John Bunyan (/ˈbʌnjən/; baptised 30 November 1628– 31 August 1688) was an English writer and Baptist preacher best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress. In addition to The Pilgrim’s Progress, Bunyan wrote nearly sixty titles, many of them expanded sermons. Bunyan came from the village of Elstow, near Bedford. He had some schooling and at the age of sixteen joined the Parliamentary army during the first stage of the English Civil War. After three years in the army he returned to Elstow and took up the trade of tinker, which he had learned from his father. He became interested in religion after his marriage, attending first the parish church and then joining the Bedford Meeting, a nonconformist group in Bedford, and becoming a preacher. After the restoration of the monarch, when the freedom of nonconformists was curtailed, Bunyan was arrested and spent the next twelve years in jail as he refused to undertake to give up preaching. During this time he wrote a spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, and began work on his most famous book, The Pilgrim’s Progress, which was not published until some years after his release. Bunyan’s later years, in spite of another shorter term of imprisonment, were spent in relative comfort as a popular author and preacher, and pastor of the Bedford Meeting. He died aged 59 after falling ill on a journey to London and is buried in Bunhill Fields. The Pilgrim’s Progress became one of the most published books in the English language; 1,300 editions having been printed by 1938, 250 years after the author’s death. He is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 30 August, and on the liturgical calendar of the United States Episcopal Church on 29 August. Some other churches of the Anglican Communion, such as the Anglican Church of Australia, honour him on the day of his death (31 August). Early life John Bunyan was born in 1628 to Thomas and Margaret Bunyan at Bunyan’s End in the parish of Elstow, Bedfordshire. Bunyan’s End is located about half-way between the hamlet of Harrowden (one mile south-east of Bedford) and Elstow High Street. Bunyan’s date of birth is not known, but he was baptised on 30 November 1628, the baptismal entry in the parish register reading "John the sonne of Thomas Bunnion Jun., the 30 November". The name Bunyan was spelt in many different ways (there are 34 variants in Bedfordshire Record Office) and had its origins in the Norman-French name Buignon. There had been Bunyans in north Bedfordshire since at least 1199. Bunyan’s father was a brazier or tinker who travelled around the area mending pots and pans, and his grandfather had been a chapman or small trader. The Bunyans also owned land in Elstow, so Bunyan’s origins were not quite as humble as he suggested in his autobiographical work Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners when he wrote that his father’s house was “of that rank that is meanest and most despised in the country”. As a child Bunyan learnt his father’s trade of tinker and was given some rudimentary schooling. In Grace Abounding Bunyan recorded few details of his upbringing, but he did note how he picked up the habit of swearing (from his father), suffered from nightmares, and read the popular stories of the day in cheap chap-books. In the summer of 1644 Bunyan lost both his mother and his sister Margaret. That autumn, shortly before or after his sixteenth birthday, Bunyan enlisted in the Parliamentary army when an edict demanded 225 recruits from the town of Bedford. There are few details available about his military service, which took place during the first stage of the English Civil War. A muster roll for the garrison of Newport Pagnell shows him as private “John Bunnian”. In Grace Abounding, he recounted an incident from this time, as evidence of the grace of God: “When I was a Soldier I, with others were drawn out to go to such a place to besiege it; But when I was just ready to go, one of the company desired to go in my room, to which, when I had consented, he took my place; and coming to the siege, as he stood Sentinel, he was shot into the head with a Musket bullet and died.” Bunyan’s army service provided him with a knowledge of military language which he then used in his book The Holy War, and also exposed him to the ideas of the various religious sects and radical groups he came across in Newport Pagnell. The garrison town also gave him opportunities to indulge in the sort of behaviour he would later confess to in Grace Abounding: “So that until I came to the state of Marriage, I was the very ringleader of all the Youth that kept me company, in all manner of vice and ungodliness”. Bunyan spent nearly three years in the army, leaving in 1647 to return to Elstow and his trade as a tinker. His father had remarried and had more children and Bunyan moved from Bunyan’s End to a cottage in Elstow High Street. Marriage and conversion Within two years of leaving the army, Bunyan married. The name of his wife and the exact date of his marriage are not known, but Bunyan did recall that his wife, a pious young woman, brought with her into the marriage two books that she had inherited from her father: Arthur Dent’s Plain Man’s Pathway to Heaven and Lewis Bayly’s Practice of Piety. He also recalled that, apart from these two books, the newly-weds possessed little: “not having so much household-stuff as a Dish or a Spoon betwixt us both”. The couple’s first daughter, Mary, was born in 1650, and it soon became apparent that she was blind. They would have three more children, Elizabeth, Thomas and John. By his own account, Bunyan had as a youth enjoyed bell-ringing, dancing and playing games including on Sunday, thought by many to be the Sabbath, which was forbidden by the Puritan regime. One Sunday the vicar of Elstow preached a sermon against Sabbath breaking, and Bunyan took this sermon to heart. That afternoon, as he was playing tip-cat (a game in which a small piece of wood is hit with a bat) on Elstow village green, he heard a voice from the heavens “Wilt thou leave thy sins, and go to Heaven? Or have thy sins, and go to Hell?” The next few years were a time of intense spiritual conflict for Bunyan as he struggled with his doubts and fears over religion and guilt over what he saw as his state of sin. During this time Bunyan, whilst on his travels as a tinker, happened to be in Bedford and pass a group of women who were talking about spiritual matters on their doorstep. The women were in fact some of the founding members of the Bedford Free Church or Meeting and Bunyan, who had been attending the parish church of Elstow, was so impressed by their talk that he joined their church. At that time the nonconformist group was meeting in St John’s church in Bedford under the leadership of former Royalist army officer John Gifford. At the instigation of other members of the congregation Bunyan began to preach, both in the church and to groups of people in the surrounding countryside. In 1656, having by this time moved his family to St Cuthbert’s Street in Bedford, he published his first book, Gospel Truths Opened, which was inspired by a dispute with Quakers. In 1658 Bunyan’s wife died, leaving him with four small children, one of them blind. A year later he married an eighteen-year-old woman called Elizabeth. Imprisonment The religious tolerance which had allowed Bunyan the freedom to preach became curtailed with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The members of the Bedford Meeting were no longer able to meet in St John’s church, which they had been sharing with the Anglican congregation. That November, Bunyan was preaching at Lower Samsell, a farm near the village of Westoning, thirteen miles from Bedford, when he was warned that a warrant was out for his arrest. Deciding not to make an escape, he was arrested and brought before the local magistrate Sir Francis Wingate, at Harlington House. The Act of Uniformity, which made it compulsory for preachers to be ordained by an Anglican bishop and for the revised Book of Common Prayer to be used in church services, was still two years away, and the Act of Conventicles, which made it illegal to hold religious meetings of five or more people outside the Church of England was not passed until 1664. Bunyan was arrested under the Conventicle Act of 1593, which made it an offence to attend a religious gathering other than at the parish church with more than five people outside their family. The offence was punishable by 3 months imprisonment followed by banishment or execution if the person then failed to promise not to re-offend. The Act had been little used, and Bunyan’s arrest was probably due in part to concerns that non-conformist religious meetings were being held as a cover for people plotting against the king (although this was not the case with Bunyan’s meetings). The trial of Bunyan took place in January 1661 at the quarter sessions in Bedford, before a group of magistrates under John Kelynge, who would later help to draw up the Act of Uniformity. Bunyan, who had been held in prison since his arrest, was indicted of having “devilishly and perniciousy abstained from coming to church to hear divine service” and having held “several unlawful meetings and conventicles, to the great disturbance and distraction of the good subjects of this kingdom”. He was sentenced to three months imprisonment with transportation to follow if at the end of this time he didn’t agree to attend the parish church and desist from preaching. As Bunyan refused to agree to give up preaching, his period of imprisonment eventually extended to 12 years and brought great hardship to his family. Elizabeth, who made strenuous attempts to obtain his release, had been pregnant when her husband was arrested and she subsequently gave birth prematurely to a still-born child. Left to bring up four step-children, one of whom was blind, she had to rely on the charity of Bunyan’s fellow members of the Bedford Meeting and other supporters and on what little her husband could earn in gaol by making shoelaces. But Bunyan remained resolute: “O I saw in this condition I was a man who was pulling down his house upon the head of his Wife and Children; yet thought I, I must do it, I must do it”. Bunyan spent his 12 years’ imprisonment in Bedford County Gaol, which stood on the corner of the High Street and Silver Street. There were however occasions when he was allowed out of prison, depending on the gaolers and the mood of the authorities at the time, and he was able to attend the Bedford Meeting and even preach. His daughter Sarah was born during his imprisonment (the other child of his second marriage, Joseph, was born after his release in 1672). In prison, Bunyan had a copy of the Bible and of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, as well as writing materials. He also had at times the company of other preachers who had been imprisoned. It was in Bedford Gaol that he wrote Grace Abounding and started work on The Pilgrim’s Progress, as well as penning several tracts that may have brought him a little money. In 1671, while still in prison, he was chosen as pastor of the Bedford Meeting. By that time there was a mood of increasing religious toleration in the country and in March 1672 the king issued a declaration of indulgence which suspended penal laws against nonconformists. Thousands of nonconformists were released from prison, amongst them Bunyan and five of his fellow inmates of Bedford Gaol. Bunyan was freed in May 1672 and immediately obtained a licence to preach under the declaration of indulgence. Later life Following his release from gaol in 1672 Bunyan probably did not return to his former occupation of tinker. Instead he devoted his time to writing and preaching. He continued as pastor of the Bedford Meeting and travelled over Bedfordshire and adjoining counties on horseback to preach, becoming known affectionately as “Bishop Bunyan”. His preaching also took him to London, where Lord Mayor Sir John Shorter became a friend and presented him with a silver-mounted walking stick. The Pilgrim’s Progress was published in 1678 by Nathaniel Ponder and immediately became popular, though probably making more money for its publisher than for its author. Two events marred Bunyan’s life during the later 1670s. Firstly he became embroiled in a scandal concerning a young woman called Agnes Beaumont. When going to preach in Gamlingay in 1674 he allowed Beaumont, a member of the Bedford Meeting, to ride pillion on his horse, much to the anger of her father, who then died suddenly. His daughter was initially suspected of poisoning him, though the coroner found he had died of natural causes. And then in 1676-7 he underwent a second term of imprisonment, probably for refusing to attend the parish church. In 1688, on his way to London, Bunyan made a detour to Reading, Berkshire, to try and resolve a quarrel between a father and son. Continuing to London to the house of his friend, grocer John Strudwick of Snow Hill in the City of London, he was caught in a storm and fell ill with a fever. He died in Strudwick’s house on the morning of 31 August 1688 and was buried in the tomb belonging to Strudwick in Bunhill Fields nonconformist burial ground in London. Bunyan’s estate at his death was worth £42 19s 0d. His widow Elizabeth died in 1691. Works * Between 1656 when he published his first work, Some Gospel Truths Opened (a tract against the Quakers), and his death in 1688, Bunyan published 42 titles. A further two works, including his Last Sermon, were published the following year by George Larkin. In 1692 Southwark comb-maker Charles Doe, who was a friend of Bunyan’s later years, brought out, with the collaboration of Bunyan’s widow, a collection of the author’s works, including 12 previously unpublished titles, mostly sermons. Six years later Doe published The Heavenly Footman and finally in 1765 Relation of My Imprisonment was published, giving a total of 58 published titles. * It is the allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress, written during Bunyan’s twelve-year imprisonment although not published until 1678 six years after his release, that made Bunyan’s name as an author with its immediate success. It remains the book for which Bunyan is best remembered. The images Bunyan uses in The Pilgrim’s Progress are reflections of images from his own world; the strait gate is a version of the wicket gate at Elstow Abbey church, the Slough of Despond is a reflection of Squitch Fen, a wet and mossy area near his cottage in Harrowden, the Delectable Mountains are an image of the Chiltern Hills surrounding Bedfordshire. Even his characters, like the Evangelist as influenced by John Gifford, are reflections of real people. Further allegorical works were to follow: The Life and Death of Mr. Badman (1680), Pilgrim’s Progress Part II, and The Holy War (1682). Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, a spiritual autobiography was published in 1666, when he was still in jail. Adaptations * In March, 2015 Director Darren Wilson announced a Kickstarter campaign to produce a full-length feature film based on The Pilgrims Progress called Heaven Quest: A Pilgrim’s Progress Movie. Memorials * In 1862 a recumbent statue was created to adorn Bunyan’s grave, and restored in 1922. * In 1874, a bronze statue of John Bunyan, sculpted by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm, was erected in Bedford. This stands at the south-western corner of St Peter’s Green, facing down Bedford’s High Street. The site was chosen by Boehm for its significance as a crossroads. Bunyan is depicted expounding the Bible, to an invisible congregation, with a broken fetter representing his imprisonment by his left foot. There are three scenes from “The Pilgrim’s Progress” on the stone plinth: Christian at the wicket gate; his fight with Apollyon; and losing his burden at the foot of the cross of Jesus. The statue was unveiled by Lady Augusta Stanley, wife of the Dean of Westminster, on Wednesday 10 June 1874. In 1876 the Duke of Bedford gave bronze doors by Frederick Thrupp depicting scenes from The Pilgrim’s Progress to the Bunyan Meeting (the former Bedford Meeting which had been renamed in Bunyan’s honour). * There is another statue of him in Kingsway, London, and there are memorial windows in Westminster Abbey, Southwark Cathedral and various churches, including Elstow Abbey (the parish church of Elstow) and the Bunyan Meeting Free Church in Bedford. * Bunyan is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 30 August, and on the liturgical calendar of the United States Episcopal Church on 29 August. Some other churches of the Anglican Communion, such as the Anglican Church of Australia, honour him on the day of his death (31 August). Legacy * Bunyan is best remembered for The Pilgrim’s Progress, a book which gained immediate popularity. By 1692, four year’s after the author’s death, publisher Charles Doe estimated that 100,000 copies had been printed in England, as well as editions “in France, Holland, New England and Welch”. By 1938, 250 years after Bunyan’s death, more than 1,300 editions of the book had been printed. * During the 18th century Bunyan’s unpolished style fell out of favour, but his popularity returned with Romanticism, poet Robert Southey writing an appreciative biography in 1830. Bunyan’s reputation was further enhanced by the evangelical revival and he became a favourite author of the Victorians. The tercentenary of Bunyan’s birth, celebrated in 1928, elicited praise from his former adversary, the Church of England. Although popular interest in Bunyan waned during the second half of the twentieth century, academic interest in the writer has increased and Oxford University Press brought out a new edition of his works, beginning in 1976. Authors who have been influenced by Bunyan include Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Louisa May Alcott and George Bernard Shaw. * Bunyan’s work, in particular The Pilgrim’s Progress, has reached a wider audience through stage productions, film, TV, and radio. An opera by Ralph Vaughan Williams based on The Pilgrim’s Progress was first performed at the Royal Opera House in 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain and revived in 2012 by the English National Opera. * John Bunyan had six children, five of whom are known to have married, of which four had children. Moot Hall Museum (in Elstow) has a record of John’s descendants, down to the nineteenth century but as of September 2013, no verifiable trace of later descendants has been found. Selected bibliography * * Among Bunyan’s many works: References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Bunyan

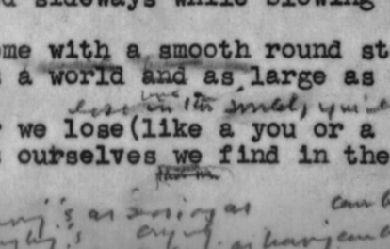

Julia Ann Moore, the “Sweet Singer of Michigan”, born Julia Ann Davis in Plainfield Township, Kent County, Michigan (December 1, 1847–June 5, 1920), was an American poet, or more precisely, poetaster. Like Scotland’s William McGonagall, she is famed chiefly for writing notoriously bad poetry. Biography Young Julia grew up on her family’s Michigan farm, the eldest of four children. When she was ten, her mother became ill, and Julia assumed many of her mother’s responsibilities. Her formal education was thereby limited. In her mid-teens, she started writing poetry and songs, mostly in response to the death of children she knew, but any newspaper account of disaster could inspire her. At age 17, she married Frederick Franklin Moore, a farmer. Julia ran a small store and, over the years, bore ten children, of whom six survived to adulthood. She continued to write poetry and songs. Moore’s first book of verse, The Sentimental Song Book was published in 1876 by C. M. Loomis of Grand Rapids, and quickly went into a second printing. A copy ended up in the hands of James F. Ryder, a Cleveland publisher, who republished it under the title The Sweet Singer of Michigan Salutes the Public. Ryder sent out numerous review copies to newspapers across the country, with a cover letter filled with low key mock praise. And so Moore received national attention. Following Ryder’s lead, contemporary reviews were amusedly negative. The Rochester Democrat wrote of Sweet Singer, that Shakespeare, could he read it, would be glad that he was dead …. If Julia A. Moore would kindly deign to shed some of her poetry on our humble grave, we should be but too glad to go out and shoot ourselves tomorrow. The Hartford Daily Times said that to meet such steady and unremitting demands on the lachrymal ducts one must be provided, as Sam Weller suspected Job Trotter was, ‘with a main, as is allus let on.’… The collection became a curious best-seller, though it is unclear whether this was due to public amusement with Moore’s poetry or genuine appreciation of the admittedly “sentimental” character of her poems. It was, more or less, the last gasp of that school of obituary poetry that had been broadly popular in the U. S. throughout the mid-19th century. Moore gave a reading and singing performance, with orchestral accompaniment, in 1877 at a Grand Rapids opera house. She managed to interpret jeering as criticism of the orchestra. Moore’s second collection, A Few Choice Words to the Public appeared in 1878, but found few buyers. Moore gave a second public performance in late 1878 at the same opera house. By then she had figured out that the praise directed to her was false and the jeering sincere. She began by admitting her poetry was “partly full of mistakes” and that “literary is a work very hard to do”. After the poetry and the laughter and jeering in response was over, Moore ended the show by telling the audience: You have come here and paid twenty-five cents to see a fool; I receive seventy-five dollars, and see a whole houseful of fools. Afterwards, her husband forbade her to publish any more poetry. Three more poems were eventually published, and she would write poems for friends. In 1880, she also published, in newspaper serialization, a short story “Lost and Found”, a strongly moralistic story about a drunkard, and a novella “Sunshine and Shadow”, a peculiar romance set in the American Revolution. The ending of “Sunshine and Shadow” was perhaps intended to be self-referential: the farmer facing foreclosure is gratefully rescued by his wife’s publishing her secret cache of fiction. According to some reports, though, her husband was not grateful, but embarrassed. Shamed or not, he moved the family 100 miles north to Manton in 1882. Moore’s notoriety was known in Manton, but the locals respected her, and did not cooperate with the occasional reporter trying to revisit the past. They were a successful business couple, he with an orchard and sawmill, she with a store. Her husband died in 1914. The next year, Julia republished “Sunshine and Shadow” in pamphlet form. She spent much of her widowhood “melancholy”, sitting on her porch. She died quietly in 1920. The news of her death was widely reported, sometimes with a light touch. On her poetry Some comparison to William McGonagall is worth making. Unlike McGonagall, Moore commanded a fairly wide variety of meters and forms, albeit like Emily Dickinson the majority of her verse is in the ballad meter. Like McGonagall, she held a maidenly bluestocking’s allegiance to the Temperance movement, and frequently indited odes to the joys of sobriety. Most importantly, like McGonagall, she was drawn to themes of accident, disaster, and sudden death; as has been said of A. E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad, in her pages you can count the dead and wounded. Edgar Wilson Nye called her “worse than a Gatling gun”. Here, she is inspired by the Great Chicago Fire: The great Chicago Fire, friends, Will never be forgot; In the history of Chicago It will remain a darken spot. It was a dreadful horrid sight To see that City in flames; But no human aid could save it, For all skill was tried in vain. Her less morbid side is on display when she hymns Temperance Reform Clubs: Many a man joined the club That never drank a drachm, Those noble men were kind and brave They care not for the slang— The slang they meet on every side: “You’re a reform drunkard, too; You’ve joined the red ribbon brigade, Among the drunkard crew.” Despite her acknowledgment that “Literary is a work very difficult to do,” she did not approve of the life of Byron: The character of “Lord Byron” Was of a low degree, Caused by his reckless conduct, And bad company. He sprung from an ancient house, Noble, but poor, indeed. His career on earth, was marred By his own misdeeds. Influence Mark Twain was a self-described fan of Moore (though not for the reasons Moore would have liked). Twain alluded to her work in Following the Equator, and it is widely assumed that Moore served as a literary model for the character of Emmeline Grangerford in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Grangerford’s funereal ode to Stephen Dowling Botts: O no. Then list with tearful eye, Whilst I his fate do tell. His soul did from this cold world fly By falling down a well. They got him out and emptied him; Alas it was too late; His spirit was gone for to sport aloft In the realms of the good and great. (Twain) is not far removed from Moore’s poems on subjects like Little Libbie: One more little spirit to Heaven has flown, To dwell in that mansion above, Where dear little angels, together roam, In God’s everlasting love. (Moore) Moore was also the inspiration for comic poet Ogden Nash, as he acknowledged in his first book, and whose daughter reported that her work convinced Nash to become a “great bad poet” instead of a “bad good poet”. The Oxford Companion to American Literature describes Nash as using Moore’s hyperdithyrambic meters, pseudo-poetic inversions, gangling asymmetrical lines, extremely pat or elaborately inexact rimes, parenthetical dissertations, and unexpected puns. Selections of Moore appeared in D. B. Wyndham-Lewis and Charles Lee’s famous Stuffed Owl anthology, and in other collections of bad poetry. Most of her poetry was reprinted in a 1928 edition, which can be found online. Her complete poetry and prose, with biography, notes, and references, can be found in the Riedlinger edited collection Mortal Refrains. Most poetry collections reprint the latest, “best”, versions of their contents. Riedlinger has adopted the opposite philosophy. Moore has been grouped into the Western Michigan School of Bad Versemakers. Her local contemporaries—including Dr. William Fuller, S.H. Ewell, J.B. Smiley, and Fred Yapple—do not appear to have had relationships with each other, but their proximity and similar penchant for exceptionally laughable verse have led to their posthumous grouping together.

David Whyte (born 2 November 1955) is an English poet. He is quoted as saying that all of his poetry and philosophy is based on "the conversational nature of reality". Life and Work Whyte's mother was from Waterford, Ireland, and his father was a Yorkshireman. He attributes his poetic interest to both the songs and poetry of his mother's Irish heritage and to the landscape of West Yorkshire. He grew up in West Yorkshire and has commented that he had "a Wordsworthian childhood", in the fields, woods and on the moors. Whyte has a degree in Marine zoology from Bangor University. During his twenties Whyte worked as a naturalist and lived in the Galapagos Islands, where he experienced a near drowning on the southern shore of Hood Island. He led anthropological and natural history expeditions in the Andes the Amazon and the Himalayas. Whyte moved to the US in 1981 and began a career as a poet and speaker in 1986. From 1987 he began taking his poetry and philosophy to larger audiences including consulting and lecturing on organisational leadership models in the US and UK exploring the role of creativity in business. He has worked with companies such as Boeing, AT&T, NASA, Toyota, The Royal Air Force and the Arthur Andersen accountancy group. Work and vocation and "Conversational Leadership" is the subject of several of Whyte's prose books, including Crossing the Unknown Sea: Work as Pilgrimage of Identity, The Three Marriages: Reimagining Work, Self and Relationship and The Heart Aroused: Poetry and the Preservation of The Soul in Corporate America (top of business best seller list). Whyte has written seven volumes of poetry and four books of prose. Pilgrim is based on the human need to travel, "From here to there". The House of Belonging looks at the same human need for home. He describes his collection Everything Is Waiting For You (2003) as arising from the grief at the loss of his mother. His latest book is Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words, an attempt to "rehabilitate" many everyday words we often use only in pejorative or unimaginative ways. He has also written for newspapers including The Huffington Post and The Observer. He leads group poetry and walking journeys regularly in Ireland, England and Italy. He has an honorary degree from Neumann College, Pennsylvania, and is Associate Fellow of both Templeton College, Oxford, and the Saïd Business School, Oxford. Whyte runs the Many Rivers organisation and Invitas: The Institute for conversational leadership, which he founded in 2014. He has lived in Seattle and on Whidbey Island and currently lives in Langley, in the US Pacific North West and holds dual US-British citizenship. He has one daughter, Charlotte, from his second marriage to Dr. Leslie Cotter, from whom he divorced in November 2014, and a son, Brendan from his first marriage to Autumn Preble. Whyte has practised Zen and was a regular rock climber. He was a close friend of the Irish poet John O'Donohue. Poetry Collections * Pilgrim (2012) * River Flow: New & Selected Poems Revised Edition (Many Rivers Press 2012) * River Flow: New & Selected Poems 1984–2007 (Many Rivers Press 2007) * Everything is Waiting for You (Many Rivers Press 2003) * The House of Belonging (Many Rivers Press 1996) * Fire in the Earth (Many Rivers Press 1992) * Where Many Rivers Meet (Many Rivers Press 1990) * Songs for Coming Home (Many Rivers Press 1984) Prose * The Three Marriages: Reimagining Work, Self & Relationship (Riverhead 2009) * Crossing the Unknown Sea: Work as A Pilgrimage of Identity (Riverhead 2001) * The Heart Aroused: Poetry & the Preservation of the Soul in Corporate America (Doubleday/Currency 1994) * Consolations: The Solace Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words" (Many Rivers Press 2015) References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Whyte_(poet)

Francisco Pino (Valladolid, 18 de enero de 1910 - íd., 2002), poeta español. Perteneciente a una importante familia burguesa, nunca se interesó por los intereses económicos familiares y, por el contrario, apoyado por su madre, mujer muy culta y buena lectora, se inclinó por el camino intelectual. Tras pasar por el Colegio de Lourdes de Valladolid, comenzó en 1927 la carrera de Derecho en la Universidad de Valladolid. en 1927 conoce a Jorge Guillén, cuyo Cántico le influirá en su primera poesía junto la vanguardia creacionista. Al año siguiente funda en Valladolid, junto a José María Luelmo, Arroyo y Juan R. Ribó, la revista poética Meseta. Viaja a Francia en 1930 y allí cursa estudios de Filología Francesa y se involucra en el movimiento surrealista, después funda DDOOSS (1931), año en que se licencia en Derecho. En 1933 marchó a estudiar inglés y Ciencias Económicas en la Universidad de Londres; en Inglaterra revive su interés por el Catolicismo y funda la revista A la nueva ventura (1934); regresa a España en 1935 para matricularse en la Universidad Central de Madrid. Al finalizar la Guerra Civil, durante la cual sufrió traumáticas experiencias, vivió una especie de activo exilio interior en su casa modernista en el Pinar de Antequera (Valladolid), en compañía de su esposa, entregado a elaborar su obra poética, fiel a la Vanguardia histórica y poco publicitada, de la que dan fe unos setenta títulos que contienen su poesía experimental, visual y religiosa. De esta actividad da fe que fundó y dirigió no menos de nueve revistas de poesía: Meseta (1928), Ddooss (1931), A la nueva ventura (1934), Cancionero (1941), Mejana (1965), Carpetas amarillas (1971), Carpetas blancas (1975), Carpetas grises (1976), Carpetas verdes (1978). En 1989 recibió el Premio de las Letras de Castilla y León y la Medalla de Oro del Círculo de Bellas de Madrid. La Academia Castellano Leonesa de Poesía le entregó en el año 2000 un premio por el conjunto de su obra y en abril de 2002, pocos meses antes de su muerte, publicó su último libro Claro decir, Canto a la vejez. En los tres volúmenes de Distinto y junto. Poesía completa (1990), cuyo título alude a un verso de Fray Luis, se halla la edición de su poesía hasta 1990, en documentada edición a cargo de Antonio Piedra. En 1989 recibió el Premio Castilla y León de las Letras; en 1993 el Premio Provincia de Valladolid por su trayectoria literaria; en 1999 fue homenajeado en las Primeras Jornadas de Poesía Iberoamericana y al año siguiente fue nombrado Hijo Predilecto de Valladolid, la Academia Castellano Leonesa de Poesía le entregó un premio por el conjunto de su obra y obtuvo el Premio El Norte de Castilla por su trayectoria literaria. Escritura La poesía de Pino se mantuvo fiel a las Vanguardias: poesía gráfica que incluye poemas fotográficos y tipográficos, cartelas y mosaicos. Francisco Pino inició su vida literaria como fundador y colaborador de las revistas Meseta (1928-29), DDOOSS (1931) y A la nueva ventura (1934), donde realizó una intensa labor surrealista. Jorge Guillén, Federico García Lorca y Rafael Alberti fueron algunos de los colaboradores de estas revistas. Durante la guerra civil comienza una serie de poemas amorosos que publica en 1942 bajo el título de Espesa rama. En 1957 publica Vuela pluma, bajo la influencia juanramoniana, en 1966 reúne su poesía religiosa en Cinco preludios. En 1969 aparece el último libro de esta etapa, Textos económicos. Continúa en 1970 con uno de los libros claves de la poesía experimental española, Solar, al que le siguen Poema (1972), Hombre, Canción (1973), Octaedro mortal o reloj de arena (1973), formando lo que el autor denomina Agujeros para la poesía. El crítico Antonio Piedra reunió en 1994 su obra vanguardista en la colección Siyno sino. El poeta y profesor de literatura Mario Hernández define a Francisco Pino como «poeta que ha asumido con voluntaria decisión las contradicciones históricas que marcan a los miembros de la llamada generación del 36, haciéndose él mismo depositario conflictivo de unas herencias y de su repudio o superación por una vía irónica o experimental». Obras Lírica * Espesa rama, M., Gráficas Sánchez, 1942. * XXXV canciones del sol, Valladolid, Gesper, 1952. * Versos religiosos, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1954. * El caballero y la peonía, Valladolid, Miñón, 1955. * El pájaro y los muros, Valladolid, Miñón, 1955. * Vida de San Pedro Regalado, sueño, Valladolid, Meseta, 1956. * Vuela pluma, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1957. * Las raíces y el aire, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1958. * Pet, poema, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1959. * Este sitio, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1961. * San José, preludio, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1961. * Alegría, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1964. * Camino de la cruz, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1965. * Más cerca, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1965. * Cinco preludios, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1966. * Concierto de la virgen joven, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1967. * Vía Crucis, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1967. * Concierto del niño verdadero, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1968. * Desamparo, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1968. * Concierto de los Reyes Magos, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1969. * Las ausencias, Málaga, Librería Anticuaria El Guadalhorce, 1969. * Solar, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1969. * Textos económicos, Valladolid, Librería Relieve, 1969. * 15 poemas fotografiados (diapositivas), Valladolid, Impr. Ambrosio Rodríguez, 1971. * Concierto de la virgen vieja, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1971. * Poema, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1972. * Revela velado, Valladolid, Impr. Ambrosio Rodríguez, 1972. * Cinco conciertos de Navidad, Valladolid, Sever-Cuesta, 1973. * Hombre, canción, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1973. * Octaedro mortal o reloj de arena, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1973. * Bloques, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1974. * La salida, Carboneras de Guadazaón, El toro de barro, 1974. * Ocho infinito (8 postales), Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1974. * Terrón, cántico, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1974. * Oes, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1975. * El júbilo: la última sílaba, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1976. *Realidad, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1976. * Ventana oda, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1976. * Algo a Jorge Guillén, Valladolid, Impr. A. Rodríguez, 1977. * Antisalmos, M., Peralta, 1978. * Nada más que mirar, M., Entregas de la Ventura, 1980. * Desnudos, Valladolid, Gráficas Andrés Martín, 1981. * Méquina dalicada, M., Hiperión, 1981. * Siete silvas, Valladolid, Balneario escrito, 1981. * Vuela pluma, seguido de Versos para distraerme, M., Editora Nacional, 1982. * Cuaderno salvaje, M., Hiperión, 1983. * En no importa que idioma, Salamanca, Junta de Castilla y León, 1986. * Así que, M., Hiperión, 1987. * Hay más, M., Hiperión, 1989. * Distinto y junto, Valladolid, Consejería de Cultura, 1990 (Poesía completa; 3 vols.; edición; prólogo y notas de Antonio Piedra). * Apremio de una sirena, Velliza, El gato gris; Ediciones de poesía, 1992. * Y por qué, M., Hiperión, 1992. * Syino Sino. Poesía cierta mente ciertamente, Valladolid, Fundación Jorge Guillén, 1995 (3 vols. Poesías completas. Introduc. de Antonio Piedra). * Tejas: lugar de Dios, Poema, Azul, Valladolid, 2000. * Claro decir, B., Lumen, 2002. * El pájaro enjaulado. Poema en treinta y dos cantos y una poetura del lorito en su jaula, Valladolid, Azul, 2002. Otros * Vía crucis (1965). Prosa religiosa. * Invisibilidad de Castilla (1969). Conferencia. * Hacia la poesía (1972). Conferencia. * Discurso leído en el Ateneo con ocasión del homenaje a la revista "Meseta" en el cincuentenario de su nacimiento (1978). Discurso. * "Castilla y los cinco sentidos", en PÉREZ, Federico, Castilla, libro del milenario de la lengua (1979). Artículo. * "Prólogo" a ALEJO, Justo, El aroma del viento (1980). Prólogo."Hacia la poesía", revista Llanuras, núm. 3 (1983). Artículo. * Discurso leído en el Ateneo con ocasión de su nombramiento como socio de honor del mismo (1984). Discurso. * Pregón de la Semana Santa de 1957, en AAVV, Pregones de Semana Santa (1948-1983) (1984). Discurso. * Sobre la manifestación y el último lenguaje en poesía (1985). * En no importa qué idioma (1986). * "El premio en su fiel", Culturas (suplemento de Diario 16), núm. 255, 5 de mayo de 1990. Artículo. * "Sobre San Juan de la Cruz", Artes y Letras (suplemento de El Norte de Castilla), 14 de diciembre de 1991. Artículo. * "Nebrija y los Reyes Católicos a través de mis versos", Artes y Letras (suplemento de El Norte de Castilla), núm. 189, 1992. Artículo. * "Última carta a Jorge Guillén", Culturas (suplemento de Diario 16), núm. 379, 16 de enero de 1993. Artículo. * "Tres detalles quedan", Revista de Occidente, núm. 144 (mayo de 1993). * "Traducción infiel de 'Cántico de las columnas', de Paul Valéry", revista Pavesas. Hojas de poesía, núm 10 (1997). Traducción. * Traducción infiel de "El cuervo" de Edgar Allan Poe (1997). Traducción. * Discurso leido en el Ayuntamiento de Valladolid, en conmemoración del centanario de la imprenta Ambrosio Rodríguez. (1998) * Presentación del libro "desde el escaparate de Ambrosio Rodríguez 1898-1998" * Del sentimiento de academia en los poetas (1998). Discurso. Referencias Wikipedia-http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Pino Poética del hueco por Jorge Fernández Gonzalo Francisco Pino es uno de esos poetas poco leídos, raros, de nuestra lírica, que esconden, sin embargo, más de una joya bajo el silencio de su trayectoria poética. Pino, como Jaime Gil de Biedma, soñó con hacerse literatura, y toda su obra supondrá el intento por desaparecer a través de la desviación que propone todo lenguaje, mediante la pátina de la palabra poética, bajo la fragmentación y hollado de la subjetividad. Un poeta anónimo Pino no es sólo un poeta desconocido, sino que casi roza lo anónimo. “Mi deseo –dirá el autor– sería ser un poeta biológicamente y hasta antropológicamente desconocido. Que mi verso, mi cuerpo humano y mi vestido, toda mi apariencia fuese anónima”. Frente al maremagno de certámenes, galas y presentaciones de libros del panorama literario, Pino propone un sujeto poético mallarmeano, esto es, desapareciendo gracias a la escritura, destruyéndose al mismo tiempo que se escribe el texto. Autores como Foucault, Barthes o Blanchot han hablado de esa muerte del autor. Pino, en esta misma línea, llegará a decir en un poema: “¿Habrá algo más hermoso que quedar sin huellas?”. El yo poético se eslabona como hueco, como carencia que toma forma en las estriaciones de la palabra poética sobre el papel o en los juegos caligramáticos, recortes de prensa y otras “poeturas”, como definió el poeta a sus propias perversiones literarias. Entonces, la escritura no consistirá en establecer el relato de un yo, sino la fragmentación del sujeto moderno: “He deseado ser carne de olvido, no saber de mi existencia actual histórica”. De ahí cierta admiración por todo aquello que desaparece. “Todo lo que desaparece se me antoja vivo y hermoso”, será uno de los esclarecedores versos de Pino. Una poética del hueco Pino nos propone una poética del hueco. Al igual que Mallarmé hablaba de los grandes agujeros azules que hacen maliciosamente los pájaros, o como unas palabras de Artaud (“Existe un agujero sin marco / que la vida quiso enmascarar”), Pino habla continuamente de agujeros en su poética, formas por donde la presencia se escapa, ruptura con la subjetividad plena, con los grandes relatos que configuran el yo. El agujero es, para nuestro autor, el territorio de la palabra poética, su destino, su apuesta ontológica. Antonio Piedra, el más importante estudioso de la obra de Francisco Pino, definirá la función de las oquedades en Francisco Pino: “concretando. ¿Qué sería el agujero para Pino? Un principio activo por el que la intangibilidad poética, en los márgenes de la nada, totaliza el perfil de la materia convirtiéndose en experiencia beligerante y creadora”. Las palabras y el yo tienen en la poesía de Pino esa secreta filiación con la oquedad. Oquedad ontológica, hueco del ser, que identifica la vida con la fragmentación y la poesía con esa búsqueda de lo fragmentario, con ese reconocimiento del olvido. Quizá por ello algunos de los poemas más memorables de Pino, los Antisalmos, en donde la materia poética se adelgaza hasta casi lo imperceptible, con efectos de poesía espacial, versos entrecortados, blancos en primera línea de visión, etc., que hacen de la palabra de Pino un intento por evadirse, por borrar el lenguaje y a sí misma, y, como esa nube de sus poemas, ofrecernos la belleza de su desaparición. Referencias http://elrincondelperromugre.blogspot.com.es/2011/07/francisco-pino-antologia-poetica.html

siendo un hombre sincero que entrega su alma por completo han jugado con migo dejando mi alma sin anhelo en muchas batallas e peleado muchas cicatrices me han dejado y la experiencia ninguna me a quedado por que en el amor todo es inesperado levantando mi espada que no es mas que mi alma desesperada donde su filo es mi corazón inspirando en mi poemas desenfrenados los cuales escribo dejando en cada uno la tinta de mi corazón tal ves muchos concuerden que valientes solo son guerreros que se enfrentan a la muerte solo son seres inconscientes guerrera es mi espada que se levanta como animada desenfrenada y aturdida mi espada es mi alma yo corto con palabras y libro mis batallas solo con la voz de mi corazón soy veterano de guerras perdidas en el desamor

José Carlos Becerra (Villahermosa, Tabasco, 21 de mayo de 1936 - Brindisi, Italia, 27 de mayo de 1970) fue un poeta mexicano. Sobre un poeta, su otoño, sus islas y su niña “Espero una carta todavía no escrita donde el olvido me nombre su heredero”. —José Carlos Becerra Me parece verlo apresurado y desvelado, en los restiradores de la biblioteca de la Facultad, preparando de última hora sus trabajos en papel destraza. Con su barba de candado y su gabardina un poco arrugada; era estudiante de arquitectura en sus ratos libres, pero en la vida real, era POETA. Acababa de terminar su primer libro: “La corona de hierro”. Llegó una mañana a la imprenta que lo publicaría, con la prisa que lo caracterizaba para cambiar el título, al final se llamó: “Relación de los hechos”. ¿Su nombre?: José Carlos Becerra. Nunca lo conocí en persona, nació en Villahermosa, Tabasco en 1936. Los años y la magia de la literatura que es la verdadera máquina del tiempo, me lo presentaron una tarde y es ahora uno de los amigos que más quiero. Apreciado y admirado por todos, hubo fiesta cuando se le otorgó la beca de la Fundación Memorial Guggenheim, premio que ha cambiado las vidas de muchos autores latinoamericanos. Milagro que algunos anhelamos. Se fue a Europa, compró un Volkswagen sedán algo deteriorado, con una puerta chueca y recorrió los lugares testigos del periodo clásico de la humanidad. Era 1970 cuando en Brindisi, Italia, al tomar una curva en la carretera que lo llevaría a un transbordador rumbo a Grecia, perdió el control del auto y se desbarrancó. Murió joven, 33 años. Lejos de su familia y de su amado Tabasco. Un brevísimo aviso de un periódico mexicano, hizo a algunos amigos temer lo peor. Al confirmarse la triste noticia, después de los trámites de traslado y muchas, muchísimas lágrimas, llegó el momento de rescatar sus manuscritos para evitar al tiempo inexorable lo oportunidad de sepultar su obra. Amigos de verdad y colegas de la talla de Octavio Paz, Alí Chumacero, José Emilio Pacheco y Homero Aridjis, colaboraron en ese trabajo de amor y construcción de un volumen de 350 páginas que contiene toda su poesía: “El otoño recorre las islas”. Cabe en un bolsillo, pero contiene la obra de un poeta que vale la pena leer, releer y recordar para toda la vida. Como se dice en estos casos: de haber vivido más, si ya era prodigioso, lo que hubiera logrado. El volumen en cuestión, rescatado y estructurado por sus amigos, contiene su libro publicado en vida, antes citado, y varios otros libros de poesía; también un relato “Fotografía junto a un tulipán”. Es fácil de conseguir, en librerías, editorial Joaquín Mortiz. Pero la historia tuvo una posdata, años después, la joven escritora Silvia Molina, sorprendió a todo México con una magnífica novela autobiográfica llamada “La mañana debe seguir gris”. En ella relata un periodo de su propia vida en el que realiza un viaje a Londres para estudiar inglés; se queda a vivir en la casa de una tía. Silvia era muy joven, 24 años y se enamora perdidamente de un poeta mexicano sin fortuna pero muy prometedor por su talento, diez años mayor que ella. El idilio entre ambos va floreciendo, en el protocolario ambiente británico, bajo la complicidad de amigas y primas y la reprobación autoritaria de su tía. El poeta en cuestión era sumamente simpático, ocurrente y audaz; seductor espontáneo pero de un gran corazón cargado de esperanza. Ese poeta era José Carlos Becerra, en las semanas previas a su muerte. “La mañana debe seguir gris” es una novela breve, dinámica, muy creativa Ofrece una introducción muy original al tema con formato de diario íntimo, donde nos pone al tanto de las circunstancias y nos describe ampliamente el acontecer periodístico, hoy histórico, que rodea los hechos. En 1977 este libro ganó el premio Xavier Villaurrutia, uno de los más prestigiados de México, tras una gran polémica entre los críticos y el jurado del premio. No faltó quien dijo que la historia “demeritaba la figura del gran poeta José Carlos Becerra”. Por favor, como si un joven poeta soltero, no tuviera derecho a enamorarse. Silvia Molina es una de las autoras más jóvenes que ha ganado ese codiciado premio nacional, por cierto muy bien merecido. Aparte de que se trata de una novela que vale mucho la pena leer, nos regala un retrato vivo, nítido y más claro que un video HD, del añorado poeta, muerto a la edad de Jesús y de Ramón López Velarde. Para quienes no tuvimos la fortuna de conocerlo en persona, el relato de Silvia Molina es muy valioso, sobre todo después de terminar la lectura del maravilloso libro de José Carlos que contiene toda su obra. Así pues, en la intimidad de mi Biblioteca, siempre me aseguro de que ambos libros permanezcan juntos. Un amor de juventud que no pudo consumarse en la tierra, se guardará para siempre con sus dos nombres fundidos en la historia de la literatura mexicana. Dejo los títulos de ambos libros uno junto al otro porque, si nos damos cuenta, forman una hermosa frase: “El otoño recorre las islas, la mañana debe seguir gris” – Alfredo Jiménez G.

George Crabbe (/kræb/; 24 December 1754– 3 February 1832) was an English poet, surgeon, and clergyman. He is best known for his early use of the realistic narrative form and his descriptions of middle and working-class life and people. In the 1770s, Crabbe began his career as a doctor’s apprentice, later becoming a surgeon. In 1780, he travelled to London to make a living as a poet. After encountering serious financial difficulty and being unable to have his work published, he wrote to the statesman and author Edmund Burke for assistance. Burke was impressed enough by Crabbe’s poems to promise to help him in any way he could. The two became close friends and Burke helped Crabbe greatly both in his literary career and in building a role within the church. Burke introduced Crabbe to the literary and artistic society of London, including Sir Joshua Reynolds and Samuel Johnson, who read The Village before its publication and made some minor changes. Burke secured Crabbe the important position of Chaplain to the Duke of Rutland. Crabbe served as a clergyman in various capacities for the rest of his life, with Burke’s continued help in securing these positions. He developed friendships with many of the great literary men of his day, including Sir Walter Scott, whom he visited in Edinburgh, and William Wordsworth and some of his fellow Lake Poets, who frequently visited Crabbe as his guests. Lord Byron described him as “nature’s sternest painter, yet the best.” Crabbe’s poetry was predominantly in the form of heroic couplets, and has been described as unsentimental in its depiction of provincial life and society. The modern critic Frank Whitehead wrote that “Crabbe, in his verse tales in particular, is an important–indeed, a major–poet whose work has been and still is seriously undervalued.” Crabbe’s works include The Village (1783), Poems (1807), The Borough (1810), and his poetry collections Tales (1812) and Tales of the Hall (1819). Biography Early life Crabbe was born in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, the eldest child of George Crabbe Sr. The elder George Crabbe had been a teacher at a village school in Orford, Suffolk, and later in Norton, near Loddon, Norfolk; he later became a tax collector for salt duties, a position that his own father had held. As a young man he married an older widow named Craddock, who became the mother of his six children: George, his brothers Robert, John, and William, his sister Mary, and another sister who died as an infant. George Jr. spent his first 25 years close to his birthplace. He showed an aptitude for books and learning at an early age. He was sent to school while still very young, and developed an interest in the stories and ballads that were popular among his neighbors. His father owned a few books, and used to read passages from John Milton and from various 18th-century poets to his family. He also subscribed to a country magazine called Martin’s Philosophical Magazine, giving the “poet’s corner” section to George. The senior Crabbe had interests in the local fishing industry, and owned a fishing boat; he had contemplated raising his son George to be a seaman, but soon found that the boy was unsuited to such a career. George’s father respected his son’s interest in literature, and George was sent first to a boarding-school at Bungay near his home, and a few years later to a more important school at Stowmarket, where he gained an understanding of mathematics and Latin, and a familiarity with the Latin classics. His early reading included the works of William Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, who had a great influence on George’s future works, Abraham Cowley, Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser. He spent three years at Stowmarket before leaving school to find a physician to be apprenticed to, as medicine had been settled on as his future career. In 1768 he was apprenticed to a local doctor at Wickhambrook, near Bury St Edmunds. This doctor practiced medicine while also keeping a small farm, and George ended up doing more farm labour and errands than medical work. In 1771 he changed masters and moved to Woodbridge, where he remained until 1775. While at Woodbridge he joined a small club of young men who met at an inn for evening discussions. Through his contacts at Woodbridge he met his future wife, Sarah Elmy. Crabbe called her “Mira”, later referring to her by this name in some of his poems. During this time he began writing poetry. In 1772, a lady’s magazine offered a prize for the best poem on the subject of hope, which Crabbe won. The same magazine printed other short pieces of Crabbe’s throughout 1772. They were signed “G. C., Woodbridge,” and included some of his lyrics addressed to Mira. Other known verses written while he was at Woodbridge show that he made experiments in stanza form modeled on the works of earlier English poets, but only showed some slight imitative skill. 1775 to 1785 His first major work, a satirical poem of nearly 400 lines in Pope’s couplet form entitled Inebriety, was self-published in 1775. Crabbe later said of the poem, which received little or no attention at the time, “Pray let not this be seen... there is very little of it that I’m not heartily ashamed of.” By this time he had completed his medical training and had returned home to Aldeburgh. He had intended to go on to London to study at a hospital, but he was forced through low finances to work for some time as a local warehouseman. He eventually travelled to London in 1777 to practice medicine, returning home in financial difficulty after a year. Crabbe continued to practice as a surgeon after returning to Aldeburgh, but as his surgical skills remained deficient, he attracted only the poorest patients, and his fees were small and undependable. This hurt his chances of an early marriage, but Sarah stayed devoted to him. In late 1779 he decided to move to London and see if he could make it as a poet, or, if that failed, as a doctor. He moved to London in April 1780, where he had little success, and by the end of May he had been forced to pawn some of his possessions, including his surgical instruments. He composed a number of works but was refused publication. He wrote several letters seeking patronage, but these were also refused. In June Crabbe witnessed instances of mob violence during the Gordon Riots, and recorded them in his journal. He was able to publish a poem at this time entitled The Candidate, but it was badly received by critics. He continued to rack up debts that he had no way of paying, and his creditors pressed him. He later told Walter Scott and John Gibson Lockhart that “during many months when he was toiling in early life in London he hardly ever tasted butchermeat except on a Sunday, when he dined usually with a tradesman’s family, and thought their leg of mutton, baked in the pan, the perfection of luxury.” In early 1781 he wrote a letter to Edmund Burke asking for help, in which he included samples of his poetry. Burke was swayed by Crabbe’s letter and a subsequent meeting with him, giving him money to relieve his immediate wants, and assuring him that he would do all in his power to further Crabbe’s literary career. Among the samples that Crabbe had sent to Burke were pieces of his poems The Library and The Village. A short time after their first meeting Burke told his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds that Crabbe had “the mind and feelings of a gentleman.” Burke gave Crabbe the footing of a friend, admitting him to his family circle at Beaconsfield. There he was given an apartment, supplied with books, and made a member of the family. The time he spent with Burke and his family helped by enlarging his knowledge and ideas, and introducing him to many new and valuable friends including Charles James Fox and Samuel Johnson. He completed his unfinished poems and revised others with the help of Burke’s criticism. Burke helped him have his poem, The Library, published anonymously in June 1781, by a publisher that had previously refused some of his work. The Library was greeted with modest praise from critics, and slight public appreciation. Through their friendship, Burke discovered that Crabbe was more suited to be a clergyman than a surgeon. Crabbe had a good knowledge of Latin and an evident natural piety, and was well read in the scriptures. He was ordained to the curacy of his native town on 21 December 1781 through Burke’s recommendation. He returned to live in Aldeburgh with his sister and father, his mother having died in his absence. Crabbe was surprised to find that he was poorly treated by his fellow townsmen, who resented his rise in social class. With Burke’s help, Crabbe was able to leave Aldeburgh to become chaplain to the Duke of Rutland at Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire. This was an unusual move on Burke’s part, as this kind of preferment would usually have been given to a family member or personal friend of the Duke or through political interest. Crabbe’s experience as Chaplain at Belvoir was not altogether happy. He was treated with kindness by the Duke and Duchess, but his slightly unpolished manners and his position as a literary dependent made his relations with others in the Duke’s house difficult, especially the servants. However, the Duke and Duchess and many of their noble guests shared an interest in Crabbe’s literary talent and work. During his time there, his poem The Village was published in May 1783, achieving popularity with the public and critics. Samuel Johnson said of the poem in a letter to Reynolds “I have sent you back Mr. Crabbe’s poem, which I read with great delight. It is original, vigorous, and elegant.” Johnson’s friend and biographer James Boswell also praised The Village. It was said at the time of publication that Johnson had made extensive changes to the poem, but Boswell responded by saying that “the aid given by Johnson to the poem, as to The Traveller and Deserted Village of Goldsmith, were so small as by no means to impair the distinguished merit of the author.” Crabbe was able to keep up his friendships with Burke, Reynolds, and others during the Duke’s occasional visits to London. He visited the theatre, and was impressed with the actresses Sarah Siddons and Dorothea Jordan. Around this time it was decided that, as Chaplain to a noble family, Crabbe was in need of a college degree, and his name was entered on the boards of Trinity College, Cambridge, through the influence of Bishop Watson of Llandaff, so that Crabbe could obtain a degree without residence. This was in 1783, but almost immediately afterwards he received an LL.B. degree from the Archbishop of Canterbury. This degree allowed Crabbe to be given two small livings in Dorsetshire, Frome St Quintin and Evershot. This promotion does not seem to have interfered with Crabbe’s residence at Belvoir or in London; it is likely that curates were placed in these situations. On the strength of these preferments and a promise of future assistance from the Duke, Crabbe and Sarah Elmy were married in December 1783, in the parish church of Beccles, where Miss Elmy’s mother lived, and a few weeks later went to live together at Belvoir Castle. In 1784 the Duke of Rutland became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. It was decided that Crabbe was not to be on the Duke’s staff in Ireland, though the two men parted as close friends. The young couple stayed on at Belvoir for nearly another eighteen months before Crabbe accepted a vacant curacy in the neighbourhood, that of Stathern in Leicestershire, where Crabbe and his wife moved in 1785. A child had been born to them at Belvoir, dying only hours after birth. During the following four years at Stathern they had three other children; two sons, George and John, in 1785 and 1787, and a daughter in 1789, who died in infancy. Crabbe later told his children that his four years at Stathern were the happiest of his life. 1785 to 1810 In October 1787 the Duke of Rutland died at the Vice-Regal Lodge in Dublin, after a short illness, at the early age of 35. Crabbe assisted at the funeral at Belvoir. The Duchess, anxious to have their former chaplain close by, was able to get Crabbe the two livings of Muston, Leicestershire, and Allington, Lincolnshire, in exchange for his old livings. Crabbe brought his family to Muston in February 1789. His connection with the two livings lasted for over 25 years, but during 13 of these years he was a non-resident. He stayed three years at Muston. Another son, Edmund, was born in 1790. In 1792, through the death of one of Sarah’s relations and soon after of her older sister, the Crabbe family came into possession of an estate in Parham, which removed all of their financial worries. Crabbe soon moved his family to this estate. Their son William was born the same year. Crabbe’s life at Parham was not happy. The former owner of the estate had been very popular for his hospitality, while Crabbe’s lifestyle was much more quiet and private. His solace here was the company of his friend Dudley Long North and his fellow Whigs who lived nearby. Crabbe soon sent his two sons George and John to school in Aldeburgh. After four years at Parham, the Crabbes moved to a home in Great Glemham, Suffolk, placed at his disposal by Dudley North. The family remained here for four or five years. In 1796 their third son, Edmund died at the age of six. This was a heavy blow to Sarah who began suffering from a nervous disorder from which she never recovered. Crabbe, a devoted husband, tended her with exemplary care until her death in 1813. Robert Southey, writing about Crabbe to his friend, Neville White, in 1808, said “It was not long before his wife became deranged, and when all this was told me by one who knew him well, five years ago, he was still almost confined in his own house, anxiously waiting upon this wife in her long and hopeless malady. A sad history! It is no wonder that he gives so melancholy a picture of human life.” During his time at Glemham, Crabbe composed several novels, none of which were published. After Glemham, Crabbe moved to the village of Rendham in Suffolk, where he stayed until 1805. His poem The Parish Register was all but completed while at Rendham, and The Borough was also begun. 1805 was the last year of Crabbe’s stay in Suffolk, and it was made memorable in literature by the appearance of the Lay of the Last Minstrel by Walter Scott. Crabbe first saw it in a bookseller’s shop in Ipswich, read it nearly through while standing at the counter, and pronounced that a new and great poet had appeared. In October 1805, Crabbe returned with his wife and two sons to the parsonage at Muston. He had been absent for nearly 13 years, of which four had been spent at Parham, five at Great Glemham, and four at Rendham. In September 1807, Crabbe published a new volume of poems. Included in this volume were The Library, The Newspaper, and The Village; the principal new poem was The Parish Register, to which were added Sir Eustace Grey and The Hall of Justice. The volume was dedicated to Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, nephew and sometime ward of Charles James Fox. An interval of 22 years had passed since Crabbe’s last appearance as an author, and he explained in the preface to this volume the reasons for this lapse as being his higher calling as a clergyman and his slow progress in poetical ability. This volume led to Crabbe’s general acceptance as an important poet. Four editions were issued during the following year and a half, the fourth appearing in March 1809. The reviews were unanimous in approval, headed by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review. In 1809 Crabbe sent a copy of his poems in their fourth edition to Walter Scott, who acknowledged them in a friendly reply. Scott told Crabbe “how for more than twenty years he had desired the pleasure of a personal introduction to him, and how, as a lad of eighteen, he had met with selections from The Village and The Library in The Annual Register.” This exchange of letters led to a friendship that lasted for the rest of their lives, both authors dying in 1832. Crabbe’s favorite among Scott’s “Waverley” novels was The Heart of Midlothian. The success of The Parish Register in 1807 encouraged Crabbe to proceed with a far longer poem, which he had been working on for several years. The Borough was begun at Rendham in Suffolk in 1801, continued at Muston after his return in 1805, and finally completed during a long visit to Aldeburgh in the autumn of 1809. It was published in 1810. In spite of its defects, The Borough was an outright success. The poem appeared in February 1810, and went through six editions in the next six years. When he visited London a few years later and was received with general welcome in the literary world, he was very surprised. “In my own village,” he told James Smith, “they think nothing of me.” The three years following the publication of The Borough were especially lonely for him. He did have his two sons, George and John, with him; they had both passed through Cambridge, one at Trinity and the other at Caius, and were now clergymen themselves, each holding a curacy in the neighbourhood, enabling them to live under the parental roof, but Mrs. Crabbe’s health was now very poor, and Crabbe had no daughter or female relative at home to help him with her care. Later life Crabbe’s next volume of poetry, Tales was published in the summer of 1812. It received a warm welcome from the poet’s admirers, and was favorably reviewed by Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review and is considered to be his masterpiece. In the summer of 1813, Mrs. Crabbe felt well enough to want to see London again, and the father and mother and two sons spent nearly three months in rooms in a hotel. Crabbe was able to visit Dudley North and some of his other old friends, and to visit and help the poor and distressed, remembering his own want and misery in the great city thirty years earlier. The family returned to Muston in September, and Mrs. Crabbe died at the end of October at the age of 63. Within days of his wife’s death Crabbe fell seriously ill, and was in danger of dying. He rallied, however, and returned to the duties of his parish. In 1814, he became Rector of Trowbridge in Wiltshire, a position given to him by the new Duke of Rutland. He remained at Trowbridge for the rest of his life. His two sons followed him, as soon as their existing engagements allowed them to leave Leicestershire. The younger, John, who married in 1816, became his father’s curate, and the elder, who married a year later, became curate at Pucklechurch, also nearby. Crabbe’s reputation as a poet continued to grow in these years. His growing reputation soon made him a welcome guest in many houses to which his position as vicar of Trowbridge might not have admitted him. Nearby was the poet William Lisle Bowles, who introduced Crabbe to the noble family at Bowood House, home of the Marquess of Lansdowne, who was always ready to welcome those distinguished in literature and the arts. It was at Bowood House that Crabbe first met the poet Samuel Rogers, who became a close friend and had an influence on Crabbe’s poetry. In 1817, on the recommendation of Rogers, Crabbe stayed in London from the middle of June to the end of July in order to enjoy the literary society of the capital. While there he met Thomas Campbell, and through him and Rogers was introduced to his future publisher John Murray. In June 1819, Crabbe published his collection Tales of the Hall. The last 13 years of Crabbe’s life were spent at Trowbridge, varied by occasional visits among his friends at Bath and the surrounding neighbourhood, and by yearly visits to his friend Samuel Hoare Jr in Hampstead. From here it was easy to visit his literary friends in London, while William Wordsworth, Southey, and others occasionally stayed with the family. Around 1820 Crabbe began suffering from frequent severe attacks of neuralgia, and this illness, together with his age, made him less and less able to travel to London. In the spring of 1822, Crabbe met Walter Scott for the first time in London, and promised to visit him in Scotland in the fall. He kept this promise during George IV’s visit to Edinburgh, in the course of which the King met Scott and the poet was given a wine glass from which the King had drunk. Scott returned from the meeting with the King to find Crabbe at his home. As John Gibson Lockhart related in his Life of Sir Walter Scott, Scott entered the room that had been set aside for Crabbe, wet and hurried, and embraced Crabbe with brotherly affection. The royal gift was forgotten—the ample skirt of the coat within which it had been packed, and which he had hitherto held cautiously in front of his person, slipped back to its more usual position—he sat down beside Crabbe, and the glass was crushed to atoms. His scream and gesture made his wife conclude that he had sat down on a pair of scissors, or the like: but very little harm had been done except the breaking of the glass. Later in 1822, Crabbe was invited to spend Christmas at Belvoir Castle, but was unable to make the trip because of the winter weather. While at home, he continued to write a large amount of poetry, leaving 21 manuscript volumes at his death. A selection from these formed the Posthumous Poems, published in 1834. Crabbe continued to visit at Hampstead throughout the 1820s, often meeting the writer Joanna Baillie and her sister Agnes. In the autumn of 1831, Crabbe visited the Hoares. He left them in November, expressing his pain and sadness at leaving in a letter, feeling that it might be the last time he saw them. He left Clifton in November, and went direct to his son George, at Pucklechurch. He was able to preach twice for his son, who congratulated him on the power of his voice, and other encouraging signs of strength. “I will venture a good sum, sir,” he said, “that you will be assisting me ten years hence.” “Ten weeks” was Crabbe’s answer, and the prediction was right almost to the day. After a short time at Pucklechurch, Crabbe returned to his home at Trowbridge. Early in January he reported continued drowsiness, which he felt was a sign of increasing weakness. Later in the month he was prostrated by a severe cold. Other complications arose, and it soon became apparent that he would not live much longer. He died on 3 February 1832, with his two sons and his faithful nurse by his side. Poetry Crabbe’s poetry was predominantly in the form of heroic couplets, and has been described as unsentimental in its depiction of provincial life and society. John Wilson wrote that “Crabbe is confessedly the most original and vivid painter of the vast varieties of common life that England has ever produced;” and that “In all the poetry of this extraordinary man, we see a constant display of the passions as they are excited and exacerbated by the customs, laws, and institutions of society.” The Cambridge History of English Literature saw Crabbe’s importance to be more in his influence than in his works themselves: “He gave the poetry of nature new worlds to conquer (rather than conquered them himself) by showing that the world of plain fact and common detail may be material for poetry”. Although Augustan literature played an important role in Crabbe’s life and poetical career, his body of work is unique and difficult to classify. His best works are an original achievement in a new realistic poetical form. The major factor in Crabbe’s evolving from the Augustan influence to his use of realistic narrative was the changing readership of the late 18th–early 19th century. In the mid-18th century, literature was confined to the aristocratic and highly educated class; with the rise of the middle class at the turn of the 19th century, which came with a growing number of provincial papers, the heightening in production of books in weekly installments, and the establishment of circulating libraries, the need for literature was spread throughout the middle class. Narrative poetry was not a generally accepted mode in Augustan literature, making the narrative form of Crabbe’s mature works an innovation. This was due to some extent to the rise in popularity of the novel in the late 18th–early 19th century. Another innovation is the attention that Crabbe pays to details, both in description and characterization. Augustan critics had espoused the view that minute details should be avoided in favor of generality. Crabbe also broke with Augustan tradition by not dealing with exalted and aristocratic characters, but rather choosing people from middle and working-class society. Poor characters like Crabbe’s often anthologized “Peter Grimes” from The Borough would have been completely unacceptable to Augustan critics. In this way, Crabbe created a new way of presenting life and society in poetry. Criticism Wordsworth predicted that Crabbe’s poetry would last “from its combined merits as truth and poetry fully as long as anything that has been expressed in verse since it first made its appearance”, though on another occasion, according to Henry Crabb Robinson, he “blamed Crabbe for his unpoetical mode of considering human nature and society.” This last opinion was also held by William Hazlitt, who complained that Crabbe’s characters “remind one of anatomical preservations; or may be said to bear the same relation to actual life that a stuffed cat in a glass-case does to the real one purring on the hearth.” Byron, besides what he said in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, declared, in 1816, that he considered Crabbe and Coleridge “the first of these times in point of power and genius.” Byron had felt that English poetry had been steadily on the decline since the depreciation of Pope, and pointed to Crabbe as the last remaining hope of a degenerate age. Other admirers included Jane Austen, Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Sir Walter Scott, who used numerous quotes from Crabbe’s poems in his novels. During Scott’s final illness, Crabbe was the last writer he asked to have read to him. Lord Byron admired Crabbe’s poetry, and called him “nature’s sternest painter, yet the best”. According to critic Frank Whitehead, “Crabbe, in his verse tales in particular, is an important—indeed, a major—poet whose work has been and still is seriously undervalued.” His early poems, which were non-narrative essays in poetical form, gained him the approval of literary men like Samuel Johnson, followed by a period of 20 years in which he wrote much, destroying most of it, and published nothing. In 1807, he published his volume Poems which started off the new realistic narrative method that characterized his poetry for the rest of his career. Whitehead states that this narrative poetry, which occupies the bulk of Crabbe’s output, should be at the center of modern critical attention. Q. D. Leavis said of Crabbe: “He is (or ought to be—for who reads him?) a living classic.” His classic status was also supported by T. S. Eliot in an essay on the poetry of Samuel Johnson in which Eliot grouped Crabbe together favorably with Johnson, Pope, and several other poets. Eliot said that “to have the virtues of good prose is the first and minimum requirement of good poetry.” Critic Arthur Pollard believes that Crabbe definitely met this qualification. Critic William Caldwell Roscoe, answering William Hazlitt’s question of why Crabbe hadn’t in fact written prose rather than verse said “have you ever read Crabbe’s prose? Look at his letters, especially the later ones, look at the correct but lifeless expression of his dedications and prefaces—then look at his verse, and you will see how much he has exceeded 'the minimum requirement of good poetry’.” Critic F. L. Lucas summed up Crabbe’s qualities: "naïve, yet shrewd; straightforward, yet sardonic; blunt, yet tender; quiet, yet passionate; realistic, yet romantic." Crabbe, who is seen as a complicated poet, has been and often still is dismissed as too narrow in his interests and in his way of responding to them in his poetry. “At the same time as the critic is making such judgments, he is all too often aware that Crabbe, nonetheless, defies classification,” says Pollard. Pollard has attempted to examine the negative views of Crabbe and the reasons for limited readership since his lifetime: "Why did Crabbe’s 'realism’ and his discovery of what in effect was the short story in verse fail to appeal to the fiction-dominated Victorian age? Or is it that somehow psychological analysis and poetry are uneasy bedfellows? But then why did Browning succeed and Crabbe descend to the doldrums or to the coteries of admiring enthusiasts? And why have we in this century (the 20th century) failed to get much nearer to him? Does this mean that each succeeding generation must struggle to find his characteristic and essential worth? FitzGerald was only one of many among those who would make 'cullings from’ or 'readings in’ Crabbe. The implications of such selection are clearly that, though much has vanished, much deserves to remain.” Entomology Crabbe was known as a coleopterist and recorder of beetles, and is credited for discovering the first specimen of Calosoma sycophanta L. to be recorded from Suffolk. He published an essay on the Natural History of the Vale of Belvoir in John Nichols’s, Bibliotheca Topographia Britannica, VIII, Antiquities in Leicestershire, 1790. It includes a very extensive list of local coleopterans, and references more than 70 species. Bibliography * Inebriety (published 1775) * The Candidate (published 1780) * The Library (published 1781) * The Village (published 1782) * The Newspaper (published 1785) * Poems (published 1807) * The Borough (published 1810) * Tales in Verse (published 1812) * Tales of the Hall (published 1819) * Posthumous Tales (published 1834) Adaptations * Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes is based on The Borough. Britten also set an extract from The Borough as the third of his Five Flower Songs, op. 47. Charles Lamb’s verse play The Wife’s Trial; or, The Intruding Widow, written in 1827 and published the following year in Blackwood’s Magazine, was based on Crabbe’s tale “The Confidant”. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Crabbe