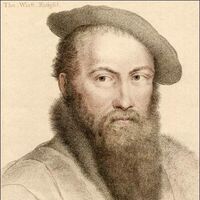

Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503 – 11 October 1542) was a 16th-century English lyrical poet credited with introducing the sonnet into English. He was born at Allington Castle, near Maidstone in Kent – though his family was originally from Yorkshire. His mother was Anne Skinner and his father, Henry Wyatt, had been one of Henry VII's Privy Councillors, and remained a trusted adviser when Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509. In his turn, Thomas Wyatt followed his father to court after his education at St John's College, Cambridge. None of Wyatt's poems were published during his lifetime—the first book to feature his verse was printed a full fifteen years after his death. Education and diplomatic career Wyatt was over six feet tall, reportedly both handsome and physically strong. Wyatt was not only a poet, but also an ambassador in the service of Henry VIII. He first entered Henry's service in 1515 as 'Sewer Extraordinary', and the same year he began studying at St John's College of the University of Cambridge. He married Elizabeth Brooke (1503–1550), the sister of George Brooke, 9th Baron Cobham, in 1522, and a year later she gave birth to a son, Thomas Wyatt, the younger, who led Wyatt's rebellion many years after his father's death. In 1524 Henry VIII assigned Wyatt to be an Ambassador at home and abroad, and some time soon after he separated from his wife on the grounds of adultery. He accompanied Sir John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford to Rome to help petition Pope Clement VII to annul the marriage of Henry VIII to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, an embassy whose goal was to make Henry free to marry Anne Boleyn. According to some, Wyatt was captured by the armies of Emperor Charles V when they captured Rome and imprisoned the Pope in 1527 but managed to escape and then made it back to England. In 1535 Wyatt was knighted and appointed High Sheriff of Kent for 1536. In December 1541 he was elected knight of the shire (M.P.) for Kent. Wyatt's poetry and influence Wyatt's professed object was to experiment with the English tongue, to civilise it, to raise its powers to those of its neighbours. Although a significant amount of his literary output consists of translations of sonnets by the Italian poet Petrarch, he wrote sonnets of his own. Wyatt's sonnets first appeared in Tottle's Miscellany, now on exhibit in the British Library in London. In addition to imitations of works by the classical writers Seneca and Horace, he experimented in stanza forms including the rondeau, epigrams, terza rima, ottava rima songs, satires and also with monorime, triplets with refrains, quatrains with different length of line and rhyme schemes, quatrains with codas, and the French forms of douzaine and treizaine in addition to introducing contemporaries to his poulter's measure form (Alexandrine couplets of twelve syllable iambic lines alternating with a fourteener, fourteen syllable line). and is acknowledged a master in the iambic tetrameter. While Wyatt's poetry reflects classical and Italian models, he also admired the work of Chaucer and his vocabulary reflects Chaucer’s (for example, his use of Chaucer’s word newfangleness, meaning fickle, in They flee from me that sometime did me seek). His best-known poems are those that deal with the trials of romantic love. Others of his poems were scathing, satirical indictments of the hypocrisies and flat-out pandering required of courtiers ambitious to advance at the Tudor court. Wyatt was one of the earliest poets of the Renaissance. He was responsible for many innovations in English poetry. He, along with Surrey, introduced the sonnet from Italy into England. His lyrics show great tenderness of feeling and purity of diction. He is one of the originators of the convention in love poetry according to which the mistress is painted as hard-hearted and cruel. Attribution The Egerton Manuscript, originally an album containing Wyatt's personal selection of his poems and translations, preserves 123 texts, partly in the poet's hand. Tottel's Miscellany (1557), the Elizabethan anthology which created Wyatt's posthumous reputation, ascribes 96 poems to him, (33 not extant in the Egerton Manuscript). These 156 poems can be ascribed to Wyatt with certainty, on the basis of objective evidence. Another 129 poems have been ascribed to Wyatt purely on the basis of subjective editorial judgment. They derive mostly from two Tudor manuscript anthologies, the Devonshire and Blage manuscripts. R A Rebholz in his preface to Sir Thomas Wyatt, The Complete Poems, comments, 'the problem of determining which poems Wyatt wrote is as yet unsolved'. However, as Richard Harrier's The Canon of Sir Thomas Wyatt's Poetry (1975) shows, the problem of determining which poems aren't Wyatt's is much simpler. Harrier examines the documentary evidence of the manuscripts (handwritings, organization, etc.) and establishes that there is insufficient textual warrant for assigning any of these poems to Wyatt. The only basis for ascribing these poems to Wyatt resides in editorial evaluation of their style and poetic merits. Compared with the indubitable standard presented in Wyatt's 156 unquestionably ascribable poems, fewer than 30 of these 129 poems survive scrutiny. Most can be dismissed at once. The best edition of Wyatt thus far is Joost Daalder's (1975). It presents 199 poems, including 25 misascriptions (mostly segregated as "Unascribed") and is missing a dozen poems likely to be Wyatt's. A new edition of this major poet, the inventor of lyric poetry in Modern English, is urgently needed. Assessment Critical opinions of his work have varied widely. Thomas Warton, the eighteenth century critic, considered Wyatt 'confessedly an inferior' to his contemporary Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey and that Wyatt's 'genius was of the moral and didactic species and be deemed the first polished English satirist'. The 20th century saw an awakening in his popularity and a surge in critical attention. C. S. Lewis called him ‘the father of the Drab Age’ (i.e. the unornate), from what Lewis calls the 'golden' age of the 16th century, while others see his love poetry, with its complex use of literary conceits, as anticipating that of the metaphysical poets in the next century. More recently, the critic Patricia Thomson, describes Wyatt as "the Father of English Poetry” Rumored affair with Anne Boleyn Many legends and conjectures have grown up around the notion that the young, unhappily married Wyatt fell in love with the young Anne Boleyn in the early-to-mid 1520s. The exact nature of their relationship remains uncertain today. Their acquaintance is certain. However, whether or not the two shared a romantic relationship is unknown to this day. Nineteenth-century critic Rev. George Gilfillan implies that Wyatt and Boleyn were romantically connected. To quote a modern historian "that they did look into each others eyes, and felt that to each other they were all too lovely.." is a quite possible scenario. In his poetry, Thomas calls his mistress Anna, and often embeds pieces of information that correspond with her life into his poetry. "And now I follow the coals that be quent, From Dover to Calais against my mind..." These lines could refer to Anne's trip to France in 1532 right before her marriage to Henry VIII. This could imply that Thomas followed her to France to try and persuade her otherwise or merely to be with her. Later in his life, Thomas writes, while referring to a woman, "Graven in diamonds with letters plain, There is written her fair neck round about, Noli me tangere, Caesar's, I am;" This shows Wyatt's obvious attraction to a royal lady. According to his grandson George Wyatt, who wrote a biography of Anne Boleyn many years after her death, the moment Thomas Wyatt had seen "this new beauty" on her return from France in winter 1522 he had fallen in love with her. When she attracted King Henry VIII's attentions sometime around 1525, Wyatt was the last of Anne's other suitors to be ousted by the king. According to Wyatt's grandson, after an argument over her during a game of bowls with the King, Wyatt was sent on, or himself requested, a diplomatic mission to Italy. Imprisonment on charges of adultery In May 1536 Wyatt was imprisoned in the Tower of London for allegedly committing adultery with Anne Boleyn. He was released from the Tower later that year, thanks to his friendship or his father's friendship with Thomas Cromwell, and he returned to his duties. During his stay in the Tower he may have witnessed not only the execution of Anne Boleyn (May 19, 1536) from his cell window but also the prior executions of the five men with whom she was accused of adultery. Wyatt is known to have written a poem inspired by the experience, which, though it stays clear of declaring the executions groundless, expresses grief and shock. In the 1530s, he wrote poetry in the Devonshire MS declaring his love for a woman; employing the basic acrostic formula, the first letter of each line spells out SHELTUN. A reply is written underneath it, signed by Mary Shelton, rejecting him. Mary, Anne Boleyn's first cousin, had been the mistress of Henry VIII between February and August 1535. In 1540 he was again in favor, as evident by the fact that he was granted the site and many of the manorial estates of the dissolved Boxley Abbey. However, in 1541 he was charged again with treason and the charges were again lifted—though only thanks to the intervention of Henry's fifth wife, then-Queen Catherine Howard, and upon the condition of reconciling with his adulterous wife. He was granted a full pardon and restored once again to his duties as ambassador. After the execution of Catherine Howard, there were rumours that Wyatt's wife, Elizabeth, was a possibility for wife number six, despite the fact that she was still married to Wyatt. He became ill not long after, and died on 11 October 1542 around the age of 39, while staying with his friend Sir John Horsey at Clifton Maybank House in Dorset. He is buried in nearby Sherborne Abbey. Descendants and relatives Long after Thomas Wyatt's death, his only son, Thomas Wyatt the younger, led a thwarted rebellion against Henry's daughter, Queen Mary I, for which he was executed. The rebellion's aim was to set the Protestant-minded Elizabeth, the daughter of Anne Boleyn, on the throne. His sister Margaret Wyatt was the mother of Henry Lee of Ditchley, from whom descend the Lees of Virginia, including Robert E. Lee. Thomas Wyatt's great grandson was Virginia Governor Francis Wyatt. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wyatt_(poet)

William Henry Ogilvie (21 August 1869– 30 January 1963) was a Scottish-Australian narrative poet and horseman. He was born near Kelso, Borders, Scotland and arrived in Australia in 1889, returning to Scotland after a decade. He had a deep love of horses and riding and he became interested in the outback. Before long he became an expert station hand, drover and horse breaker, working on such stations as Belalie on the Warrego, and Maaoupe near Penola in South Australia. He was a friend of Harry “Breaker” Morant and was described as a quiet-spoken Scot of medium height, with a fair moustache and red complexion.

Florence Margaret Smith, known as Stevie Smith (20 September 1902– 7 March 1971) was an English poet and novelist. Life Stevie Smith, born Florence Margaret Smith in Kingston upon Hull, was the second daughter of Ethel and Charles Smith. She was called “Peggy” within her family, but acquired the name “Stevie” as a young woman when she was riding in the park with a friend who said that she reminded him of the jockey Steve Donoghue. Her father was a shipping agent, a business that he had inherited from his father. As the company and his marriage began to fall apart, he ran away to sea and Smith saw very little of her father after that. He appeared occasionally on 24-hour shore leave and sent very brief postcards ("Off to Valparaiso, Love Daddy"). When she was three years old she moved with her mother and sister to Palmers Green in North London where Smith would live until her death in 1971. She resented the fact that her father had abandoned his family. Later, when her mother became ill, her aunt Madge Spear (whom Smith called “The Lion Aunt”) came to live with them, raised Smith and her elder sister Molly and became the most important person in Smith’s life. Spear was a feminist who claimed to have “no patience” with men and, as Smith wrote, “she also had 'no patience’ with Hitler”. Smith and Molly were raised without men and thus became attached to their own independence, in contrast to what Smith described as the typical Victorian family atmosphere of “father knows best”. When Smith was five she developed tubercular peritonitis and was sent to a sanatorium near Broadstairs, Kent, where she remained for three years. She related that her preoccupation with death began when she was seven, at a time when she was very distressed at being sent away from her mother. Death and fear fascinated her and provide the subjects of many of her poems. Her mother died when Smith was 16. When suffering from the depression to which she was subject all her life she was so consoled by the thought of death as a release that, as she put it, she did not have to commit suicide. She wrote in several poems that death was “the only god who must come when he is called”. Smith suffered throughout her life from an acute nervousness, described as a mix of shyness and intense sensitivity. In the Poem “A House of Mercy”, she wrote of her childhood house in North London: It was a house of female habitation, Two ladies fair inhabited the house, And they were brave. For although Fear knocked loud Upon the door, and said he must come in, They did not let him in. Smith was educated at Palmers Green High School and North London Collegiate School for Girls. She spent the remainder of her life with her aunt, and worked as private secretary to Sir Neville Pearson with Sir George Newnes at Newnes Publishing Company in London from 1923 to 1953. Despite her secluded life, she corresponded and socialised widely with other writers and creative artists, including Elisabeth Lutyens, Sally Chilver, Inez Holden, Naomi Mitchison, Isobel English and Anna Kallin. After she retired from Sir Neville Pearson’s service following a nervous breakdown she gave poetry readings and broadcasts on the BBC that gained her new friends and readers among a younger generation. Sylvia Plath became a fan of her poetry and sent Smith a letter in 1962, describing herself as “a desperate Smith-addict.” Plath expressed interest in meeting in person but committed suicide soon after sending the letter. Smith was described by her friends as being naive and selfish in some ways and formidably intelligent in others, having been raised by her aunt as both a spoiled child and a resolutely autonomous woman. Likewise, her political views vacillated between her aunt’s Toryism and her friends’ left-wing tendencies. Smith was celibate for most of her life, although she rejected the idea that she was lonely as a result, alleging that she had a number of intimate relationships with friends and family that kept her fulfilled. She never entirely abandoned or accepted the Anglican faith of her childhood, describing herself as a “lapsed atheist”, and wrote sensitively about theological puzzles;"There is a God in whom I do not believe/Yet to this God my love stretches." Her 14-page essay of 1958, “The Necessity of Not Believing”, concludes: “There is no reason to be sad, as some people are sad when they feel religion slipping off from them. There is no reason to be sad, it is a good thing.” Smith died of a brain tumour on 7 March 1971. Her last collection, Scorpion and other Poems was published posthumously in 1972, and the Collected Poems followed in 1975. Three novels were republished and there was a successful play based on her life, Stevie, written by Hugh Whitemore. It was filmed in 1978 by Robert Enders and starred Glenda Jackson and Mona Washbourne. Fiction Smith wrote three novels, the first of which, Novel on Yellow Paper, was published in 1936. Apart from death, common subjects in her writing include loneliness; myth and legend; absurd vignettes, usually drawn from middle-class British life, war, human cruelty and religion. All her novels are lightly fictionalised accounts of her own life, which got her into trouble at times as people recognised themselves. Smith said that two of the male characters in her last book are different aspects of George Orwell, who was close to Smith. There were rumours that they were lovers; he was married to his first wife at the time. Novel on Yellow Paper (Cape, 1936) Smith’s first novel is structured as the random typings of a bored secretary, Pompey. She plays word games, retells stories from classical and popular culture, remembers events from her childhood, gossips about her friends and describes her family, particularly her beloved Aunt. As with all Smith’s novels, there is an early scene where the heroine expresses feelings and beliefs which she will later feel significant, although ambiguous, regret for. In Novel on Yellow Paper that belief is anti-Semitism, where she feels elation at being the “only Goy” at a Jewish party. This apparently throwaway scene acts as a timebomb, which detonates at the centre of the novel when Pompey visits Germany as the Nazis are gaining power. With horror, she acknowledges the continuity between her feeling “Hurray for being a Goy” at the party and the madness that is overtaking Germany. The German scenes stand out in the novel, but perhaps equally powerful is her dissection of failed love. She describes two unsuccessful relationships, first with the German Karl and then with the suburban Freddy. The final section of the novel describes with unusual clarity the intense pain of her break-up with Freddy. Over the Frontier (Cape, 1938) Smith herself dismissed her second novel as a failed experiment, but its attempt to parody popular genre fiction to explore profound political issues now seems to anticipate post-modern fiction. If anti-Semitism was one of the key themes of Novel on Yellow Paper, Over the Frontier is concerned with militarism. In particular, she asks how the necessity of fighting Fascism can be achieved without descending into the nationalism and dehumanisation that fascism represents. After a failed romance the heroine, Pompey, suffers a breakdown and is sent to Germany to recuperate. At this point the novel changes style radically, as Pompey becomes part of an adventure/spy yarn in the style of John Buchan or Dornford Yates. As the novel becomes increasingly dreamlike, Pompey crosses over the frontier to become a spy and soldier. If her initial motives are idealistic, she becomes seduced by the intrigue and, ultimately, violence. The vision Smith offers is a bleak one: “Power and cruelty are the strengths of our lives, and only in their weakness is there love.” The Holiday (Chapman and Hall, 1949) Smith’s final novel is her own favourite, and most fully realised. It is concerned with personal and political malaise in the immediate post-war period. Most of the characters are either employed in the army or civil service in post-war reconstruction, and its heroine, Celia, works for the Ministry as a cryptographer and propagandist. The Holiday describes a series of hopeless relationships. Celia and her cousin Caz are in love, but cannot pursue their affair since it is believed that, because of their parents’ adultery, they are half-brother and sister. Celia’s other cousin Tom is in love with her, Basil is love with Tom, Tom is estranged from his father, Celia’s beloved Uncle Heber, who pines for a reconciliation; and Celia’s best friend Tiny longs for the married Vera. These unhappy, futureless but intractable relationships are mirrored by the novel’s political concerns. The unsustainability of the British Empire and the uncertainty over Britain’s post-war role are constant themes, and many of the characters discuss their personal and political concerns as if they were seamlessly linked. Caz is on leave from Palestine and is deeply disillusioned, Tom goes mad during the war, and it is telling that the family scandal that blights Celia and Caz’s lives took place in India. Just as Pompey’s anti-semitism was tested in Novel on Yellow Paper, so Celia’s traditional nationalism and sentimental support for colonialism is challenged throughout The Holiday. Poetry Smith’s first volume of poetry, the self-illustrated A Good Time Was Had By All, was published in 1937 and established her as a poet. Soon her poems were found in periodicals. Her style was often very dark; her characters were perpetually saying “goodbye” to their friends or welcoming death. At the same time her work has an eerie levity and can be very funny though it is neither light nor whimsical. “Stevie Smith often uses the word 'peculiar’ and it is the best word to describe her effects” (Hermione Lee). She was never sentimental, undercutting any pathetic effects with the ruthless honesty of her humour. “A good time was had by all” itself became a catch phrase, still occasionally used to this day. Smith said she got the phrase from parish magazines, where descriptions of church picnics often included this phrase. This saying has become so familiar that it is recognised even by those who are unaware of its origin. Variations appear in pop culture, including “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” by the Beatles. Though her poems were remarkably consistent in tone and quality throughout her life, their subject matter changed over time, with less of the outrageous wit of her youth and more reflection on suffering, faith and the end of life. Her best-known poem is “Not Waving but Drowning”. She was awarded the Cholmondeley Award for Poets in 1966 and won the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry in 1969. She published nine volumes of poems in her lifetime (three more were released posthumously).

I'm honestly, not a good poet. In fact, I hate writing poetry because my poetry is the absolutely horrible in my eyes but in others, its good. I post my poetry, not to get positive feedback or useful criticism but I post it to share my feelings and have a sense of release in my life. I bottle a lot of my feelings up and sometimes, I get inspiration to write a poem but even when i write a poem, it doesn't feel right. I like sharing my poetry so people can get an insight of my feelings inside and see the stuff, I've went through or am currently going through. Again I am not looking for criticism or really any praise. If you do like my poetry, well then I'm glad. It's usually a shock to me that anyone would take a liking to my poetry and if you don't like my poetry, well then that's something we can both agree on right? ;) ABOUT ME: I live in Charlotte,NC. I am 18 years old. I've been writing poetry ever since my mom died which was 5 years ago.

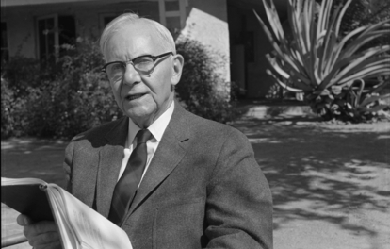

John Crowe Ransom (April 30, 1888– July 3, 1974) was an American educator, scholar, literary critic, poet, essayist and editor. He is considered to be a founder of the New Criticism school of literary criticism. As a faculty member at Kenyon College, he was the first editor of the widely regarded Kenyon Review. Highly respected as a teacher and mentor to a generation of accomplished students, he also was a prize-winning poet and essayist.

David Lehman (born June 11, 1948 in New York City) is a poet and the series editor for The Best American Poetry series. He teaches at The New School in New York City. Career David Lehman grew up the son of European Holocaust refugees in Manhattan’s northernmost neighborhood of Inwood. He attended Stuyvesant High School and Columbia University, and Cambridge University in England on a Kellett Fellowship. On his return to New York, he received a Ph.D. in English from Columbia, where he was Lionel Trilling’s research assistant. Lehman’s poem “The Presidential Years” appeared in The Paris Review No. 43 (Summer, 1968) while he was a Columbia undergraduate. His books of poetry include New and Selected Poems (2013), Yeshiva Boys (November 2009), When a Woman Loves a Man (2005), The Evening Sun (2002), The Daily Mirror (2000), and Valentine Place (1996), all published by Scribner. Princeton University Press published Operation Memory (1990), and An Alternative to Speech (1986). He collaborated with James Cummins on a book of sestinas, Jim and Dave Defeat the Masked Man (Soft Skull Press, 2005), and with Judith Hall on a book of poems and collages, Poetry Forum (Bayeux Arts, 2007). Since 2009, new poems have been published in 32 Poems, The Atlantic, The Awl, Barrow Street, The Common, Green Mountains Review, Hanging Loose, Hot Street, New Ohio Review, The New Yorker, Poetry, Poetry London, Sentence, Smartish Pace, Slate, and The Yale Review. Lehman’s poems appear in Chinese in the bilingual anthology, Contemporary American Poetry, published through a partnership between the NEA and the Chinese government, and in the Mongolian-English Anthology of American Poetry. Lehman’s work has been translated into sixteen languages overall, including Spanish, French, German, Danish, Russian, Polish, Korean and Japanese. In 2013, his translation of Goethe’s “Wandrers Nachtlied” into English appeared under the title “Goethe’s Nightsong” in The New Republic, and his translation of Guillaume Apollinaire’s “Zone” was published with an introductory essay in Virginia Quarterly Review. The translation and commentary won the journal’s Emily Clark Balch Prize for 2014. Additionally, his poem, “French Movie” appears in the third season of Motionpoems. Lehman is the series editor of The Best American Poetry, which he initiated in 1988. Lehman has edited The Oxford Book of American Poetry (Oxford University Press, 2006), The Best American Erotic Poems: From 1800 to the Present (Scribner, 2008), and Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present (Scribner, 2003). He is the author of six nonfiction books, including, most recently, A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters, American Songs (Nextbook, 2009), for which he received a 2010 ASCAP Deems Taylor award from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. Sponsored by the American Library Association, Lehman curated, wrote, and designed a traveling library exhibit based on his book A Fine Romance that toured 55 libraries in 25 states between May 2011 and April 2012 with appearances at three libraries in New York state and Maryland. In an interview published in Smithsonian Magazine, Lehman discusses the artistry of the great lyricists: “The best song lyrics seem to me so artful, so brilliant, so warm and humorous, with both passion and wit, that my admiration is matched only by my envy... these lyricists needed to work within boundaries, to get complicated emotions across and fit the lyrics to the music, and to the mood thereof. That takes genius.” Lehman’s other books of criticism include The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets (Doubleday, 1998), which was named a "Book to Remember 1999" by the New York Public Library; The Big Question (1995); The Line Forms Here (1992) and Signs of the Times: Deconstruction and the Fall of Paul de Man (1991). His study of detective novels, The Perfect Murder (1989), was nominated for an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. A new edition of The Perfect Murder appeared in 2000. In October, 2015, he published Sinatra’s Century: One Hundred Notes on the Man and His World. Lehman worked as a free-lance journalist for many years. His by-line appeared frequently in Newsweek in the 1980s and he has written on a variety of subjects for journals ranging from the New York Times, the Washington Post, People, and The Wall Street Journal to The American Scholar, The Academy of American Poets, National Public Radio, Salon, Slate, Smithsonian, and Art in America. The Library of Congress commissioned an essay from Lehman, “Peace and War in American Poetry,” and posted it online in April 2013. In 2013, Lehman wrote the introduction to The Collected Poems of Joseph Ceravolo. He had previously written introductory essays to books by A. R. Ammons, Kenneth Koch, Philip Larkin, Alfred Leslie, Fairfield Porter, Karl Shapiro, and Mark Van Doren. In 1994 he succeeded Donald Hall as the general editor of the University of Michigan Press’s Poets on Poetry series, a position he held for twelve years. In 1997 he teamed with Star Black in creating and directing the famed KGB Bar Monday night poetry series in New York City’s East Village. Lehman and Black co-edited The KGB Bar Book of Poems (HarperCollins, 2000). They directed the reading series until 2003. He has taught in the graduate writing program of the New School in New York City since the program’s inception in 1996 and has served as poetry coordinator since 2003. In an interview with Tom Disch in the Cortland Review, Lehman addresses his great variety of poetic styles: “I write in a lot of different styles and forms on the theory that the poems all sound like me in the end, so why not make them as different from one another as possible, at least in outward appearance? If you write a new poem every day, you will probably have by the end of the year, if you’re me, an acrostic, an abecedarium, a sonnet or two, a couple of prose poems, poems that have arbitrary restrictions, such as the one I did that has only two words per line.” At the request of the editors of The American Scholar, Lehman initiated “Next Line, Please,” a poetry-writing contest, on the magazine’s website. The first project was a crowd-sourced sonnet, “Monday,” which was completed in August 2014. There followed a haiku, a tanka, an anagram based on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s middle name, a couplet (which grew into a “sonnet ghazal”), and a “shortest story” competition. Lehman devises the puzzles—or prompts—and judges the results. Lehman has been awarded fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Ingram Merrill Foundation, and the NEA, and received an award in literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Writer’s Award. He has lectured widely in the United States and abroad. Lehman divides his time between Ithaca, New York, and New York City. He is married to Stacey Harwood. Bibliography * works written by David Lehman: * Sinatra’s Century: One Hundred Notes on the Man and His World (2015) * New and Selected Poems (2013) * A Fine Romance (2009) * Yeshiva Boys (2009) * When a Woman Loves a Man (Scribner, 2005) * The Evening Sun (Scribner, 2002) * The Daily Mirror: A Journal in Poetry (2000) * The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets (1998) * Valentine Place (1996) * The Big Question (1995) * The Line Forms Here (1992) * Signs of the Times: Deconstruction and the Fall of Paul de Man (1991) * Operation Memory (1990) * The Perfect Murder: A Study in Detection (1989) * An Alternative to Speech (1986) * Beyond Amazement: New Essays on John Ashbery (1980) * works edited by David Lehman: * The Best American Erotic Poems (2008) * The Oxford Book of American Poetry (2006) * A. R. Ammons: Selected Poems (2006) * Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present (2003) * Ecstatic Occasions, Expedient Forms: 85 Leading Contemporary Poets Select and Comment on Their Poems (1987, expanded 1996) * The Best American Poetry with guest editors: * Terrance Hayes (2014), Denise Duhamel (2013), Mark Doty (2012), Kevin Young (2011), Amy Gerstler (2010), David Wagoner (2009), Charles Wright (2008), Heather McHugh (2007), Billy Collins (2006), Paul Muldoon (2005), Lyn Hejinian (2004), Yusef Komunyakaa (2003), Robert Creeley (2002), Robert Hass (2001), Rita Dove (2000), Robert Bly (1999), John Hollander (1998), James Tate (1997), Adrienne Rich (1996), Richard Howard (1995), A.R. Ammons (1994), Louise Glück (1993), Charles Simic (1992), Mark Strand (1991), Jorie Graham (1990), Donald Hall (1989) and John Ashbery (1988). * works written collaboratively: * Poetry Forum: A Play Poem: A Pl’em with Judith Hall (Bayeux Arts, 2007) * Jim and Dave Defeat the Masked Man with James Cummins (Soft Skull Press, 2005) * works edited collaboratively: * The Best of the Best American Poetry: 25th Anniversary Edition with Robert Pinsky (Scribner, 2013) * The KGB Bar Book of Poems with Star Black (HarperCollins, 2000) * The Best of the Best American Poetry, 1988-1997 with Harold Bloom (Scribner, 1998) * James Merrill: Essays in Criticism with Charles Berger (Cornell University Press, 1983) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Lehman

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, KG (1516/1517– 19 January 1547), was an English aristocrat, and one of the founders of English Renaissance poetry. He was a first cousin of both Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, the second and fifth wives of King Henry VIII. Life He was the eldest son of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and his second wife, the former Lady Elizabeth Stafford (daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham), so he was descended from kings on both sides of his family tree: King Edward I on his father’s side and King Edward III on his mother’s side. He was reared at Windsor with Henry VIII’s illegitimate son Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset, and they became close friends and, later, brothers-in-law upon the marriage of Surrey’s sister to Fitzroy. Like his father and grandfather, he was a brave and able soldier, serving in Henry VIII’s French wars as “Lieutenant General of the King on Sea and Land.” He was repeatedly imprisoned for rash behaviour, on one occasion for striking a courtier, on another for wandering through the streets of London breaking the windows of sleeping people. He became Earl of Surrey in 1524 when his grandfather died and his father became Duke of Norfolk. In 1532 he accompanied his first cousin Anne Boleyn, the King, and the Duke of Richmond to France, staying there for more than a year as a member of the entourage of Francis I of France. In 1536 his first son, Thomas (later 4th Duke of Norfolk), was born, Anne Boleyn was executed on charges of adultery and treason, and the Duke of Richmond died at the age of 17 and was buried at one of the Howard homes, Thetford Abbey. In 1536 Surrey also served with his father against the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion protesting against the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Literary activity and legacy He and his friend Sir Thomas Wyatt were the first English poets to write in the sonnet form that Shakespeare later used, and Surrey was the first English poet to publish blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) in his translation of the second and fourth books of Virgil’s Aeneid. Together, Wyatt and Surrey, due to their excellent translations of Petrarch’s sonnets, are known as “Fathers of the English Sonnet”. While Wyatt introduced the sonnet into English, it was Surrey who gave them the rhyming meter and the division into quatrains that now characterizes the sonnets variously named English, Elizabethan or Shakespearean sonnets. Death and burial Henry VIII, consumed by paranoia and increasing illness, became convinced that Surrey had planned to usurp the crown from his son Edward. The King had Surrey imprisoned—with his father—sentenced to death on 13 January 1547, and beheaded for treason on 19 January 1547 (his father survived impending execution only by it being set for the day after the king happened to die, though he remained imprisoned). Surrey’s son Thomas became heir to the dukedom of Norfolk instead, inheriting it on the 3rd duke’s death in 1554. He is buried in a spectacular painted alabaster tomb in the church of St Michael the Archangel, Framlingham. Marriage and issue He married Frances de Vere, the daughter of John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford, and Elizabeth Trussell. They had two sons and three daughters: Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk (10 March 1536– 2 June 1572), married (1) Mary FitzAlan (2) Margaret Audley (3) Elizabeth Leyburne. Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, who died unmarried. Jane Howard, who married Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland. Margaret Howard, who married Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton. Katherine Howard, who married Henry Berkeley, 7th Baron Berkeley. In popular culture Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey was portrayed by actor David O’Hara in The Tudors, a television series which ran from 2007 to 2010. Ancestry References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Howard,_Earl_of_Surrey

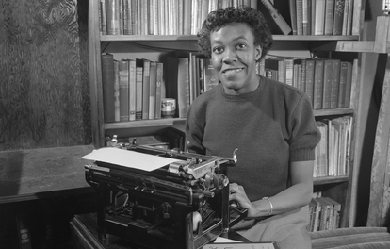

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks (June 7, 1917– December 3, 2000) was an American poet and teacher. She was the first African-American woman to win a Pulitzer prize when she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1950 for her second collection, Annie Allen. Throughout her career she received many more honors. She was appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1968, a position held until her death and Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985.

Augusta Webster (30 January 1837 - 5 September 1894) born in Poole, Dorset as Julia Augusta Davies, was an English poet, dramatist, essayist, and translator. The daughter of Vice-admiral George Davies and Julia Hume she spent her younger years on board the ship he was stationed, the Griper. She studied Greek at home, taking a particular interest in Greek drama, and went on to study at the Cambridge School of Art. She published her first volume of poetry in 1860 under the pen name Cecil Homes. In 1863 she married Thomas Webster, a fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge. They had a daughter, Augusta Georgiana, who married Reverend George Theobald Bourke, a younger son of the Joseph Bourke, 3rd Earl of Mayo. Much of Webster’s writing explored the condition of women, and she was a strong advocate of women’s right to vote, working for the London branch of the National Committee for Women’s Suffrage. Webster was the first female writer to hold elective office, having been elected to the London School Board in 1879 and 1885. In 1885 she travelled to Italy in an attempt to improve her failing health. She died on September 5, 1894, at 57. During her lifetime her writing was acclaimed and she was considered by some the successor to Elizabeth Barrett Browning. After her death, however, her reputation quickly declined. Since the mid-1990s she has gained increasing critical attention from scholars such as Isobel Armstrong, Angela Leighton, and Christine Sutphin, Her best-known poems include three long dramatic monologues spoken by women: “A Castaway,” “Circe”, and “The Happiest Girl In The World”, as well as a posthumously published sonnet-sequence, “Mother and Daughter”.

My name is janessa jordan I was born in brooklyn new york and went to school in manhattan new york I use to sing on a church choir at st.barts I like to write poetry books and also enjoy my personal life party,work, shopping,go out to eat ect,basically have fun in life with family and friends :). You can find my books on sale now at http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/nessa212 Or http://www.barnsandnoble.com author name janessa jordan Book title: the gifted poetry writer Book title: poetry of art Book title: the eagles eyes of poetry Book title: the ending of hell and entry into Heavens life of poetry Book title: the Christmas new year poetry Book title: janessa beauty in poetry Book title: sex poetry and a written book novel Book title: the undertaker killing women Book title: the beginning of a new life Book title: the secret love affair Book title: the imitations Book title: why do you love me poetry Thank you have a bless day.

Richard Purdy Wilbur (born March 1, 1921) is an American poet and literary translator. He was appointed the second Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1987, and twice received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, in 1957 and again in 1989. Biography Early years Wilbur was born in New York City March 1, 1921 and grew up in North Caldwell, New Jersey. He graduated from Montclair High School in 1938, having worked on the school newspaper as a student there. He graduated from Amherst College in 1942 and then served in the United States Army from 1943 to 1945 during World War II. After the Army and graduate school at Harvard University, Wilbur taught at Wellesley College, then Wesleyan University for two decades and at Smith College for another decade. At Wesleyan, he was instrumental in founding the award-winning poetry series of the University Press. He received two Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry and, as of 2009, teaches at Amherst College. He is also on the editorial board of the literary magazine The Common, based at Amherst College. Career When only 8 years old, Wilbur published his first poem in John Martin’s Magazine. His first book, The Beautiful Changes and Other Poems, appeared in 1947. Since then he has published several volumes of poetry, including New and Collected Poems (Faber, 1989). Wilbur is also a translator, specializing in the 17th century French comedies of Molière and the dramas of Jean Racine. His translation of Tartuffe has become the standard English version of the play, and has been presented on television twice (a 1978 production is available on DVD.) In addition to publishing poetry and translations, he has also published several children’s books including Opposites, More Opposites, and The Disappearing Alphabet. Continuing the tradition of Robert Frost and W. H. Auden, Wilbur’s poetry finds illumination in everyday experiences. Less well-known is Wilbur’s foray into lyric writing. He provided lyrics to several songs in Leonard Bernstein’s 1956 musical, Candide, including the famous “Glitter and Be Gay” and “Make Our Garden Grow.” He has also produced several unpublished works including “The Wing” and “To Beatrice”. His honors include the 1983 Drama Desk Special Award and the PEN Translation Prize for his translation of The Misanthrope, both the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the National Book Award for Things of This World (1956), the Edna St Vincent Millay award, the Bollingen Prize, and the Chevalier, Ordre des Palmes Académiques. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1959. In 1987 Wilbur became the second poet, after Robert Penn Warren, to be named U.S. Poet Laureate after the position’s title was changed from Poetry Consultant. In 1988, he won the Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry and then in 1989 he won a second Pulitzer, this one for his New and Collected Poems. On October 14, 1994, he received the National Medal of Arts from President Bill Clinton. He also received the PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation in 1994. In 2003, Wilbur was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame. In 2006, Wilbur won the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. In 2010 he won the National Translation Award for the translation of The Theatre of Illusion by Pierre Corneille. In 2012, Yale conferred an honorary degree, Doctor of Letters, on Wilbur. Bibliography Poetry collections * 1947: The Beautiful Changes, and Other Poems * 1950: Ceremony, and Other Poems * 1955: A Bestiary * 1956: Things of This World - won Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and National Book Award, both in 1957 * 1961: Advice to a Prophet, and Other Poems * 1969: Walking to Sleep: New Poems and Translations * 1976: The Mind-Reader: New Poems * 1988: New and Collected Poems - won Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1989 * 2000: Mayflies: New Poems and Translations * 2004: Collected Poems, 1943–2004 * 2010: Anterooms * 2012: The Nutcracker Selected poems available online Prose collections * 1976: Responses: Prose Pieces, 1953–1976 * 1997: The Catbird’s Song: Prose Pieces, 1963–1995 Translated plays from other authors Translated from Molière * The Misanthrope (1955/1666) * Tartuffe (1963/1669) * The School for Wives (1971/1662) * The Learned Ladies (1978/1672) * School for Husbands (1992/1661) * The Imaginary Cuckold, or Sganarelle (1993/1660) * Amphitryon (1995/1668) * The Bungler (2000/1655) * Don Juan (2001/1665) * Lovers’ Quarrels (2009/1656) From Jean Racine * Andromache (1982/1667) * Phaedra (1986/1677) * The Suitors (2001/1668) From Pierre Corneille * The Theatre of Illusion (2007/1636) * Le Cid (2009/1636) * The Liar (2009/1643) Sources * President and first Lady honor Artists and Scholars, Clinton, The White House– Office of the Press Secretary, 1994-10-13 . References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Wilbur

Most of what I write or enjoy reading has a significant amount of word relationships and phrasing that evoke imagery. Whether it's prose on people or life or metered rhyming verses I find that the way they read should have not just metaphor, word plays, and all other typical "poetic" usage, but should also have a visual quality that is some what like painting or illustration. I'm not saying I do this well in my own writing but I'm merely stating what I am going for as an artist. Like anything creative, the more of yourself you put into it and dedicate time to, the better it ultimately becomes. The collection of poems that are subtitled Nest in the Black Tree is a series of concept pieces. The setting is in the Bad Lands (purgatory). When a "Soul" has been born it belongs to the Watch Tower(God). Once one is created the Clock Maker creates a "vessel"(a human body). The Time Keeper starts the Heart-Break-Timer and this would be the life one is given from begining, life, old age, and the end. When the timer runs out the soul must be delivered back to the Watch Tower, but to do so is tasked by the Sprinter(an angel). The Sprinter takes the soul across the Bad Lands running as God's Speed. The Bad Lands are filled by an evil race known as the Wretched. The Wretches are ruled by the war machine Brontus Singlairn. Brontus wants the souls the Sprinters carry to turn them from a life into a Wretch(demon). The Poems are free-verse prose left open to to the imagination of the reader and to the foundation of the story. "Space, Universe, Stars" are part of the idea of creating a setting, being that this is a place of the in "between", and also is a way to give a little more poetic depth. One day I would hope to get the "The Nest and the Black Tree" published. This is where you, the reader, comes in to give me comments and ideas for this evolving story. —Nicholas Gress —Saidwhattha

Henry James Pye (/paɪ/; 10 February 1744– 11 August 1813) was an English poet. Pye was Poet Laureate from 1790 until his death. He was the first poet laureate to receive a fixed salary of £27 instead of the historic tierce of Canary wine (though it was still a fairly nominal payment; then as now the Poet Laureate had to look to extra sales generated by the prestige of the office to make significant money from the Laureateship). Life Pye was born in London, the son of Henry Pye of Faringdon House in Berkshire, and his wife, Mary James. He was the nephew of Admiral Thomas Pye. He was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford. His father died in 1766, leaving him a legacy of debt amounting to £50,000, and the burning of the family home further increased his difficulties. In 1784 he was elected Member of Parliament for Berkshire. He was obliged to sell the paternal estate, and, retiring from Parliament in 1790, became a police magistrate for Westminster. Although he had no command of language and was destitute of poetic feeling, his ambition was to obtain recognition as a poet, and he published many volumes of verse. Of all he wrote his prose Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) is most worthy of record. He was made poet laureate in 1790, perhaps as a reward for his faithful support of William Pitt the Younger in the House of Commons. The appointment was looked on as ridiculous, and his birthday odes were a continual source of contempt. The 20th century British historian Lord Blake called Pye “the worst Poet Laureate in English history with the possible exception of Alfred Austin.” Indeed, Pye’s successor, Robert Southey, wrote in 1814: “I have been rhyming as doggedly and dully as if my name had been Henry James Pye.” After his death, Pye remained one of the unfortunate few who have been classified as a “poetaster.” As a prose writer, Pye was far from contemptible. He had a fancy for commentaries and summaries. His “Commentary on Shakespeare’s commentators”, and that appended to his translation of the Poetics, contain some noteworthy matter. A man, who, born in 1745, could write “Sir Charles Grandison is a much more unnatural character than Caliban,” may have been a poetaster but was certainly not a fool. He died in Pinner, Middlesex on 11 August 1813. Pye married twice. He had two daughters by his first wife. He married secondly in 1801 Martha Corbett, by whom he had a son Henry John Pye, who in 1833 inherited the Clifton Hall, Staffordshire estate of a distant cousin and who was High Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1840. Works Prose * Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) * The Democrat (1795) * The Aristocrat (1799) Poetry * Poems on Various Subjects (1787), first substantial collection of Pye’s verse * Adelaide: a Tragedy in Five Acts (1800) * Alfred (1801) Translations * Aristotle’s Poetics (1792) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_James_Pye

Daniel Defoe (c. 1660 – 24 April 1731), born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel Robinson Crusoe, which is second only to the Bible in its number of translations. He has been seen as one of the earliest proponents of the English novel, and helped to popularise the form in Britain with others such as Aphra Behn and Samuel Richardson. Defoe wrote many political tracts and often was in trouble with the authorities, including a spell in prison. Intellectuals and political leaders paid attention to his fresh ideas and sometimes consulted with him. Defoe was a prolific and versatile writer, producing more than three hundred works—books, pamphlets, and journals—on diverse topics, including politics, crime, religion, marriage, psychology, and the supernatural. He was also a pioneer of business journalism and economic journalism. Early life Daniel Foe (his original name) was probably born in Fore Street in the parish of St Giles Cripplegate, London. Defoe later added the aristocratic-sounding “De” to his name, and on occasion claimed descent from the family of De Beau Faux. His birthdate and birthplace are uncertain, and sources offer dates from 1659 to 1662, with the summer or early autumn of 1660 considered the most likely. His father, James Foe, was a prosperous tallow chandler and a member of the Worshipful Company of Butchers. In Defoe’s early life, he experienced some of the most unusual occurrences in English history: in 1665, 70,000 were killed by the Great Plague of London, and the next year, the Great Fire of London left standing only Defoe’s and two other houses in his neighbourhood. In 1667, when he was probably about seven, a Dutch fleet sailed up the Medway via the River Thames and attacked the town of Chatham in the raid on the Medway. His mother, Annie, had died by the time he was about ten. Education Defoe was educated at the Rev. James Fisher’s boarding school in Pixham Lane in Dorking, Surrey. His parents were Presbyterian dissenters, and around the age of 14, he attended a dissenting academy at Newington Green in London run by Charles Morton, and he is believed to have attended the Newington Green Unitarian Church and kept practising his Presbyterian religion. During this period, the English government persecuted those who chose to worship outside the Church of England. Business career Defoe entered the world of business as a general merchant, dealing at different times in hosiery, general woollen goods, and wine. His ambitions were great and he was able to buy a country estate and a ship (as well as civets to make perfume), though he was rarely out of debt. He was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1692. On 1 January 1684, Defoe married Mary Tuffley at St Botolph’s Aldgate. She was the daughter of a London merchant, receiving a dowry of £3,700—a huge amount by the standards of the day. With his debts and political difficulties, the marriage may have been troubled, but it lasted 47 years and produced eight children.In 1685, Defoe joined the ill-fated Monmouth Rebellion but gained a pardon, by which he escaped the Bloody Assizes of Judge George Jeffreys. Queen Mary and her husband William III were jointly crowned in 1689, and Defoe became one of William’s close allies and a secret agent. Some of the new policies led to conflict with France, thus damaging prosperous trade relationships for Defoe, who had established himself as a merchant. In 1692, Defoe was arrested for debts of £700, though his total debts may have amounted to £17,000. His laments were loud and he always defended unfortunate debtors, but there is evidence that his financial dealings were not always honest. He died with little wealth and evidence of lawsuits with the royal treasury.Following his release, he probably travelled in Europe and Scotland, and it may have been at this time that he traded wine to Cadiz, Porto and Lisbon. By 1695, he was back in England, now formally using the name “Defoe” and serving as a “commissioner of the glass duty”, responsible for collecting taxes on bottles. In 1696, he ran a tile and brick factory in what is now Tilbury in Essex and lived in the parish of Chadwell St Mary. Writing As many as 545 titles have been ascribed to Defoe, ranging from satirical poems, political and religious pamphlets, and volumes. (Furbank and Owens argue for the much smaller number of 276 published items in Critical Bibliography (1998).) Pamphleteering and prison Defoe’s first notable publication was An essay upon projects, a series of proposals for social and economic improvement, published in 1697. From 1697 to 1698, he defended the right of King William III to a standing army during disarmament, after the Treaty of Ryswick (1697) had ended the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697). His most successful poem, The True-Born Englishman (1701), defended the king against the perceived xenophobia of his enemies, satirising the English claim to racial purity. In 1701, Defoe presented the Legion’s Memorial to Robert Harley, then Speaker of the House of Commons—and his subsequent employer—while flanked by a guard of sixteen gentlemen of quality. It demanded the release of the Kentish petitioners, who had asked Parliament to support the king in an imminent war against France. The death of William III in 1702 once again created a political upheaval, as the king was replaced by Queen Anne who immediately began her offensive against Nonconformists. Defoe was a natural target, and his pamphleteering and political activities resulted in his arrest and placement in a pillory on 31 July 1703, principally on account of his December 1702 pamphlet entitled The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters; Or, Proposals for the Establishment of the Church, purporting to argue for their extermination. In it, he ruthlessly satirised both the High church Tories and those Dissenters who hypocritically practised so-called “occasional conformity”, such as his Stoke Newington neighbour Sir Thomas Abney. It was published anonymously, but the true authorship was quickly discovered and Defoe was arrested. He was charged with seditious libel. Defoe was found guilty after a trial at the Old Bailey in front of the notoriously sadistic judge Salathiel Lovell. Lovell sentenced him to a punitive fine of 200 marks, to public humiliation in a pillory, and to an indeterminate length of imprisonment which would only end upon the discharge of the punitive fine. According to legend, the publication of his poem Hymn to the Pillory caused his audience at the pillory to throw flowers instead of the customary harmful and noxious objects and to drink to his health. The truth of this story is questioned by most scholars, although John Robert Moore later said that “no man in England but Defoe ever stood in the pillory and later rose to eminence among his fellow men”. After his three days in the pillory, Defoe went into Newgate Prison. Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, brokered his release in exchange for Defoe’s co-operation as an intelligence agent for the Tories. In exchange for such co-operation with the rival political side, Harley paid some of Defoe’s outstanding debts, improving his financial situation considerably.Within a week of his release from prison, Defoe witnessed the Great Storm of 1703, which raged through the night of 26/27 November. It caused severe damage to London and Bristol, uprooted millions of trees, and killed more than 8,000 people, mostly at sea. The event became the subject of Defoe’s The Storm (1704), which includes a collection of witness accounts of the tempest. Many regard it as one of the world’s first examples of modern journalism.In the same year, he set up his periodical A Review of the Affairs of France which supported the Harley Ministry, chronicling the events of the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1714). The Review ran three times a week without interruption until 1713. Defoe was amazed that a man as gifted as Harley left vital state papers lying in the open, and warned that he was almost inviting an unscrupulous clerk to commit treason; his warnings were fully justified by the William Gregg affair. When Harley was ousted from the ministry in 1708, Defoe continued writing the Review to support Godolphin, then again to support Harley and the Tories in the Tory ministry of 1710–1714. The Tories fell from power with the death of Queen Anne, but Defoe continued doing intelligence work for the Whig government, writing “Tory” pamphlets that undermined the Tory point of view.Not all of Defoe’s pamphlet writing was political. One pamphlet was originally published anonymously, entitled "A True Relation of the Apparition of One Mrs. Veal the Next Day after her Death to One Mrs. Bargrave at Canterbury the 8th of September, 1705." It deals with interaction between the spiritual realm and the physical realm and was most likely written in support of Charles Drelincourt’s The Christian Defense against the Fears of Death (1651). It describes Mrs. Bargrave’s encounter with her old friend Mrs. Veal after she had died. It is clear from this piece and other writings that the political portion of Defoe’s life was by no means his only focus. Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707 In despair during his imprisonment for the seditious libel case, Defoe wrote to William Paterson, the London Scot and founder of the Bank of England and part instigator of the Darien scheme, who was in the confidence of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, leading minister and spymaster in the English Government. Harley accepted Defoe’s services and released him in 1703. He immediately published The Review, which appeared weekly, then three times a week, written mostly by himself. This was the main mouthpiece of the English Government promoting the Act of Union 1707.In 1709, Defoe authored a rather lengthy book entitled The History of the Union of Great Britain, an Edinburgh publication printed by the Heirs of Anderson. The book was not published anonymously and cites Defoe twice as being its author. The book attempts to explain the facts leading up to the Act of Union 1707, dating all the way back to 6 December 1604 when King James I was presented with a proposal for unification. This so-called “first draft” for unification took place 100 years before the signing of the 1707 accord, which respectively preceded the commencement of Robinson Crusoe by another ten years. Defoe began his campaign in The Review and other pamphlets aimed at English opinion, claiming that it would end the threat from the north, gaining for the Treasury an “inexhaustible treasury of men”, a valuable new market increasing the power of England. By September 1706, Harley ordered Defoe to Edinburgh as a secret agent to do everything possible to help secure acquiescence in the Treaty of Union. He was conscious of the risk to himself. Thanks to books such as The Letters of Daniel Defoe (edited by G. H. Healey, Oxford 1955), far more is known about his activities than is usual with such agents. His first reports included vivid descriptions of violent demonstrations against the Union. “A Scots rabble is the worst of its kind”, he reported. Years later John Clerk of Penicuik, a leading Unionist, wrote in his memoirs that it was not known at the time that Defoe had been sent by Godolphin: … to give a faithful account to him from time to time how everything past here. He was therefor a spy among us, but not known to be such, otherways the Mob of Edin. had pull him to pieces. Defoe was a Presbyterian who had suffered in England for his convictions, and as such he was accepted as an adviser to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland and committees of the Parliament of Scotland. He told Harley that he was “privy to all their folly” but “Perfectly unsuspected as with corresponding with anybody in England”. He was then able to influence the proposals that were put to Parliament and reported, Having had the honour to be always sent for the committee to whom these amendments were referrèd, I have had the good fortune to break their measures in two particulars via the bounty on Corn andproportion of the Excise. For Scotland, he used different arguments, even the opposite of those which he used in England, usually ignoring the English doctrine of the Sovereignty of Parliament, for example, telling the Scots that they could have complete confidence in the guarantees in the Treaty. Some of his pamphlets were purported to be written by Scots, misleading even reputable historians into quoting them as evidence of Scottish opinion of the time. The same is true of a massive history of the Union which Defoe published in 1709 and which some historians still treat as a valuable contemporary source for their own works. Defoe took pains to give his history an air of objectivity by giving some space to arguments against the Union but always having the last word for himself. He disposed of the main Union opponent, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, by ignoring him. Nor does he account for the deviousness of the Duke of Hamilton, the official leader of the various factions opposed to the Union, who seemingly betrayed his former colleagues when he switched to the Unionist/Government side in the decisive final stages of the debate. Defoe made no attempt to explain why the same Parliament of Scotland which was so vehement for its independence from 1703 to 1705 became so supine in 1706. He received very little reward from his paymasters and of course no recognition for his services by the government. He made use of his Scottish experience to write his Tour thro’ the whole Island of Great Britain, published in 1726, where he admitted that the increase of trade and population in Scotland which he had predicted as a consequence of the Union was “not the case, but rather the contrary”. Defoe’s description of Glasgow (Glaschu) as a “Dear Green Place” has often been misquoted as a Gaelic translation for the town’s name. The Gaelic Glas could mean grey or green, while chu means dog or hollow. Glaschu probably means “Green Hollow”. The “Dear Green Place”, like much of Scotland, was a hotbed of unrest against the Union. The local Tron minister urged his congregation “to up and anent for the City of God”. The “Dear Green Place” and “City of God” required government troops to put down the rioters tearing up copies of the Treaty at almost every mercat cross in Scotland. When Defoe visited in the mid-1720s, he claimed that the hostility towards his party was “because they were English and because of the Union, which they were almost universally exclaimed against”. Late writing The extent and particulars are widely contested concerning Defoe’s writing in the period from the Tory fall in 1714 to the publication of Robinson Crusoe in 1719. Defoe comments on the tendency to attribute tracts of uncertain authorship to him in his apologia Appeal to Honour and Justice (1715), a defence of his part in Harley’s Tory ministry (1710–1174). Other works that anticipate his novelistic career include The Family Instructor (1715), a conduct manual on religious duty; Minutes of the Negotiations of Monsr. Mesnager (1717), in which he impersonates Nicolas Mesnager, the French plenipotentiary who negotiated the Treaty of Utrecht (1713); and A Continuation of the Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy (1718), a satire of European politics and religion, ostensibly written by a Muslim in Paris. From 1719 to 1724, Defoe published the novels for which he is famous (see below). In the final decade of his life, he also wrote conduct manuals, including Religious Courtship (1722), The Complete English Tradesman (1726) and The New Family Instructor (1727). He published a number of books decrying the breakdown of the social order, such as The Great Law of Subordination Considered (1724) and Everybody’s Business is Nobody’s Business (1725) and works on the supernatural, like The Political History of the Devil (1726), A System of Magick (1727) and An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions (1727). His works on foreign travel and trade include A General History of Discoveries and Improvements (1727) and Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis (1728). Perhaps his greatest achievement with the novels is the magisterial A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain (1724–1727), which provided a panoramic survey of British trade on the eve of the Industrial Revolution. The Complete English Tradesman Published in 1726, The Complete English Tradesman is an example of Defoe’s political works. He discusses the role of the tradesman in England in comparison to tradesmen internationally, arguing that the British system of trade is far superior. He also implies that trade is the backbone of the British economy: “estate’s a pond, but trade’s a spring.” He praises the practicality of trade not only within the economy but the social stratification as well. Most of the British gentry, he argues is at one time or another inextricably linked with the institution of trade, either through personal experience, marriage or genealogy. Oftentimes younger members of noble families entered into trade. Marriage to a tradesman’s daughter by a nobleman was also common. Overall Defoe demonstrated a high respect for tradesmen, being one himself. Not only does Defoe elevate individual British tradesmen to the level of gentleman, but he praises the entirety of British trade as a superior system. Trade, Defoe argues is a much better catalyst for social and economic change than war. He states that through imperialism and trade expansion the British empire is able to “increase commerce at home” through job creation and increased consumption. He states that increased consumption, by laws of supply and demand, increases production and in turn raises wages for the poor therefore lifting part of British society further out of poverty. Novels Robinson Crusoe Published in his late fifties, this novel relates the story of a man’s shipwreck on a desert island for twenty-eight years and his subsequent adventures. Throughout its episodic narrative, Crusoe’s struggles with faith are apparent as he bargains with God in times of life-threatening crises, but time and again he turns his back after his deliverances. He is finally content with his lot in life, separated from society, following a more genuine conversion experience. Usually read as fiction, a coincidence of background geography suggests that this may be non-fiction. In the opening pages of The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, the author describes how Crusoe settled in Bedford, married and produced a family, and that when his wife died, he went off on these further adventures. Bedford is also the place where the brother of “H. F.” in A Journal of the Plague Year retired to avoid the danger of the plague, so that by implication, if these works were not fiction, Defoe’s family met Crusoe in Bedford, from whence the information in these books was gathered. Defoe went to school in Stoke Newington, London, with a friend named Caruso. The novel has been assumed to be based in part on the story of the Scottish castaway Alexander Selkirk, who spent four years stranded in the Juan Fernández Islands, but this experience is inconsistent with the details of the narrative. The island Selkirk lived on was named Más a Tierra (Closer to Land) at the time and was renamed Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966. It has been supposed that Defoe may have also been inspired by the Latin or English translation of a book by the Andalusian-Arab Muslim polymath Ibn Tufail, who was known as “Abubacer” in Europe. The Latin edition of the book was entitled Philosophus Autodidactus and it was an earlier novel that is also set on a deserted island. Captain Singleton Defoe’s next novel was Captain Singleton (1720), an adventure story whose first half covers a traversal of Africa and whose second half taps into the contemporary fascination with piracy. It has been commended for its sensitive depiction of the close relationship between the hero and his religious mentor, Quaker William Walters. Memoirs of a Cavalier Memoirs of a Cavalier (1720) is set during the Thirty Years’ War and the English Civil War. A Journal of the Plague Year A novel often read as non-fiction, this is an account of the Great Plague of London in 1665. It is undersigned by the initials “H. F.”, suggesting the author’s uncle Henry Foe as its primary source. It is an historical account of the events based on extensive research, published in 1722. Bring out your dead! The ceaseless chant of doom echoed through a city of emptied streets and filled grave pits. For this was London in the year of 1665, the Year of the Great Plague … In 1721, when the Black Death again threatened the European Continent, Daniel Defoe wrote “A Journal of the Plague Year” to alert an indifferent populace to the horror that was almost upon them. Through the eyes of a saddler who had chosen to remain while multitudes fled, the master realist vividly depicted a plague-stricken city. He re-enacted the terror of a helpless people caught in a tragedy they could not comprehend: the weak preying on the dying, the strong administering to the sick, the sinful orgies of the cynical, the quiet faith of the pious. With dramatic insight he captured for all time the death throes of a great city.—Back cover of the New American Library version of “A Journal of the Plague Year”; Signet Classic, 1960 Colonel Jack Colonel Jack (1722) follows an orphaned boy from a life of poverty and crime to colonial prosperity, military and marital imbroglios, and religious conversion, driven by a problematic notion of becoming a “gentleman.” Moll Flanders Also in 1722, Defoe wrote Moll Flanders, another first-person picaresque novel of the fall and eventual redemption, both material and spiritual, of a lone woman in 17th-century England. The titular heroine appears as a whore, bigamist, and thief, lives in The Mint, commits adultery and incest, and yet manages to retain the reader’s sympathy. Her savvy manipulation of both men and wealth earns her a life of trials but ultimately an ending in reward. Although Moll struggles with the morality of some of her actions and decisions, religion seems to be far from her concerns throughout most of her story. However, like Robinson Crusoe, she finally repents. Moll Flanders is an important work in the development of the novel, as it challenged the common perception of femininity and gender roles in 18th-century British society, and it has come to be widely regarded as an example of erotica. Roxana Moll Flanders and Defoe’s final novel, Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress (1724), are examples of the remarkable way in which Defoe seems to inhabit his fictional characters (yet “drawn from life”), not least in that they are women. Roxana narrates the moral and spiritual decline of a high society courtesan. Roxana differs from other Defoe works because the main character does not exhibit a conversion experience, even though she claims to be a penitent later in her life, at the time that she’s relaying her story. Death Daniel Defoe died on 24 April 1731, probably while in hiding from his creditors. He often was in debtors’ prison. The cause of his death was labelled as lethargy, but he probably experienced a stroke. He was interred in Bunhill Fields (today Bunhill Fields Burial and Gardens), Borough of Islington, London, where a monument was erected to his memory in 1870.Defoe is known to have used at least 198 pen names. Selected works Novels * The Consolidator, or Memoirs of Sundry Transactions from the World in the Moon: Translated from the Lunar Language (1705) * Robinson Crusoe (1719) – originally published in two volumes:The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner: Who Lived Eight and Twenty Years [...] * The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: Being the Second and Last Part of His Life [...] * Serious Reflections During the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: With his Vision of the Angelick World (1720) * Captain Singleton (1720) * Memoirs of a Cavalier (1720) * A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) * Colonel Jack (1722) * Moll Flanders (1722) * Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress (1724) Non-fiction * An Essay Upon Projects (1697) – which includes a chapter suggesting a national insurance scheme. * The Storm (1704) – describes the worst storm ever to hit Britain in recorded times. Includes eyewitness accounts. * Atlantis Major (1711) * The Family Instructor (1715) * Memoirs of the Church of Scotland (1717) * The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard (1724) – describing Sheppard’s life of crime and concluding with the miraculous escapes from prison for which he had become a public sensation. * A Narrative of All The Robberies, Escapes, &c. of John Sheppard (1724) – written by or taken from Sheppard himself in the condemned cell before he was hanged for theft, apparently by way of conclusion to the Defoe work. * A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain, divided into circuits or journies (1724–1727) * The Political History of the Devil (1726) * The Complete English Tradesman (1726) * A treatise concerning the use and abuse of the marriage bed... (1727) * A Plan of the English Commerce (1728) Pamphlets or essays in prose * The Poor Man’s Plea (1698) * The History of the Kentish Petition (1701) * The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702) * The Great Law of Subordination Consider’d (1704) * Giving Alms No Charity, and Employing the Poor (1704) * An Appeal to Honour and Justice, Tho’ it be of his Worst Enemies, by Daniel Defoe, Being a True Account of His Conduct in Publick Affairs (1715) * A Vindication of the Press: Or, An Essay on the Usefulness of Writing, on Criticism, and the Qualification of Authors (1718) * Every-body’s Business, Is No-body’s Business (1725) * The Protestant Monastery (1726) * Parochial Tyranny (1727) * Augusta Triumphans (1728) * Second Thoughts are Best (1729) * An Essay Upon Literature (1726) * Mere Nature Delineated (1726) * Conjugal Lewdness (1727) Pamphlets or essays in verse * The True-Born Englishman: A Satyr (1701) * Hymn to the Pillory (1703) * An Essay on the Late Storm (1704) Some contested works attributed to Defoe * A Friendly Epistle by way of reproof from one of the people called Quakers, to T. B., a dealer in many words (1715). * The King of Pirates (1719) – purporting to be an account of the pirate Henry Avery. * The Pirate Gow (1725) – an account of John Gow. * A General History of the Pyrates (1724, 1725, 1726, 1828) – published in two volumes by Charles Rivington, who had a shop near St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. Published under the name of Captain Charles Johnson, it sold in many editions. * Captain Carleton’s Memoirs of an English Officer (1728). * The life and adventures of Mrs. Christian Davies, commonly call’d Mother Ross (1740) – published anonymously; printed and sold by R. Montagu in London; and attributed to Defoe but more recently not accepted. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Defoe