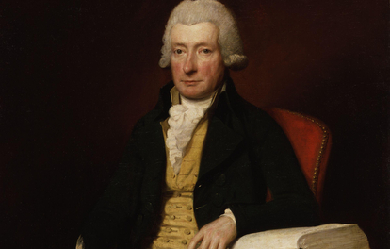

William Cowper (26 November 1731– 25 April 1800) was an English poet and hymnodist. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. In many ways, he was one of the forerunners of Romantic poetry. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called him “the best modern poet”, whilst William Wordsworth particularly admired his poem Yardley-Oak. He was a nephew of the poet Judith Madan.

Khalil Gibran (Arabic pronunciation: [xaˈliːl ʒiˈbrɑːn]) (January 6, 1883 - April 10, 1931); born Gubran Khalil Gubran, was a Lebanese-American artist, poet, and writer. Born in the town of Bsharri in modern-day Lebanon (then part of the Ottoman Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate), as a young man he emigrated with his family to the United States where he studied art and began his literary career. In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a literary and political rebel. His Romantic style was at the heart of a renaissance in modern Arabic literature, especially prose poetry, breaking away from the classical school. In Lebanon, he is still celebrated as a literary hero. He is chiefly known in the English-speaking world for his 1923 book The Prophet, an early example of inspirational fiction including a series of philosophical essays written in poetic English prose. The book sold well despite a cool critical reception, gaining popularity in the 1930s and again especially in the 1960s counterculture. Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu. In academic contexts his name is often spelled Jubrān Khalīl Jubrān,:217:255 Jibrān Khalīl Jibrān,:217:559 or Jibrān Xalīl Jibrān;:189 Arabic جبران خليل جبران , January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931) also known as Kahlil Gibran, In Lebanon Gibran was born to a Maronite Catholic family from the historical town of Bsharri in northern Lebanon. His mother Kamila, daughter of a priest, was thirty when he was born; his father Khalil was her third husband. As a result of his family's poverty, Gibran received no formal schooling during his youth. However, priests visited him regularly and taught him about the Bible, as well as the Arabic and Syriac languages. Gibran's father initially worked in an apothecary but, with gambling debts he was unable to pay, he went to work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator. Around 1891, extensive complaints by angry subjects led to the administrator being removed and his staff being investigated. Gibran's father was imprisoned for embezzlement, and his family's property was confiscated by the authorities. Kamila Gibran decided to follow her brother to the United States. Although Gibran's father was released in 1894, Kamila remained resolved and left for New York on June 25, 1895, taking Khalil, his younger sisters Mariana and Sultana, and his elder half-brother Peter (in Arabic, Butrus). In the United States The Gibrans settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second largest Syrian/Lebanese-American community in the United States. Due to a mistake at school, he was registered as Kahlil Gibran. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door to door. Gibran started school on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at a nearby settlement house. Through his teachers there, he was introduced to the avant-garde Boston artist, photographer, and publisher Fred Holland Day, who encouraged and supported Gibran in his creative endeavors. A publisher used some of Gibran's drawings for book covers in 1898. Gibran's mother, along with his elder brother Peter, wanted him to absorb more of his own heritage rather than just the Western aesthetic culture he was attracted to, so at the age of fifteen, Gibran returned to his homeland to study at a Maronite-run preparatory school and higher-education institute in Beirut, called Al-Hikma (The Wisdom). He started a student literary magazine with a classmate and was elected "college poet". He stayed there for several years before returning to Boston in 1902, coming through Ellis Island (a second time) on May 10. Two weeks before he got back, his sister Sultana died of tuberculosis at the age of 14. The next year, Peter died of the same disease and his mother died of cancer. His sister Marianna supported Gibran and herself by working at a dressmaker’s shop. Art and poetry Gibran held his first art exhibition of his drawings in 1904 in Boston, at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Elizabeth Haskell, a respected headmistress ten years his senior. The two formed an important friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran’s life. Though publicly discreet, their correspondence reveals that the two were lovers. In fact, Gibran twice proposed to her but marriage was not possible in the face of her family's conservatism. Haskell influenced not only Gibran’s personal life, but also his career. She became his editor, and introduced him to Charlotte Teller, a journalist,and Emilie Michel (Micheline), a French teacher, who accepted to pose for him as a model and became close friends. In 1908, Gibran went to study art in Paris for two years. While there he met his art study partner and lifelong friend Youssef Howayek. While most of Gibran's early writings were in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. His first book for the publishing company Alfred A. Knopf, in 1918, was The Madman, a slim volume of aphorisms and parables written in biblical cadence somewhere between poetry and prose. Gibran also took part in the New York Pen League, also known as the "immigrant poets" (al-mahjar), alongside important Lebanese-American authors such as Ameen Rihani, Elia Abu Madi and Mikhail Naimy, a close friend and distinguished master of Arabic literature, whose descendants Gibran declared to be his own children, and whose nephew, Samir, is a godson of Gibran's. Much of Gibran's writings deal with Christianity, especially on the topic of spiritual love. But his mysticism is a convergence of several different influences : Christianity, Islam, Sufism, Hinduism and theosophy. He wrote : "You are my brother and I love you. I love you when you prostrate yourself in your mosque, and kneel in your church and pray in your synagogue. You and I are sons of one faith - the Spirit." Juliet Thompson, one of Gibran's acquaintances, reported several anecdotes relating to Gibran: She recalls Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá, the leader of the Bahá’í Faith at the time of his visit to the United States, circa 1911–1912. Barbara Young, in "This Man from Lebanon: A Study of Khalil Gibran", records Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting `Abdu'l-Bahá who sat for a pair of portraits. Thompson reports Gibran saying that all the way through writing of "Jesus, The Son of Man", he thought of `Abdu'l-Bahá. Years later, after the death of `Abdu'l-Bahá, there was a viewing of the movie recording of `Abdu'l-Bahá – Gibran rose to talk and in tears, proclaimed an exalted station of `Abdu'l-Bahá and left the event weeping. His poetry is notable for its use of formal language, as well as insights on topics of life using spiritual terms. Gibran's best-known work is The Prophet, a book composed of twenty-six poetic essays. Its popularity grew markedly during the 1960s with the American counterculture and then with the flowering of the New Age movements. It has remained popular with these and with the wider population to this day. Since it was first published in 1923, The Prophet has never been out of print. Having been translated into more than forty languages, it was one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century in the United States. One of his most notable lines of poetry is from "Sand and Foam" (1926), which reads: "Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you". This line was used by John Lennon and placed, though in a slightly altered form, into the song "Julia" from The Beatles' 1968 album The Beatles (a.k.a. "The White Album”). Drawing and painting Gibran was an accomplished artist, especially in drawing and watercolour, having attended art school in Paris from 1908 to 1910, pursuing a symbolist and romantic style over then up-and-coming realism. His more than 700 images include portraits of his friends WB Yeats, Carl Jung and August Rodin. A possible Gibran painting was the subject of a June 2012 episode of the PBS TV series History Detectives. Political thought Gibran was by no means a politician. He used to say : "I am not a politician, nor do I wish to become one" and "Spare me the political events and power struggles, as the whole earth is my homeland and all men are my fellow countrymen". Nevertheless, Gibran called for the adoption of Arabic as a national language of Syria, considered from a geographic point of view, not as a political entity. When Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá in 1911–12, who traveled to the United States partly to promote peace, Gibran admired the teachings on peace but argued that "young nations like his own" be freed from Ottoman control. Gibran also wrote the famous "Pity The Nation" poem during these years, posthumously published in The Garden of the Prophet. When the Ottomans were finally driven out of Syria during World War I, Gibran's exhilaration was manifested in a sketch called "Free Syria" which appeared on the front page of al-Sa'ih's special "victory" edition. Moreover, in a draft of a play, still kept among his papers, Gibran expressed great hope for national independence and progress. This play, according to Khalil Hawi, "defines Gibran's belief in Syrian nationalism with great clarity, distinguishing it from both Lebanese and Arab nationalism, and showing us that nationalism lived in his mind, even at this late stage, side by side with internationalism.” Death and legacy Gibran died in New York City on April 10, 1931: the cause was determined to be cirrhosis of the liver and tuberculosis. Before his death, Gibran expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. This wish was fulfilled in 1932, when Mary Haskell and his sister Mariana purchased the Mar Sarkis Monastery in Lebanon, which has since become the Gibran Museum. The words written next to Gibran's grave are "a word I want to see written on my grave: I am alive like you, and I am standing beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you ...." Gibran willed the contents of his studio to Mary Haskell. There she discovered her letters to him spanning twenty-three years. She initially agreed to burn them because of their intimacy, but recognizing their historical value she saved them. She gave them, along with his letters to her which she had also saved, to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library before she died in 1964. Excerpts of the over six hundred letters were published in "Beloved Prophet" in 1972. Mary Haskell Minis (she wed Jacob Florance Minis in 1923) donated her personal collection of nearly one hundred original works of art by Gibran to the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia in 1950. Haskell had been thinking of placing her collection at the Telfair as early as 1914. In a letter to Gibran, she wrote "I am thinking of other museums ... the unique little Telfair Gallery in Savannah, Ga., that Gari Melchers chooses pictures for. There when I was a visiting child, form burst upon my astonished little soul." Haskell's gift to the Telfair is the largest public collection of Gibran’s visual art in the country, consisting of five oils and numerous works on paper rendered in the artist’s lyrical style, which reflects the influence of symbolism. The future American royalties to his books were willed to his hometown of Bsharri, to be "used for good causes”. Works In Arabic: * Nubthah fi Fan Al-Musiqa (Music, 1905) * Ara'is al-Muruj (Nymphs of the Valley, also translated as Spirit Brides and Brides of the Prairie, 1906) * al-Arwah al-Mutamarrida (Rebellious Spirits, 1908) * al-Ajniha al-Mutakassira (Broken Wings, 1912) * Dam'a wa Ibtisama (A Tear and A Smile, 1914) * al-Mawakib (The Processions, 1919) * al-‘Awāsif (The Tempests, 1920) * al-Bada'i' waal-Tara'if (The New and the Marvellous, 1923) In English, prior to his death: * The Madman (1918) (downloadable free version) * Twenty Drawings (1919) * The Forerunner (1920) * The Prophet, (1923) * Sand and Foam (1926) * Kingdom of the Imagination (1927) * Jesus, The Son of Man (1928) * The Earth Gods (1931) Posthumous, in English: * The Wanderer (1932) * The Garden of the Prophet (1933, Completed by Barbara Young) * Lazarus and his Beloved (Play, 1933) Collections: * Prose Poems (1934) * Secrets of the Heart (1947) * A Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1951) * A Self-Portrait (1959) * Thoughts and Meditations (1960) * A Second Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1962) * Spiritual Sayings (1962) * Voice of the Master (1963) * Mirrors of the Soul (1965) * Between Night & Morn (1972) * A Third Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1975) * The Storm (1994) * The Beloved (1994) * The Vision (1994) * Eye of the Prophet (1995) * The Treasured Writings of Kahlil Gibran (1995) Other: * Beloved Prophet, The love letters of Khalil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and her private journal (1972, edited by Virginia Hilu) Memorials and honors * Lebanese Ministry of Post and Telecommunications published a stamp in his honor in 1971. * Gibran Museum in Bsharri, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden, Beirut, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran collectin, Soumaya Museum, Mexico. * Kahlil Gibran Street, Ville Saint-Laurent, Quebec, Canada inaugurated on 27 Sept. 2008 on occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth. * Gibran Kahlil Gibran Skiing Piste, The Cedars Ski Resort, Lebanon * Kahlil Gibran Memorial Garden in Washington, D.C., dedicated in 1990 * The Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace, University of Maryland, currently held by Suheil Bushrui * Pavilion K. Gibran at École Pasteur in Montréal, Quebec, Canada * Gibran Memorial Plaque in Copley Square, Boston, Massachusetts see Kahlil Gibran (sculptor). * Khalil Gibran International Academy, a public high school in Brooklyn, NY, opened in September 2007 * Khalil Gibran Park (Parcul Khalil Gibran) in Bucharest, Romania * Gibran Kalil Gibran sculpture on a marble pedestal indoors at Arab Memorial building at Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil * Gibran Khalil Gibran Memorial, in front of Plaza de las Naciones. Buenos Aires. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khalil_Gibran

Rare & Strange...Lover of Wine, Sports, Skulls, The Sun, All Things Fast, Giving & Taking Chances, People Watching, Music, Poetry, Animals, Dialogue, Sensuality, Sexuality, Passion & Passionate People, Confidence, Art, Movies, Conversations, Romance, Philosophy & Johnny Depp.....Watching movies that make you think - like A waking life or with great dialogue. It's all about the lighting... What makes us different, you & I? I'm on my life mission of seeking the strange, yet the similar, the one who will make me think, make me not think, who will drive me wild with words, passion and love. I wear my heart on my sleeve and won't stop to let the world take away my spirit. I refuse to settle even if it means I never stop ...but I know he's out there my eclectic twin soul who will love adventure, random rants, giving and caring for others, fitting in between the cracks with me and standing out in the crowd too. Intelligent and Cultured , both city and country lover, who will pack up run through the mountains taking random photos of cemeteries and visions in the clouds, who will jump on a horse and ride a wild ride with me...a best friend, a soul mate, the other half who inspires me and I inspire he and long talks with large glasses of wine and endless nights in electric passion ...tantric, twisted, non-judging just accepting each other completely, swallowing each other ...

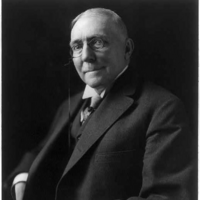

James Whitcomb Riley (October 7, 1849 – July 22, 1916) was an American writer, poet, and best-selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the "Hoosier Poet" and "Children's Poet" for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man". Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and created a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform. He became more popular in spite of the bad press he received, and as a result extricated himself from poorly negotiated contracts that limited his earnings; he quickly became very wealthy. Riley became a bestselling author in the 1890s. His children's poems were compiled into a book and illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy. Titled the Rhymes of Childhood, the book was his most popular and sold millions of copies. As a poet, Riley achieved an uncommon level of fame during his own lifetime. He was honored with annual Riley Day celebrations around the United States and was regularly called on to perform readings at national civic events. He continued to write and hold occasional poetry readings until a stroke paralyzed his right arm in 1910. Riley's chief legacy was his influence in fostering the creation of a midwestern cultural identity and his contributions to the Golden Age of Indiana Literature. Along with other writers of his era, he helped create a caricature of midwesterners and formed a literary community that produced works rivaling the established eastern literati. There are many memorials dedicated to Riley, including the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children. Family and background James Whitcomb Riley was born on October 7, 1849, in the town of Greenfield, Indiana, the third of the six children of Reuben Andrew and Elizabeth Marine Riley.[n 1] Riley's father was an attorney, and in the year before Riley's birth, he was elected a member of the Indiana House of Representatives as a Democrat. He developed a friendship with James Whitcomb, the governor of Indiana, after whom he named his son. Martin Riley, Riley's uncle, was an amateur poet who occasionally wrote verses for local newspapers. Riley was fond of his uncle who helped influence his early interest in poetry. Shortly after Riley's birth, the family moved into a larger house in town. Riley was "a quiet boy, not talkative, who would often go about with one eye shut as he observed and speculated." His mother taught him to read and write at home before sending him to the local community school in 1852. He found school difficult and was frequently in trouble. Often punished, he had nothing kind to say of his teachers in his writings. His poem "The Educator" told of an intelligent but sinister teacher and may have been based on one of his instructors. Riley was most fond of his last teacher, Lee O. Harris. Harris noticed Riley's interest in poetry and reading and encouraged him to pursue it further. Riley's school attendance was sporadic, and he graduated from grade eight at age twenty in 1869. In an 1892 newspaper article, Riley confessed that he knew little of mathematics, geography, or science, and his understanding of proper grammar was poor. Later critics, like Henry Beers, pointed to his poor education as the reason for his success in writing; his prose was written in the language of common people which spurred his popularity. Childhood influences Riley lived in his parents' home until he was twenty-one years old. At five years old he began spending time at the Brandywine Creek just outside Greenfield. His poems "The Barefoot Boy" and "The Old Swimmin' Hole" referred back to his time at the creek. He was introduced in his childhood to many people who later influenced his poetry. His father regularly brought home a variety of clients and disadvantaged people to give them assistance. Riley's poem "The Raggedy Man" was based on a German tramp his father hired to work at the family home. Riley picked up the cadence and character of the dialect of central Indiana from travelers along the old National Road. Their speech greatly influenced the hundreds of poems he wrote in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect. Riley's mother frequently told him stories of fairies, trolls, and giants, and read him children's poems. She was very superstitious, and influenced Riley with many of her beliefs. They both placed "spirit rappings" in their homes on places like tables and bureaus to capture any spirits that may have been wandering about. This influence is recognized in many of his works, including "Flying Islands of the Night." As was common at that time, Riley and his friends had few toys and they amused themselves with activities. With his mother's aid, Riley began creating plays and theatricals which he and his friends would practice and perform in the back of a local grocery store. As he grew older, the boys named their troupe the Adelphians and began to have their shows in barns where they could fit larger audiences. Riley wrote of these early performances in his poem "When We First Played 'Show'," where he referred to himself as "Jamesy." Many of Riley's poems are filled with musical references. Riley had no musical education, and could not read sheet music, but learned from his father how to play guitar, and from a friend how to play violin. He performed in two different local bands, and became so proficient on the violin he was invited to play with a group of adult Freemasons at several events. A few of his later poems were set to music and song, one of the most well known being A Short'nin' Bread Song—Pieced Out. When Riley was ten years old, the first library opened in his hometown. From an early age he developed a love of literature. He and his friends spent time at the library where the librarian read stories and poems to them. Charles Dickens became one Riley's favorites, and helped inspire the poems "St. Lirriper," "Christmas Season," and "God Bless Us Every One." Riley's father enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War, leaving his wife to manage the family home. While he was away, the family took in a twelve-year-old orphan named Mary Alice "Allie" Smith. Smith was the inspiration for Riley's poem "Little Orphant Annie". Riley intended to name the poem "Little Orphant Allie", but a typesetter's error changed the name of the poem during printing. Finding poetry Riley's father returned from the war partially paralyzed. He was unable to continue working in his legal practice and the family soon fell into financial distress. The war had a negative physiological effect on him, and his relationship with his family quickly deteriorated. He opposed Riley's interest in poetry and encouraged him to find a different career. The family finances finally disintegrated and they were forced to sell their town home in April 1870 and return to their country farm. Riley's mother was able to keep peace in the family, but after her death in August from heart disease, Riley and his father had a final break. He blamed his mother's death on his father's failure to care for her in her final weeks. He continued to regret the loss of his childhood home and wrote frequently of how it was so cruelly snatched from him by the war, subsequent poverty, and his mother's death. After the events of 1870, he developed an addiction to alcohol which he struggled with for the remainder of his life. Becoming increasingly belligerent toward his father, Riley moved out of the family home and briefly had a job painting houses before leaving Greenfield in November 1870. He was recruited as a Bible salesman and began working in the nearby town of Rushville, Indiana. The job provided little income and he returned to Greenfield in March 1871 where he started an apprenticeship to a painter. He completed the study and opened a business in Greenfield creating and maintaining signs. His earliest known poems are verses he wrote as clever advertisements for his customers. Riley began participating in local theater productions with the Adelphians to earn extra income, and during the winter months, when the demand for painting declined, Riley began writing poetry which he mailed to his brother living in Indianapolis. His brother acted as his agent and offered the poems to the newspaper Indianapolis Mirror for free. His first poem was featured on March 30, 1872 under the pseudonym "Jay Whit." Riley wrote more than twenty poems to the newspaper, including one that was featured on the front page. In July 1872, after becoming convinced sales would provide more income than sign painting, he joined the McCrillus Company based in Anderson, Indiana. The company sold patent medicines that they marketed in small traveling shows around Indiana. Riley joined the act as a huckster, calling himself the "Painter Poet". He traveled with the act, composing poetry and performing at the shows. After his act he sold tonics to his audience, sometimes employing dishonesty. During one stop, Riley presented himself as a formerly blind painter who had been cured by a tonic, using himself as evidence to encourage the audience to purchase his product. Riley began sending poems to his brother again in February 1873. About the same time he and several friends began an advertisement company. The men traveled around Indiana creating large billboard-like signs on the sides of buildings and barns and in high places that would be visible from a distance. The company was financially successful, but Riley was continually drawn to poetry. In October he traveled to South Bend where he took a job at Stockford & Blowney painting verses on signs for a month; the short duration of his job may have been due to his frequent drunkenness at that time. In early 1874, Riley returned to Greenfield to become a writer full-time. In February he submitted a poem entitled "At Last" to the Danbury News, a Connecticut newspaper. The editors accepted his poem, paid him for it, and wrote him a letter encouraging him to submit more. Riley found the note and his first payment inspiring. He began submitting poems regularly to the editors, but after the newspaper shut down in 1875, Riley was left without a paying publisher. He began traveling and performing with the Adelphians around central Indiana to earn an income while he searched for a new publisher. In August 1875 he joined another traveling tonic show run by the Wizard Oil Company. Newspaper work Riley began sending correspondence to the famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during late 1875 seeking his endorsement to help him start a career as a poet. He submitted many poems to Longfellow, whom he considered to be the greatest living poet. Not receiving a prompt response, he sent similar letters to John Townsend Trowbridge, and several other prominent writers askng for an endorsement. Longfellow finally replied in a brief letter, telling Riley that "I have read [the poems] in great pleasure, and think they show a true poetic faculty and insight." Riley carried the letter with him everywhere and, hoping to receive a job offer and to create a market for his poetry, he began sending poems to dozens of newspapers touting Longfellow's endorsement. Among the newspapers to take an interest in the poems was the Indianapolis Journal, a major Republican Party metropolitan newspaper in Indiana. Among the first poems the newspaper purchased from Riley were "Song of the New Year", "An Empty Nest", and a short story entitled "A Remarkable Man". The editors of the Anderson Democrat discovered Riley's poems in the Indianapolis Journal and offered him a job as a reporter in February 1877. Riley accepted. He worked as a normal reporter gathering local news, writing articles, and assisting in setting the typecast on the printing press. He continued to write poems regularly for the newspaper and to sell other poems to larger newspapers. During the year Riley spent working in Anderson, he met and began to court Edora Mysers. The couple became engaged, but terminated the relationship after they decided against marriage in August. After a rejection of his poems by an eastern periodical, Riley began to formulate a plot to prove his work was of good quality and that it was being rejected only because his name was unknown in the east. Riley authored a poem imitating the style of Edgar Allan Poe and submitted it to the Kokomo Dispatch under a fictitious name claiming it was a long lost Poe poem. The Dispatch published the poem and reported it as such. Riley and two other men who were part of the plot waited two weeks for the poem to be published by major newspapers in Chicago, Boston, and New York to gauge their reaction; they were disappointed. While a few newspapers believed the poem to be authentic, the majority did not, claiming the quality was too poor to be authored by Poe. An employee of the Dispatch learned the truth of the incident and reported it to the Kokomo Tribune, which published an expose that outed Riley as a conspirator behind the hoax. The revelation damaged the credibility of the Dispatch and harmed Riley's reputation. In the aftermath of the Poe plot, Riley was dismissed from the Democrat, so he returned to Greenfield to spend time writing poetry. Back home, he met Clara Louise Bottsford, a school teacher boarding in his father's home. They found they had much in common, particularly their love of literature. The couple began a twelve-year intermittent relationship which would be Riley's longest lasting. In mid-1878 the couple had their first breakup, caused partly by Riley's alcohol addiction. The event led Riley to make his first attempt to give up liquor. He joined a local temperance organization, but quit after a few weeks. Performing poet Without a steady income, his financial situation began to deteriorate. He began submitting his poems to more prominent literary magazines, including Scribner's Monthly, but was informed that although he showed promise, his work was still short of the standards required for use in their publications. Locally, he was still dealing with the stigma of the Poe plot. The Indianapolis Journal and other newspapers refused to accept his poetry, leaving Riley desperate for income. In January 1878 on the advice of a friend, Riley paid an entrance fee to join a traveling lecture circuit where he could give poetry readings. In exchange, he received a portion of the profit his performances earned. Such circuits were popular at the time, and Riley quickly earned a local reputation for his entertaining readings. In August 1878, Riley followed Indiana Governor James D. Williams as speaker at a civic event in a small town near Indianapolis. He recited a recently composed poem, "A Childhood Home of Long Ago," telling of life in pioneer Indiana. The poem was well received and was given good reviews by several newspapers. "Flying Islands of the Night" is the only play that Riley wrote and published. Authored while Riley was traveling with the Adelphians, but never performed, the play has similarities to A Midsummer Night's Dream, which Riley may have used as a model. Flying Islands concerns a kingdom besieged by evil forces of a sinister queen who is defeated eventually by an angel-like heroine. Most reviews were positive. Riley published the play and it became popular in the central Indiana area during late 1878, helping Riley to convince newspapers to again accept his poetry. In November 1879 he was offered a position as a columnist at the Indianapolis Journal and accepted after being encouraged by E.B. Matindale, the paper's chief editor. Although the play and his newspaper work helped expose him to a wider audience, the chief source of his increasing popularity was his performances on the lecture circuit. He made both dramatic and comedic readings of his poetry, and by early 1879 could guarantee large crowds whenever he performed. In an 1894 article, Hamlin Garland wrote that Riley's celebrity resulted from his reading talent, saying "his vibrant individual voice, his flexible lips, his droll glance, united to make him at once poet and comedian—comedian in the sense in which makes for tears as well as for laughter." Although he was a good performer, his acts were not entirely original in style; he frequently copied practices developed by Samuel Clemens and Will Carleton. His tour in 1880 took him to every city in Indiana where he was introduced by local dignitaries and other popular figures, including Maurice Thompson with whom he began to develop a close friendship. Developing and maintaining his publicity became a constant job, and received more of his attention as his fame grew. Keeping his alcohol addiction secret, maintaining the persona of a simple rural poet and a friendly common person became most important. Riley identified these traits as the basis of his popularity during the mid-1880s, and wrote of his need to maintain a fictional persona. He encouraged the stereotype by authoring poetry he thought would help build his identity. He was aided by editorials he authored and submitted to the Indianapolis Journal offering observations on events from his perspective as a "humble rural poet". He changed his appearance to look more mainstream, and began by shaving his mustache off and abandoning the flamboyant dress he employed in his early circuit tours. By 1880 his poems were beginning to be published nationally and were receiving positive reviews. "Tom Johnson's Quit" was carried by newspapers in twenty states, thanks in part to the careful cultivation of his popularity. Riley became frustrated that despite his growing acclaim, he found it difficult to achieve financial success. In the early 1880s, in addition to his steady performing, Riley began producing many poems to increase his income. Half of his poems were written during the period. The constant labor had adverse effects on his health, which was worsened by his drinking. At the urging of Maurice Thompson, he again attempted to stop drinking liquor, but was only able to give it up for a few months. Politics In March 1888, Riley traveled to Washington, D.C. where he had dinner at the White House with other members of the International Copyright League and President of the United States Grover Cleveland. Riley made a brief performance for the dignitaries at the event before speaking about the need for international copyright protections. Cleveland was enamored by Riley's performance and invited him back for a private meeting during which the two men discussed cultural topics. In the 1888 Presidential Election campaign, Riley's acquaintance Benjamin Harrison was nominated as the Republican candidate. Although Riley had shunned politics for most of his life, he gave Harrison a personal endorsement and participated in fund-raising events and vote stumping. The election was exceptionally partisan in Indiana, and Riley found the atmosphere of the campaign stressful; he vowed never to become involved with politics again. Upon Harrison's election, he suggested Riley be named the national poet laureate, but Congress failed to act on the request. Riley was still honored by Harrison and visited him at the White House on several occasions to perform at civic events. Pay problems and scandal Riley and Nye made arrangements with James Pond to make two national tours during 1888 and 1889. The tours were popular and generally sold out, with hundreds having to be turned away. The shows were usually forty-five minutes to an hour long and featured Riley reading often humorous poetry interspersed by stories and jokes from Nye. The shows were informal and the two men adjusted their performances based on their audiences reactions. Riley memorized forty of his poems for the shows to add to his own versatility. Many prominent literary and theatrical people attended the shows. At a New York City show in March 1888, Augustin Daly was so enthralled by the show he insisted on hosting the two men at a banquet with several leading Broadway theatre actors. Despite Riley serving as the act's main draw, he was not permitted to become an equal partner in the venture. Nye and Pond both received a percentage of the net profit, while Riley was paid a flat rate for each performance. In addition, because of Riley's past agreements with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, he was required to pay half of his fee to his agent Amos Walker. This caused the other men to profit more than Riley from his own work. To remedy this situation, Riley hired his brother-in-law Henry Eitel, an Indianapolis banker, to manage his finances and act on his behalf to try and extricate him from his contract. Despite discussions and assurances from Pond that he would work to address the problem, Eitel had no success. Pond ultimately made the situation worse by booking months of solid performances, not allowing Riley and Nye a day of rest. These events affected Riley physically and emotionally; he became despondent and began his worst period of alcoholism. During November 1889, the tour was forced to cancel several shows after Riley became severely inebriated at a stop in Madison, Wisconsin. Walker began monitoring Riley and denying him access to liquor, but Riley found ways to evade Walker. At a stop at the Masonic Temple Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky, in January 1890, Riley paid the hotel's bartender to sneak whiskey to his room. He became too drunk to perform, and was unable to travel to the next stop. Nye terminated the partnership and tour in response. The reason for the breakup could not be kept secret, and hotel staff reported to the Louisville Courier-Journal that they saw Riley in a drunken stupor walking around the hotel. The story made national news and Riley feared his career was ruined. He secretly left Louisville at night and returned to Indianapolis by train. Eitel defended Riley to the press in an effort to gain sympathy for Riley, explaining the abusive financial arrangements his partners had made. Riley however refused to speak to reporters and hid himself for weeks. Much to Riley's surprise, the news reports made him more popular than ever. Many people thought the stories were exaggerated, and Riley's carefully cultivated image made it difficult for the public to believe he was an alcoholic. Riley had stopped sending poetry to newspapers and magazines in the aftermath, but they soon began corresponding with him requesting that he resume writing. This encouraged Riley, and he made another attempt to give up liquor as he returned to his public career. The negative press did not end however, as Nye and Pond threatened to sue Riley for causing their tour to end prematurely. They claimed to have lost $20,000. Walker threatened a separate suit demanding $1,000. Riley hired Indianapolis lawyer William P. Fishback to represent him and the men settled out of court. The full details of the settlement were never disclosed, but whatever the case, Riley finally extricated himself from his old contracts and became a free agent. The exorbitant amount Riley was being sued for only reinforced public opinion that Riley had been mistreated by his partners, and helped him maintain his image. Nye and Riley remained good friends, and Riley later wrote that Pond and Walker were the source of the problems. Riley's poetry had become popular in Britain, in large part due to his book Old-Fashioned Roses. In May 1891 he traveled to England to make a tour and what he considered a literary pilgrimage. He landed in Liverpool and traveled first to Dumfries, Scotland, the home and burial place of Robert Burns. Riley had long been compared to Burns by critics because they both used dialect in their poetry and drew inspiration from their rural homes. He then traveled to Edinburgh, York, and London, reciting poetry for gatherings at each stop. Augustin Daly arranged for him to give a poetry reading to prominent British actors in London. Riley was warmly welcomed by its literary and theatrical community and he toured places that Shakespeare had frequented. Riley quickly tired of traveling abroad and began longing for home, writing to his nephew that he regretted having left the United States. He curtailed his journey and returned to New York City in August. He spent the next months in his Greenfield home attempting to write an epic poem, but after several attempts gave up, believing he did not possess the ability. By 1890, Riley had authored almost all of his famous poems. The few poems he did write during the 1890s were generally less well received by the public. As a solution, Riley and his publishers began reusing poetry from other books and printing some of his earliest works. When Neighborly Poems was published in 1891, a critic working for the Chicago Tribune pointed out the use of Riley's earliest works, commenting that Riley was using his popularity to push his crude earlier works onto the public only to make money. Riley's newest poems published in the 1894 book Armazindy received very negative reviews that referred to poems like "The Little Dog-Woggy" and "Jargon-Jingle" as "drivel" and to Riley as a "worn out genius." Most of his growing number of critics suggested that he ignored the quality of the poems for the sake of making money. National poet Riley had become very wealthy by the time he ended touring in 1895, and was earning $1,000 a week. Although he retired, he continued to make minor appearances. In 1896, Riley performed four shows in Denver. Most of the performances of his later life were at civic celebrations. He was a regular speaker at Decoration Day events and delivered poetry before the unveiling of monuments in Washington, D.C. Newspapers began referring to him as the "National Poet", "the poet laureate of America", and "the people's poet laureate". Riley wrote many of his patriotic poems for such events, including "The Soldier", "The Name of Old Glory", and his most famous such poem, "America!". The 1902 poem "America, Messiah of Nations" was written and read by Riley for the dedication of the Indianapolis Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. The only new poetry Riley published after the end of the century were elegies for famous friends. The poetic qualities of the poems were often poor, but they contained many popular sentiments concerning the deceased. Among those he eulogized were Benjamin Harrison, Lew Wallace, and Henry Lawton. Because of the poor quality of the poems, his friends and publishers requested that he stop writing them, but he refused. In 1897, Riley's publishers suggested that he create a multi-volume series of books containing his complete life works. With the help of his nephew, Riley began working to compile the books, which eventually totaled sixteen volumes and were finally completed in 1914. Such works were uncommon during the lives of writers, attesting to the uncommon popularity Riley had achieved. His works had become staples for Ivy League literature courses and universities began offering him honorary degrees. The first was Yale in 1902, followed by a Doctorate of Letters from the University of Pennsylvania in 1904. Wabash College and Indiana University granted him similar awards. In 1908 he was elected member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1912 they conferred upon him a special medal for poetry. Riley was influential in helping other poets start their careers, having particularly strong influences on Hamlin Garland, William Allen White, and Edgar Lee Masters. He discovered aspiring African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1892. Riley thought Dunbar's work was "worthy of applause", and wrote him letters of recommendation to help him get his work published. Declining health In 1901, Riley's doctor diagnosed him with neurasthenia, a nervous disorder, and recommended long periods of rest as a cure.[173] Riley remained ill for the rest of his life and relied on his landlords and family to aid in his care. During the winter months he moved to Miami, Florida, and during summer spent time with his family in Greenfield. He made only a few trips during the decade, including one to Mexico in 1906. He became very depressed by his condition, writing to his friends that he thought he could die at any moment, and often used alcohol for relief.[174] In March 1909, Riley was stricken a second time with Bell's palsy, and partial deafness, the symptoms only gradually eased over the course of the year.[175] Riley was a difficult patient, and generally refused to take any medicine except the patent medicines he had sold in his earlier years; the medicines often worsened his conditions, but his doctors could not sway his opinion.[176] On July 10, 1910 he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping for a quick recovery, his family kept the news from the press until September. Riley found the loss of use of his writing hand the worst part of the stroke, which served only to further depress him.[174][177] With his health so poor, he decided to work on a legacy by which to be remembered in Indianapolis. In 1911 he donated land and funds to build a new library on Pennsylvania Avenue.[178] By 1913, with the aid of a cane, Riley began to recover his ability to walk. His inability to write, however, nearly ended his production of poems. George Ade worked with him from 1910 through 1916 to write his last five poems and several short autobiographical sketches as Riley dictated. His publisher continued recycling old works into new books, which remained in high demand.[178] Since the mid-1880s, Riley had been the nation's most read poet, a trend that accelerated at the turn of the century. In 1912 Riley recorded readings of his most popular poetry to be sold by Victor Records. Riley was the subject of three paintings by T. C. Steele. The Indianapolis Arts Association commissioned a portrait of Riley to be created by world famous painter John Singer Sargent. Riley's image became a nationally known icon and many businesses capitalized on his popularity to sell their products; Hoosier Poet brand vegetables became a major trade-name in the midwest.[179] In 1912, the governor of Indiana instituted Riley Day on the poet's birthday. Schools were required to teach Riley's poems to their children, and banquet events were held in his honor around the state. In 1915 and 1916 the celebration was national after being proclaimed in most states. The annual celebration continued in Indiana until 1968.[180] In early 1916 Riley was filmed as part of a movie to celebrate Indiana's centennial, the video is on display at the Indiana State Library.[181][182] Death and legacy On July 22, 1916, Riley suffered a second stroke. He recovered enough during the day to speak and joke with his companions. He died before dawn the next morning, July 23.[183] Riley's death shocked the nation and made front page headlines in major newspapers.[184] President Woodrow Wilson wrote a brief note to Riley's family offering condolences on behalf the entire nation. Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston offered to allow Riley to lie in state at the Indiana Statehouse—Abraham Lincoln being the only other person to have previously received such an honor.[185] During the ten hours he lay in state on July 24, more than thirty-five thousand people filed past his bronze casket; the line was still miles long at the end of the day and thousands were turned away. The next day a private funeral ceremony was held and attended by many dignitaries. A large funeral procession then carried him to Crown Hill Cemetery where he was buried in a tomb at the top of the hill, the highest point in the city of Indianapolis.[186] Within a year of Riley's death many memorials were created, including several by the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association. The James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children was created and named in his honor by a group of wealthy benefactors and opened in 1924. In the following years, other memorials intended to benefit children were created, including Camp Riley for youth with disabilities.[187][188] The memorial foundation purchased the poet's Lockerbie home in Indianapolis and it is now maintained as a museum. The James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home is the only late-Victorian home in Indiana that is open to the public and the United States' only late-Victorian preservation, featuring authentic furniture and decor from that era. His birthplace and boyhood home, now the James Whitcomb Riley House, is preserved as a historical site.[189] A Liberty ship, commissioned April 23, 1942, was christened the SS James Whitcomb Riley. It served with the United States Maritime Commission until being scrapped in 1971. James Whitcomb Riley High School opened in South Bend, Indiana in 1924. In 1950, there was a James Whitcomb Riley Elementary School in Hammond, Indiana, but it was torn down in 2006. East Chicago, Indiana had a Riley School at one time, as did neighboring Gary, Indiana and Anderson, Indiana. One of New Castle, Indiana's elementary schools is named for Riley as is the road on which it is located. The former Greenfield High School was converted to Riley Elementary School and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 10-cent stamp honoring Riley.[190] As a lasting tribute, the citizens of Greenfield hold a festival every year in Riley's honor. Taking place the first or second weekend of October, the "Riley Days" festival traditionally commences with a flower parade in which local school children place flowers around Myra Reynolds Richards' statue of Riley on the county courthouse lawn, while a band plays lively music in honor of the poet. Weeks before the festival, the festival board has a queen contest. The 2010–2011 queen was Corinne Butler. The pageant has been going on many years in honor of the Hoosier poet[191] According to historian Elizabeth Van Allen, Riley was instrumental in helping form a midwestern cultural identity. The midwestern United States had no significant literary community before the 1880s.[192] The works of the Western Association of Writers, most notably those of Riley and Wallace, helped create the midwest's cultural identity and create a rival literary community to the established eastern literari. For this reason, and the publicity Riley's work created, he was commonly known as the "Hoosier Poet." Critical reception and style Riley was among the most popular writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, known for his "uncomplicated, sentimental, and humorous" writing.[195] Often writing his verses in dialect, his poetry caused readers to recall a nostalgic and simpler time in earlier American history. This gave his poetry a unique appeal during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the United States. Riley was a prolific writer who "achieved mass appeal partly due to his canny sense of marketing and publicity."[195] He published more than fifty books, mostly of poetry and humorous short stories, and sold millions of copies.[195] Riley is often remembered for his most famous poems, including the "The Raggedy Man" and "Little Orphant Annie". Many of his poems, including those, where partially autobiographical, as he used events and people from his childhood as an inspiration for subject matter.[195] His poems often contained morals and warnings for children, containing messages telling children to care for the less fortunate of society. David Galens and Van Allen both see these messages as Riley's subtle response to the turbulent economic times of the Gilded Age and the growing progressive movement.[196] Riley believed that urbanization robbed children of their innocence and sincerity, and in his poems he attempted to introduce and idolize characters who had not lost those qualities.[197] His children's poems are "exuberant, performative, and often display Riley's penchant for using humorous characterization, repetition, and dialect to make his poetry accessible to a wide-ranging audience."[195][198] Although hinted at indirectly in some poems, Riley wrote very little on serious subject matter, and actually mocked attempts at serious poetry. Only a few of his sentimental poems concerned serious subjects. "Little Mandy's Christmas-Tree", "The Absence of Little Wesley", and "The Happy Little Cripple" were about poverty, the death of a child, and disabilities. Like his children's poems, they too contained morals, suggesting society should pity the downtrodden and be charitable.[195][198] Riley wrote gentle and romantic poems that were not in dialect. They generally consisted of sonnets and were strongly influenced by the works of John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His standard English poetry was never as popular as his Hoosier dialect poems.[195] Still less popular were the poems Riley authored in his later years; most were to commemorate important events of American history and to eulogize the dead.[195] Riley's contemporaries acclaimed him "America's best-loved poet".[195][198] In 1920, Henry Beers lauded the works of Riley "as natural and unaffected, with none of the discontent and deep thought of cultured song."[195] Samuel Clemens, William Dean Howells, and Hamlin Garland, each praised Riley's work and the idealism he expressed in his poetry. Only a few critics of the period found fault with Riley's works. Ambrose Bierce criticized Riley for his frequent use of dialect. Bierce accused Riley of using dialect to "cover up [the] faulty construction" of his poems.[195] Edgar Lee Masters found Riley's work to be superficial, claiming it lacked irony and that he had only a "narrow emotional range".[195] By the 1930s popular critical opinion towards Riley's works began to shift in favor of the negative reviews. In 1951, James T. Farrell said Riley's works were "cliched." Galens wrote that modern critics consider Riley to be a "minor poet, whose work—provincial, sentimental, and superficial though it may have been—nevertheless struck a chord with a mass audience in a time of enormous cultural change."[195] Thomas C. Johnson wrote that what most interests modern critics was Riley's ability to market his work, saying he had a unique understanding of "how to commodify his own image and the nostalgic dreams of an anxious nation."[195] Among the earliest widespread criticisms of Riley were opinions that his dialect writing did not actually represent the true dialect of central Indiana. In 1970 Peter Revell wrote that Riley's dialect was more similar to the poor speech of a child rather than the dialect of his region. Revell made extensive comparison to historical texts and Riley's dialect usage. Philip Greasley wrote that that while "some critics have dismissed him as sub-literary, insincere, and an artificial entertainer, his defenders reply that an author so popular with millions of people in different walks of life must contribute something of value, and that his faults, if any, can be ignored." References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Whitcomb_Riley

I am an enthusiastic scholar of American, Irish, and English history, Victorian literature, myths, legends, folklore, and Pagan religions. My prose and poetry are generally Gothic in theme and usually set in historical periods. My favourite authors are Edgar Allen Poe, Samuel Clemens, Charles Dickens, Henry James, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H.P. Lovecraft, M. R. James, Washington Irving, and Oscar Wilde, just to name a few, and my favourite poets are Keats, Byron, Yeats, Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Longfellow. I have three books of poetry currently on the market, three Gothic novels, one anthology of six horror stories, and several novellas and novelettes. I was raised in Wheatridge, Colorado and attended The University of Colorado at Denver. I currently live in Corvallis, Montana in the great Pacific Northwest.

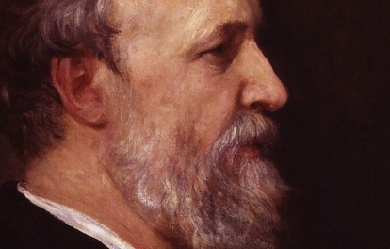

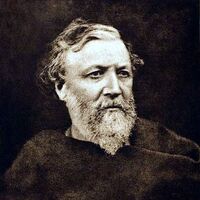

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father, who worked as a bank clerk, was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning's education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was fourteen. From fourteen to sixteen he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship.

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's view, were responsible for a vainglorious war. He later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston Trilogy". Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the British Army just as the threat of World War I was realised, and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry on the day the United Kingdom declared war (4 August 1914). He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing.

These are writings from the inner workings of a mind in constant thought about LIFE and everything it entails for the purpose of self-transcendence and with the intention to bring more understanding and healing to my own life and possibly those of others. My journey is one of self-exploration and discovery. Since my beliefs lie on the premise that we are so strongly connected to everything in existence, in getting to know myself I am getting to know the world. Learning about the world teaches me about myself. I find freedom in understanding and expression. My one true love is the paradox of questioning existence.

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that “the negro was in vogue” which was later paraphrased as “when Harlem was in vogue”.