Info

Charles Stuart Calverley (/ˈkɑːvərlɪ/; 22 December 1831– 17 February 1884) was an English poet and wit. He was the literary father of what has been called “the university school of humour”. Early life He was born at Martley, Worcestershire, and given the name Charles Stuart Blayds. In 1852, his father, the Rev. Henry Blayds, resumed the old family name of Calverley, which his grandfather had exchanged for Blayds in 1807. Charles went up to Balliol College, Oxford from Harrow School in 1850, and was soon known in Oxford as the most daring and high-spirited undergraduate of his time. He was a universal favourite, a delightful companion, a brilliant scholar and the playful enemy of all “dons.” In 1851 he won the Chancellor’s prize for Latin verse, but it is said that the entire exercise was written in an afternoon, when his friends had locked him into his rooms, refusing to let him out until he had finished what they were confident would prove the prize poem. A year later, to avoid the consequences of a college escapade (he had been expelled from Oxford), he too changed his name to Calverley and moved to Christ’s College, Cambridge. Here he was again successful in Latin verse, the only undergraduate to have won the Chancellor’s prize at both universities. In 1856 he took second place in the first class in the Classical Tripos. Later life He was elected fellow of Christ’s (1858), published Verses and Translations in 1862, and was called to the bar in 1865. Injuries sustained in a skating accident prevented him from following a professional career, and during the last years of his life he was an invalid. He died of Bright’s disease. Works * Nowadays he is best-known (at least in Cambridge, his adoptive home) as the author of the Ode to Tobacco which is to be found on a bronze plaque in Rose crescent, on the wall of what used to be Bacon’s the tobacconist. * His Translations into English and Latin appeared in 1866; his Theocritus translated into English Verse in 1869; Fly Leaves in 1872; and Literary Remains in 1885. * His Complete Works, with a biographical notice by Walter Joseph Sendall, a contemporary at Christ’s and his brother-in-law, appeared in 1901. * George W. E. Russell said of him: * He was a true poet; he was one of the most graceful scholars that Cambridge ever produced; and all his exuberant fun was based on a broad and strong foundation of Greek, Latin, and English literature. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Stuart_Calverley

Christopher Smart (11 April 1722– 21 May 1771), also known as “Kit Smart”, “Kitty Smart”, and “Jack Smart”, was an English poet. He was a major contributor to two popular magazines and a friend to influential cultural icons like Samuel Johnson and Henry Fielding. Smart, a high church Anglican, was widely known throughout London.

Jean Ingelow (17 March 1820– 20 July 1897), was an English poet and novelist. She also wrote several stories for children. Early life Born at Boston, Lincolnshire, she was the daughter of William Ingelow, a banker. As a girl she contributed verses and tales to magazines under the pseudonym of Orris, but her first (anonymous) volume, A Rhyming Chronicle of Incidents and Feelings, which came from an established London publisher, did not appear until her thirtieth year. This was called charming by Tennyson, who declared he should like to know the author; they later became friends. Professional life Jean Ingelow followed this book of verse in 1851 with a story, Allerton and Dreux, but it was the publication of her Poems in 1863 which suddenly made her a popular writer. This ran rapidly through numerous editions and was set to music, proving very popular for English domestic entertainment. Her work often focused on religious introspection. In the United States, her poems obtained great public acclaim, and the collection was said to have sold 200,000 copies. In 1867 she edited, with Dora Greenwell, The Story of Doom and other Poems, a collection of poetry for children At that point Ingelow gave up verse for a while and became industrious as a novelist. Off the Skelligs appeared in 1872, Fated to be Free in 1873, Sarah de Berenger in 1880, and John Jerome in 1886. She also wrote Studies for Stories (1864), Stories told to a Child (1865), Mopsa the Fairy (1869), and other stories for children. Ingelow’s children’s stories were influenced by Lewis Carroll and George MacDonald. Mopsa the Fairy, about a boy who discovers a nest of fairies and discovers a fairyland while riding on the back of an albatross) was one of her most popular works (it was reprinted in 1927 with illustrations by Dorothy P. Lathrop). Anne Thaxter Eaton, writing in A Critical History of Children’s Literature, calls the book “a well-constructed tale”, with “charm and a kind of logical make-believe.” Her third series of Poems was published in 1885. Jean Ingelow’s last years were spent in Kensington, by which time she had outlived her popularity as a poet. She died in 1897 and was buried in Brompton Cemetery, London. Criticism Ingelow’s poems, collected in one volume in 1898, were frequently popular successes. “Sailing beyond Seas” and “When Sparrows build in Supper at the Mill” were among the most popular songs of the day. Her best-known poems include “The High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire” and “Divided”. Many, particularly her contemporaries, have defended her work. Gerald Massey described The High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire as “a poem full of power and tenderness” and Susan Coolidge remarked in a preface to an anthology of Ingelow’s poems, "She stood amid the morning dew/ And sang her earliest measure sweet/ Sang as the lark sings, speeding fair/ to touch and taste the purer air". “Sailing beyond Seas” (or “The Dove on the Mast”) was a favourite poem of Agatha Christie, who quotes it in two of her novels, The Moving Finger and Ordeal by Innocence. Still, the larger literary world largely dismissed her work. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, for example, wrote: "If we had nothing of Jean Ingelow’s but the most remarkable poem entitled Divided, it would be permissible to suppose the loss [of her], in fact or in might-have-been, of a poetess of almost the highest rank.... Jean Ingelow wrote some other good things, but nothing at all equalling this; while she also wrote too much and too long." Some of this criticism has overtones of dismissiveness of her as a female writer: “ Unless a man is an extraordinary coxcomb, a person of private means, or both, he seldom has the time and opportunity of committing, or the wish to commit, bad or indifferent verse for a long series of years; but it is otherwise with woman.” There have many parodies of her poetry, particularly of her archaisms, flowery language and perceived sentimentality. These include “Lovers, and a Reflexion” by Charles Stuart Calverley and “Supper at the Kind Brown Mill”, a parody of her “Supper at the Mill”, which appears in Gilbert Sorrentino’s satirical novel Blue Pastoral (1983). It is no longer fashionable to criticise poetry for the use of dialect.

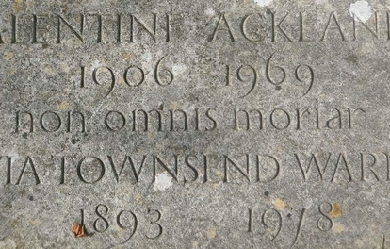

Elizabeth Daryush (8 December 1887 – 7 April 1977) was an English poet. Life Daryush was the daughter of Robert Bridges; her maternal grandfather was Alfred Waterhouse. She married Ali Akbar Daryush, whom she had met when he was studying at the University of Oxford, and thereafter spent some time in Persia; most of her life was spent in Boars Hill, outside Oxford, where the Elizabeth Daryush Memorial Garden is named for her. Writings Poetry Daryush, daughter of English poet laureate Robert Bridges (some of her early work was published as 'Elizabeth Bridges’), followed her father’s lead not only in choosing poetry as her life’s work but also in the traditional style of poetry she chose to write. The themes of her work are often critical of the upper classes and the social injustice their privilege levied upon others. This characteristic was not present in her early work, including her first two books of poems, published under the name Elizabeth Bridges, which appeared while she was still in her twenties. According to John Finlay, writing in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, Daryush’s “early poetry is preoccupied with rather conventional subject matter and owes a great deal to the Edwardians.” Syllabic style Daryush took her father’s experiment in syllabic verse a step farther by making it less experimental; whereas Bridges’ syllable count excluded elidable syllables, producing some variation in the total number of pronounced syllables per line, Daryush’s was strictly aural, counting all syllables actually sounded when the poem was read aloud. It is for her successful experiments with syllabic meter that Daryush is best known to contemporary readers, as exampled in her poem Accentedal in the quaternion form. Yvor Winters, the poet and critic, considered Daryush more successful in writing syllabics than was her father, noting that her poem Still-Life was her finest syllabic experiment, and also a companion-piece to Children of Wealth. Winters considered the social context of Still Life, which is nowhere mentioned, yet from which the poem draws its power. Characteristics Beyond its social content, Daryush’s work is also recognized for a consistent and well-defined personal vision. As Finlay noted, "For her. . .poetry always dealt with the `stubborn fact’ of life as it is, and the only consolations it offered were those of understanding and a kind of half-Christian, half-stoical acceptance of the inevitable." However, he also argued that Daryush’s best poems transcend such fatalism, “dealing with the moral resources found in one’s own being. . .and a recognition of the beauties in the immediate, ordinary world around us.” In many of her terse short poems, there is formal and intellectual mastery; her last, longest and most amibitious poem, ‘Air and Variations,’ was a formal tribute to Gerard Manly Hopkins Daryush has been described as a pioneer technical innovator, a poet of the highest dedication and seriousness whose poetry grapples with life’s intensest issues.

Horace Smith (born Horatio Smith) (31 December 1779 – 12 July 1849) was an English poet and novelist, perhaps best known for his participation in a sonnet-writing competition with Percy Bysshe Shelley. It was of him that Shelley said: “Is it not odd that the only truly generous person I ever knew who had money enough to be generous with should be a stockbroker? He writes poetry and pastoral dramas and yet knows how to make money, and does make it, and is still generous.” Smith was born in London, the son of a London solicitor, and the fifth of eight children. He was educated at Chigwell School with his elder brother James Smith, also a writer. Horace first came to public attention in 1812 when he and his brother James (four years older than he) produced a popular literary parody connected to the rebuilding of the Drury Lane Theatre, after a fire in which it had been burnt down. The managers offered a prize of £50 for an address to be recited at the Theatre's reopening in October. The Smith brothers hit on the idea of pretending that the most popular poets of the day had entered the competition and writing a book of addresses rejected from the competition in parody of their various styles. James wrote parodies of Wordsworth, Southey, Coleridge and Crabbe, and Horace took on Byron, Moore, Scott and Bowles. The book was a smash, and went through seven editions within three months. The Rejected Addresses still stands the most widely popular parodies ever published in the country. The book was written without malice; none of the poets caricatured took offence, while the imitation is so clever that both Byron and Scott claimed that they could scarcely believe they had not written the addresses ascribed to them. The only other collaboration by the two brothers was Horace in London (1813). Smith went on to become a prosperous stockbroker. Smith knew Shelley as a member of the circle around Leigh Hunt. Smith helped to manage Shelley's finances. Sonnet-writing competitions were not uncommon; Shelley and Keats wrote competing sonnets on the subject of the Nile River. Inspired by Diodorus Siculus (Book 1, Chapter 47), they each wrote and submitted a sonnet on the subject to The Examiner. Shelley's Ozymandias was published on 11 January 1818 under the pen name Glirastes, and Smith's On a Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below was published on 1 February 1818 with the initials H.S. (and later in his collection Amarynthus). After making his fortune, Horace Smith produced a series of historical novels: Brambletye House (1826), Tor Hill (1826), Reuben Apsley (1827), Zillah (1828), The New Forest (1829), Walter Colyton (1830), among others. Three volumes of Gaieties and Gravities, published by him in 1826, contain many clever essays both in verse and prose, but the only piece that remains much remembered is the “Address to the Mummy in Belzoni's Exhibition.” Horace Smith died at Tunbridge Wells on 12 July 1849. References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace_Smith_(poet)

Anne Killigrew (1660–1685) was an English poet. Born in London, Killigrew is perhaps best known as the subject of a famous elegy by the poet John Dryden entitled To The Pious Memory of the Accomplish’d Young Lady Mrs. Anne Killigrew (1686). She was however a skilful poet in her own right, and her Poems were published posthumously in 1686. Dryden compared her poetic abilities to the famous Greek poet of antiquity, Sappho. Killigrew died of smallpox aged 25. Early life and inspiration Anne Killigrew was born in early 1660, before the Restoration, at St. Martin’s Lane in London. Not much is known about her mother Judith Killigrew, but her father Dr. Henry Killigrew published several sermons and poems as well as a play called The Conspiracy. Her two paternal uncles were also published playwrights. Sir William Killigrew (1606–1695) published two collections of plays and Thomas Killigrew (1612–1683) not only wrote plays but built the theatre now known as Drury Lane. Her father and her uncles had close connections with the Stuart Court, serving Charles I, Charles II, and his Queen, Catherine of Braganza. Anne was made a personal attendant, before her death, to Mary of Modena, Duchess of York. Little is recorded about Anne’s education, but it is known that she kept up with her social class, and she received instruction in both poetry and painting in which she excelled. Her theatrical background added to her use of shifting voices in her poetry. In John Dryden’s Ode to Anne he points out that “Art she had none, yet wanted none. For Nature did that want supply” (Stanza V). Killigrew most likely got her education through studying the Bible, Greek mythology, and philosophy. Mythology was often expressed throughout her paintings and poetry. Inspiration for Killigrew’s poetry came from her knowledge of Greek myths and Biblical proverbs as well as from some very influential female poets who lived during the Restoration period: Katherine Philips and Anne Finch (also a maid to Mary of Modena at the same time as Killigrew). Mary of Modena encouraged the French tradition of precieuses (patrician women intellectuals) which pressed women’s participation in theatre, literature, and music. In effect, Killigrew was surrounded with a poetic feminist inspiration on a daily basis in Court: she was encompassed by strong intelligent women who encouraged her writing career as much as their own. With this motivation came a short book of only thirty-three poems published soon after her death by her father. It was not abnormal for poets, especially for women, never to see their work published in their lifetime. Since Killigrew died at the young age of 25 she was only able to produce a small collection of poetry. In fact, the last three poems were only found among her papers and it is still being debated about whether or not they were actually written by her. Inside the book is also a self painted portrait of Anne and the Ode by family friend and poet John Dryden. The Poet and the Painter Anne Killigrew excelled in multiple media, which was noted by contemporary poet, mentor, and family friend, John Dryden in his dedicatory ode to Killigrew. He addresses her as "the Accomplisht Young LADY Mrs Anne Killigrew, Excellent in the two Sister-Arts of Poësie, and Painting." Scholars believe that Kelligrew painted a total of 15 paintings; however, only four are known to exist today. Many of her paintings display biblical and mythological imagery. Yet, Killigrew was also skilled at portraits, and her works include a self-portrait and a portrait of James, Duke of York. Some of her poetry references her own paintings, such as her poem “On a Picture Painted by her self, representing two Nimphs of DIANA’s, one in a posture to Hunt, the other Batheing.” Both her poems and her paintings place emphasis on women and nature, suggesting female rebellion in a male-dominated society. Contemporary critics noted her exceptional skill in both mediums, with John Dryden addressing his dedicatory John Dryden and critical reception Killigrew is best known for being the subject of John Dryden’s famous, extolling ode, which praises Killigrew for her beauty, virtue, and literary talent. However, Dryden was one of several contemporary admirers of Killigrew, and the posthumous collection of her work published in 1686 included several additional poems commending her literary merit, irreproachable piety, and personal charm. Nonetheless, critics often disagree about the nature of Dryden’s ode: some believe his praise to be too excessive, and even ironic. These individuals condemn Killigrew for using well worn and conventional topics, such as death, love, and the human condition, in her poetry and pastoral dialogues. In fact, Alexander Pope, a prominent critic, as well as the leading poet of the time, labelled her work “crude” and “unsophisticated.” As a young poet who had only distributed her work via manuscript prior to her death, it is possible that Killigrew was not ready to see her work published so soon. Some say Dryden defended all poets because he believed them to be teachers of moral truths; thus, he felt Killigrew, as an inexperienced yet dedicated poet, deserved his praise. However, Anthony Wood in his 1721 essay defends Dryden’s praise, confirming that Killigrew “was equal to, if not superior” to any of the compliments lavished upon her. Furthermore, Wood asserts that Killigrew must have been well received in her time, otherwise “her Father would never have suffered them to pass the Press” after her death. Authorship controversy Then, there is the question of the last three poems that were found among her papers. They seem to be in her handwriting, which is why Killigrew’s father added them to her book. The poems are about the despair the author has for another woman, and could possibly be autobiographical if they are in fact by Killigrew. Some of her other poems are about failed friendships, possibly with Anne Finch, so this assumption may have some validity. An early death Killigrew died of smallpox on 16 June 1685, when she was only 25 years old. She is buried in the Chancel of the Savoy Chapel (dedicated to St John the Baptist) where a monument was built in her honour, but has since been destroyed by a fire.

John Skelton, also known as John Shelton (c. 1463– 21 June 1529), possibly born in Diss, Norfolk, was an English poet. He had been a tutor to King Henry VIII of England and died at Westminster. Education Skelton is said to have been educated at Oxford. He certainly studied at Cambridge, and he is probably the “one Scheklton” mentioned by William Cole as taking his M.A. degree in 1484. In 1490, William Caxton in the preface to The Boke of Eneydos compyled by Vyrgyle refers to him in terms which prove that Skelton had already won a reputation as a scholar. “But I pray mayster John Skelton,” he says, “late created poete laureate in the unyversite of Oxenforde, to oversee and correct this sayd booke... for him I know for suffycyent to expowne and englysshe every dyffyculte that is therin. For he hath late translated the epystlys of Tulle, and the boke of dyodorus siculus, and diverse other works... in polysshed and ornate termes craftely... suppose he hath drunken of Elycons well.” The laureateship referred to was a degree in rhetoric. In 1493 Skelton received the same honour at Cambridge, and also, it is said, at Leuven. He found a patron in the pious and learned Countess of Richmond, Henry VII’s mother, for whom he wrote Of Mannes Lyfe the Peregrynacioun, a translation, now lost, of Guillaume de Diguileville’s Pèlerinage de la vie humaine. An elegy “Of the death of the noble prince Kynge Edwarde the forth,” included in some of the editions of the Mirror for Magistrates, and another (1489) on the death of Henry Percy, fourth earl of Northumberland, are among his earliest poems. Poet laureate In the last decade of the century he was appointed tutor to Prince Henry (afterwards King Henry VIII). He wrote for his pupil a lost Speculum principis, and Erasmus, in dedicating an ode to the prince in 1500, speaks of Skelton as “unum Britannicarum literarum lumen ac decus.” In 1498 he was successively ordained sub-deacon, deacon and priest. He seems to have been imprisoned in 1502, but no reason is known for his disgrace. (It has been said that he offended Wolsey but this would be impossible if the date is correct, given Wolsey was not yet an influential figure at court - Wolsey’s rise began in 1508). Two years later he retired from regular attendance at court to become rector of Diss, a benefice which he retained nominally until his death. Skelton frequently signed himself “regius orator” and poet-laureate, but there is no record of any emoluments paid in connection with these dignities, although the Abbé du Resnel, author of Recherches sur les poètes couronnez, asserts that he had seen a patent (1513–1514) in which Skelton was appointed poet-laureate to Henry VIII. As rector of Diss he caused great scandal among his parishioners, who thought him, says Anthony Wood, more fit for the stage than for the pew or the pulpit. He was secretly married to a woman who lived in his house, and he had earned the hatred of the Dominican monks by his fierce satire. Consequently, he came under the formal censure of Richard Nix, the bishop of the diocese, and appears to have been temporarily suspended. After his death a collection of farcical tales, no doubt chiefly, if not entirely, apocryphal, gathered round his name—The Merie Tales of Skelton. During the rest of the century he figured in the popular imagination as an incorrigible practical joker. His sarcastic wit made him some enemies, among them Sir Christopher Garnesche or Garneys, Alexander Barclay, William Lilly and the French scholar, Robert Gaguin (c. 1425-1502). With Garneys he engaged in a regular “flyting,” undertaken, he says, at the king’s command, but Skelton’s four poems read as if the abuse in them were dictated by genuine anger. Earlier in his career he had found a friend and patron in Cardinal Wolsey, and the dedication to the cardinal of his Replycacion is couched in the most flattering terms. But in 1522, when Wolsey in his capacity of legate dissolved convocation at St Paul’s, Skelton put in circulation the couplet: Gentle Paul, laie doune thy sweard For Peter of Westminster hath shaven thy beard. In Colyn Cloute he incidentally attacked Wolsey in a general satire on the clergy, “Speke, Parrot” and “Why come ye nat to Courte?” are direct and fierce invectives against the cardinal who is said to have more than once imprisoned the author. To avoid another arrest Skelton took sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. He was kindly received by the abbot, John Islip, who continued to protect him until his death. The inscription on his tomb in the neighbouring church of St Margaret’s described him as vales pierius. It is thought that Skelton wrote “Why come ye nat to Courte?” having been inspired by Sir Thomas Spring, a merchant in Suffolk who had fallen out with Wolsey over tax. His works In his Garlande of Laurell Skelton gives a long list of his works, only a few of which are extant. The garland in question was worked for him in silks, gold and pearls by the ladies of the Countess of Surrey at Sheriff Hutton Castle, where he was the guest of the duke of Norfolk. The composition includes complimentary verses to the various ladies concerned, and a good deal of information about himself. But it is as a satirist that Skelton merits attention. The Bowge of Court is directed against the vices and dangers of court life. He had already in his Boke of the Thre Foles drawn on Alexander Barclay’s version of the Narrenschijf of Sebastian Brant, and this more elaborate and imaginative poem belongs to the same class. Skelton, falling into a dream at Harwich, sees a stately ship in the harbour called the Bowge of Court, the owner of which is the “Dame Saunce Pere”. Her merchandise is Favour; the helmsman Fortune; and the poet, who figures as Drede (modesty), finds on board F’avell (the flatterer), Suspect, Harvy Hafter (the clever thief), Dysdayne, Ryotte, Dyssymuler and Subtylte, who all explain themselves in turn, until at last Drede, who finds they are secretly his enemies, is about to save his life by jumping overboard, when he wakes with a start. Both of these poems are written in the seven-lined Rhyme Royal, a Continental verse-form first used in English by Chaucer, but it is in an irregular metre of his own—known as “Skeltonics”—that his most characteristic work was accomplished. The Boke of Phyllyp Sparowe, the lament of Jane Scroop, a schoolgirl in the Benedictine convent of Carrow near Norwich, for her dead bird, was no doubt inspired by Catullus. It is a poem of some 1,400 lines and takes many liberties with the formularies of the church. The digressions are considerable. We learn what a wide reading Jane had in the romances of Charlemagne, of the Round Table, The Four Sons of Aymon and the Trojan cycle. Skelton finds space to give an opinion of Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower and John Lydgate. Whether we can equate this opinion, voiced by the character of Jane, with Skelton’s own is contentious. It would appear that he seems fully to have realised Chaucer’s value as a master of the English language. Gower’s matter was, Jane tells us, “worth gold,” but his English she regards as antiquated. The verse in which the poem is written, called from its inventor “Skeltonical,” is here turned entirely to whimsical use. The lines are usually six-syllabled, but vary in length, and rhyme in groups of two, three, four and even more. It is not far removed from the old alliterative English verse, and well fitted to be chanted by the minstrels who had sung the old ballads. For its comic admixture of Latin Skelton had abundant example in French and Low Latin macaronic verse. He makes frequent use of Latin and French words to carry out his exacting system of frequently recurring rhymes. This breathless, voluble measure was in Skelton’s energetic hands an admirable vehicle for invective, but it easily degenerated into doggerel. By the end of the 16th century he was a “rude rayling rimer” (Puttenham, Arte of English Poesie), and at the hands of Pope and Warton he fared even worse. His own criticism is a just one: For though my ryme be ragged, Tattered and jagged, Rudely rayne beaten, Rusty and moughte eaten, It hath in it some pyth. Colyn Cloute represents the average country man who gives his opinions on the state of the church. There is no more scathing indictment of the sins of the clergy before the Reformation. He exposes their greed, their ignorance, the ostentation of the bishops and the common practice of simony, but takes care to explain that his accusations do not include all and that he writes in defence of, not against, the church. He repeatedly hits at Wolsey even in this general satire, but not directly. Speke, Parrot has only been preserved in a fragmentary form, and is exceedingly obscure. It was apparently composed at different times, but in the latter part of the composition he openly attacks Wolsey. In Why come ye not to Courte? there is no attempt at disguise. The wonder is not that the author had to seek sanctuary, but that he had any opportunity of doing so. He rails at Wolsey’s ostentation, at his almost royal authority, his overbearing manner to suitors high and low, and taunts him with his mean extraction. This scathing invective was not allowed to be printed in the cardinal’s lifetime, but it was no doubt widely circulated in manuscript and by repetition. The charge of coarseness regularly brought against Skelton is based chiefly on The Tunnynge of Elynoare Rummynge, a realistic description in the same metre of the drunken women who gathered at a well-known ale-house kept by Elynour Rummynge at Leatherhead, not far from the royal palace of Nonsuch. “Skelton Laureate against the Scottes” is a fierce song of triumph celebrating the victory of Flodden. “Jemmy is ded And closed in led, That was theyr owne Kynge,” says the poem; but there was an earlier version written before the news of James IV’s death had reached London. This, which is the earliest singly printed ballad in the language, was entitled A Ballade of the Scottysshe Kynge, and was rescued in 1878 from the wooden covers of a copy of Huon de Bordeaux. “Howe the douty Duke of Albany, lyke a cowarde knight” deals with the campaign of 1523, and contains a panegyric of Henry VIII. To this is attached an envoi to Wolsey, but it must surely have been misplaced, for both the satires on the cardinal are of earlier date. Skelton also wrote three plays, only one of which survives. Magnificence is one of the best examples of the morality play. It deals with the same topic as his satires, the evils of ambition; the play’s moral, namely “how suddenly worldly wealth doth decay” was a favourite one with him. Thomas Warton in his History of English Poetry described another piece titled Nigramansir, printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1504. It deals with simony and the love of money in the church; but no copy is known to exist, and some suspicion has been cast on Warton’s statement. Illustration of the hold Skelton had on the public imagination is supplied from the stage. A play (1600) called Scogan and Shelton, by Richard Hathwaye and William Rankins, is mentioned by Henslowe. In Anthony Munday’s Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntingdon, Skelton acts the part of Friar Tuck, and Ben Jonson in his masque, The Fortunate Isles, introduced Skogan and Skelton in like habits as they lived. Very few of Skelton’s productions are dated, and their titles are here necessarily abbreviated. De Worde printed the Bowge of Court twice. Divers Batettys and dyties salacious devysed by Master Shelton Laureat, and Shelton Laureate agaynste a comely Coystroune have no date or printer’s name, but are evidently from the press of Richard Pynson, who also printed Replycacion against certain yang scalers, dedicated to Wolsey. The Garlande or Chapelet of Laurell was printed by Richard Faukes (1523); Magnificence, A goodly interlude, probably by John Rastell about 1533, reprinted (1821) for the Roxburghe Club. Hereafter foloweth the Boke of Phyllyp Sparowe was printed by Richard Kele (1550?), Robert Toy, Antony Kitson (1560?), Abraham Veale (1570?), John Walley, John Wyght (1560?). Hereafter foloweth certaine bokes compyled by mayster Shelton... including “Speke, Parrot,” “Ware the Hawke,” “Elynoure Rumpiynge” and others, was printed by Richard Lant (1550?), John King and Thomas March (1565?), by John Day (1560). Hereafter foloweth a title boke called Colyn Cloute and Hereafter... why come ye nat to Courte? were printed by Richard Kele (1550?) and in numerous subsequent editions. Pithy, plesaunt and profitable workes of maister Shelton, Poete Laureate. Nowe collected and newly published was printed in 1568, and reprinted in 1736. A scarce reprint of Filnour Rummin by Samuel Rand appeared in 1624. Five of Skelton’s 'Tudor Portraits’, including 'The Tunnying of Elynour Rummyng’ were set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams in or around 1935. Although he changed the text here and there to suit his music, the sentiments are well expressed. The other four poems are 'My pretty Bess’,'Epitaph of John Jayberd of Diss’, 'Jane Scroop (her lament for Philip Sparrow)', and 'Jolly Rutterkin’. The music is rarely performed, although it is immensely funny, and captures the coarseness of Skelton in an inspired way. See The Poetical Works of John Shelton; with Notes and some account of the author and his writings, by the Rev. Alexander Dyce (2 vols., 1843). A selection of his works was edited by WH Williams (London, 1902). See also Zur Charakteristik John Skeltons by Dr Arthur Koelbing (Stuttgart, 1904); F Brie, “Skelton Studien” in Englische Studien, vol. 38 (Heilbronn, 1877, etc.); A Rey, Skelton’s Satirical Poems... (Berne, 1899); A Thummel, Studien über John Skelton (Leipzig-Reudnitz, 1905); G Saintsbury, Hist. of Eng. Prosody (vol. i, 1906); and A Kolbing in the Cambridge History of English Literature (vol. iii, 1909). Family John Skelton’s lineage is difficult to prove. He was probably related to Sir John Shelton and his children, who also came from Norfolk. Sir John’s daughter, Mary Shelton, was a mistress of Henry VIII’s during the reign of her cousin, Anne Boleyn. Mary Shelton was the main editor and contributor to the Devonshire MS, a collection of poems written by various members of the court. Interestingly, it is said that several of Skelton’s works were inspired by women who were to become mothers to two of Henry VIII’s six wives. Elizabeth Boleyn, Countess of Wiltshire and Ormonde, was said to be so beautiful that Skelton compared her to Cressida and a popular but unverifiable legend also suggests that several poems were inspired by Margery Wentworth. Elizabeth was the mother of Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife; Margery was the mother of his third, Jane Seymour. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Skelton

John Fletcher (1579–1625) was a Jacobean playwright. Following William Shakespeare as house playwright for the King’s Men, he was among the most prolific and influential dramatists of his day; both during his lifetime and in the early Restoration, his fame rivaled Shakespeare’s. Though his reputation has been far eclipsed since, Fletcher remains an important transitional figure between the Elizabethan popular tradition and the popular drama of the Restoration. Biography Early life Fletcher was born in December 1579 (baptised 20 December) in Rye, Sussex, and died of the plague in August 1625 (buried 29 August in St. Saviour’s, Southwark). His father Richard Fletcher was an ambitious and successful cleric who was in turn Dean of Peterborough, Bishop of Bristol, Bishop of Worcester, and Bishop of London (shortly before his death) as well as chaplain to Queen Elizabeth. As dean of Peterborough, Richard Fletcher, at the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, at Fotheringay “knelt down on the scaffold steps and started to pray out loud and at length, in a prolonged and rhetorical style as though determined to force his way into the pages of history”. He cried out at her death, “So perish all the Queen’s enemies!” Richard Fletcher died shortly after falling out of favour with the queen, over a marriage the queen had advised against. He appears to have been partly rehabilitated before his death in 1596; however, he died substantially in debt. The upbringing of John Fletcher and his seven siblings was entrusted to his paternal uncle Giles Fletcher, a poet and minor official. His uncle’s connections ceased to be a benefit, and may even have become a liability, after the rebellion of the Earl of Essex, who had been his patron. Fletcher appears to have entered Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University in 1591, at the age of eleven. It is not certain that he took a degree, but evidence suggests that he was preparing for a career in the church. Little is known about his time at college, but he evidently followed the same path previously trodden by the University wits before him, from Cambridge to the burgeoning commercial theatre of London. Collaborations with Beaumont In 1606, he began to appear as a playwright for the Children of the Queen’s Revels, then performing at the Blackfriars Theatre. Commendatory verses by Richard Brome in the Beaumont and Fletcher 1647 folio place Fletcher in the company of Ben Jonson; a comment of Jonson’s to Drummond corroborates this claim, although it is not known when this friendship began. At the beginning of his career, his most important association was with Francis Beaumont. The two wrote together for close to a decade, first for the children and then for the King’s Men. According to an anecdote transmitted or invented by John Aubrey, they also lived together (in Bankside), sharing clothes and having “one wench in the house between them.” This domestic arrangement, if it existed, was ended by Beaumont’s marriage in 1613, and their dramatic partnership ended after Beaumont fell ill, probably of a stroke, the same year. Successor to Shakespeare By this time, Fletcher had moved into a closer association with the King’s Men. He collaborated with Shakespeare on Henry VIII, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and the lost Cardenio, which is probably (according to some modern scholars) the basis for Lewis Theobald’s play Double Falsehood. A play he wrote singly around this time, The Woman’s Prize or the Tamer Tamed, is a sequel to The Taming of the Shrew. In 1616, after Shakespeare’s death, Fletcher appears to have entered into an exclusive arrangement with the King’s Men similar to Shakespeare’s. Fletcher wrote only for that company between the death of Shakespeare and his own death nine years later. He never lost his habit of collaboration, working with Nathan Field and later with Philip Massinger, who succeeded him as house playwright for the King’s Men. His popularity continued unabated throughout his life; during the winter of 1621, three of his plays were performed at court. He died in 1625, apparently of the plague. He seems to have been buried in what is now Southwark Cathedral, although the precise location is not known; there is a reference by Aston Cockayne to a single grave for Fletcher and Massinger (also buried in Southwark). What is more certain is that two simple adjacent stones in the floor of The Choir of Southwark Cathedral, one marked 'Edmond Shakespeare 1607' the other 'John Fletcher 1625' refer to Shakespeare’s younger brother and the playwright. His mastery is most notable in two dramatic types, tragicomedy and comedy of manners. Stage history Fletcher’s early career was marked by one significant failure, of The Faithful Shepherdess, his adaptation of Giovanni Battista Guarini’s Il Pastor Fido, which was performed by the Blackfriars Children in 1608. In the preface to the printed edition of his play, Fletcher explained the failure as due to his audience’s faulty expectations. They expected a pastoral tragicomedy to feature dances, comedy, and murder, with the shepherds presented in conventional stereotypes– as Fletcher put it, wearing “gray cloaks, with curtailed dogs in strings.” Fletcher’s preface in defence of his play is best known for its pithy definition of tragicomedy: "A tragicomedy is not so called in respect of mirth and killing, but in respect it wants [i.e., lacks] deaths, which is enough to make it no tragedy; yet brings some near it, which is enough to make it no comedy." A comedy, he went on to say, must be “a representation of familiar people,” and the preface is critical of drama that features characters whose action violates nature. In that case, Fletcher appears to have been developing a new style faster than audiences could comprehend. By 1609, however, he had found his stride. With Beaumont, he wrote Philaster, which became a hit for the King’s Men and began a profitable connection between Fletcher and that company. Philaster appears also to have initiated a vogue for tragicomedy; Fletcher’s influence has been credited with inspiring some features of Shakespeare’s late romances (Kirsch, 288-90), and his influence on the tragicomic work of other playwrights is even more marked. By the middle of the 1610s, Fletcher’s plays had achieved a popularity that rivalled Shakespeare’s and cemented the preeminence of the King’s Men in Jacobean London. After Beaumont’s retirement and early death in 1616, Fletcher continued working, both singly and in collaboration, until his death in 1625. By that time, he had produced, or had been credited with, close to fifty plays. This body of work remained a major part of the King’s Men’s repertory until the closing of the theatres in 1642. During the Commonwealth, many of the playwright’s best-known scenes were kept alive as drolls, the brief performances devised to satisfy the taste for plays while the theatres were suppressed. At the re-opening of the theatres in 1660, the plays in the Fletcher canon, in original form or revised, were by far the most common fare on the English stage. The most frequently revived plays suggest the developing taste for comedies of manners. Among the tragedies, The Maid’s Tragedy and, especially, Rollo Duke of Normandy held the stage. Four tragicomedies (A King and No King, The Humorous Lieutenant, Philaster, and The Island Princess) were popular, perhaps in part for their similarity to and foreshadowing of heroic drama. Four comedies (Rule a Wife And Have a Wife, The Chances, Beggars’ Bush, and especially The Scornful Lady) were also popular. Yet the popularity of these plays relative to those of Shakespeare and to new productions steadily eroded. By around 1710, Shakespeare’s plays were more frequently performed, and the rest of the century saw a steady erosion in performance of Fletcher’s plays. By 1784, Thomas Davies asserted that only Rule a Wife and The Chances were still current on stage. A generation later, Alexander Dyce mentioned only The Chances. Since then Fletcher has increasingly become a subject only for occasional revivals and for specialists. Fletcher and his collaborators have been the subject of important bibliographic and critical studies, but the plays have been revived only infrequently. Plays Because Fletcher collaborated regularly and widely, attempts to separate out Fletcher’s work from this collaborative fabric of plays have experienced difficulties in attribution. Fletcher collaborated most often with Beaumont and Massinger but also with Nathan Field, Shakespeare and others. Some of his early collaborations with Beaumont were later revised by Massinger, adding another layer of complexity to the collaborative texture of the plays. According to scholars such as Hoy, Fletcher used distinctive mannerisms that Hoy argued identify his presence. According to Hoy’s figures, he frequently uses ye instead of you, at rates sometimes approaching 50%. He employs 'em for them, along with a set of other preferences in contractions. He adds a sixth stressed syllable to a standard pentameter verse line—most often sir but also too or still or next. Various other specific habits and preferences may reveal his hand. The detection of this pattern, this personal Fletcherian textual profile, has persuaded some researchers that they have penetrated the Fletcher canon with what they consider success—and has in turn encouraged the use of similar techniques more broadly in the study of literature. [See: stylometry.] Some scholars, such as Jeffrey Masten and Gordon McMullan, have pointed out limitations of logic and method in Hoy’s and others’ attempts to distinguish playwrights on the basis of style and linguistic preferences. Bibliography has attempted to establish the writers of each play. Attempts to determine the exact “shares” of each writer (for instance by Cyrus Hoy) in particular plays is ongoing, based on patterns of textual and linguistic preferences, stylistic grounds, and idiosyncrasies of spelling. The list that follows gives a tentative verdict on the writing of the plays in Fletcher’s canon, with likeliest composition dates, dates of first publication, and dates of licensing by the Master of the Revels, where available. Solo plays The Faithful Shepherdess, pastoral (written 1608–9; printed 1609?) Valentinian, tragedy (1610–14; 1647) Monsieur Thomas, comedy (c. 1610–16; 1639) The Woman’s Prize, or The Tamer Tamed, comedy (c. 1611?; 1647) Bonduca, tragedy (1611–14; 1647) The Chances, comedy (c. 1613–25; 1647) Wit Without Money, comedy (c. 1614; 1639) The Mad Lover, tragicomedy (acted 5 January 1617; 1647) The Loyal Subject, tragicomedy (licensed 16 November 1618; revised 1633?; 1647) The Humorous Lieutenant, tragicomedy (c. 1619; 1647) Women Pleased, tragicomedy (c. 1619–23; 1647) The Island Princess, tragicomedy (c. 1620; 1647) The Wild Goose Chase, comedy (c. 1621; 1652) The Pilgrim, comedy (c. 1621; 1647) A Wife for a Month, tragicomedy (licensed 27 May 1624; 1647) Rule a Wife and Have a Wife, comedy (licensed 19 October 1624; 1640) Collaborations With Francis Beaumont: The Woman Hater, comedy (1606; 1607) Cupid’s Revenge, tragedy (c. 1607–12; 1615) Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding, tragicomedy (c. 1609; 1620) The Maid’s Tragedy, Tragedy (c. 1609; 1619) A King and No King, tragicomedy (1611; 1619) The Captain, comedy (c. 1609–12; 1647) The Scornful Lady, comedy (c. 1613; 1616) Love’s Pilgrimage, tragicomedy (c. 1615–16; 1647) The Noble Gentleman, comedy (c. 1613?; licensed 3 February 1626; 1647) With Beaumont and Massinger: Thierry and Theodoret, tragedy (c. 1607?; 1621) The Coxcomb, comedy (c. 1608–10; 1647) Beggars’ Bush, comedy (c. 1612–13? revised 1622?; 1647) Love’s Cure, comedy (c. 1612–13?; revised 1625?; 1647) With Massinger: Sir John van Olden Barnavelt, tragedy (August 1619; MS) The Little French Lawyer, comedy (c. 1619–23; 1647) A Very Woman, tragicomedy (c. 1619–22; licensed 6 June 1634; 1655) The Custom of the Country, comedy (c. 1619–23; 1647) The Double Marriage, tragedy (c. 1619–23; 1647) The False One, history (c. 1619–23; 1647) The Prophetess, tragicomedy (licensed 14 May 1622; 1647) The Sea Voyage, comedy (licensed 22 June 1622; 1647) The Spanish Curate, comedy (licensed 24 October 1622; 1647) The Lovers’ Progress or The Wandering Lovers, tragicomedy (licensed 6 December 1623; revised 1634; 1647) The Elder Brother, comedy (c. 1625; 1637) With Massinger and Field: The Honest Man’s Fortune, tragicomedy (1613; 1647) The Queen of Corinth, tragicomedy (c. 1616–18; 1647) The Knight of Malta, tragicomedy (c. 1619; 1647) With Shakespeare: Henry VIII, history (c. 1613; 1623) The Two Noble Kinsmen, tragicomedy (c. 1613; 1634) Cardenio, tragicomedy? (c. 1613) With Middleton and Rowley: Wit at Several Weapons, comedy (c. 1610–20; 1647) With Rowley: The Maid in the Mill (licensed 29 August 1623; 1647). With Field: Four Plays, or Moral Representations, in One, morality (c. 1608–13; 1647) With Massinger, Jonson, and Chapman: Rollo Duke of Normandy, or The Bloody Brother, tragedy (c. 1617; revised 1627–30?; 1639) With Shirley: The Night Walker, or The Little Thief, comedy (c. 1611; 1640) Uncertain: The Nice Valour, or The Passionate Madman, comedy (c. 1615–25; 1647) The Laws of Candy, tragicomedy (c. 1619–23; 1647) The Fair Maid of the Inn, comedy (licensed 22 January 1626; 1647) The Faithful Friends, tragicomedy (registered 29 June 1660; MS.) The Nice Valour may be a play by Fletcher revised by Thomas Middleton; The Fair Maid of the Inn is perhaps a play by Massinger, John Ford, and John Webster, either with or without Fletcher’s involvement. The Laws of Candy has been variously attributed to Fletcher and to John Ford. The Night-Walker was a Fletcher original, with additions by Shirley for a 1639 production. And some of the attributions given above are disputed by some scholars, as noted in connection with Four Plays in One. Rollo Duke of Normandy, an especially difficult case and a focus of much disagreement among scholars, may have been written around 1617, and later revised by Massinger. The first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647 collected 35 plays, most not published previously. The second folio of 1679 added 18 more, for a total of 53. The first folio included The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray’s Inn (1613), and the second The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1607), widely considered Beaumont’s solo works, although the latter was in early editions attributed to both writers. One play in the canon, Sir John Van Olden Barnavelt, existed in manuscript and was not published till 1883. In 1640 James Shirley’s The Coronation was misattributed to Fletcher upon its initial publication, and was included in the second Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1679. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Fletcher_(playwright)

Nicholas Breton (also Britton or Brittaine) (1545–1626), English poet and novelist, belonged to an old family settled at Layer Breton, Essex. Life His father, William Breton, a London merchant who had made a considerable fortune, died in 1559, and the widow (née Elizabeth Bacon) married the poet George Gascoigne before her sons had attained their majority. Nicholas Breton was probably born at the “capitall mansion house” in Red Cross Street, in the parish of St Giles without Cripplegate, mentioned in his father’s will. There is no official record of his residence at the university, but the diary of the Rev. Richard Madox tells us that he was at Antwerp in 1583 and was “once of Oriel College.” He married Ann Sutton in 1593, and had a family. He is supposed to have died shortly after the publication of his last work, Fantastickes (1626). Breton found a patron in Mary, countess of Pembroke, and wrote much in her honour until 1601, when she seems to have withdrawn her favour. It is probably safe to supplement the meagre record of his life by accepting as autobiographical some of the letters signed N.B. in A Poste with a Packet of Mad Letters (1603, enlarged 1637); the 19th letter of the second part contains a general complaint of many griefs, and proceeds as follows: “Hath another been wounded in the warres, fared hard, lain in a cold bed many a bitter storme, and beene at many a hard banquet? all these have I; another imprisoned? so have I; another long been sicke? so have I; another plagued with an unquiet life? so have I; another indebted to his hearts griefe, and fame would pay and cannot? so am I.” Works * Breton was a prolific author of considerable versatility and gift, popular with his contemporaries, and forgotten by the next generation. His work consists of religious and pastoral poems, satires, and a number of miscellaneous prose tracts. His religious poems are sometimes wearisome by their excess of fluency and sweetness, but they are evidently the expression of a devout and earnest mind. His lyrics are pure and fresh, and his romances, though full of conceits, are pleasant reading, remarkably free from grossness. His praise of the Virgin and his references to Mary Magdalene have suggested that he was a Roman Catholic, but his prose writings abundantly prove that he was an ardent Anglican. * Breton had little gift for satire, and his best work is to be found in his pastoral poetry. His Passionate Shepheard (1604) is full of sunshine and fresh air, and of unaffected gaiety. The third pastoral in this book—"Who can live in heart so glad As the merrie country lad"—is well known; with some other of Breton’s daintiest poems, among them the lullaby, “Come little babe, come silly soule,” (This poem, however, comes from The Arbor of Amorous Devises, which is only in part Breton’s work.)—it is incorporated in A. H. Bullen’s Lyrics from Elizabethan Romances (1890). His keen observation of country life appears also in his prose idyll, Wits Trenckrnour, “a conference betwixt a scholler and an angler,” and in his Fantastickes, a series of short prose pictures of the months, the Christian festivals and the hours, which throw much light on the customs of the times. Most of Breton’s books are very rare and have great bibliographical value. His works, with the exception of some belonging to private owners, were collected by Dr AB Grosart in the Chertsey Worthies Library in 1879, with an elaborate introduction quoting the documents for the poet’s history. * Breton’s poetical works, the titles of which are here somewhat abbreviated, include: * The Workes of a Young Wit (1577) * A Floorish upon Fancie (1577) * The Pilgrimage to Paradise (1592), with a prefatory letter by John Case * The Countess of Penbrook’s Passion (manuscript), first printed by JO Halliwell-Phillipps in 1853 [1] * Pasquil’s Fooles cappe (entered at Stationers’ Hall in 1600) * Pasquil’s Mistresse (1600) * Pasquil’s Passe and Passeth Not (1600) * Melancholike Humours (1600) - reprinted by Scholartis Press London. 1929. * Marie Magdalen’s Love: a Solemne Passion of the Soules Love (1595), the first part of which, a prose treatise, is probably by another hand; the second part, a poem in six-lined stanza, is certainly by Breton * A Divine Poem, including “The Ravisht Soul” and “The Blessed Weeper” (1601) * An Excellent Poem, upon the Longing of a Blessed heart (1601) * The Soules Heavenly Exercise (1601) * The Soules Harmony (1602) * Olde Madcappe newe Gaily mawfrey (1602) * The Mother’s Blessing (1602) * A True Description of Unthankfulnesse (1602) * The Passionate Shepheard (1604) * The Souies Immortail Crowne (1605) * The Honour of Valour (1605) * An Invective against Treason; I would and I would not (1614) * Bryton’s Bowre of Delights (1591), edited by Dr Grosart in 1893, an unauthorized publication which contained some poems disclaimed by Breton * The Arbor of Amorous Devises (entered at Stationers’ Hall, 1594), only in part Breton’s * contributions to England’s Helicon and other miscellanies of verse. * Of his twenty-two prose tracts may be mentioned Wit’s Trenchmour (1597), The Wil of Wit (1599), A Poste with a Packet of Mad Letters (1602-6). Sir Philip Sidney’s Ourania by N. B. (1606), A Mad World, my Masters, Adventures of Two Excellent Princes, Grimello’s Fortunes (1603), Strange News out of Divers Countries (1622), etc.; Mary Magdalen’s Lamentations (1604), and The Passion of a Discontented Mind (1601), are sometimes, but erroneously, ascribed to Breton. Footnotes References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Breton

Lascelles Abercrombie (also known as the Georgian Laureate, linking him with the “Georgian poets”; 9 January 1881– 27 October 1938) was a British poet and literary critic, one of the “Dymock poets”. Biography He was born in Ashton upon Mersey, Sale, Cheshire and educated at Malvern College, and at Owens College. Before the First World War, he lived for a time at Dymock in Gloucestershire, part of a community that included Rupert Brooke and Robert Frost. Edward Thomas visited. During these early years, he worked as a journalist, and he started his poetry writing. His first book, Interludes and Poems (1908), was followed by Mary and the Bramble (1910) and the poem Deborah, and later by Emblems of Love (1912) and Speculative Dialogues (1913). His critical works include An Essay Towards a Theory of Art (1922), and Poetry, Its Music and Meaning (1932). Collected Poems (1930) was followed by The Sale of St. Thomas (1931), a poetic drama. During World War I, he served as a munitions examiner, after which, he was appointed to the first lectureship in poetry at the University of Liverpool. In 1922 he was appointed Professor of English at the University of Leeds in preference to J. R. R. Tolkien, with whom he shared, as author of The Epic (1914), a professional interest in heroic poetry. In 1929 he moved on to the University of London, and in 1935 to the prestigious Goldsmiths’ Readership at Oxford University, where he was elected as a Fellow of Merton College. He wrote a series of works on the nature of poetry, including The Idea of Great Poetry (1925) and Romanticism (1926). He published several volumes of original verse, largely metaphysical poems in dramatic form, and a number of verse plays. Abercrombie also contributed to Georgian Poetry and several of his verse plays appeared in New Numbers (1914). His poems and plays were collected in 'Poems’ (1930). Lascelles Abercrombie died in London in 1938, aged 57, from undisclosed causes. Family He was the brother of the architect and noted town planner, Patrick Abercrombie. In 1909 he married Catherine Gwatkin (1881–1968) of Grange-over-Sands. They had 4 children, a daughter and three sons. Two of the sons achieved prominence as a phonetician David Abercrombie and a cell biologist Michael Abercrombie. A grandson, Jeffrey Cooper, produced an admirable bibliography of his grandfather, with brief but important notes, while a great-grandson is author Joe Abercrombie. Archives A collection of literary and other manuscripts relating to Abercrombie is held by Special Collections in the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds. The collection contains drafts of many of Abercrombie’s own publications and literary material; lecture notes, including those of his own lectures and some notes taken from the lectures of others, and a printed order of service for his Memorial Service in 1938. Special Collections in the Brotherton Library also holds correspondence relating to Lascelles Abercrombie and his family. Comprising 105 letters, the collection contains letters of condolence to Catherine and Ralph Abercrombie on the death of Lascelles, as well as Abercrombie family letters from various correspondents, chiefly to Ralph Abercrombie. Works * Interludes and Poems 1908 * Mary and the Bramble 1910 * Deborah * Emblems of Love 1912 * Speculative Dialogues 1913 * An Essay Towards a Theory of Art 1922 * Poetry, Its Music and Meaning 1932 * Collected Poems 1930 * The Sale of St. Thomas 1931 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lascelles_Abercrombie

Thomas Campion (sometimes Campian) (12 February 1567 – 1 March 1620) was an English composer, poet, and physician. He wrote over a hundred lute songs, masques for dancing, and an authoritative technical treatise on music. Life Campion was born in London, the son of John Campion, a clerk of the Court of Chancery, and Lucy (née Searle– daughter of Laurence Searle, one of the queen’s serjeants-at-arms). Upon the death of Campion’s father in 1576, his mother married Augustine Steward, dying soon afterwards. His stepfather assumed charge of the boy and sent him, in 1581, to study at Peterhouse, Cambridge as a “gentleman pensioner”; he left the university after four years without taking a degree. He later entered Gray’s Inn to study law in 1586. However, he left in 1595 without having been called to the bar. On 10 February 1605, he received his medical degree from the University of Caen. Campion is thought to have lived in London, practising as a physician, until his death in March 1620– possibly of the plague. He was apparently unmarried and had no children. He was buried the same day at St Dunstan-in-the-West in Fleet Street. He was implicated in the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury, but was eventually exonerated, as it was found that he had unwittingly delivered the bribe that had procured Overbury’s death. Poetry and songs The body of his works is considerable, the earliest known being a group of five anonymous poems included in the “Songs of Divers Noblemen and Gentlemen,” appended to Newman’s edition of Sir Philip Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella, which appeared in 1591. In 1595, Poemata, a collection of Latin panegyrics, elegies and epigrams was published, winning him a considerable reputation. This was followed, in 1601, by a songbook, A Booke of Ayres, with words by himself and music composed by himself and Philip Rosseter. The following year he published his Observations in the Art of English Poesie, “against the vulgar and unartificial custom of riming,” in favour of rhymeless verse on the model of classical quantitative verse. Campion’s theories on poetry were demolished by Samuel Daniel in “Defence of Rhyme” (1603). In 1607, he wrote and published a masque for the occasion of the marriage of Lord Hayes, and, in 1613, issued a volume of Songs of Mourning: Bewailing the Untimely Death of Prince Henry, set to music by John Cooper (also known as Coperario). The same year he wrote and arranged three masques: The Lords’ Masque for the marriage of Princess Elizabeth; an entertainment for the amusement of Queen Anne at Caversham House; and a third for the marriage of the Earl of Somerset to the infamous Frances Howard, Countess of Essex. If, moreover, as appears quite likely, his Two Bookes of Ayres (both words and music written by himself) belongs also to this year, it was indeed his annus mirabilis. In 1615, he published a book on counterpoint, A New Way of Making Fowre Parts in Counterpoint By a Most Familiar and Infallible Rule, a technical treatise which was for many years the standard textbook on the subject. It was included, with annotations by Christopher Sympson, in Playford’s Brief Introduction to the Skill of Musick, and two editions appear to have been published by 1660. Some time in or after 1617 appeared his Third and Fourth Booke of Ayres. In 1618 appeared the airs that were sung and played at Brougham Castle on the occasion of the King’s entertainment there, the music by George Mason and John Earsden, while the words were almost certainly by Campion. In 1619, he published his Epigrammatum Libri II. Umbra Elegiarum liber unus, a reprint of his 1595 collection with considerable omissions, additions (in the form of another book of epigrams) and corrections. Legacy Campion made a nuncupative will on 1 March 1619/20 before 'divers credible witnesses’: a memorandum was made that he did 'not longe before his death say that he did give all that he had unto Mr Phillip Rosseter, and wished that his estate had bin farre more’, and Rosseter was sworn before Dr Edmund Pope to administer as principal legatee on 3 March 1619/20. While Campion had attained a considerable reputation in his own day, in the years that followed his death his works sank into complete oblivion. No doubt this was due to the nature of the media in which he mainly worked, the masque and the song-book. The masque was an amusement at any time too costly to be popular, and during the commonwealth period it was practically extinguished. The vogue of the song-books was even more ephemeral, and, as in the case of the masque, the Puritan ascendancy, with its distaste for all secular music, effectively put an end to the madrigal. Its loss involved that of many hundreds of dainty lyrics, including those of Campion, and it was due to the work of A. H. Bullen (see bibliography), who first published a collection of the poet’s works in 1889, that his genius was recognised and his place among the foremost rank of Elizabethan lyric poets restored. Campion set little store by his English lyrics; they were to him “the superfluous blossoms of his deeper studies,” but we may thank the fates that his ideas on rhymeless versification so little affected his work. His rhymeless experiments are certainly better conceived than many others, but they lack the spontaneous grace and freshness of his other poetry, while the whole scheme was, of course, unnatural. He must have possessed a very delicate musical ear, for not one of his songs is unmusical; moreover, his ability to compose both words and music gave rise to a metrical fluidity which is one of his most characteristic features. Rarely are his rhythms uniform, while they frequently shift from line to line. His range was very great both in feeling and expression, and whether he attempts an elaborate epithalamium or a simple country ditty, the result is always full of unstudied freshness and tuneful charm. In some of his sacred pieces, he is particularly successful, combining real poetry with genuine religious fervour. Some of Campion’s works could also be quite ribald– such as “Beauty, since you so much desire”. Early dictionary writers, such as Fétis, saw Campion as a theorist. It was much later on that people began to see him as a composer. He was the writer of a poem, Cherry Ripe, which is not the later famous poem of that title but has several similarities. In popular culture Repeated reference was made to Campion in an October 2010 episode of the BBC TV series, James May’s Man Lab (BBC2), where his works are used as the inspiration for a young man trying to serenade a female colleague. This segment was referenced in the second and third series of the programme as well. Occasional mention is made of Campion ("Campian") in the comic strip 9 Chickweed Lane (i.e., 5 April 2004), referencing historical context for playing the lute. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Campion

Dorothy Mae Ann Wordsworth (25 December 1771 – 25 January 1855) was an English author, poet and diarist. She was the sister of the Romantic poet William Wordsworth, and the two were close all their lives. Wordsworth had no ambitions to be an author, and her writings consist only of series of letters, diary entries, poems and short stories. Life She was born on Christmas Day in Cockermouth, Cumberland in 1771. Despite the early deaths of both her parents, Dorothy, William and their three siblings had a happy childhood. When in 1783, their father died and the children were sent to live with various relatives. Wordsworth was sent alone to live with her aunt, Elizabeth Threlkeld, in Halifax, West Yorkshire. After she was able to reunite with William firstly at Racedown Lodge in Dorset in 1795 and afterwards (1797/98) at Alfoxden House in Somerset, they became inseparable companions. The pair lived in poverty at first; and would often beg for cast-off clothes from their friends. William wrote of her in his famous Tintern Abbey poem: Of this fair river; thou my dearest Friend, My dear, dear Friend; and in thy voice I catch The language of my former heart, and read My former pleasures in the shooting lights Of thy wild eyes [...] My dear, dear Sister! Wordsworth was a diarist and somewhat amateur poet with little interest in becoming an established writer. "I should detest the idea of setting myself up as an author," she once wrote, "give Wm. the Pleasure of it." She almost published her travel account with William to Scotland in 1803 Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland, but a publisher was not found and it would not be published until 1874. She wrote a very early account of an ascent of Scafell Pike in 1818 (perhaps predated only by Samuel Taylor Coleridge's of 1802), climbing the mountain in the company of her friend Mary Barker, Miss Barker's maid, and two local people to act as guide and porter. Dorothy's work was used in 1822 by her brother William, unattributed, in his popular guide book to the Lake District - and this was then copied by Harriet Martineau in her equally successful guide[5] (in its fourth edition by 1876), but with attribution, if only to William Wordsworth. Consequently this story was very widely read by the many visitors to the Lake District over more than half of the 19th century. She never married, and after William married Mary Hutchinson in 1802, continued to live with them. She was by now 31, and thought of herself as too old for marriage. In 1829 she fell seriously ill and was to remain an invalid for the remainder of her life. She died at eighty-three in 1855, having spent the past twenty years in, according to the biographer Richard Cavendish, "a deepening haze of senility". Her Grasmere Journal was published in 1897, edited by William Angus Knight. The journal eloquently described her day-to-day life in the Lake District, long walks she and her brother took through the countryside, and detailed portraits of literary lights of the early 19th century, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Lamb and Robert Southey, a close friend who popularised the fairytale Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Dorothy's works came to light just as literary critics were beginning to re-examine women's role in literature. The success of the Grasmere Journal led to a renewed interest in Wordsworth, and several other journals and collections of her letters have since been published. The Grasmere Journal and Wordsworth's other works revealed how vital she was to her brother's success. William relied on her detailed accounts of nature scenes and borrowed freely from her journals. For example Dorothy wrote in her journal of 5 April 1802 "... I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about & about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness & the rest tossed & reeled & danced & seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake,...". This passage is clearly brought to mind when reading William's "Daffodils", where her brother, in this poem of two years later, describes what appears to be the shared experience in the journal as his own solitary observation. References Wikipeda - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Wordsworth

Alice Christiana Gertrude Meynell (née Thompson; 11 October 1847– 27 November 1922) was an English writer, editor, critic, and suffragist, now remembered mainly as a poet. Biography Alice Christiana Gertrude Thompson was born in Barnes, London, to Thomas James and Christiana (née Weller) Thompson. The family moved around England, Switzerland, and France, but she was brought up mostly in Italy, where a daughter of Thomas from his first marriage had settled. Her father was a friend of Charles Dickens. Preludes (1875) was her first poetry collection, illustrated by her elder sister Elizabeth (the artist Lady Elizabeth Butler, 1846–1933, whose husband was Sir William Francis Butler). The work was warmly praised by Ruskin, although it received little public notice. Ruskin especially singled out the sonnet “Renunciation” for its beauty and delicacy. After Alice, the entire Thompson family converted to the Catholic Church (1868 to 1880), and her writings migrated to subjects of religious matters. This eventually led her to the Catholic newspaper publisher and editor Wilfrid Meynell (1852–1948) in 1876. A year later (in 1877) she married Meynell, and they settled in Kensington. They became the proprietors and editors of such magazines as The Pen, the Weekly Register, and Merry England, among others. Alice and Wilfrid Meynell had eight children, Sebastian, Monica, Everard, Madeleine, Viola, Vivian (who died at three months), Olivia, and Francis. Viola Meynell (1885–1956) became an author in her own right, and the youngest child Francis Meynell (1891–1975) was a poet and printer, co-founding the Nonesuch Press. She was much involved in editorial work on publications with her husband, and in her own writing, poetry and prose. She wrote regularly for The World, The Spectator, The Magazine of Art, the Scots Observer (which became the National Observer, both edited by W. E. Henley), The Tablet, The Art Journal, the Pall Mall Gazette, and The Saturday Review. The poet Francis Thompson, down and out in London and trying to recover from his opium addiction, sent the couple a manuscript. His poems were first published in Wilfrid’s Merry England, and the Meynells became a supporter of Thompson. His 1893 book Poems was a Meynell production and initiative. Another supporter of Thompson was the poet Coventry Patmore. Alice had a deep friendship with Patmore, lasting several years, which led to his becoming obsessed with her, forcing her to break with him. At the end of the 19th century, in conjunction with uprisings against the British (among them the Indians’, the Zulus’, the Boxer Rebellion, and the Muslim revolt led by Muhammad Ahmed in the Sudan), many European scholars, writers, and artists, began to question Europe’s colonial imperialism. This led the Meynells and others in their circle to speak out for the oppressed. Alice Meynell was a vice-president of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, founded by Cicely Hamilton and active 1908–19. Death and legacy After a series of illnesses, including migraine and depression, she died 27 November 1922. She is buried at Kensal Green Catholic Cemetery, London, England. There is a London Borough Council commemorative blue plaque on the front wall of the property at 47 Palace Court, Bayswater, London, W2, where she and her husband once lived.