asian visual art and literature. Many of Binyon’s books produced while at the Museum were influenced by his own sensibilities as a poet, although some are works of plain scholarship– such as his four-volume catalogue of all the Museum’s English drawings, and his seminal catalogue of Chinese and Japanese prints. In 1904 he married historian Cicely Margaret Powell, and the couple had three daughters. During those years, Binyon belonged to a circle of artists, as a regular patron of the Wiener Cafe of London. His fellow intellectuals there were Ezra Pound, Sir William Rothenstein, Walter Sickert, Charles Ricketts, Lucien Pissarro and Edmund Dulac. Binyon’s reputation before the war was such that, on the death of the Poet Laureate Alfred Austin in 1913, Binyon was among the names mentioned in the press as his likely successor (others named included Thomas Hardy, John Masefield and Rudyard Kipling; the post went to Robert Bridges). For the Fallen Moved by the opening of the Great War and the already high number of casualties of the British Expeditionary Force, in 1914 Laurence Binyon wrote his For the Fallen, with its Ode of Remembrance, as he was visiting the cliffs on the north Cornwall coast, either at Polzeath or at Portreath (at each of which places there is a plaque commemorating the event, though Binyon himself mentioned Polzeath in a 1939 interview. The confusion may be related to Porteath Farm being near Polzeath). The piece was published by The Times newspaper in September, when public feeling was affected by the recent Battle of Marne. Today Binyon’s most famous poem, For the Fallen, is often recited at Remembrance Sunday services in the UK; is an integral part of Anzac Day services in Australia and New Zealand and of the 11 November Remembrance Day services in Canada. The third and fourth verses of the poem (although often just the fourth) have thus been claimed as a tribute to all casualties of war, regardless of nation. They went with songs to the battle, they were young. Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, We will remember them. They mingle not with their laughing comrades again; They sit no more at familiar tables of home; They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; They sleep beyond England’s foam Three of Binyon’s poems, including “For the Fallen”, were set by Sir Edward Elgar in his last major orchestra/choral work, The Spirit of England. In 1915, despite being too old to enlist in the First World War, Laurence Binyon volunteered at a British hospital for French soldiers, Hôpital Temporaire d’Arc-en-Barrois, Haute-Marne, France, working briefly as a hospital orderly. He returned in the summer of 1916 and took care of soldiers taken in from the Verdun battlefield. He wrote about his experiences in For Dauntless France (1918) and his poems, “Fetching the Wounded” and “The Distant Guns”, were inspired by his hospital service in Arc-en-Barrois. Artists Rifles, a CD audiobook published in 2004, includes a reading of For the Fallen by Binyon himself. The recording itself is undated and appeared on a 78 rpm disc issued in Japan. Other Great War poets heard on the CD include Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, David Jones and Edgell Rickword. Post-war life After the war, he returned to the British Museum and wrote numerous books on art; in particular on William Blake, Persian art, and Japanese art. His work on ancient Japanese and Chinese cultures offered strongly contextualised examples that inspired, among others, the poets Ezra Pound and W. B. Yeats. His work on Blake and his followers kept alive the then nearly-forgotten memory of the work of Samuel Palmer. Binyon’s duality of interests continued the traditional interest of British visionary Romanticism in the rich strangeness of Mediterranean and Oriental cultures. In 1931, his two volume Collected Poems appeared. In 1932, Binyon rose to be the Keeper of the Prints and Drawings Department, yet in 1933 he retired from the British Museum. He went to live in the country at Westridge Green, near Streatley (where his daughters also came to live during the Second World War). He continued writing poetry. In 1933–1934, Binyon was appointed Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. He delivered a series of lectures on The Spirit of Man in Asian Art, which were published in 1935. Binyon continued his academic work: in May 1939 he gave the prestigious Romanes Lecture in Oxford on Art and Freedom, and in 1940 he was appointed the Byron Professor of English Literature at University of Athens. He worked there until forced to leave, narrowly escaping the German invasion of Greece in April 1941 . He was succeeded by Lord Dunsany, who held the chair in 1940-1941. Binyon had been friends with Ezra Pound since around 1909, and in the 1930s the two became especially close; Pound affectionately called him “BinBin”, and assisted Binyon with his translation of Dante. Another protégé was Arthur Waley, whom Binyon employed at the British Museum. Between 1933 and 1943, Binyon published his acclaimed translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in an English version of terza rima, made with some editorial assistance by Ezra Pound. Its readership was dramatically increased when Paolo Milano selected it for the “The Portable Dante” in Viking’s Portable Library series. Binyon significantly revised his translation of all three parts for the project, and the volume went through three major editions and eight printings (while other volumes in the same series went out of print) before being replaced by the Mark Musa translation in 1981. At his death he was also working on a major three-part Arthurian trilogy, the first part of which was published after his death as The Madness of Merlin (1947). He died in Dunedin Nursing Home, Bath Road, Reading, on 10 March 1943 after an operation. A funeral service was held at Trinity College Chapel, Oxford, on 13 March 1943. There is a slate memorial in St. Mary’s Church, Aldworth, where Binyon’s ashes were scattered. On 11 November 1985, Binyon was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The inscription on the stone quotes a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Daughters His three daughters Helen, Margaret and Nicolete became artists. Helen Binyon (1904–1979) studied with Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious, illustrating many books for the Oxford University Press, and was also a marionettist. She later taught puppetry and published Puppetry Today (1966) and Professional Puppetry in England (1973). Margaret Binyon wrote children’s books, which were illustrated by Helen. Nicolete, as Nicolete Gray, was a distinguished calligrapher and art scholar. Bibliography of key works Poems and verse * Lyric Poems (1894) * Porphyrion and other Poems (1898) * Odes (1901) * Death of Adam and Other Poems (1904) * London Visions (1908) * England and Other Poems (1909) * “For The Fallen”, The Times, 21 September 1914 * Winnowing Fan (1914) * The Anvil (1916) * The Cause (1917) * The New World: Poems (1918) * The Idols (1928) * Collected Poems Vol 1: London Visions, Narrative Poems, Translations. (1931) * Collected Poems Vol 2: Lyrical Poems. (1931) * The North Star and Other Poems (1941) * The Burning of the Leaves and Other Poems (1944) * The Madness of Merlin (1947) In 1915 Cyril Rootham set “For the Fallen” for chorus and orchestra, first performed in 1919 by the Cambridge University Musical Society conducted by the composer. Edward Elgar set to music three of Binyon’s poems ("The Fourth of August", “To Women”, and “For the Fallen”, published within the collection “The Winnowing Fan”) as The Spirit of England, Op. 80, for tenor or soprano solo, chorus and orchestra (1917). English arts and myth * Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century (1895), Binyon’s first book on painting * John Crone and John Sell Cotman (1897) * William Blake: Being all his Woodcuts Photographically Reproduced in Facsimile (1902) * English Poetry in its relation to painting and the other arts (1918) * Drawings and Engravings of William Blake (1922) * Arthur: A Tragedy (1923) * The Followers of William Blake (1925) * The Engraved Designs of William Blake (1926) * Landscape in English Art and Poetry (1931) * English Watercolours (1933) * Gerard Hopkins and his influence (1939) * Art and freedom. (The Romanes lecture, delivered 25 May 1939). Oxford: The Clarendon press, (1939) Japanese and Persian arts * Painting in the Far East (1908) * Japanese Art (1909) * Flight of the Dragon (1911) * The Court Painters of the Grand Moguls (1921) * Japanese Colour Prints (1923) * The Poems of Nizami (1928) (Translation) * Persian Miniature Painting (1933) * The Spirit of Man in Asian Art (1936) Autobiography * For Dauntless France (1918) (War memoir) Biography * Botticelli (1913) * Akbar (1932) Stage plays * Brief Candles A verse-drama about the decision of Richard III to dispatch his two nephews * “Paris and Oenone”, 1906 * Godstow Nunnery: Play * Boadicea; A Play in eight Scenes * Attila: a Tragedy in Four Acts * Ayuli: a Play in three Acts and an Epilogue * Sophro the Wise: a Play for Children * (Most of the above were written for John Masefield’s theatre). * Charles Villiers Stanford wrote incidental music for Attila in 1907. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurence_Binyon

Jean de La Fontaine, né le 8 juillet 1621 à Château-Thierry et mort le 13 avril 1695 à Paris, est un poète français de grande renommée, principalement pour ses Fables et dans une moindre mesure pour ses contes. On lui doit également des poèmes divers, des pièces de théâtre et des livrets d’opéra qui confirment son ambition de moraliste. Proche de Nicolas Fouquet, Jean de La Fontaine reste à l’écart de la cour royale mais fréquente les salons comme celui de Madame de La Sablière et malgré des oppositions, il est reçu à l’Académie française en 1684. Mêlé aux débats de l’époque, il se range dans le parti des Anciens dans la fameuse Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes.

Eugène Grindel, dit Paul Éluardais né à Saint-Denis le 14 décembre 1895 et mort à Charenton-le-Pont le 18 novembre 1952 (à 56 ans). En 1916, il choisit le nom de Paul Éluard, hérité de sa grand-mère, Félicie. Il adhère au dadaïsme et devient l’un des piliers du surréalisme en ouvrant la voie à une action artistique politiquement engagée auprès du Parti communiste. Il est connu également sous les noms de plume de Didier Desroches et de Brun.

Vicente García-Huidobro Fernández (Santiago, 10 de enero de 1893 – Cartagena, 2 de enero de 1948), más conocido como Vicente Huidobro, fue un poeta chileno. Iniciador y exponente del creacionismo, es considerado uno de los más destacados poetas chilenos, junto con Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda y Pablo de Rokha. Nació en el seno de una familia adinerada, relacionada con la política y la banca. Su padre era el heredero del marquesado de Casa Real y su madre, una activista feminista y anfitriona de numerosas veladas literarias.