Info

Jack Spicer (January 30, 1925– August 17, 1965) was an American poet often identified with the San Francisco Renaissance. In 2009, My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer won the American Book Award for poetry. Life and work Spicer was born in Los Angeles, where he later graduated from Fairfax High School in 1942, and attended the University of Redlands from 1943-45. He spent most of his writing-life in San Francisco and spent the years 1945 to 1950 and 1952 to 1955 at the University of California, Berkeley, where he began writing, doing work as a research-linguist, and publishing some poetry (though he disdained publishing). During this time he searched out fellow poets, but it was through his alliance with Robert Duncan and Robin Blaser that Spicer forged a new kind of poetry, and together they referred to their common work as the Berkeley Renaissance. The three, who were all gay, also educated younger poets in their circle about their “queer genealogy”, Rimbaud, Lorca, and other gay writers. Spicer’s poetry of this period is collected in One Night Stand and Other Poems (1980). His Imaginary Elegies, later collected in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry 1945-1960 anthology, were written around this time. In 1954, he co-founded the Six Gallery in San Francisco, which soon became famous as the scene of the October 1955 Six Gallery reading that launched the West Coast Beat movement. In 1955, Spicer moved to New York and then to Boston, where he worked for a time in the Rare Book Room of Boston Public Library. Blaser was also in Boston at this time, and the pair made contact with a number of local poets, including John Wieners, Stephen Jonas, and Joe Dunn. Spicer returned to San Francisco in 1956 and started working on After Lorca. This book represented a major change in direction for two reasons. Firstly, he came to the conclusion that stand-alone poems (which Spicer referred to as his one-night stands) were unsatisfactory and that henceforth he would compose serial poems. In fact, he wrote to Blaser that 'all my stuff from the past (except the Elegies and Troilus) looks foul to me.' Secondly, in writing After Lorca, he began to practice what he called “poetry as dictation”. His interest in the work of Federico García Lorca, especially as it involved the cante jondo ideal, also brought him near the poetics of the deep image group. The Troilus referred to was Spicer’s then unpublished play of that name. The play finally appeared in print in 2004, edited by Aaron Kunin, in issue 3 of No - A Journal of the Arts. In 1957, Spicer ran a workshop called Poetry as Magic at San Francisco State College, which was attended by Duncan, Helen Adam, James Broughton, Joe Dunn, Jack Gilbert, and George Stanley. He also participated in, and sometimes hosted, Blabbermouth Night at a literary bar called The Place. This was a kind of contest of improvised poetry and encouraged Spicer’s view of poetry as being dictated to the poet. After many years of alcohol abuse, Spicer fell into a prehepatic coma in his apartment building elevator, and later died aged 40 in the poverty ward of San Francisco General Hospital on August 17, 1965. Legacy Spicer’s view of the role of language in the process of writing poetry was probably the result of his knowledge of modern pre-Chomskyan linguistics and his experience as a research-linguist at Berkeley. In the legendary Vancouver lectures he elucidated his ideas on “transmissions” (dictations) from the Outside, using the comparison of the poet as crystal-set or radio receiving transmissions from outer space, or Martian transmissions. Although seemingly far-fetched, his view of language as “furniture”, through which the transmissions negotiate their way, is grounded in the structuralist linguistics of Zellig Harris and Charles Hockett. (In fact, the poems of his final book, Language, refer to linguistic concepts such as morphemes and graphemes). As such, Spicer is acknowledged as a precursor and early inspiration for the Language poets. However, many working poets today list Spicer in their succession of precedent figures. Spicer died as a result of his alcoholism. Since the posthumous publication of The Collected Books of Jack Spicer (first published in 1975), his popularity and influence has steadily risen, affecting poetry throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. In 1994, The Tower of Babel: Jack Spicer’s Detective Novel was published. Adding to the Jack Spicer revival was the publication in 1998 of two volumes: The House That Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer, edited by Peter Gizzi; and a biography: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance by Lewis Ellingham and Kevin Killian (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998). A collected works entitled My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer (Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian, editors) was published by Wesleyan University Press in November 2008, and won the American Book Award in 2009. A collection of critical essays entitled After Spicer: Critical Essays (John Emil Vincent, editor) was published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011. Further reading Blaser, Robin, editor. The Collected Books of Jack Spicer. Santa Rosa, Calif.: Black Sparrow Press, 1975 A Book Of Correspondences For Jack Spicer. Edited By David Levi Strauss and Benjamin Hollander. San Francisco: A Journal of Acts (#6), 1987; (Note: this is a collection of essays, poetry, and documents celebrating Spicer) Diaman, N. A.. Following My Heart: A Memoir. San Francisco: Persona Press, May 2007 _____. The City: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, August 2007 _____. Sitting With Jack At The Poets Table. Los Angeles: The Advocate, 1984 _____. Second Crossing: A Novel. San Francisco: Persona Press, 1982 Ellingham, Lewis, and Kevin Killian. Poet, Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Foster, Edward Halsey. Jack Spicer. Boise, Idaho: Boise State University, 1991 Gizzi, Peter, editor. The House that Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1998 Spicer, Jack. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part 1, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, introduction by David Hadbawnik, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 _____. Jack Spicer’s Beowulf, Part II, edited by David Hadbawnik & Sean Reynolds, afterword by Sean Reynolds, Lost and Found: The CUNY Poetics Documents Initiative, New York, 2011 Tallman, Warren. In the Midst. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1992 Herndon, James. Everything as Expected San Francisco, 1973 Vincent, John Emil, editor. After Spicer: Critical Essays. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2011 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Spicer

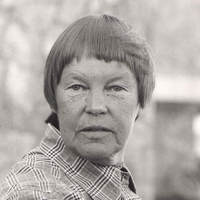

Marge Piercy (born March 31, 1936) is an American progressive activist, feminist, and writer. Her work includes Woman on the Edge of Time; He, She and It, which won the 1993 Arthur C. Clarke Award; and Gone to Soldiers, a New York Times Best Seller and a sweeping historical novel set during World War II. Piercy's work is rooted in her Jewish heritage, Communist social and political activism, and feminist ideals.

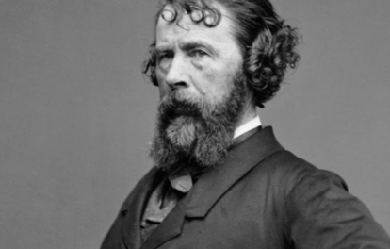

Henry David Thoreau (see name pronunciation; July 12, 1817– May 6, 1862) was an American author, poet, philosopher, abolitionist, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, and historian. A leading transcendentalist, Thoreau is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay Resistance to Civil Government (also known as Civil Disobedience), an argument for disobedience to an unjust state. Thoreau’s books, articles, essays, journals, and poetry total over 20 volumes. Among his lasting contributions are his writings on natural history and philosophy, where he anticipated the methods and findings of ecology and environmental history, two sources of modern-day environmentalism. His literary style interweaves close natural observation, personal experience, pointed rhetoric, symbolic meanings, and historical lore, while displaying a poetic sensibility, philosophical austerity, and “Yankee” love of practical detail. He was also deeply interested in the idea of survival in the face of hostile elements, historical change, and natural decay; at the same time he advocated abandoning waste and illusion in order to discover life’s true essential needs. He was a lifelong abolitionist, delivering lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips and defending abolitionist John Brown. Thoreau’s philosophy of civil disobedience later influenced the political thoughts and actions of such notable figures as Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Thoreau is sometimes cited as an anarchist. Though Civil Disobedience seems to call for improving rather than abolishing government—"I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government"—the direction of this improvement points toward anarchism: “'That government is best which governs not at all;' and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have.” Richard T. Drinnon reproaches Thoreau for his ambiguity when writing on governance, noting that Thoreau’s “sly satire, his liking for wide margins for his writing, and his fondness for paradox provided ammunition for widely divergent interpretations of 'Civil Disobedience’.” Name pronunciation and physical appearance Amos Bronson Alcott and Thoreau’s aunt each wrote that “Thoreau” is pronounced like the word “thorough” (pronounced THUR-oh—/ˈθʌroʊ/—in General American, but more precisely THOR-oh—/ˈθɔːroʊ/—in 19th-century New England). Edward Waldo Emerson wrote that the name should be pronounced “Thó-row”, with the h sounded and stress on the first syllable. Among modern-day American speakers, it is perhaps more commonly pronounced thə-ROH—/θəˈroʊ/—with stress on the second syllable. In appearance he was homely, with a nose that he called “my most prominent feature.” Of his face and disposition, Ellery Channing wrote: “His face, once seen, could not be forgotten. The features were quite marked: the nose aquiline or very Roman, like one of the portraits of Caesar (more like a beak, as was said); large overhanging brows above the deepest set blue eyes that could be seen, in certain lights, and in others gray,—eyes expressive of all shades of feeling, but never weak or near-sighted; the forehead not unusually broad or high, full of concentrated energy and purpose; the mouth with prominent lips, pursed up with meaning and thought when silent, and giving out when open with the most varied and unusual instructive sayings.” Life Early life and education, 1817–1836 Henry David Thoreau was born David Henry Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts, into the “modest New England family” of John Thoreau (a pencil maker) and Cynthia Dunbar. His paternal grandfather was born in Jersey. His maternal grandfather, Asa Dunbar, led Harvard’s 1766 student “Butter Rebellion”, the first recorded student protest in the Colonies. David Henry was named after a recently deceased paternal uncle, David Thoreau. He did not become “Henry David” until after college, although he never petitioned to make a legal name change. He had two older siblings, Helen and John Jr., and a younger sister, Sophia. Thoreau’s birthplace still exists on Virginia Road in Concord. The house has recently been restored by the Thoreau Farm Trust, a nonprofit organization, and is now open to the public. He studied at Harvard College between 1833 and 1837. He lived in Hollis Hall and took courses in rhetoric, classics, philosophy, mathematics, and science. He was a member of the Institute of 1770 (now the Hasty Pudding Club). A legend proposes that Thoreau refused to pay the five-dollar fee for a Harvard diploma. In fact, the master’s degree he declined to purchase had no academic merit: Harvard College offered it to graduates “who proved their physical worth by being alive three years after graduating, and their saving, earning, or inheriting quality or condition by having Five Dollars to give the college.” His comment was: “Let every sheep keep its own skin”, a reference to the tradition of diplomas being written on sheepskin vellum. Return to Concord, 1836–1842 The traditional professions open to college graduates—law, the church, business, medicine—failed to interest Thoreau, so in 1835 he took a leave of absence from Harvard, during which he taught school in Canton, Massachusetts. After he graduated in 1837, he joined the faculty of the Concord public school, but resigned after a few weeks rather than administer corporal punishment. He and his brother John then opened a grammar school in Concord in 1838 called Concord Academy. They introduced several progressive concepts, including nature walks and visits to local shops and businesses. The school ended when John became fatally ill from tetanus in 1842 after cutting himself while shaving. He died in his brother Henry’s arms. Upon graduation Thoreau returned home to Concord, where he met Ralph Waldo Emerson through a mutual friend. Emerson took a paternal and at times patronizing interest in Thoreau, advising the young man and introducing him to a circle of local writers and thinkers, including Ellery Channing, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne and his son Julian Hawthorne, who was a boy at the time. Emerson urged Thoreau to contribute essays and poems to a quarterly periodical, The Dial, and Emerson lobbied editor Margaret Fuller to publish those writings. Thoreau’s first essay published there was Aulus Persius Flaccus, an essay on the playwright of the same name, published in The Dial in July 1840. It consisted of revised passages from his journal, which he had begun keeping at Emerson’s suggestion. The first journal entry on October 22, 1837, reads, “'What are you doing now?' he asked. ‘Do you keep a journal?’ So I make my first entry to-day.” Thoreau was a philosopher of nature and its relation to the human condition. In his early years he followed Transcendentalism, a loose and eclectic idealist philosophy advocated by Emerson, Fuller, and Alcott. They held that an ideal spiritual state transcends, or goes beyond, the physical and empirical, and that one achieves that insight via personal intuition rather than religious doctrine. In their view, Nature is the outward sign of inward spirit, expressing the “radical correspondence of visible things and human thoughts”, as Emerson wrote in Nature (1836). On April 18, 1841, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house. There, from 1841–1844, he served as the children’s tutor, editorial assistant, and repair man/gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William Emerson on Staten Island, and tutored the family sons while seeking contacts among literary men and journalists in the city who might help publish his writings, including his future literary representative Horace Greeley. Thoreau returned to Concord and worked in his family’s pencil factory, which he continued to do for most of his adult life. He rediscovered the process to make a good pencil out of inferior graphite by using clay as the binder; this invention improved upon graphite found in New Hampshire and bought in 1821 by relative Charles Dunbar. (The process of mixing graphite and clay, known as the Conté process, was patented by Nicolas-Jacques Conté in 1795). His other source had been Tantiusques, an Indian operated mine in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. Later, Thoreau converted the factory to produce plumbago (graphite), which was used in the electrotyping process. Once back in Concord, Thoreau went through a restless period. In April 1844 he and his friend Edward Hoar accidentally set a fire that consumed 300 acres (1.2 km2) of Walden Woods. Civil Disobedience and the Walden years, 1845–1849 I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion. Thoreau needed to concentrate and get himself working more on his writing. In March 1845, Ellery Channing told Thoreau, "Go out upon that, build yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no other alternative, no other hope for you." Two months later, Thoreau embarked on a two-year experiment in simple living on July 4, 1845, when he moved to a small, self-built house on land owned by Emerson in a second-growth forest around the shores of Walden Pond. The house was in “a pretty pasture and woodlot” of 14 acres (57,000 m2) that Emerson had bought, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from his family home. On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local tax collector, Sam Staples, who asked him to pay six years of delinquent poll taxes. Thoreau refused because of his opposition to the Mexican–American War and slavery, and he spent a night in jail because of this refusal. The next day Thoreau was freed when someone, likely his aunt, paid the tax against his wishes. The experience had a strong impact on Thoreau. In January and February 1848, he delivered lectures on “The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government” explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Bronson Alcott attended the lecture, writing in his journal on January 26: Heard Thoreau’s lecture before the Lyceum on the relation of the individual to the State– an admirable statement of the rights of the individual to self-government, and an attentive audience. His allusions to the Mexican War, to Mr. Hoar’s expulsion from Carolina, his own imprisonment in Concord Jail for refusal to pay his tax, Mr. Hoar’s payment of mine when taken to prison for a similar refusal, were all pertinent, well considered, and reasoned. I took great pleasure in this deed of Thoreau’s. Thoreau revised the lecture into an essay entitled Resistance to Civil Government (also known as Civil Disobedience). In May 1849 it was published by Elizabeth Peabody in the Aesthetic Papers. Thoreau had taken up a version of Percy Shelley’s principle in the political poem The Mask of Anarchy (1819), that Shelley begins with the powerful images of the unjust forms of authority of his time—and then imagines the stirrings of a radically new form of social action. At Walden Pond, he completed a first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, an elegy to his brother, John, that described their 1839 trip to the White Mountains. Thoreau did not find a publisher for this book and instead printed 1,000 copies at his own expense, though fewer than 300 were sold. Thoreau self-published on the advice of Emerson, using Emerson’s own publisher, Munroe, who did little to publicize the book. In August 1846, Thoreau briefly left Walden to make a trip to Mount Katahdin in Maine, a journey later recorded in “Ktaadn”, the first part of The Maine Woods. Thoreau left Walden Pond on September 6, 1847. At Emerson’s request, he immediately moved back into the Emerson house to help Lidian manage the household while her husband was on an extended trip to Europe. Over several years, he worked to pay off his debts and also continuously revised his manuscript for what, in 1854, he would publish as Walden, or Life in the Woods, recounting the two years, two months, and two days he had spent at Walden Pond. The book compresses that time into a single calendar year, using the passage of four seasons to symbolize human development. Part memoir and part spiritual quest, Walden at first won few admirers, but later critics have regarded it as a classic American work that explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models for just social and cultural conditions. American poet Robert Frost wrote of Thoreau, “In one book... he surpasses everything we have had in America.” American author John Updike said of the book: “A century and a half after its publication, Walden has become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible.” Thoreau moved out of Emerson’s house in July 1848 and stayed at a home on Belknap Street nearby. In 1850, he and his family moved into a home at 255 Main Street; he stayed there until his death. Later years, 1851–1862 In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and travel/expedition narratives. He read avidly on botany and often wrote observations on this topic into his journal. He admired William Bartram, and Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle. He kept detailed observations on Concord’s nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds migrated. The point of this task was to “anticipate” the seasons of nature, in his words. He became a land surveyor and continued to write increasingly detailed natural history observations about the 26 square miles (67 km2) town in his journal, a two-million word document he kept for 24 years. He also kept a series of notebooks, and these observations became the source for Thoreau’s late natural history writings, such as Autumnal Tints, The Succession of Trees, and Wild Apples, an essay lamenting the destruction of indigenous and wild apple species. Until the 1970s, literary critics dismissed Thoreau’s late pursuits as amateur science and philosophy. With the rise of environmental history and ecocriticism, several new readings of this matter began to emerge, showing Thoreau to be both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in fields and woodlots. For instance, his late essay, “The Succession of Forest Trees”, shows that he used experimentation and analysis to explain how forests regenerate after fire or human destruction, through dispersal by seed-bearing winds or animals. He traveled to Quebec once, Cape Cod four times, and Maine three times; these landscapes inspired his “excursion” books, A Yankee in Canada, Cape Cod, and The Maine Woods, in which travel itineraries frame his thoughts about geography, history and philosophy. Other travels took him southwest to Philadelphia and New York City in 1854, and west across the Great Lakes region in 1861, visiting Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Mackinac Island. Although provincial in his physical travels, he was extraordinarily well-read. He obsessively devoured all the first-hand travel accounts available in his day, at a time when the last unmapped regions of the earth were being explored. He read Magellan and James Cook, the arctic explorers Franklin, Mackenzie and Parry, David Livingstone and Richard Francis Burton on Africa, Lewis and Clark; and hundreds of lesser-known works by explorers and literate travelers. Astonishing amounts of global reading fed his endless curiosity about the peoples, cultures, religions and natural history of the world, and left its traces as commentaries in his voluminous journals. He processed everything he read, in the local laboratory of his Concord experience. Among his famous aphorisms is his advice to “live at home like a traveler.” After John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, many prominent voices in the abolitionist movement distanced themselves from Brown, or damned him with faint praise. Thoreau was disgusted by this, and he composed a speech—A Plea for Captain John Brown—which was uncompromising in its defense of Brown and his actions. Thoreau’s speech proved persuasive: first the abolitionist movement began to accept Brown as a martyr, and by the time of the American Civil War entire armies of the North were literally singing Brown’s praises. As a contemporary biographer of John Brown put it: “If, as Alfred Kazin suggests, without John Brown there would have been no Civil War, we would add that without the Concord Transcendentalists, John Brown would have had little cultural impact.” Death Thoreau contracted tuberculosis in 1835 and suffered from it sporadically afterwards. In 1859, following a late-night excursion to count the rings of tree stumps during a rain storm, he became ill with bronchitis. His health declined over three years with brief periods of remission, until he eventually became bedridden. Recognizing the terminal nature of his disease, Thoreau spent his last years revising and editing his unpublished works, particularly The Maine Woods and Excursions, and petitioning publishers to print revised editions of A Week and Walden. He also wrote letters and journal entries until he became too weak to continue. His friends were alarmed at his diminished appearance and were fascinated by his tranquil acceptance of death. When his aunt Louisa asked him in his last weeks if he had made his peace with God, Thoreau responded: “I did not know we had ever quarreled.” Aware he was dying, Thoreau’s last words were “Now comes good sailing”, followed by two lone words, “moose” and “Indian”. He died on May 6, 1862 at age 44. Bronson Alcott planned the service and read selections from Thoreau’s works, and Channing presented a hymn. Emerson wrote the eulogy spoken at his funeral. Originally buried in the Dunbar family plot, he and members of his immediate family were eventually moved to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery (N42° 27' 53.7" W71° 20' 33") in Concord, Massachusetts. Thoreau’s friend Ellery Channing published his first biography, Thoreau the Poet-Naturalist, in 1873, and Channing and another friend Harrison Blake edited some poems, essays, and journal entries for posthumous publication in the 1890s. Thoreau’s journals, which he often mined for his published works but which remained largely unpublished at his death, were first published in 1906 and helped to build his modern reputation. A new, expanded edition of the journals is underway, published by Princeton University Press. Today, Thoreau is regarded as one of the foremost American writers, both for the modern clarity of his prose style and the prescience of his views on nature and politics. His memory is honored by the international Thoreau Society and his legacy honored by the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods, established in 1998 in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Nature and human existence Most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind. Thoreau was an early advocate of recreational hiking and canoeing, of conserving natural resources on private land, and of preserving wilderness as public land. He was not a strict vegetarian, though he said he preferred that diet and advocated it as a means of self-improvement. He wrote in Walden: “The practical objection to animal food in my case was its uncleanness; and besides, when I had caught and cleaned and cooked and eaten my fish, they seemed not to have fed me essentially. It was insignificant and unnecessary, and cost more than it came to. A little bread or a few potatoes would have done as well, with less trouble and filth.” Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead he sought a middle ground, the pastoral realm that integrates both nature and culture. His philosophy required that he be a didactic arbitration between the wilderness he based so much on and the spreading mass of North American humanity. He decried the latter endlessly but felt the teachers need to be close to those who needed to hear what he wanted to tell them. The wildness he enjoyed was the nearby swamp or forest, and he preferred “partially cultivated country.” His idea of being “far in the recesses of the wilderness” of Maine was to “travel the logger’s path and the Indian trail”, but he also hiked on pristine untouched land. In the essay “Henry David Thoreau, Philosopher” Roderick Nash writes: "Thoreau left Concord in 1846 for the first of three trips to northern Maine. His expectations were high because he hoped to find genuine, primeval America. But contact with real wilderness in Maine affected him far differently than had the idea of wilderness in Concord. Instead of coming out of the woods with a deepened appreciation of the wilds, Thoreau felt a greater respect for civilization and realized the necessity of balance." On alcohol, Thoreau wrote: “I would fain keep sober always... I believe that water is the only drink for a wise man; wine is not so noble a liquor... Of all ebriosity, who does not prefer to be intoxicated by the air he breathes?” Sexuality Thoreau strove to portray himself as an ascetic puritan. However, his sexuality has long been the subject of speculation, including by his contemporaries. Critics have called him heterosexual, homosexual, or asexual. There is no evidence to suggest he had physical relations with anyone, man or woman. Some scholars suggest that homoerotic sentiments run through his writings, and conclude that he was homosexual. The elegy Sympathy was inspired by the eleven-year-old Edmund Sewell, with whom he hiked for five days in 1839. One scholar has suggested that he wrote the poem to Edmund because he could not bring himself to write it to Edmund’s sister, and another that Thoreau’s “emotional experiences with women are memorialized under a camouflage of masculine pronouns”, but other scholars dismiss this. It has argued that the long paean in Walden to the French-Canadian woodchopper Alek Therien, which includes allusions to Achilles and Patroclus, is an expression of conflicted desire. In some of Thoreau’s writing there is the sense of a secret self. In 1840 he writes in his journal: “My friend is the apology for my life. In him are the spaces which my orbit traverses”. Thoreau was strongly influenced by the moral reformers of his time, and this may have instilled anxiety and guilt over sexual desire. Politics Thoreau was fervently against slavery and actively supported the abolitionist movement. He participated in the Underground Railroad, delivered lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law, and in opposition with the popular opinion of the time, supported radical abolitionist militia leader John Brown and his party. Two weeks after the ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry and in the weeks leading up to Brown’s execution, Thoreau regularly delivered a speech to the citizens of Concord, Massachusetts in which he compared the American government to Pontius Pilate and likened Brown’s execution to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ: “Some eighteen hundred years ago Christ was crucified; this morning, perchance, Captain Brown was hung. These are the two ends of a chain which is not without its links. He is not Old Brown any longer; he is an angel of light.” In The Last Days of John Brown, Thoreau described the words and deeds of John Brown as noble and an example of heroism. In addition, he lamented the newspaper editors who dismissed Brown and his scheme as “crazy”. Thoreau was a proponent of limited government and individualism. Although he was hopeful that mankind could potentially have, through self-betterment, the kind of government which “governs not at all”, he distanced himself from contemporary “no-government men” (anarchists), writing: “I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government.” Thoreau deemed the evolution from absolute monarchy to limited monarchy to democracy as “a progress toward true respect for the individual” and theorized about further improvements “towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man.” Echoing this belief, he went on to write: “There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly.” Although Thoreau believed resistance to unjustly exercised authority could be both violent (exemplified in his support for John Brown) and nonviolent (his own example of tax resistance displayed in Resistance to Civil Government), he regarded pacifist nonresistance as temptation to passivity, writing: “Let not our Peace be proclaimed by the rust on our swords, or our inability to draw them from their scabbards; but let her at least have so much work on her hands as to keep those swords bright and sharp.” Furthermore, in a formal lyceum debate in 1841, he debated the subject “Is it ever proper to offer forcible resistance?”, arguing the affirmative. Likewise, his condemnation of the Mexican–American War did not stem from pacifism, but rather because he considered Mexico “unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army” as a means to expand the slave territory. Thoreau was ambivalent towards industrialization and capitalism. On one hand he regarded commerce as “unexpectedly confident and serene, adventurous, and unwearied” and expressed admiration for its associated cosmopolitanism, writing: I am refreshed and expanded when the freight train rattles past me, and I smell the stores which go dispensing their odors all the way from Long Wharf to Lake Champlain, reminding me of foreign parts, of coral reefs, and Indian oceans, and tropical climes, and the extent of the globe. I feel more like a citizen of the world at the sight of the palm-leaf which will cover so many flaxen New England heads the next summer. On the other hand, he wrote disparagingly of the factory system: I cannot believe that our factory system is the best mode by which men may get clothing. The condition of the operatives is becoming every day more like that of the English; and it cannot be wondered at, since, as far as I have heard or observed, the principal object is, not that mankind may be well and honestly clad, but, unquestionably, that corporations may be enriched. Thoreau also favored bioregionalism, the protection of animals and wild areas, free trade, and taxation for schools and highways. He disapproved of the subjugation of Native Americans, slavery, technological utopianism, consumerism, philistinism, mass entertainment, and frivolous applications of technology. Intellectual interests, influences, and affinities Indian sacred texts and philosophy Thoreau was influenced by Indian spiritual thought. In Walden, there are many overt references to the sacred texts of India. For example, in the first chapter ("Economy"), he writes: “How much more admirable the Bhagvat-Geeta than all the ruins of the East!” American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia classes him as one of several figures who “took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world”, also a characteristic of Hinduism. Furthermore, in “The Pond in Winter”, he equates Walden Pond with the sacred Ganges river, writing: In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat Geeta since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahmaand Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges. Additionally, Thoreau followed various Hindu customs, including following a diet of rice ("It was fit that I should live on rice, mainly, who loved so well the philosophy of India."), flute playing (reminiscent of the favorite musical pastime of Krishna), and yoga. In an 1849 letter to his friend H.G.O. Blake, he wrote about yoga and its meaning to him: Free in this world as the birds in the air, disengaged from every kind of chains, those who practice yoga gather in Brahma the certain fruits of their works. Depend upon it that, rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. The yogi, absorbed in contemplation, contributes in his degree to creation; he breathes a divine perfume, he hears wonderful things. Divine forms traverse him without tearing him, and united to the nature which is proper to him, he goes, he acts as animating original matter. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a yogi. Biology Thoreau read contemporary works in the new science of biology, including the works of Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Darwin, and Asa Gray (Charles Darwin’s staunchest American ally). Thoreau was deeply influenced by Humboldt, especially his work Kosmos. In 1859, Thoreau purchased and read Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Unlike many natural historians at the time, including Louis Agassiz who publicly opposed Darwinism in favor of a static view of nature, Thoreau was immediately enthusiastic about the theory of evolution by natural selection and endorsed it, stating: The development theory implies a greater vital force in Nature, because it is more flexible and accommodating, and equivalent to a sort of constant new creation. (A quote from On the Origin of Species follows this sentence.) Influence “Thoreau’s careful observations and devastating conclusions have rippled into time, becoming stronger as the weaknesses Thoreau noted have become more pronounced... Events that seem to be completely unrelated to his stay at Walden Pond have been influenced by it, including the national park system, the British labor movement, the creation of India, the civil rights movement, the hippie revolution, the environmental movement, and the wilderness movement. Today, Thoreau’s words are quoted with feeling by liberals, socialists, anarchists, libertarians, and conservatives alike.” Thoreau’s political writings had little impact during his lifetime, as "his contemporaries did not see him as a theorist or as a radical, viewing him instead as a naturalist. They either dismissed or ignored his political essays, including Civil Disobedience. The only two complete books (as opposed to essays) published in his lifetime, Walden and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849), both dealt with nature, in which he loved to wander." His obituary was lumped in with others rather than as a separate article in an 1862 yearbook. Nevertheless, Thoreau’s writings went on to influence many public figures. Political leaders and reformers like Mohandas Gandhi, U.S. President John F. Kennedy, American civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, and Russian author Leo Tolstoy all spoke of being strongly affected by Thoreau’s work, particularly Civil Disobedience, as did "right-wing theorist Frank Chodorov [who] devoted an entire issue of his monthly, Analysis, to an appreciation of Thoreau.” Thoreau also influenced many artists and authors including Edward Abbey, Willa Cather, Marcel Proust, William Butler Yeats, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, E. B. White, Lewis Mumford, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alexander Posey and Gustav Stickley. Thoreau also influenced naturalists like John Burroughs, John Muir, E. O. Wilson, Edwin Way Teale, Joseph Wood Krutch, B. F. Skinner, David Brower and Loren Eiseley, whom Publishers Weekly called “the modern Thoreau.” English writer Henry Stephens Salt wrote a biography of Thoreau in 1890, which popularized Thoreau’s ideas in Britain: George Bernard Shaw, Edward Carpenter and Robert Blatchford were among those who became Thoreau enthusiasts as a result of Salt’s advocacy. Mohandas Gandhi first read Walden in 1906 while working as a civil rights activist in Johannesburg, South Africa. He first read Civil Disobedience “while he sat in a South African prison for the crime of nonviolently protesting discrimination against the Indian population in the Transvaal. The essay galvanized Gandhi, who wrote and published a synopsis of Thoreau’s argument, calling its 'incisive logic... unanswerable’ and referring to Thoreau as 'one of the greatest and most moral men America has produced’.” He told American reporter Webb Miller, "[Thoreau’s] ideas influenced me greatly. I adopted some of them and recommended the study of Thoreau to all of my friends who were helping me in the cause of Indian Independence. Why I actually took the name of my movement from Thoreau’s essay ‘On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,’ written about 80 years ago.” Martin Luther King, Jr. noted in his autobiography that his first encounter with the idea of nonviolent resistance was reading “On Civil Disobedience” in 1944 while attending Morehouse College. He wrote in his autobiography that it was, “Here, in this courageous New Englander’s refusal to pay his taxes and his choice of jail rather than support a war that would spread slavery’s territory into Mexico, I made my first contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance. Fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system, I was so deeply moved that I reread the work several times. I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of a legacy of creative protest. The teachings of Thoreau came alive in our civil rights movement; indeed, they are more alive than ever before. Whether expressed in a sit-in at lunch counters, a freedom ride into Mississippi, a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, these are outgrowths of Thoreau’s insistence that evil must be resisted and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice.” American psychologist B. F. Skinner wrote that he carried a copy of Thoreau’s Walden with him in his youth. and, in 1945, wrote Walden Two, a fictional utopia about 1,000 members of a community living together inspired by the life of Thoreau. Thoreau and his fellow Transcendentalists from Concord were a major inspiration of the composer Charles Ives. The 4th movement of the Concord Sonata for piano (with a part for flute, Thoreau’s instrument) is a character picture and he also set Thoreau’s words. In the early 1960s Allan Sherman referred to Thoreau in his song parody “Here’s To Crabgrass” about the suburban housing boom of that era with the line “Come let us go there and live like Thoreau there.” Actor Ron Thompson did a dramatic portrayal of Henry David Thoreau on the 1976 NBC television series The Rebels. Thoreau’s ideas have impacted and resonated with various strains in the anarchist movement, with Emma Goldman referring to him as “the greatest American anarchist.” Green anarchism and Anarcho-primitivism in particular have both derived inspiration and ecological points-of-view from the writings of Thoreau. John Zerzan included Thoreau’s text “Excursions” (1863) in his edited compilation of works in the anarcho-primitivist tradition titled Against civilization: Readings and reflections. Additionally, Murray Rothbard, the founder of anarcho-capitalism, has opined that Thoreau was one of the “great intellectual heroes” of his movement. Thoreau was also an important influence on late-19th-century anarchist naturism. Globally, Thoreau’s concepts also held importance within individualist anarchist circles in Spain, France, and Portugal. Criticism Although his writings would receive widespread acclaim, Thoreau’s ideas were not universally applauded. Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson judged Thoreau’s endorsement of living alone and apart from modern society in natural simplicity to be a mark of “unmanly” effeminacy and “womanish solitude”, while deeming him a self-indulgent “skulker.” Nathaniel Hawthorne was also critical of Thoreau, writing that he “repudiated all regular modes of getting a living, and seems inclined to lead a sort of Indian life among civilized men.” In a similar vein, poet John Greenleaf Whittier detested what he deemed to be the “wicked” and “heathenish” message of Walden, claiming that Thoreau wanted man to “lower himself to the level of a woodchuck and walk on four legs.” In response to such criticisms, English novelist George Eliot, writing for the Westminster Review, characterized such critics as uninspired and narrow-minded: People—very wise in their own eyes—who would have every man’s life ordered according to a particular pattern, and who are intolerant of every existence the utility of which is not palpable to them, may pooh-pooh Mr. Thoreau and this episode in his history, as unpractical and dreamy. Thoreau himself also responded to the criticism in a paragraph of his work “Walden” (1854), by illustrating the irrelevance of their inquiries: I should not obtrude my affairs so much on the notice of my readers if very particular inquiries had not been made by my townsmen concerning my mode of life, which some would call impertinent, though they do not appear to me at all impertinent, but, considering the circumstances, very natural and pertinent. Some have asked what I got to eat; if I did not feel lonesome; if I was not afraid; and the like. Others have been curious to learn what portion of my income I devoted to charitable purposes; and some, who have large families, how many poor children I maintained. [...] Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience. Moreover, I, on my side, require of every writer, first or last, a simple and sincere account of his own life, and not merely what he has heard of other men’s lives; [...] I trust that none will stretch the seams in putting on the coat, for it may do good service to him whom it fits. Recent criticism has accused Thoreau of hypocrisy, misanthropy and being sanctimonious, based on his writings in Walden, although this criticism has been perceived as highly selective. Works * Aulus Persius Flaccus (1840) * The Service (1840) * A Walk to Wachusett (1842) * Paradise (to be) Regained (1843) * The Landlord (1843) * Sir Walter Raleigh (1844) * Herald of Freedom (1844) * Wendell Phillips Before the Concord Lyceum (1845) * Reform and the Reformers (1846–48) * Thomas Carlyle and His Works (1847) * A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) * Resistance to Civil Government, or Civil Disobedience, or On the Duty of Civil Disobedience (1849) * An Excursion to Canada (1853) * Slavery in Massachusetts (1854) * Walden (1854) A Fully Annotated Edition. Jeffrey S. Cramer, ed., Yale University Press, 2004 * A Plea for Captain John Brown (1859) * Remarks After the Hanging of John Brown (1859) * The Last Days of John Brown (1860) * Walking (1861) * Autumnal Tints (1862) * Wild Apples: The History of the Apple Tree (1862) * The Fall of the Leaf (1863) * Excursions (1863) * Life Without Principle (1863) * Night and Moonlight (1863) * The Highland Light (1864) * The Maine Woods (1864) Fully Annotated Edition. Jeffrey S. Cramer, ed., Yale University Press, 2009 * Cape Cod (1865) * Letters to Various Persons (1865) * A Yankee in Canada, with Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers (1866) * Early Spring in Massachusetts (1881) * Summer (1884) * Winter (1888) * Autumn (1892) * Miscellanies (1894) * Familiar Letters of Henry David Thoreau (1894) * Poems of Nature (1895) * Some Unpublished Letters of Henry D. and Sophia E. Thoreau (1898) * The First and Last Journeys of Thoreau (1905) * Journal of Henry David Thoreau (1906) * The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau edited by Walter Harding and Carl Bode (Washington Square: New York University Press, 1958) * Poets of the English Language (Viking Press, 1950) * I Was Made Erect and Lone * The Bluebird Carries the Sky on His Back (Stanyan, 1970) * The Dispersion of Seeds (1993) * The Indian Notebooks (1847-1861) selections by Richard F. Fleck References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_David_Thoreau

Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth (December 22, 1905– June 6, 1982) was an American poet, translator and critical essayist. He is regarded as a central figure in the San Francisco Renaissance, and paved the groundwork for the movement. Although he did not consider himself to be a Beat poet, and disliked the association, he was dubbed the “Father of the Beats” by Time Magazine. He was among the first poets in the United States to explore traditional Japanese poetic forms such as haiku. He was also a prolific reader of Chinese literature.

Lisel Mueller was born in Hamburg, Germany, on February 8, 1924 and immigrated to America at the age of 15. She won the U.S. National Book Award in 1981 and the Pulitzer Prize in 1997. Her poems are extremely accessible, yet intricate and layered. While at times whimsical and possessing a sly humor, there is an underlying sadness in much of her work.

Arthur Yvor Winters (17 October 1900– 25 January 1968) was an American poet and literary critic. Life Winters was born in Chicago, Illinois and he grew up in Eagle Rock, California. He attended the University of Chicago where he was a member of a literary circle that included Glenway Wescott, Elizabeth Madox Roberts and his future wife Janet Lewis. He suffered from tuberculosis in his late teens and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. There he recuperated, wrote his early published verse and taught. In 1923 Winters published one of his first critical essays, “Notes on the Mechanics of the Poetic Image,” in the expatriate literary journal Secession. In 1925 he became an undergraduate at the University of Colorado. In 1926, Winters married the poet and novelist Janet Lewis, also from Chicago and a tuberculosis sufferer. After graduating he taught at the University of Idaho and then started a doctorate at Stanford University. He remained at Stanford, living in Los Altos, until two years before his death from throat cancer. His students included the poets Edgar Bowers, Thom Gunn, Donald Hall, Jim McMichael, N. Scott Momaday, Robert Pinsky, John Matthias, Moore Moran, Roger Dickinson-Brown and Robert Hass, the critic Gerald Graff, and the theater director and writer Herbert Blau. He was also a mentor to Donald Justice, J.V. Cunningham and Bunichi Kagawa. He edited the literary magazine Gyroscope with his wife from 1929 to 1931; and Hound & Horn from 1932 to 1934. He was awarded the 1961 Bollingen Prize for Poetry for his Collected Poems. As modernist Winters’s early poetry appeared in small avant-garde magazines alongside work by writers like James Joyce and Gertrude Stein and was written in the modernist idiom; it was heavily influenced both by Native American poetry and by Imagism, being described as 'arriving late at the Imagist feast’. His essay, “The Testament of a Stone,” gives an account of his poetics during this early period. Although beginning his career as an admirer and imitator of the Imagist poets, Winters by the end of the 1920s had formulated a neo-classic poetics. Around 1930, he turned away from modernism and developed an Augustan style of writing, notable for its clarity of statement and its formality of rhyme and rhythm, with most of his poetry thereafter being in the accentual-syllabic form. As critic Winters’s critical style was comparable to that of F. R. Leavis, and in the same way he created a school of students (of mixed loyalty). His affiliations and proposed canon, however, were quite different: Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence above any one novel by Henry James, Robert Bridges above T. S. Eliot, Charles Churchill above Alexander Pope, Fulke Greville and George Gascoigne above Sidney and Spenser. In his view, “a poem in the first place should offer us a new perception . . . bringing into being a new experience.” He attacked Romanticism, particularly in its American manifestations, and assailed Emerson’s reputation as that of a sacred cow. Ironically, his first book of poems, Diadems and Fagots, takes its title from one of Emerson’s poems. In this he was probably influenced by Irving Babbitt. Winters was sometimes and questionably associated with the New Criticism, largely because John Crowe Ransom devoted a chapter to him in his book of the same name. He bestowed the sobriquet “the cool master” on the American poet Wallace Stevens. Winters is best known for his argument attacking the “fallacy of imitative form”: “To say that a poet is justified in employing a disintegrating form in order to express a feeling of disintegration, is merely a sophistical justification for bad poetry, akin to the Whitmanian notion that one must write loose and sprawling poetry to 'express’ the loose and sprawling American continent. In fact, all feeling, if one gives oneself (that is, one’s form) up to it, is a way of disintegration; poetic form is by definition a means to arrest the disintegration and order the feeling; and in so far as any poetry tends toward the formless, it fails to be expressive of anything.” Bibliography * Diadems and Fagots (1921) poems * The Immobile Wind (1921) poems * The Magpie’s Shadow (1922) poems * Secession certain Notes on the Mechanics of the Image (1923) a magazine * The Bare Hills (1927) poems * The Proof (1930) poems * The Journey and Other Poems (1931) poems * Before Disaster (1934) poems * Primitivism and Decadence: A Study of American Experimental Poetry Arrow Editions, New York, 1937 * Maule’s Curse: Seven Studies in the History of American Obscurantism (1938) * Poems (1940) * The Giant Weapon (1943) poems * The Anatomy of Nonsense (1943) * Edwin Arlington Robinson (1946) * In Defense of Reason (1947) collects Primitivism, Maule and Anatomy * To the Holy Spirit (1947) poems * Three Poems (1950) * Collected Poems (1952, revised 1960) * The Function of Criticism: Problems and Exercises (1957) * On Modern Poets: Stevens, Eliot, Ransom, Crane, Hopkins, Frost (1959) * The Early Poems of Yvor Winters, 1920–1928 (1966) * Forms of Discovery: Critical and Historical Essays on the Forms of the Short Poem in English (1967) * Uncollected Essays and Reviews (1976) * The Collected Poems of Yvor Winters; with an introduction by Donald Davie (1978) * Uncollected Poems 1919–1928 (1997) * Uncollected Poems 1929–1957 (1997) * Yvor Winters: Selected Poems (2003) edited by Thom Gunn * As editor * Twelve Poets of the Pacific (1937) * Selected Poems, by Elizabeth Daryush (1948); with a foreword by Winters * Poets of the Pacific, Second Series (1949) * Quest for Reality: An Anthology of Short Poems in English (1969); with, and with an introduction by, Kenneth Fields References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yvor_Winters

Louis Untermeyer (October 1, 1885 – December 18, 1977) was an American poet, anthologist, critic, and editor. He was appointed the fourteenth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1961. Untermeyer was born in New York City. He married Jean Starr in 1906. Their son Richard was born in 1907 and died under uncertain circumstances in 1927. After a 1926 divorce, they were reunited in 1929, after which they adopted two sons, Laurence and Joseph. He married the poet Virginia Moore in 1927; their son, John Moore Untermeyer (1928), was renamed John Fitzallen Moore after a painful 1929 divorce. In the 1930s, he divorced Jean Starr Untermeyer and married Esther Antin. This relationship also ended in divorce in 1945. In 1948, he married Bryna Ivens, an editor of Seventeen magazine. Untermeyer was known for his wit and his love of puns. For a while, he held Marxist beliefs, writing for magazines such as The Masses, through which he advocated that the United States stay out of World War I. After the suppression of that magazine by the U.S. government, he joined The Liberator, published by the Workers Party of America. Later he wrote for the independent socialist magazine The New Masses. He was a co-founder of "The Seven Arts," a poetry magazine that is credited for introducing many new poets, including Robert Frost, who became Untermeyer's long-term friend and correspondent. In 1950, Untermeyer was a panelist during the first year of the What's My Line? television quiz program. According to Bennett Cerf, Untermeyer would sign virtually any piece of paper that someone placed in front of him, and Untermeyer inadvertently signed a few Communist proclamations. According to Cerf, Untermeyer was not at all a communist, but he had joined several suspect societies that made him stand out. He was named during the hearings by the House Committee on Un-American Activities investigating communist subversion. The Catholic War Veterans and "right wing organizations" began hounding Mr. Untermeyer. Goodson-Todman, producer of the show, held out against the protests of Untermeyer for some time, but finally war veterans began picketing outside the New York City television studio from which What's My Line? was telecast live. The pressure became too great, and the sponsor Jules Montenier, inventor of Stopette deodorant, said, “After all, I'm paying a lot of money for this. I can't afford to have my product picketed.” At that point, the producers told Untermeyer that he had to leave the television series. The last live telecast on which he appeared was on March 11, 1951, and the mystery guest he questioned while blindfolded was Celeste Holm. The kinescope of this episode has been lost. His exit led to Bennett Cerf becoming a permanent member of the program. The controversy surrounding Untermeyer led to him being blacklisted by the television industry. According to Untermeyer's friend Arthur Miller, Untermeyer became so depressed by his forced departure from What's My Line? that he refused to leave his home in Brooklyn for more than a year, and his wife Bryna answered all incoming phone calls. It was she who eventually told Miller what had happened because Untermeyer would not pick up the phone to talk to him, even though Miller's support of blacklisted writers and radio and television personalities was well-known to Untermeyer and many others. But for more than a year, whenever Miller dialed the Untermeyers' phone number, Bryna "talked obscurely about [her husband Louis] not wanting phone conversations anymore, preferring to wait until we could all get together again," wrote Miller. Miller was a "very infrequent television watcher" in 1951, according to words he used in his 1987 autobiography, and so he did not notice that Bennett Cerf had replaced Untermeyer on the live TV game show. Miller did read New York City newspapers every day, but apparently there was no published report of Untermeyer's disappearance from television, therefore Miller was unaware that anything was wrong until Untermeyer's wife Bryna revealed what it was eventually after they had conversed by phone for more than a year. Louis Untermeyer was the author or editor of close to 100 books, from 1911 until his death. Many of them and his other memorabilia are preserved in a special section of the Lilly Library at Indiana University. Schools used his Modern American and British poetry books widely, and they often introduced college students to poetry. He and Bryna Ivens Untermeyer created a number of books for young people, under the Golden Treasury of Children's Literature. Utermeyer also rounded up contributors for a Modern Masters for Children series published by Crowell-Collier Press in the 1960s--the books were designed to have a vocabulary of 800 words and contributors included Robert Graves, Phylis McGinley, and Shirley Jackson. He lectured on literature for many years, both in the US and other countries. In 1956 the Poetry Society of America awarded Untermeyer a Gold Medal. He also served as the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1961 until 1963. Poetry collections * The Younger Quire (parodies), Mood Publishing, 1911. * First Love, French, 1911. * Challenge, Century, 1914. * These Times, Holt, 1917. * Including Horace, Harcourt, 1919. * The New Adam, Harcourt, 1920. * Roast Leviathan, Harcourt, 1923, reprinted, Arno, 1975. * (With son, Richard Untermeyer) Poems, privately printed, 1927. * Burning Bush, Harcourt, 1928. * Adirondack Cycle, Random House, 1929. * Food and Drink, Harcourt, 1932. * First Words before Spring, Knopf, 1933. * Selected Poems and Parodies, Harcourt, 1935. * For You with Love (juvenile), Golden Press, 1961. * Long Feud: Selected Poems, Harcourt, 1962. * One and One and One (juvenile), Crowell-Collier, 1962. * This Is Your Day (juvenile), Golden Press, 1964. * Labyrinth of Love, Simon & Schuster, 1965. * Thanks: A Poem (juvenile), Odyssey, 1965. * Thinking of You (juvenile), Golden Press, 1968. * A Friend Indeed, Golden Press, 1968. * You: A Poem, (juvenile), illustrations by Martha Alexander, Golden Press, 1969. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Untermeyer

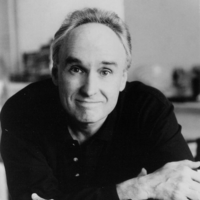

James Vincent Tate (December 8, 1943– July 8, 2015) was an American poet whose work earned him the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He was a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Biography Tate was born in Kansas City, Missouri, where he lived with his mother and his grandparents in his grandparents’ house. His father, a pilot in World War II, had died in combat on April 11, 1944, before Tate was a year old. Tate and his mother moved out after seven years when she remarried. The eventual poet said he belonged to a gang in high school and had little interest in literature. He planned on being a gas station attendant as his uncle had been, but finding that his friends to his surprise were going to college, he applied to Kansas State College of Pittsburg (now Pittsburg State University) in 1961. Tate wrote his first poem a few months into college with no external motivation; he observed that poetry “became a private place that I was hugely drawn to, where I could let my daydreams—and my pain—come in completely disguised. I knew from the moment I started writing that I never wanted to be writing about my life.” In college he read Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams and was “in heaven”. He received his B.A. in 1965, going on to earn his M.F.A. from the University of Iowa’s famed Writer’s Workshop. During this period he was finally exposed to fellow poets and he became interested in surrealism, reading Max Jacob, Robert Desnos, and André Breton; for Benjamin Péret he expressed particular affection. Of poets writing in Spanish, César Vallejo “destroyed” him but he was not so taken by the lyricism or romanticism of Pablo Neruda or Federico García Lorca. He was married to Dara Wier. Tate died on July 8, 2015 at the age of 71. Career Tate taught creative writing at the University of California, Berkeley, Columbia University, and at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he worked from 1971 until his death in 2015. He was a member of the poetry faculty at the MFA Program for Poets & Writers, along with Dara Wier and Peter Gizzi. Dudley Fitts selected Tate’s first book of poems, The Lost Pilot (1967), for the Yale Series of Younger Poets while Tate was still a student at the Writers’ Workshop; Fitts praised Tate’s writing for its “natural grace.” Tate’s first volume of poetry, Cages, was published by Shepherd’s Press, Iowa City, 1966. Tate won the 1992 Pulitzer Prize and the Poetry Society of America’s William Carlos Williams Award in 1991 for his Selected Poems. In 1994, he won the National Book Award for his poetry collection Worshipful Company of Fletchers. Tate’s writing style is often described as surrealistic, comic and absurdist. His work has captivated other poets as diverse as John Ashbery and Dana Gioia. Regarding his own work, Tate said, “My characters usually are—or, I’d say most often, I don’t want to generalize too much—but most often they’re in trouble, and they’re trying to find some kind of life.” This view is supported by the poet Tony Hoagland’s observation that “his work of late has been in prose poems, in which his picaresque speaker or characters are spinning through life, inquisitive and clueless as Candide, trying to identify and get with the fiction of whatever world they are in.” In addition to many books of poetry, he published two books of prose, Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee (2001) and The Route as Briefed (1999). Some of Tate’s additional awards included a National Institute of Arts and Letters Award, the Wallace Stevens Award, and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. He was also a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Published works Full-length poetry collections Dome of the Hidden Pavilion (Ecco Press, 2015) The Eternal Ones of the Dream: Selected Poems 1990-2010 (Ecco Press, 2012) The Ghost Soldiers (Ecco Press, 2008) Return to the City of White Donkeys (Ecco Press, 2004) Memoir of the Hawk (Ecco Press, 2002) Shroud of the Gnome (Ecco Press, 1997) Worshipful Company of Fletchers: Poems (Ecco Press, 1994)—winner of the National Book Award Selected Poems (Wesleyan University Press, 1991)—winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the William Carlos Williams Award Distance from Loved Ones (Wesleyan University Press, 1990) Reckoner (Wesleyan University Press, 1986) Constant Defender (Ecco Press, 1983) Riven Doggeries (Ecco Press, 1979) Viper Jazz (Wesleyan University Press, 1976) Absences: New Poems (Little, Brown & Co., 1972) Hints to Pilgrims (Halty Ferguson, 1971) The Oblivion Ha-Ha (Little, Brown & Co., 1970) The Lost Pilot (Yale University Press, 1967) Chapbooks The Zoo Club (Rain Taxi, 2011) Lost River (Sarabande Books, 2003) Police Story (Rain Taxi, 1999) Bewitched: 26 poems (Embers Handpress, Wales, illustration by Laurie Smith.) Just Shades (Parallel Editions, 1985, illustrated by John Alcorn) Land of Little Sticks (Metacom Press, 1981) Apology for Eating Geoffrey Movius’ Hyacinth (Unicorn Press, 1972) Amnesia People (Little Balkans Press, 1970) Wrong Songs (H. Ferguson, 1970) Shepherds of the Mist (Black Sparrow Press, 1969) The Torches (Unicorn Press, 1968) Prose Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee: 44 Stories (Verse Press, 2002) The Route as Briefed (University of Michigan Press, 1999) Hottentot Ossuary (Temple Bar Bookshop, 1974) Collaborations Lucky Darryl (Release Press, 1977, a novel co-written with Bill Knott) Are You Ready, Mary Baker Eddy??? (Cloud Marauder Press, 1970, poems co-written with Bill Knott) In anthologies Tate’s work has been included in The Best American Poetry series numerous times, including in 2010, 2008, 2006, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2001, 1998, 1997, 1994, 1993, 1991, 1990, and 1988; his work was also in the The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry. Honors and awards Tate was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2004; other recognition includes: Pulitzer Prize for Poetry National Institute of Arts and Letters Award Guggenheim Fellowship National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship in Poetry National Book Award for Poetry 1995 Wallace Stevens Award Yale Series of Younger Poets References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Tate_(writer)

Archie Randolph Ammons (February 18, 1926– February 25, 2001) was an American poet who won the annual National Book Award for Poetry in 1973 and 1993. Preface Ammons wrote about humanity’s relationship to nature in alternately comic and solemn tones. His poetry often addresses religious and philosophical matters and scenes involving nature, almost in a Transcendental fashion. According to reviewer Daniel Hoffman, his work “is founded on an implied Emersonian division of experience into Nature and the Soul,” adding that it "sometimes consciously echo[es] familiar lines from Emerson, Whitman and [Emily] Dickinson.” Life Ammons grew up on a tobacco farm near Whiteville, North Carolina, in the southeastern part of the state. He served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, stationed on board the U.S.S. Gunason, a battleship escort. After the war, Ammons attended Wake Forest University, majoring in biology. Graduating in 1949, he served as a principal and teacher at Hattaras Elementary School later that year and also married Phyllis Plumbo. He received an M.A. in English from the University of California, Berkeley. In 1964, Ammons joined the faculty of Cornell University, eventually becoming Goldwin Smith Professor of English and Poet in Residence. He retired from Cornell in 1998. Ammons had been a longtime resident of the South Jersey communities of Northfield, Ocean City and Millville, when he wrote Corsons Inlet in 1962. Awards * During the five decades of his poetic career, Ammons was the recipient of many awards and citations. Among his major honors are the 1973 and 1993 U.S. National Book Awards (for Collected Poems, 1951-1971 and for Garbage); the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets (1998); and a MacArthur Fellowship in 1981, the year the award was established. A school in Miami, Florida, was named after him. * Ammons’s other awards include a 1981 National Book Critics Circle Award for A Coast of Trees; a 1993 Library of Congress Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry for Garbage; the 1971 Bollingen Prize for Sphere; the Poetry Society of America’s Robert Frost Medal; the Ruth Lilly Prize; and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1978. Poetic style * Ammons often writes in two– or three-line stanzas. Poet David Lehman notes a resemblance between Ammons’s terza libre (unrhymed three-line stanzas) and the terza rima of Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind.” Lines are strongly enjambed. * Some of Ammons’s poems are very short, one or two lines only, a form known as monostich (effectively, including the title, a kind of couplet), while others (for example, the book-length poems Sphere and Tape for the Turn of the Year) are hundreds of lines long, and sometimes composed on adding-machine tape or other continuous strips of paper. His National Book Award-winning volume Garbage is a long poem consisting of “a single extended sentence, divided into eighteen sections, arranged in couplets”. Ammons’s long poems tend to derive multiple strands from a single image. * Many readers and critics have noted Ammons’s idiosyncratic approach to punctuation. Lehman has written that Ammons “bears out T. S. Eliot’s observation that poetry is a 'system of punctuation’.” Instead of periods, some poems end with an ellipsis; others have no terminal punctuation at all. The colon is an Ammons “signature”; he uses it “as an all-purpose punctuation mark.” * The colon permits him to stress the linkage between clauses and to postpone closure indefinitely.... When I asked Archie about his use of colons, he said that when he started writing poetry, he couldn’t write if he thought “it was going to be important,” so he wrote "on the back of used mimeographed paper my wife brought home, and I used small [lowercase] letters and colons, which were democratic, and meant that there would be something before and after [every phrase] and the writing would be a kind of continuous stream." * According to critic Stephen Burt, in many poems Ammons combines three types of diction: * A “normal” range of language for poetry, including the standard English of educated conversation and the slightly rarer words we expect to see in literature (“vast,” “summon,” “universal”). * A demotic register, including the folk-speech of eastern North Carolina, where he grew up (“dibbles”), and broader American chatter unexpected in serious poems (“blip”). * The Greek– and Latin-derived phraseology of the natural sciences (“millimeter,” “information of actions / summarized”), especially geology, physics, and cybernetics. * Such a mixture is nearly unique, Burt says; these three modes are “almost never found together outside his poems”. Works * * Poetry * Ommateum, with Doxology. Philadelphia: Dorrance, 1955. * Expressions of Sea Level. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1964. * Corsons Inlet. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1965. Reprinted by Norton, 1967. ISBN 0-393-04463-7 * Tape for the Turn of the Year. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1965. Reprinted by Norton, 1972. ISBN 0-393-00659-X * Northfield Poems. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1966. * Selected Poems. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1968. * Uplands. New York: Norton, 1970. ISBN 0-393-04322-3 * Briefings: Poems Small and Easy. New York: Norton, 1971. ISBN 0-393-04326-6 * Collected Poems, 1951-1971. New York: Norton, 1972. ISBN 0-393-04241-3—winner of the National Book Award * Sphere: The Form of a Motion. New York: Norton, 1974. ISBN 0-393-04388-6—winner of the Bollingen Prize for Poetry * Diversifications. New York: Norton, 1975. ISBN 0-393-04414-9 * The Selected Poems: 1951-1977. New York: Norton, 1977. ISBN 0-393-04465-3 * Highgate Road. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1977. * The Snow Poems . New York: Norton, 1977. ISBN 0-393-04467-X * Selected Longer Poems. New York: Norton, 1980. ISBN 0-393-01297-2 * A Coast of Trees. New York: Norton, 1981. ISBN 0-393-01447-9—winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award * Worldly Hopes. New York: Norton, 1982. ISBN 0-393-01518-1 * Lake Effect Country. New York: Norton, 1983. ISBN 0-393-01702-8 * The Selected Poems: Expanded Edition. New York: Norton, 1986. ISBN 0-393-02411-3 * Sumerian Vistas. New York: Norton, 1987. ISBN 0-393-02468-7 * The Really Short Poems. New York: Norton, 1991. ISBN 0-393-02870-4 * Garbage. New York: Norton, 1993. ISBN 0-393-03542-5—winner of the National Book Award * The North Carolina Poems. Alex Albright, ed. Rocky Mount, NC: NC Wesleyan College P, 1994. ISBN 0-933598-51-3 * Brink Road.New York: Norton, 1996. ISBN 0-393-03958-7 * Glare. New York: Norton, 1997. ISBN 0-393-04096-8 * Bosh and Flapdoodle: Poems. New York: Norton, 2005. ISBN 0-393-05952-9 * Selected Poems. David Lehman, ed. New York: Library of America, 2006. ISBN 1-931082-93-6 * The North Carolina Poems. New, expanded edition. Frankfort, KY: Broadstone Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9802117-2-6 * The Mule Poems. Fountain, NC: R. A. Fountain, 2010. ISBN 0-9842102-0-2 (chapbook) * Prose * Set in Motion: Essays, Interviews, and Dialogues (1996) * An Image for Longing: Selected Letters and Journals of A.R. Ammons, 1951-1974. Ed. Kevin McGuirk. Victoria, BC: ELS Editions, 2014. ISBN 978-1550584561 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._R._Ammons

David Ignatow (February 7, 1914– November 17, 1997) was an American poet. Life David Ignatow was born in Brooklyn on February 7, 1914, and spent most of his life in the New York City area. He died on November 17, 1997, at his home in East Hampton, New York. His papers are held at University of California, San Diego. Ignatow began his professional career as a businessman. After committing wholly to poetry, Ignatow worked as an editor of American Poetry Review, Analytic, Beloit Poetry Journal, and Chelsea Magazine, and as poetry editor of The Nation. He taught at the New School for Social Research, the University of Kentucky, the University of Kansas, Vassar College, York College, City University of New York, New York University, and Columbia University. He was president of the Poetry Society of America from 1980 to 1984 and poet-in-residence at the Walt Whitman Birthplace Association in 1987. Awards * Ignatow’s many honors include a Bollingen Prize, two Guggenheim fellowships, the John Steinbeck Award, and a National Institute of Arts and Letters award “for a lifetime of creative effort.” He received the Shelley Memorial Award (1966), the Frost Medal (1992), and the William Carlos Williams Award (1997) of the Poetry Society of America. Bibliography * Living Is What I Wanted: Last Poems (BOA Editions, 1999) * At My Ease: Uncollected Poems of the Fifties and Sixties (1998) * I Have a Name (1996) * The End Game and Other Stories (1996) * Against the Evidence: Selected Poems, 1934-1994 (1994) * Despite the Plainness of the Day: Love Poems (1991) * Shadowing the Ground (1991) * New and Collected Poems, 1970-1985 (1986) * Leaving the Door Open (1984) * Whisper the Earth (1981) * Conversations (1980) * Sunlight (1979) * Tread the Dark (1978) * Selected Poems (1975) * Facing the Tree (1975) * Poems: 1934-1969 (1970) * Rescue the Dead (1968) * Earth Hard: Selected Poems (1968) * Figures of the Human (1964) * Say Pardon (1962) * The Gentle Weightlifter (1955) * Poems (1948) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Ignatow