Info

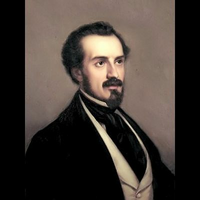

Rubén Bonifaz Nuño (Córdoba, 12 de noviembre de 1923 - México D. F., 31 de enero de 2013) fue un poeta y clasicista mexicano. Bonifaz Nuño nació en Córdoba (Veracruz) y estudió derecho en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) entre 1940 y 1947. En 1960, empezó a enseñar latín en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la UNAM y recibió un doctorado en Arte y cultura clásica en 1970. Bonifaz Nuño ha publicado traducciones de las obras de Catulo, Propercio, Lucrecio: De la natura de las cosas, Píndaro, Ovidio: Metamorfosis, Arte de amar y Remedios del amor, Lucano, Virgilio: La Eneida y las Geórgicas, Julio César: Guerra gálica, Cicerón: Acerca de los deberes y otros autores clásicos al español. Su traducción de 1973 de la Eneida fue aclamada por la crítica. Fue elegido miembro de número de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua el 19 de agosto de 1962, tomando posesión de la silla V el 30 de agosto de 1963. Bonifaz renunció al cargo el 26 de julio de 1996.1 Fue admitido en el Colegio Nacional en 1972 con el discurso de ingreso "La fundación de la ciudad".2 Fue ganador del Premio Nacional de Literatura y Lingüística en 1974. Rubén Bonifaz Nuño murió en la ciudad de México el 31 de enero de 2013. Traducciones * Eneida (1973) * Arte de amar, Remedios del amor (1975) * Metamorfosis (1979) *De la natura de las cosas (1984) *Hipólito (1998) *Ilíada (2008) Ensayos * El amor y la cólera: Cayo Valerio Catulo (1977) * Los reinos de Cintia. Sobre Propercio (1978) Poesía * La muerte del ángel (1945) * Imágenes (1953) * Los demonios y los días (1956) * El manto y la corona (1958) * Canto llano a Simón Bolívar (1958) * Fuego de pobres (1961) * Siete de espadas (1966) * El ala del tigre (1969) * La flama en el espejo (1971) * Tres poemas de antes (1978) * As de oros (1981) * El corazón de la espiral (1983) * Albur de amor (1987) * Pulsera para Lucía Méndez (1989) * Del templo de su cuerpo (1992 * Trovas del mar unido (1994). Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubén_Bonifaz_Nuño

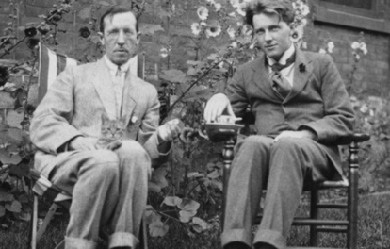

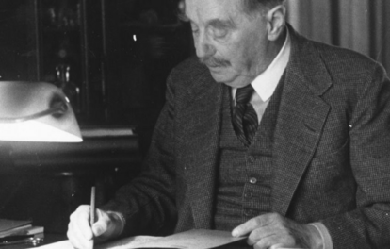

Duncan Campbell Scott (August 2, 1862– December 19, 1947) was a Canadian bureaucrat, poet and prose writer. With Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, and Archibald Lampman, he is classed as one of Canada’s Confederation Poets. Scott was a Canadian lifetime civil servant who served as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, and is better known today for advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples in that capacity. Life and legacy Scott was born in Ottawa, Ontario, the son of Rev. William Scott and Janet MacCallum. He was educated at Stanstead Wesleyan College. Early in life, he became an accomplished pianist. Scott wanted to be a doctor, but family finances were precarious, so in 1879 he joined the federal civil service. As the story goes, q:William Scott might not have money [but] he had connections in high places. Among his acquaintances was the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, who agreed to meet with Duncan. As chance would have it, when Duncan arrived for his interview, the prime minister had a memo on his desk from the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior asking for a temporary copying clerk. Making a quick decision while the serious young applicant waited in front of him, Macdonald wrote across the request: 'Approved. Employ Mr. Scott at $1.50.’ Scott "spent his entire career in the same branch of government, working his way up to the position of deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1913, the highest non-elected position possible in his department. He remained in this post until his retirement in 1932.” Scott’s father also subsequently found work in Indian Affairs, and the entire family moved into a newly built house on 108 Lisgar St., where Duncan Campbell Scott would live for the rest of his life. In 1883 Scott met fellow civil servant, Archibald Lampman. It was the beginning of an instant friendship that would continue unbroken until Lampman’s death sixteen years later.... It was Scott who initiated wilderness camping trips, a recreation that became Lampman’s favourite escape from daily drudgery and family problems. In turn, Lampman’s dedication to the art of poetry would inspire Scott’s first experiments in verse. By the late 1880s Scott was publishing poetry in the prestigious American magazine, Scribner’s. In 1889 his poems “At the Cedars” and “Ottawa” were included in the pioneering anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion. Scott and Lampman "shared a love of poetry and the Canadian wilderness. During the 1890s the two made a number of canoe trips together in the area north of Ottawa.” In 1892 and 1893, Scott, Lampman, and William Wilfred Campbell wrote a literary column, “At the Mermaid Inn,” for the Toronto Globe. "Scott... came up with the title for it. His intention was to conjure up a vision of The Mermaid Inn Tavern in old London where Sir Walter Raleigh founded the famous club whose members included Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, and other literary lights. In 1893 Scott published his first book of poetry, The Magic House and Other Poems. It would be followed by seven more volumes of verse: Labor and the Angel (1898), New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905), Via Borealis (1906), Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems (1916), Beauty and Life (1921), The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott (1926) and The Green Cloister (1935). In 1894, Scott married Belle Botsford, a concert violinist, whom he had met at a recital in Ottawa. They had one child, Elizabeth, who died at 12. Before she was born, Scott asked his mother and sisters to leave his home (his father had died in 1891), causing a long-time rift in the family. In 1896 Scott published his first collection of stories, In the Village of Viger, "a collection of delicate sketches of French Canadian life. Two later collections, The Witching of Elspie (1923) and The Circle of Affection (1947), contained many fine short stories." Scott also wrote a novel, although it was not published until after his death (as The Untitled Novel, in 1979). After Lampman died in 1899, Scott helped publish a number of editions of Lampman’s poetry. Scott “was a prime mover in the establishment of the Ottawa Little Theatre and the Dominion Drama Festival.” In 1923 the Little Theatre performed his one-act play, Pierre; it was later published in Canadian Plays from Hart House Theatre (1926). His wife died in 1929. In 1931 he married poet Elise Aylen, more than 30 years his junior. After he retired the next year, "he and Elise spent much of the 1930s and 1940s travelling in Europe, Canada and the United States.” He died in December 1947 in Ottawa at the age of 85 and is buried in Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery. Indian Affairs Prior to taking up his position as head of the Department of Indian Affairs, in 1905 Scott was one of the Treaty Commissioners sent to negotiate Treaty No. 9 in Northern Ontario. Aside from his poetry, Scott made his mark in Canadian history as the head of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932. Even before Confederation, the Canadian government had adopted a policy of assimilation under the Gradual Civilization Act 1857. One biographer of Scott states that: The Canadian government’s Indian policy had already been set before Scott was in a position to influence it, but he never saw any reason to question its assumption that the 'red’ man ought to become just like the 'white’ man. Shortly after he became Deputy Superintendent, he wrote approvingly: ‘The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government.’... Assimilation, so the reasoning went, would solve the ‘Indian problem,’ and wrenching children away from their parents to 'civilize’ them in residential schools until they were eighteen was believed to be a sure way of achieving the government’s goal. Scott... would later pat himself on the back: ‘I was never unsympathetic to aboriginal ideals, but there was the law which I did not originate and which I never tried to amend in the direction of severity.’ while Scott himself wrote: I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill. In 1920, under Scott’s direction, and with the concurrence of the major religions involved in native education, an amendment to the Indian Act made it mandatory for all native children between the ages of seven and fifteen to attend school. Attendance at a residential school was made compulsory. Although a reading of Bill 14 states that no particular kind of school was stipulated. Scott was in favour of residential schooling for aboriginal children, as he believed removing them from the influences of home and reserve would hasten the cultural and economic transformation of the whole aboriginal population. In cases where a residential school was the only kind available, residential enrollment did become mandatory, and aboriginal children were compelled to leave their homes, their families and their culture, with or without their parents’ consent. However, in 1901, 226 of the 290 Indian schools across Canada were day schools, and by 1961, the 377 day schools far outnumbered the 56 residential institutions. CBC has reported that "In all, about 150,000 aboriginal, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools." The 150,000 enrollment figure is an estimate not disputed by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, but it is not clear what percentage were “removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools.” A percentage of the residential schools were in or close by the children’s communities. Moreover, while many aboriginal parents distrusted the residential schools or preferred to raise and educate their children in a traditional manner, other parents willingly enrolled their children, partly from a belief that the schooling of the “white man” would benefit them, and partly from a knowledge that schools would provide shelter, food and clothing which dire conditions on the reserve could not provide. Harsh criticism has been leveled at Scott and the residential school system, as children who attended some of the more poorly maintained or administered schools lived in terrible conditions; in some cases the mortality rate exceeded fifty percent due to the spread of infectious disease. This situation was made worse by the federal policy that tied funding to enrollment numbers, which resulted in some schools enrolling sick children in order to boost their numbers. Echoing Scott’s desire to absorb aboriginals into the wider Canadian population, many residential and day schools strongly discouraged students from speaking their native language, and harsh punishments were administered. Corporal punishment was sometimes justified by the belief that it was the only way to “save souls”, “civilize” the native children and, in the residential schools, punish runaways who might make the school responsible for injury or death while trying to return home. Many reports of physical, sexual and psychological abuse in the residential schools have surfaced over the years. Because any kind of scandal coming out of the residential schools would have caused Indian Affairs, the churches and the government of the day much embarrassment, incidents of abuse were often discounted or covered up. When Scott retired, his “policy of assimilating the Indians had been so much in keeping with the thinking of the time that he was widely praised for his capable administration.” At the time, Scott was able to point to evidence of success in increasing enrollment and attendance, as the number of First Nations children enrolled in any school rose from 11,303 in 1912 to 17,163 in 1932. Residential school enrollment during the same period rose from 3,904 to 8,213. Actual attendance figures from all schools had also risen sharply, going from 64% of enrollment in 1920 to 75% in 1930, and Scott attributed this rise partly to Bill 14's section on compulsory attendance but also to a more positive attitude among First Nations people toward education. However, despite the encouraging statistics, Scott’s efforts to bring about assimilation through residential schools could be judged a failure, as many former students retained their language, went on to maintain and preserve their tribe’s culture, and refused to accept full Canadian citizenship when it was offered. Moreover, over the long history of the residential system, only a minority of all enrolled students went beyond the elementary grades, and many former students found themselves lacking the skills that would enable them to find employment on or off the reserve. Honours and awards Scott was honoured for his writing during and after his lifetime. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1899 and served as its president from 1921 to 1922. The Society awarded him the second-ever Lorne Pierce Medal in 1927 for his contributions to Canadian literature. In 1934 he was made a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. He also received honorary degrees from the University of Toronto (Doctor of Letters in 1922) and Queen’s University (Doctor of Laws in 1939). In 1948, the year after his death, he was designated a Person of National Historic Significance. Poetry Scott’s "literary reputation has never been in doubt. He has been well represented in virtually all major anthologies of Canadian poetry published since 1900.” In Poets of the Younger Generation (1901), Scottish literary critic William Archer wrote of Scott: He is above everything a poet of climate and atmosphere, employing with a nimble, graphic touch the clear, pure, transparent colours of a richly-furnished palette.... Though it must not be understood that his talent is merely descriptive. There is a philosophic and also a romantic strain in it... There is scarcely a poem of Mr. Scott’s from which one could not cull some memorable descriptive passage.... As a rule Mr. Scott’s workmanship is careful and highly finished. He is before everything a colourist. He paints in lines of a peculiar and vivid translucency. But he is also a metrist of no mean skill, and an imaginative thinker of no common capacity. The Government of Canada biography of him says that: Although the quality of Scott’s work is uneven, he is at his best when describing the Canadian wilderness and Indigenous peoples. Although they constitute a small portion of his total output, Scott’s widely recognized and valued 'Indian poems’ cemented his literary reputation. In these poems, the reader senses the conflict that Scott felt between his role as an administrator committed to an assimilation policy for Canada’s Native peoples and his feelings as a poet, saddened by the encroachment of European civilization on the Indian way of life. “There is not a really bad poem in the book,” literary critic Desmond Pacey said of Scott’s first book, The Magic House and Other Poems, “and there are a number of extremely good ones.” The 'extremely good ones’ include the strange, dream-like sonnets of “In the House of Dreams.” “Probably the best known poem from the collection is ‘At the Cedars,’ a grim narrative about the death of a young man and his sweetheart during a log-jam on the Ottawa River. It is crudely melodramatic,... but its style—stark understatement, irregular lines, and abrupt rhymes—makes it the most experimental poem in the book.” His next book, Labour and the Angel, “is a slighter volume than The Magic House in size and content. The lengthy title poem makes dreary reading.... Of greater interest is his growing willingness to experiment with stanza form, variations in line length, use of partial rhyme, and lack of rhyme.” Notable new poems included “The Cup” and the sonnet “The Onandaga Madonna.” But arguably “the most memorable poem in the new collection” was the fantasy, “The Piper of Arll.” One person who long remembered that poem was future British Poet Laureate John Masefield, who read “The Piper of Arll” as a teenager and years later wrote to Scott: I had never (till that time) cared very much for poetry, but your poem impressed me deeply, and set me on fire. Since then poetry has been the one deep influence in my life, and to my love of poetry I owe all my friends, and the position I now hold. New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905) revealed “a voice that is sounding ever more different from the other Confederation Poets... his dramatic power is increasingly apparent in his response to the wilderness and the lives of the people who lived there.” The poetry included “On the Way to the Mission” and the much-anthologized “The Forsaken,” two of Scott’s best-known “Indian poems.” Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems (1916) seemed “to have been cobbled together at the insistence of his publishers, who wanted a collection of his work that had not been published in any previous volume.”. The title poem was one that had won Scott, "in the Christmas Globe contest of 1908,... the prize of one hundred dollars, offered for the best poem on a Canadian historical theme.". Other notable poems in the volume include the pretty lyric “A Love Song,” the long meditation, “The Height of Land,” and the even longer “Lines Written in Memory of Edmund Morris.” Anthologist John Garvin called the last “so original, tender and beautiful that it is destined to live among the best in Canadian literature.” “In his old age, Scott would look back upon Beauty and Life (1921) as his favourite among his volumes of verse," E.K. Brown tells us, adding: “In it most of the poetic kinds he cared about are represented.” There is a great diversity, from the moving war elegy “To a Canadian Aviator Who Died For His Country in France,” to the strange, apocalyptic “A Vision.” The Green Cloister, published after Scott’s retirement, "is a travelogue of the sites he visited in Europe with Elise: Lake Como, Ravelllo, Kensington Gardens, East Gloucester, etc.—descriptive and contemplative poems by an observant tourist. Those with a Canadian setting include two Indian poems of near-melodrama—'A Scene at Lake Manitou’ and 'At Gull Lake, August 1810'—that are in stark contrast to the overall serenity of the volume." More typical is the title poem, “Chiostro Verde.” The Circle of Affection (1947) contains 26 poems Scott had written since Cloister, and several prose pieces, including his Royal Society address on “Poetry and Progress.” It includes “At Delos,” which brings to mind the poet’s approaching death: There is no grieving in the world As beauty fades throughout the years: The pilgrim with the weary heart Brings to the grave his tears. Reputation as an assimilationist In 2003, Scott’s Indian Affairs legacy came under attack from Neu and Therrien: [Scott] took a romantic interest in Native traditions, he was after all a poet of some repute (a member of the Royal Society of Canada), as well as being an accountant and a bureaucrat . He was three people rolled into one confusing and perverse soul. The poet romanticized the whole 'noble savage’ theme, the bureaucrat lamented our inability to become civilized, the accountant refused to provide funds for the so-called civilization process. In other words, he disdained all ‘living’ Natives but “extolled the freedom of the savages”. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Scott is "best known at the end of the 20th century," not for his writing, but “for advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples.” As part of their Worst Canadian poll, a panel of experts commissioned by Canada’s National History Society named Scott one of the Worst Canadians in the August 2007 issue of The Beaver. In his 2013 Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott, fabulist Mark Abley explored the paradoxes surrounding Scott’s career. Abley did not attempt to defend Scott’s work as a bureaucrat, but he showed that Scott is more than simply a one-dimensional villain. Controversy over Arc Poetry prize Arc Poetry Magazine renamed the annual “Archibald Lampman Award” (given to a poet in the National Capital Region) to the Lampman-Scott Award in recognition of Scott’s enduring legacy in Canadian poetry, with the first award under the new name given out in 2007. The winner of the 2008 award, Shane Rhodes, turned over half of the $1,500 prize money to the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health, a First Nations health centre. “Taking that money wouldn’t have been right, with what I’m writing about,” Rhodes said. The poet was researching First Nations history and found Scott’s name repeatedly referenced. In the words of a CBC News report, Rhodes felt “Scott’s legacy as a civil servant overshadows his work as a pioneer of Canadian poetry”. The editor of Arc Poetry Magazine, Anita Lahey, responded with a statement that she thought Scott’s actions as head of Indian Affairs were important to remember, but did not eclipse his role in the history of Canadian literature. “I think it matters that we’re aware of it and that we think about and talk about these things,” she said. “I don’t think controversial or questionable activities in the life of any artist or writer is something that should necessarily discount the literary legacy that they leave behind.” More recently, the magazine has stated on its website that "For the years 2007 through 2009, the Archibald Lampman Award merged with the Duncan Campbell Scott Foundation to become the Lampman-Scott Award in honour of two great Confederation Poets. This partnership came to an end in 2010, and the prize returned to its former identity as the Archibald Lampman Award for Poetry.” Publications Poetry * The Magic House and Other Poems. London: Methuen and Co. 1893. - The Magic House and Other Poems at Google Books * Labor and the Angel. Boston: Copeland & Day. 1898. – Labor and the Angel at Google Books– Labor and the Angel - Scholar’s Choice Edition at Google Books * New World Lyrics and Ballads. Toronto: Morang & Co. – New World Lyrics and Ballads at Google Books– New World Lyrics and Ballads - Scholar’s Choice Edition at Google Books * Via Borealis. Toronto: W. Tyrell. 1906. * Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems. Toronto: McClelland, Stewart & Stewart. 1916. - Lundy’s Lane and Other Poems at Google Books * To the Canadian Mothers and Three Other Poems. Toronto: Mortimer. 1917. * “After a Night of Storm” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 1 (2). 1921. * Beauty and Life. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1921. - Beauty and Life at Google Books * “Permanence” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 2 (4). 1923. * The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1926. - The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott at Google Books * “By the Sea” (PDF). Dalhousie Review 7 (1). 1927. * The Green Cloister: Later Poems. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1935. - The Green Cloister: Later Poems at Google Books * Brown, E.K., ed. (1951). Selected Poems. Toronto: Ryerson. * Clever, Glenn, ed. (1974). Duncan Campbell Scott: Selected Poetry. Ottawa: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6252-0. * Souster, Raymond; Lochhead, Douglas, eds. (1985). Powassan’s Drum: Selected Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott. Ottawa: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6211-7. Fiction * In the Village of Viger. Boston: Copeland & Day. 1896. - In the Village of Viger at Google Books * The Witching of Elspie: A Book of Stories. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1923. * The Circle of Affection and Other Pieces in Prose and Verse. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 1947. - mostly prose * Clever, Glenn, ed. (1987) [1972]. Selected Stories of Duncan Campbell Scott (revised 3rd ed.). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 978-0-7766-0183-0. * Untitled Novel (posthumously published). Moonbeam, Ontario: Penumbra. 1979 [c. 1905]. ISBN 0-920806-04-X. * Ware, Tracy, ed. (2001). “The Uncollected Short Stories of Duncan Campbell Scott”. Duncan Campbell Scott. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. Non-fiction * John Graves Simcoe. Makers of Canada, volume VII. Toronto: Morang & Co. 1905. - John Graves Simcoe at Google Books * The Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada. Volume 3. Toronto: Canadian Institute of International Affairs. 1931. * Walter J. Phillips. Toronto: Ryerson. 1947. - Walter J. Phillips at Google Books * Bourinot, Arthur S., ed. (1960). More Letters of Duncan Campbell Scott. Ottawa: Bourinot. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1979). At the Mermaid Inn: Wilfred Campbell, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott in the Globe 1892–93. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6333-5. * Macdougall, Robert L., ed. (1983). The Poet and the Critic: A Literary Correspondence Between Duncan Campbell Scott and E.K. Brown. Ottawa: Carleton University Press. ISBN 978-0-8862-9013-9. Edited * Lampman, Archibald (1900). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. The Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto: Morang & Co. * Lampman, Archibald (1925). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. Lyrics of Earth: Sonnets and Ballads. Toronto: Musson. * Lampman, Archibald (1943). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. At the Long Sault and Other New Poems. Toronto: Ryerson. * Lampman, Archibald (1947). Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. Selected Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto: Ryerson. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duncan_Campbell_Scott

Mediante mi arte busco una conexión divina que me ate, en consecuencia, a no tener miedo en caída. Me llamo Manuel, actualmente tengo 21 años, vivo en Colombia y soy un amante de la vida. Soy un enloquecido fascinado con la espléndida obra del universo. El arte en general es un canal para drenar todo lo que siento y pienso, lo que me enseña el alma del mundo y aquellas señales en el lenguaje del universo.

Gertrude Stein was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, on February 3, 1874, to wealthy German-Jewish immigrants. At the age of three, her family moved first to Vienna and then to Paris. They returned to America in 1878 and settled in Oakland, California. Her mother, Amelia, died of cancer in 1888 and her father, Daniel, died 1891. Stein attended Radcliffe College from 1893 to 1897, where she specialized in Psychology under noted psychologist William James. After leaving Radcliffe, she enrolled at the Johns Hopkins University, where she studied medicine for four years, leaving in 1901. Stein did not receive a formal degree from either institution. In 1903, Stein moved to Paris with Alice B. Toklas, a younger friend from San Francisco who would remain her partner and secretary throughout her life. The couple did not return to the United States for over thirty years. Together with Toklas and her brother Leo, an art critic and painter, Stein took an apartment on the Left Bank. Their home, 27 rue de Fleurus, soon became gathering spot for many young artists and writers including Henri Matisse, Ezra Pound, Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, and Guillaume Apollinaire. She was a passionate advocate for the "new" in art, her literary friendships grew to include writers as diverse as William Carlos Williams, Djuana Barnes, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and Ernest Hemingway. It was to Hemingway that Stein coined the phrase "the lost generation" to describe the expatriate writers living abroad between the wars. By 1913, Stein's support of cubist painters and her increasingly avant-garde writing caused a split with her brother Leo, who moved to Florence. Her first book, Three Lives, was published in 1909. She followed it with Tender Buttons in 1914. Tender Buttons clearly showed the profound effect modern painting had on her writing. In these small prose poems, images and phrases come together in often surprising ways—similar in manner to cubist painting. Her writing, characterized by its use of words for their associations and sounds rather than their meanings, received considerable interest from other artists and writers, but did not find a wide audience. Sherwood Anderson in the introduction to Geography and Plays (1922) wrote that her writing "consists in a rebuilding, and entire new recasting of life, in the city of words." Among Stein's most influential works are The Making of Americans (1925); How to Write (1931); The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), which was a best-seller; and Stanzas in Meditation and Other Poems [1929-1933] (1956). In 1934, the biographer T. S. Matthews described her as a "solid elderly woman, dressed in no-nonsense rough-spun clothes," with "deep black eyes that make her grave face and its archaic smile come alive." Stein died at the American Hospital at Neuilly on July 27, 1946, of inoperable cancer.

.jpeg)

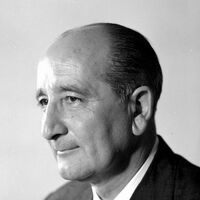

Vicente Gerbasi (Canoabo, Carabobo); 2 de junio de 1913 - Caracas, Venezuela; 28 de diciembre de 1992) fue escritor, poeta, político y diplomático venezolano, considerado el poeta contemporáneo venezolano más representativo y uno de los más brillantes exponentes de la lírica vanguardista, además de ser de los escritores más influyentes del siglo XX en Venezuela, así como de los más reconocidos. Miembro del Grupo Viernes, uno de los más notorias sociedades poéticas de Venezuela, Gerbasi no sólo lograría convertirse en su máximo exponente, sino que además se desenvolvería en una extraordinaria carrera política y diplomático, siendo miembro fundador del Partido Democrático Nacional junto con Rómulo Betancourt, Agregado Cultural de la embajada Venezolana en Bogotá, Cónsul de Venezuela en la Habana y Ginebra, Consejero Cultural de la Embajada Venezolana en Chile y Embajador de Venezuela en Haití, Israel, Dinamarca, Noruega y Polonia. Biografía Vicente Gerbasi nació el 2 de junio de 1913 en Canoabo, pequeña población del estado Carabobo, en Venezuela; hijo de los inmigrantes italianos Juan Bautista Gerbazi y Ana María Federico Pifano, quienes se habían establecido en esa región venezolana. Realizó estudios primarios y secundarios en Italia. En 1937 funda el Grupo "Viernes",conjuntamente con los poetas Pascual Venegas Filardo, Luis Fernando Alvarez, José Ramón Heredia, Oscar Rojas Jiménez, Ángel Miguel Queremel, Otto de Sola y el crítico Fernando Cabrices. Ese mismo año publica su primer libro de poesías, Vigilia del Náufrago. En 1968, Gerbasi gana el Premio Nacional de Literatura. Se desempeñó como diplomático en Colombia, donde comenzó su carrera diplomática en 1946 como Agregado Cultura luego en Cuba, Suiza y Chile. En 1959 fue designado Embajador en Haití, posteriormente en Israel (1960), luego en Dinamarca y Noruega (1964)y en Polonia (1969). Vicente Gerbasi es considerado el autor más representativo de la poesía venezolana contemporánea. En su libro de ensayos "Creación y Símbolo", el propio Gerbasi ha expresado: "En poesía las palabras no poseen un valor justo,filológico,etimológico,sino que adquieren un valor múltiple,que escapa a la lógica corriente del lenguaje". Existe en la escritura de Gerbazi una intensa investigación del lenguaje para inquirir en las peculiaridades entrañables del país. Su propósito consiste en señalar una posible identidad, pero sin fijarla en esquemas inflexibles, sino destacando sus connotaciones mágicas y su cosmogonía poética, entonces su lenguaje se hace necesario y eficaz para nombrar ese universo. En "Poema de la noche" de 1943, Gerbasi muestra estados subjetivos que alcanzan a objetivarse y concretarse en hechos reales o fenómenos naturales: "¡Haz grande mi tristeza,/misterio de la noche!/Que pase como un viento/por las sombras del campo/coronando los montes/de nieblas solitarias/tañendo en las aldeas/arpas de eternidad". Es la subjetivación que se concreta en el mundo real: "En la hierba tostada por el día, el sueño del caballo/nos rodea de flores,como el dibujo de un niño". En 1945 Gerbasi publica su libro más esencial y conocido: Mi padre el inmigrante. Se trata de un extenso poema integrado por treinta cantos basados en un mismo hilo temático: La figura mítica del padre a través de la cual opera la emoción frente al paisaje. Mi padre el inmigrante plantea enigmas metafísicos, recrea supersticiones, climas, espantos, mitos, leyendas, costumbres rurales, toda una flora y fauna fascinante y mágica. Gerbasi ha sido traducido al francés, al inglés, al italiano,al portugués, al danés, al sueco, al rumano al hebreo, al árabe y al chino. Falleció el 28 de diciembre de 1992. Obras * Vigilia del náufrago, 1937 * Bosque doliente, 1940 * Liras, 1943 * Poemas de la noche y de la tierra, 1943 * Mi padre, el inmigrante, 1945 * Tres nocturnos, 1947 * Poemas, 1947 * Los espacios cálidos, 1952 * Círculos del trueno, 1953 * La rama del relámpago, 1953 * Tirano de sombra y fuego, 1955 * Por arte del sol, 1958 * Olivos de eternidad, 1961 * Retumba como un sótano del cielo, 1977 * Edades perdidas, 1981 * Un día muy distante, 1987 * El solitario viento de las hojas, 1990 * Iniciación a la intemperie, 1990 Referencias http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vicente_Gerbasi

História de Vida La amenaza de un atentado en el barrio de Once, cercano al almacén que atendía junto a su esposa, dio un vuelco inesperado en la vida de Ramón Valdez y lo convirtió en poeta casi por casualidad. Hoy, a raíz de ese incidente adverso, es famoso por las estrofas que se cuelan en los vagones de la línea D del subte, con las que invita a los usuarios a abandonar la rutina propia del viaje. Don Ramón y Doña Elsa fueron durante más de 20 años almaceneros, pero se vieron obligados a cerrar el comercio, que se encontraba próximo a la Sociedad Argentina Hebraica, cuando el temor a que se produjeran nuevas ofensivas contra la comunidad judía en la Argentina se afianzó en la zona y llevó a los vecinos a tomar decisiones drásticas, de esas de las que luego es difícil volver atrás. "De golpe y porrazo Hebraica cerró y dejaron de venir los socios que venían a comprarme al almacén. Pasaron casi cuatro años que aguanté sin cerrar, porque vivíamos de eso, pero hubo un momento en el que no quedó nada más por hacer. Junté cosa por cosa todo lo tenía y me fui a mi casa a los 62 años, sin saber cómo seguir", relató a la nación.com el "señor de los poemas", como lo suelen llamar algunos de los viajeros frecuentes del subte. Los primeros pasos de este almacenero devenido en poeta no fueron precisamente ordenados. Más bien constituyeron ensayos hasta transformarse en el ingreso principal de la familia, sin contar la módica jubilación que había obtenido por su trabajo en el local ubicado en Sarmiento y Pasteur. Tampoco respondieron a una pasión en particular. Simplemente, se orientaron hacia un único deseo: el de poder salir adelante en medio de la bronca, el enojo y la tristeza que lo atormentaban por esos días. Una oportunidad. Un aviso publicado en un diario, que leyó una de sus hijas, acercó a Don Ramón al oficio de escribir. Se trataba de una publicidad sobre la apertura de una escuela secundaria nocturna destinada a adultos. No lo dudó. Se inscribió ese mismo día en el Colegio Evangélico Villa Devoto y recibió media beca en el arancel para poder cursar. "Estábamos todos chochos. Mis compañeros porque yo era una persona mayor y yo porque tenía adonde ir. Más que nada buscaba contención", confesó. Una de sus principales mentoras en el mundo de la poesía fue justamente la profesora de lengua del instituto. Ella fue la encargada de animarlo a contar historias sencillas, de la vida cotidiana , "de esas que le llegan a la gente", inspirándose en poemas del uruguayo Mario Benedetti, de quien hoy se confiesa como un gran admirador. Las cosas empezaban a mejorar. En las aulas del colegio nació su atracción por la escritura y comenzó a gestarse también una nueva fuente de trabajo. "Sentía la necesidad de ganarme la vida. Era lo que siempre había hecho", aseguró. Sobre ruedas. Con un cuadernillo que agrupaba sus primeros siete poemas, decidió un domingo ir a probar suerte, en compañía de su familia, a Parque Centenario. "Empecé a repartirlos a orillas del lago. Se los daba a la gente para que los leyera y después pasaba a recogerlos. Ese domingo me gané 6 pesos, que en ese momento era un montón. Significaba el vino, el tomate y los fideos", recordó, mientras una sonrisa cargada de picardía y satisfacción aparecía en su cara. Pero la espera entre un fin de semana y el siguiente para la venta se hacía ardua y había que mantener la casa. Y fue ahí cuando se acordó de haber visto a un chico en el subte que vendía poemas: "Y pensé: ¿Por qué no?". Tímidamente Ramón describió: "Vivía en Corrientes y Medrano, pero me fui al subte que quedaba más lejos mi casa, el de Retiro, donde nadie me conocía. Cuando vi venir el primer subte, dije: «No, este viene muy vacío, me quedo un poquito más». Después pasó otro, pero tampoco subí porque venía muy lleno. Lo que pasaba en realidad es que tenía «chucho», una vergüenza terrible. Era muy difícil exponerse. Sentía que estaba mendigando. Pero después arranqué". Sus seguidores. Hoy, lejos de las góndolas o de la caja registradora del almacén, el poeta del subte disfruta de las muestras diarias de cariño que recibe de los usuarios del servicio, pero también de las que le envían los admiradores de su obra desde Colombia, México y España, para felicitarlo por su ejemplo de esfuerzo y dedicación a los casi 75 años. "Me generan la alegría más grande y me levantan el ánimo todos los días", indicó agradecido tras "haber encontrado su lugar en el mundo". Poema del Olvido Tú puedes olvidar y los recuerdos Se pegan a mi piel como un castigo. Tú puedes olvidar, yo sólo vivo Añorando el querer que se ha perdido. Tú puedes olvidar y en cada noche Mil vueltas yo me doy buscando olvido. Tú puedes olvidar. ¡Ay si pudiera! Olvidar como tú... sin un suspiro. Referencias http://sociedadedospoetasamigos.blogspot.com.es/2010/04/don-ramon-de-almagro-poeta-argentino.html

George Crabbe (/kræb/; 24 December 1754– 3 February 1832) was an English poet, surgeon, and clergyman. He is best known for his early use of the realistic narrative form and his descriptions of middle and working-class life and people. In the 1770s, Crabbe began his career as a doctor’s apprentice, later becoming a surgeon. In 1780, he travelled to London to make a living as a poet. After encountering serious financial difficulty and being unable to have his work published, he wrote to the statesman and author Edmund Burke for assistance. Burke was impressed enough by Crabbe’s poems to promise to help him in any way he could. The two became close friends and Burke helped Crabbe greatly both in his literary career and in building a role within the church. Burke introduced Crabbe to the literary and artistic society of London, including Sir Joshua Reynolds and Samuel Johnson, who read The Village before its publication and made some minor changes. Burke secured Crabbe the important position of Chaplain to the Duke of Rutland. Crabbe served as a clergyman in various capacities for the rest of his life, with Burke’s continued help in securing these positions. He developed friendships with many of the great literary men of his day, including Sir Walter Scott, whom he visited in Edinburgh, and William Wordsworth and some of his fellow Lake Poets, who frequently visited Crabbe as his guests. Lord Byron described him as “nature’s sternest painter, yet the best.” Crabbe’s poetry was predominantly in the form of heroic couplets, and has been described as unsentimental in its depiction of provincial life and society. The modern critic Frank Whitehead wrote that “Crabbe, in his verse tales in particular, is an important–indeed, a major–poet whose work has been and still is seriously undervalued.” Crabbe’s works include The Village (1783), Poems (1807), The Borough (1810), and his poetry collections Tales (1812) and Tales of the Hall (1819). Biography Early life Crabbe was born in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, the eldest child of George Crabbe Sr. The elder George Crabbe had been a teacher at a village school in Orford, Suffolk, and later in Norton, near Loddon, Norfolk; he later became a tax collector for salt duties, a position that his own father had held. As a young man he married an older widow named Craddock, who became the mother of his six children: George, his brothers Robert, John, and William, his sister Mary, and another sister who died as an infant. George Jr. spent his first 25 years close to his birthplace. He showed an aptitude for books and learning at an early age. He was sent to school while still very young, and developed an interest in the stories and ballads that were popular among his neighbors. His father owned a few books, and used to read passages from John Milton and from various 18th-century poets to his family. He also subscribed to a country magazine called Martin’s Philosophical Magazine, giving the “poet’s corner” section to George. The senior Crabbe had interests in the local fishing industry, and owned a fishing boat; he had contemplated raising his son George to be a seaman, but soon found that the boy was unsuited to such a career. George’s father respected his son’s interest in literature, and George was sent first to a boarding-school at Bungay near his home, and a few years later to a more important school at Stowmarket, where he gained an understanding of mathematics and Latin, and a familiarity with the Latin classics. His early reading included the works of William Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, who had a great influence on George’s future works, Abraham Cowley, Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser. He spent three years at Stowmarket before leaving school to find a physician to be apprenticed to, as medicine had been settled on as his future career. In 1768 he was apprenticed to a local doctor at Wickhambrook, near Bury St Edmunds. This doctor practiced medicine while also keeping a small farm, and George ended up doing more farm labour and errands than medical work. In 1771 he changed masters and moved to Woodbridge, where he remained until 1775. While at Woodbridge he joined a small club of young men who met at an inn for evening discussions. Through his contacts at Woodbridge he met his future wife, Sarah Elmy. Crabbe called her “Mira”, later referring to her by this name in some of his poems. During this time he began writing poetry. In 1772, a lady’s magazine offered a prize for the best poem on the subject of hope, which Crabbe won. The same magazine printed other short pieces of Crabbe’s throughout 1772. They were signed “G. C., Woodbridge,” and included some of his lyrics addressed to Mira. Other known verses written while he was at Woodbridge show that he made experiments in stanza form modeled on the works of earlier English poets, but only showed some slight imitative skill. 1775 to 1785 His first major work, a satirical poem of nearly 400 lines in Pope’s couplet form entitled Inebriety, was self-published in 1775. Crabbe later said of the poem, which received little or no attention at the time, “Pray let not this be seen... there is very little of it that I’m not heartily ashamed of.” By this time he had completed his medical training and had returned home to Aldeburgh. He had intended to go on to London to study at a hospital, but he was forced through low finances to work for some time as a local warehouseman. He eventually travelled to London in 1777 to practice medicine, returning home in financial difficulty after a year. Crabbe continued to practice as a surgeon after returning to Aldeburgh, but as his surgical skills remained deficient, he attracted only the poorest patients, and his fees were small and undependable. This hurt his chances of an early marriage, but Sarah stayed devoted to him. In late 1779 he decided to move to London and see if he could make it as a poet, or, if that failed, as a doctor. He moved to London in April 1780, where he had little success, and by the end of May he had been forced to pawn some of his possessions, including his surgical instruments. He composed a number of works but was refused publication. He wrote several letters seeking patronage, but these were also refused. In June Crabbe witnessed instances of mob violence during the Gordon Riots, and recorded them in his journal. He was able to publish a poem at this time entitled The Candidate, but it was badly received by critics. He continued to rack up debts that he had no way of paying, and his creditors pressed him. He later told Walter Scott and John Gibson Lockhart that “during many months when he was toiling in early life in London he hardly ever tasted butchermeat except on a Sunday, when he dined usually with a tradesman’s family, and thought their leg of mutton, baked in the pan, the perfection of luxury.” In early 1781 he wrote a letter to Edmund Burke asking for help, in which he included samples of his poetry. Burke was swayed by Crabbe’s letter and a subsequent meeting with him, giving him money to relieve his immediate wants, and assuring him that he would do all in his power to further Crabbe’s literary career. Among the samples that Crabbe had sent to Burke were pieces of his poems The Library and The Village. A short time after their first meeting Burke told his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds that Crabbe had “the mind and feelings of a gentleman.” Burke gave Crabbe the footing of a friend, admitting him to his family circle at Beaconsfield. There he was given an apartment, supplied with books, and made a member of the family. The time he spent with Burke and his family helped by enlarging his knowledge and ideas, and introducing him to many new and valuable friends including Charles James Fox and Samuel Johnson. He completed his unfinished poems and revised others with the help of Burke’s criticism. Burke helped him have his poem, The Library, published anonymously in June 1781, by a publisher that had previously refused some of his work. The Library was greeted with modest praise from critics, and slight public appreciation. Through their friendship, Burke discovered that Crabbe was more suited to be a clergyman than a surgeon. Crabbe had a good knowledge of Latin and an evident natural piety, and was well read in the scriptures. He was ordained to the curacy of his native town on 21 December 1781 through Burke’s recommendation. He returned to live in Aldeburgh with his sister and father, his mother having died in his absence. Crabbe was surprised to find that he was poorly treated by his fellow townsmen, who resented his rise in social class. With Burke’s help, Crabbe was able to leave Aldeburgh to become chaplain to the Duke of Rutland at Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire. This was an unusual move on Burke’s part, as this kind of preferment would usually have been given to a family member or personal friend of the Duke or through political interest. Crabbe’s experience as Chaplain at Belvoir was not altogether happy. He was treated with kindness by the Duke and Duchess, but his slightly unpolished manners and his position as a literary dependent made his relations with others in the Duke’s house difficult, especially the servants. However, the Duke and Duchess and many of their noble guests shared an interest in Crabbe’s literary talent and work. During his time there, his poem The Village was published in May 1783, achieving popularity with the public and critics. Samuel Johnson said of the poem in a letter to Reynolds “I have sent you back Mr. Crabbe’s poem, which I read with great delight. It is original, vigorous, and elegant.” Johnson’s friend and biographer James Boswell also praised The Village. It was said at the time of publication that Johnson had made extensive changes to the poem, but Boswell responded by saying that “the aid given by Johnson to the poem, as to The Traveller and Deserted Village of Goldsmith, were so small as by no means to impair the distinguished merit of the author.” Crabbe was able to keep up his friendships with Burke, Reynolds, and others during the Duke’s occasional visits to London. He visited the theatre, and was impressed with the actresses Sarah Siddons and Dorothea Jordan. Around this time it was decided that, as Chaplain to a noble family, Crabbe was in need of a college degree, and his name was entered on the boards of Trinity College, Cambridge, through the influence of Bishop Watson of Llandaff, so that Crabbe could obtain a degree without residence. This was in 1783, but almost immediately afterwards he received an LL.B. degree from the Archbishop of Canterbury. This degree allowed Crabbe to be given two small livings in Dorsetshire, Frome St Quintin and Evershot. This promotion does not seem to have interfered with Crabbe’s residence at Belvoir or in London; it is likely that curates were placed in these situations. On the strength of these preferments and a promise of future assistance from the Duke, Crabbe and Sarah Elmy were married in December 1783, in the parish church of Beccles, where Miss Elmy’s mother lived, and a few weeks later went to live together at Belvoir Castle. In 1784 the Duke of Rutland became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. It was decided that Crabbe was not to be on the Duke’s staff in Ireland, though the two men parted as close friends. The young couple stayed on at Belvoir for nearly another eighteen months before Crabbe accepted a vacant curacy in the neighbourhood, that of Stathern in Leicestershire, where Crabbe and his wife moved in 1785. A child had been born to them at Belvoir, dying only hours after birth. During the following four years at Stathern they had three other children; two sons, George and John, in 1785 and 1787, and a daughter in 1789, who died in infancy. Crabbe later told his children that his four years at Stathern were the happiest of his life. 1785 to 1810 In October 1787 the Duke of Rutland died at the Vice-Regal Lodge in Dublin, after a short illness, at the early age of 35. Crabbe assisted at the funeral at Belvoir. The Duchess, anxious to have their former chaplain close by, was able to get Crabbe the two livings of Muston, Leicestershire, and Allington, Lincolnshire, in exchange for his old livings. Crabbe brought his family to Muston in February 1789. His connection with the two livings lasted for over 25 years, but during 13 of these years he was a non-resident. He stayed three years at Muston. Another son, Edmund, was born in 1790. In 1792, through the death of one of Sarah’s relations and soon after of her older sister, the Crabbe family came into possession of an estate in Parham, which removed all of their financial worries. Crabbe soon moved his family to this estate. Their son William was born the same year. Crabbe’s life at Parham was not happy. The former owner of the estate had been very popular for his hospitality, while Crabbe’s lifestyle was much more quiet and private. His solace here was the company of his friend Dudley Long North and his fellow Whigs who lived nearby. Crabbe soon sent his two sons George and John to school in Aldeburgh. After four years at Parham, the Crabbes moved to a home in Great Glemham, Suffolk, placed at his disposal by Dudley North. The family remained here for four or five years. In 1796 their third son, Edmund died at the age of six. This was a heavy blow to Sarah who began suffering from a nervous disorder from which she never recovered. Crabbe, a devoted husband, tended her with exemplary care until her death in 1813. Robert Southey, writing about Crabbe to his friend, Neville White, in 1808, said “It was not long before his wife became deranged, and when all this was told me by one who knew him well, five years ago, he was still almost confined in his own house, anxiously waiting upon this wife in her long and hopeless malady. A sad history! It is no wonder that he gives so melancholy a picture of human life.” During his time at Glemham, Crabbe composed several novels, none of which were published. After Glemham, Crabbe moved to the village of Rendham in Suffolk, where he stayed until 1805. His poem The Parish Register was all but completed while at Rendham, and The Borough was also begun. 1805 was the last year of Crabbe’s stay in Suffolk, and it was made memorable in literature by the appearance of the Lay of the Last Minstrel by Walter Scott. Crabbe first saw it in a bookseller’s shop in Ipswich, read it nearly through while standing at the counter, and pronounced that a new and great poet had appeared. In October 1805, Crabbe returned with his wife and two sons to the parsonage at Muston. He had been absent for nearly 13 years, of which four had been spent at Parham, five at Great Glemham, and four at Rendham. In September 1807, Crabbe published a new volume of poems. Included in this volume were The Library, The Newspaper, and The Village; the principal new poem was The Parish Register, to which were added Sir Eustace Grey and The Hall of Justice. The volume was dedicated to Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, nephew and sometime ward of Charles James Fox. An interval of 22 years had passed since Crabbe’s last appearance as an author, and he explained in the preface to this volume the reasons for this lapse as being his higher calling as a clergyman and his slow progress in poetical ability. This volume led to Crabbe’s general acceptance as an important poet. Four editions were issued during the following year and a half, the fourth appearing in March 1809. The reviews were unanimous in approval, headed by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review. In 1809 Crabbe sent a copy of his poems in their fourth edition to Walter Scott, who acknowledged them in a friendly reply. Scott told Crabbe “how for more than twenty years he had desired the pleasure of a personal introduction to him, and how, as a lad of eighteen, he had met with selections from The Village and The Library in The Annual Register.” This exchange of letters led to a friendship that lasted for the rest of their lives, both authors dying in 1832. Crabbe’s favorite among Scott’s “Waverley” novels was The Heart of Midlothian. The success of The Parish Register in 1807 encouraged Crabbe to proceed with a far longer poem, which he had been working on for several years. The Borough was begun at Rendham in Suffolk in 1801, continued at Muston after his return in 1805, and finally completed during a long visit to Aldeburgh in the autumn of 1809. It was published in 1810. In spite of its defects, The Borough was an outright success. The poem appeared in February 1810, and went through six editions in the next six years. When he visited London a few years later and was received with general welcome in the literary world, he was very surprised. “In my own village,” he told James Smith, “they think nothing of me.” The three years following the publication of The Borough were especially lonely for him. He did have his two sons, George and John, with him; they had both passed through Cambridge, one at Trinity and the other at Caius, and were now clergymen themselves, each holding a curacy in the neighbourhood, enabling them to live under the parental roof, but Mrs. Crabbe’s health was now very poor, and Crabbe had no daughter or female relative at home to help him with her care. Later life Crabbe’s next volume of poetry, Tales was published in the summer of 1812. It received a warm welcome from the poet’s admirers, and was favorably reviewed by Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review and is considered to be his masterpiece. In the summer of 1813, Mrs. Crabbe felt well enough to want to see London again, and the father and mother and two sons spent nearly three months in rooms in a hotel. Crabbe was able to visit Dudley North and some of his other old friends, and to visit and help the poor and distressed, remembering his own want and misery in the great city thirty years earlier. The family returned to Muston in September, and Mrs. Crabbe died at the end of October at the age of 63. Within days of his wife’s death Crabbe fell seriously ill, and was in danger of dying. He rallied, however, and returned to the duties of his parish. In 1814, he became Rector of Trowbridge in Wiltshire, a position given to him by the new Duke of Rutland. He remained at Trowbridge for the rest of his life. His two sons followed him, as soon as their existing engagements allowed them to leave Leicestershire. The younger, John, who married in 1816, became his father’s curate, and the elder, who married a year later, became curate at Pucklechurch, also nearby. Crabbe’s reputation as a poet continued to grow in these years. His growing reputation soon made him a welcome guest in many houses to which his position as vicar of Trowbridge might not have admitted him. Nearby was the poet William Lisle Bowles, who introduced Crabbe to the noble family at Bowood House, home of the Marquess of Lansdowne, who was always ready to welcome those distinguished in literature and the arts. It was at Bowood House that Crabbe first met the poet Samuel Rogers, who became a close friend and had an influence on Crabbe’s poetry. In 1817, on the recommendation of Rogers, Crabbe stayed in London from the middle of June to the end of July in order to enjoy the literary society of the capital. While there he met Thomas Campbell, and through him and Rogers was introduced to his future publisher John Murray. In June 1819, Crabbe published his collection Tales of the Hall. The last 13 years of Crabbe’s life were spent at Trowbridge, varied by occasional visits among his friends at Bath and the surrounding neighbourhood, and by yearly visits to his friend Samuel Hoare Jr in Hampstead. From here it was easy to visit his literary friends in London, while William Wordsworth, Southey, and others occasionally stayed with the family. Around 1820 Crabbe began suffering from frequent severe attacks of neuralgia, and this illness, together with his age, made him less and less able to travel to London. In the spring of 1822, Crabbe met Walter Scott for the first time in London, and promised to visit him in Scotland in the fall. He kept this promise during George IV’s visit to Edinburgh, in the course of which the King met Scott and the poet was given a wine glass from which the King had drunk. Scott returned from the meeting with the King to find Crabbe at his home. As John Gibson Lockhart related in his Life of Sir Walter Scott, Scott entered the room that had been set aside for Crabbe, wet and hurried, and embraced Crabbe with brotherly affection. The royal gift was forgotten—the ample skirt of the coat within which it had been packed, and which he had hitherto held cautiously in front of his person, slipped back to its more usual position—he sat down beside Crabbe, and the glass was crushed to atoms. His scream and gesture made his wife conclude that he had sat down on a pair of scissors, or the like: but very little harm had been done except the breaking of the glass. Later in 1822, Crabbe was invited to spend Christmas at Belvoir Castle, but was unable to make the trip because of the winter weather. While at home, he continued to write a large amount of poetry, leaving 21 manuscript volumes at his death. A selection from these formed the Posthumous Poems, published in 1834. Crabbe continued to visit at Hampstead throughout the 1820s, often meeting the writer Joanna Baillie and her sister Agnes. In the autumn of 1831, Crabbe visited the Hoares. He left them in November, expressing his pain and sadness at leaving in a letter, feeling that it might be the last time he saw them. He left Clifton in November, and went direct to his son George, at Pucklechurch. He was able to preach twice for his son, who congratulated him on the power of his voice, and other encouraging signs of strength. “I will venture a good sum, sir,” he said, “that you will be assisting me ten years hence.” “Ten weeks” was Crabbe’s answer, and the prediction was right almost to the day. After a short time at Pucklechurch, Crabbe returned to his home at Trowbridge. Early in January he reported continued drowsiness, which he felt was a sign of increasing weakness. Later in the month he was prostrated by a severe cold. Other complications arose, and it soon became apparent that he would not live much longer. He died on 3 February 1832, with his two sons and his faithful nurse by his side. Poetry Crabbe’s poetry was predominantly in the form of heroic couplets, and has been described as unsentimental in its depiction of provincial life and society. John Wilson wrote that “Crabbe is confessedly the most original and vivid painter of the vast varieties of common life that England has ever produced;” and that “In all the poetry of this extraordinary man, we see a constant display of the passions as they are excited and exacerbated by the customs, laws, and institutions of society.” The Cambridge History of English Literature saw Crabbe’s importance to be more in his influence than in his works themselves: “He gave the poetry of nature new worlds to conquer (rather than conquered them himself) by showing that the world of plain fact and common detail may be material for poetry”. Although Augustan literature played an important role in Crabbe’s life and poetical career, his body of work is unique and difficult to classify. His best works are an original achievement in a new realistic poetical form. The major factor in Crabbe’s evolving from the Augustan influence to his use of realistic narrative was the changing readership of the late 18th–early 19th century. In the mid-18th century, literature was confined to the aristocratic and highly educated class; with the rise of the middle class at the turn of the 19th century, which came with a growing number of provincial papers, the heightening in production of books in weekly installments, and the establishment of circulating libraries, the need for literature was spread throughout the middle class. Narrative poetry was not a generally accepted mode in Augustan literature, making the narrative form of Crabbe’s mature works an innovation. This was due to some extent to the rise in popularity of the novel in the late 18th–early 19th century. Another innovation is the attention that Crabbe pays to details, both in description and characterization. Augustan critics had espoused the view that minute details should be avoided in favor of generality. Crabbe also broke with Augustan tradition by not dealing with exalted and aristocratic characters, but rather choosing people from middle and working-class society. Poor characters like Crabbe’s often anthologized “Peter Grimes” from The Borough would have been completely unacceptable to Augustan critics. In this way, Crabbe created a new way of presenting life and society in poetry. Criticism Wordsworth predicted that Crabbe’s poetry would last “from its combined merits as truth and poetry fully as long as anything that has been expressed in verse since it first made its appearance”, though on another occasion, according to Henry Crabb Robinson, he “blamed Crabbe for his unpoetical mode of considering human nature and society.” This last opinion was also held by William Hazlitt, who complained that Crabbe’s characters “remind one of anatomical preservations; or may be said to bear the same relation to actual life that a stuffed cat in a glass-case does to the real one purring on the hearth.” Byron, besides what he said in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, declared, in 1816, that he considered Crabbe and Coleridge “the first of these times in point of power and genius.” Byron had felt that English poetry had been steadily on the decline since the depreciation of Pope, and pointed to Crabbe as the last remaining hope of a degenerate age. Other admirers included Jane Austen, Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Sir Walter Scott, who used numerous quotes from Crabbe’s poems in his novels. During Scott’s final illness, Crabbe was the last writer he asked to have read to him. Lord Byron admired Crabbe’s poetry, and called him “nature’s sternest painter, yet the best”. According to critic Frank Whitehead, “Crabbe, in his verse tales in particular, is an important—indeed, a major—poet whose work has been and still is seriously undervalued.” His early poems, which were non-narrative essays in poetical form, gained him the approval of literary men like Samuel Johnson, followed by a period of 20 years in which he wrote much, destroying most of it, and published nothing. In 1807, he published his volume Poems which started off the new realistic narrative method that characterized his poetry for the rest of his career. Whitehead states that this narrative poetry, which occupies the bulk of Crabbe’s output, should be at the center of modern critical attention. Q. D. Leavis said of Crabbe: “He is (or ought to be—for who reads him?) a living classic.” His classic status was also supported by T. S. Eliot in an essay on the poetry of Samuel Johnson in which Eliot grouped Crabbe together favorably with Johnson, Pope, and several other poets. Eliot said that “to have the virtues of good prose is the first and minimum requirement of good poetry.” Critic Arthur Pollard believes that Crabbe definitely met this qualification. Critic William Caldwell Roscoe, answering William Hazlitt’s question of why Crabbe hadn’t in fact written prose rather than verse said “have you ever read Crabbe’s prose? Look at his letters, especially the later ones, look at the correct but lifeless expression of his dedications and prefaces—then look at his verse, and you will see how much he has exceeded 'the minimum requirement of good poetry’.” Critic F. L. Lucas summed up Crabbe’s qualities: "naïve, yet shrewd; straightforward, yet sardonic; blunt, yet tender; quiet, yet passionate; realistic, yet romantic." Crabbe, who is seen as a complicated poet, has been and often still is dismissed as too narrow in his interests and in his way of responding to them in his poetry. “At the same time as the critic is making such judgments, he is all too often aware that Crabbe, nonetheless, defies classification,” says Pollard. Pollard has attempted to examine the negative views of Crabbe and the reasons for limited readership since his lifetime: "Why did Crabbe’s 'realism’ and his discovery of what in effect was the short story in verse fail to appeal to the fiction-dominated Victorian age? Or is it that somehow psychological analysis and poetry are uneasy bedfellows? But then why did Browning succeed and Crabbe descend to the doldrums or to the coteries of admiring enthusiasts? And why have we in this century (the 20th century) failed to get much nearer to him? Does this mean that each succeeding generation must struggle to find his characteristic and essential worth? FitzGerald was only one of many among those who would make 'cullings from’ or 'readings in’ Crabbe. The implications of such selection are clearly that, though much has vanished, much deserves to remain.” Entomology Crabbe was known as a coleopterist and recorder of beetles, and is credited for discovering the first specimen of Calosoma sycophanta L. to be recorded from Suffolk. He published an essay on the Natural History of the Vale of Belvoir in John Nichols’s, Bibliotheca Topographia Britannica, VIII, Antiquities in Leicestershire, 1790. It includes a very extensive list of local coleopterans, and references more than 70 species. Bibliography * Inebriety (published 1775) * The Candidate (published 1780) * The Library (published 1781) * The Village (published 1782) * The Newspaper (published 1785) * Poems (published 1807) * The Borough (published 1810) * Tales in Verse (published 1812) * Tales of the Hall (published 1819) * Posthumous Tales (published 1834) Adaptations * Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes is based on The Borough. Britten also set an extract from The Borough as the third of his Five Flower Songs, op. 47. Charles Lamb’s verse play The Wife’s Trial; or, The Intruding Widow, written in 1827 and published the following year in Blackwood’s Magazine, was based on Crabbe’s tale “The Confidant”. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Crabbe

Desde un desde, la empatía se alejo de mi, la poesía llegó como un anzuelo de palabras para este humilde poeta y soñador, el siguiente escrito no es un desvelo, es el velo de una sonrisa tras un muro de ansiedades. Te invito a que conocer un poco de mi sufrimiento tan hermoso como brusco, muchos gritos de mi corazón y miles de lagrimas desbordadas mis lágrimas recorriendo mi rostro con esperanza y temblores. Contacto personal: [email protected] Blogger: https://juandiegogomezmorales.blogspot.com

Born on July 21, 1899, in Garrettsville, Ohio, Harold Hart Crane was a highly anxious and volatile child. He began writing verse in his early teenage years, and though he never attended college, read regularly on his own, digesting the works of the Elizabethan dramatists and poets—Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Donne—and the nineteenth-century French poets—Vildrac, Laforgue, and Rimbaud. His father, a candy manufacturer, attempted to dissuade him from a career in poetry, but Crane was determined to follow his passion to write. Living in New York City, he associated with many important figures in literature of the time, including Allen Tate, Katherine Anne Porter, E. E. Cummings, and Jean Toomer, but his heavy drinking and chronic instability frustrated any attempts at lasting friendship. An admirer of T. S. Eliot, Crane combined the influences of European literature and traditional versification with a particularly American sensibility derived from Walt Whitman. His major work, the book-length poem, The Bridge, expresses in ecstatic terms a vision of the historical and spiritual significance of America. Like Eliot, Crane used the landscape of the modern, industrialized city to create a powerful new symbolic literature. Hart Crane committed suicide in 1932, at the age of thirty-three, by jumping from the deck of a steamship sailing back to New York from Mexico. A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Poetry The Complete Poems and Selected Letters and Prose (1966) The Bridge (1930) White Buildings (1926) Prose Letters (1952) References Poets.org – http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/233