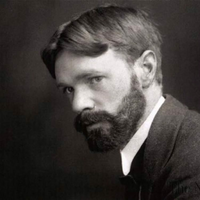

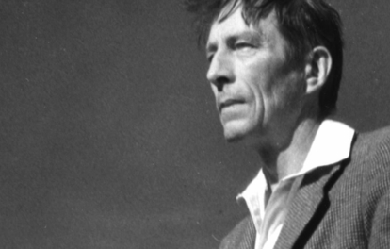

David Herbert Richards Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter who published as D. H. Lawrence. His collected works represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. In them, Lawrence confronts issues relating to emotional health and vitality, spontaneity, and instinct. Lawrence’s opinions earned him many enemies and he endured official persecution, censorship, and misrepresentation of his creative work throughout the second half of his life, much of which he spent in a voluntary exile which he called his “savage pilgrimage”. At the time of his death, his public reputation was that of a pornographer who had wasted his considerable talents. E. M. Forster, in an obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as, “The greatest imaginative novelist of our generation”. Later, the influential Cambridge critic F. R. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness, placing much of Lawrence's fiction within the canonical “great tradition” of the English novel. Lawrence is now valued by many as a visionary thinker and significant representative of modernism in English literature.

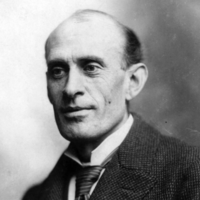

Edgar Lee Masters (August 23, 1868– March 5, 1950) was an American attorney, poet, biographer, and dramatist. He is the author of Spoon River Anthology, The New Star Chamber and Other Essays, Songs and Satires, The Great Valley, The Serpent in the Wilderness An Obscure Tale, The Spleen, Mark Twain: A Portrait, Lincoln: The Man, and Illinois Poems. In all, Masters published twelve plays, twenty-one books of poetry, six novels and six biographies, including those of Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain, Vachel Lindsay, and Walt Whitman. Life and career Born in Garnett, Kansas to attorney Hardin Wallace Masters and Emma J. Dexter, his father had briefly moved to set up a law practice, then soon moved back to his paternal grandparents’ farm near Petersburg in Menard County, Illinois. In 1880 they moved to Lewistown, Illinois, where he attended high school and had his first publication in the Chicago Daily News. The culture around Lewistown, in addition to the town’s cemetery at Oak Hill, and the nearby Spoon River were the inspirations for many of his works, most notably Spoon River Anthology, his most famous and acclaimed work. He attended Knox Academy in 1889–90, a now defunct preparatory program run by Knox College, but was forced to leave due to his family’s inability to finance his education. After working in his father’s law office, he was admitted to the Illinois bar and moved to Chicago, where he established a law partnership in 1893 with the law firm of Kickham Scanlan. He married twice. In 1898 he married Helen M. Jenkins, the daughter of Robert Edwin Jenkins, a lawyer in Chicago, and had three children. During his law partnership with Clarence Darrow from 1903 to 1908, Masters defended the poor. In 1911 he started his own law firm, despite three years of unrest (1908–11) caused by extramarital affairs and an argument with Darrow. Two of his children followed him with literary careers. His daughter Marcia pursued poetry, while his son Hilary Masters became a novelist. Hilary and his half-brother Hardin wrote a memoir of their father. Masters died at a nursing home on March 5, 1950, in Melrose Park, Pennsylvania, age 81. He is buried in Oakland cemetery in Petersburg, Illinois. His epitaph includes his poem, “To-morrow is My Birthday” from Toward the Gulf (1918): Good friends, let’s to the fields…After a little walk and by your pardon, I think I’ll sleep, there is no sweeter thing.Nor fate more blessed than to sleep. I am a dream out of a blessed sleep-Let’s walk, and hear the lark. Family history Edgar’s father was Hardin Wallace Masters, whose father was Squire Davis Masters, whose father was Thomas Masters, whose father was Hillery Masters, the son of Robert Masters (born c. 1715, Prince George’s County, Maryland, the son of William W. Masters and wife Mary Veatch Masters). Edgar Lee Masters wrote in his autobiography, Across Spoon River (1936), that his ancestor Hillery Masters was the son of “Knotteley” Masters, but family genealogies show that Hillery and Notley Masters were, in fact, brothers. Poetry Masters first published his early poems and essays under the pseudonym Dexter Wallace (after his mother’s maiden name and his father’s middle name) until the year 1903, when he joined the law firm of Clarence Darrow. Masters began developing as a notable American poet in 1914, when he began a series of poems (this time under the pseudonym Webster Ford) about his childhood experiences in Western Illinois, which appeared in Reedy’s Mirror, a St. Louis publication. In 1915 the series was bound into a volume and re-titled Spoon River Anthology. Years later, he wrote a memorable and invaluable account of the book’s background and genesis, his working methods and influences, as well as its reception by the critics, favorable and hostile, in an autobiographical article notable for its human warmth and general interest. Although he never matched the success of his Spoon River Anthology, he did publish several other volumes of poems including Book of Verses in 1898, Songs and Sonnets in 1910, The Great Valley in 1916, Song and Satires in 1916, The Open Sea in 1921, The New Spoon River in 1924, Lee in 1926, Jack Kelso in 1928, Lichee Nuts in 1930, Gettysburg, Manila, Acoma in 1930, Godbey, sequel to Jack Kelso in 1931, The Serpent in the Wilderness in 1933, Richmond in 1934, Invisible Landscapes in 1935, The Golden Fleece of California in 1936, Poems of People in 1936, The New World in 1937, More People in 1939, Illinois Poems in 1941, and Along the Illinois in 1942. Lincoln: the Man In 1931 Masters published the biography Lincoln: the Man, which demythologizes Abraham Lincoln, portraying him as a tool of bankers wanting a new Bank of the United States, “that political system which doles favors to the strong in order to win and keep their adherence to the government”, and advocates “a people taxed to make profits for enterprises that cannot stand alone”. He claimed the Whig Party led by Lincoln’s mentor Henry Clay “had no platform to announce because its principles were plunder and nothing else.” Quotations from the book: “The political history of America has been written for the most part by those who were unfriendly to the theory of a confederated republic, or who did not understand it. It has been written by devotees of the protective principle [tariff], by centralists, and to a large degree by New England.” “For in six weeks he was to inaugurate a war without the American people having anything to say about it. He was to call for and send troops into the South, and thus stir that psychology of hate and fear from which a people cannot extricate themselves, though knowing and saying that the war was started by usurpation. Did he mean that he would bow to the American people when the law was laid down by their courts, through which alone the law be interpreted as the Constitutional voice of the people? No, he did not mean that; because when Taney decided that Lincoln had no power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, Lincoln flouted and trampled the decision of the court.” “The War between the States demonstrated that salvation is not of the Jews, but of the Greeks. The World War added to this proof; for Wilson did many things that Lincoln did, and with Lincoln as authority for doing them. Perhaps it will happen again that a few men, deciding what is a cause of war, and what is necessary to its successful prosecution, may, as Lincoln and Wilson did, seal the lips of discussion and shackle the press; but no less the ideal of a just state, which has founded itself in reason and in free speech, will remain.” Notable works Poetry * A Book of Verses (1898) * Songs and Sonnets (1910) * Spoon River Anthology (1915) * Songs and Satires (1916) * Fiddler Jones (1916) * The Great Valley (New York: Macmillan Co., 1916) * Toward the Gulf (New York: Macmillan Co., 1918) * Starved Rock (New York: Macmillan Co., 1919) * Jack Kelso: A Dramatic Poem (1920) * Domesday Book (New York: Macmillan Co., 1920) * The Open Sea (New York: Macmillan Co., 1921) * The New Spoon River (New York: Macmillan Co., 1924) * Selected Poems (1925) * Lichee-Nut Poems (American Mercury, Jan. 1925) * Lee: A Dramatic Poem (1926) * Godbey: A Dramatic Poem (1931), sequel to Jack Kelso (1920) * The Serpent in the Wilderness (1933) * Richmond: A Dramatic Poem (1934) * Invisible Landscapes (1935) * Poems of People (1936) * The Golden Fleece of California (1936) (poetic narrative) * The New World (1937) * More People (1939) * Illinois Poems (1941) * Along the Illinois (1942) * Silence (1946) * George Gray * Many Soldiers * The Unknown Biographies * Children of the Market Place: A Fictitious Autobiography (New York: Macmillan Co., 1922). Life of Stephen Douglas. * Levy Mayer and the New Industrial Era (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927). Chicago attorney Levy Mayer (1858-1922). * Lincoln: The Man (1931) * Vachel Lindsay: A Poet in America (1935) * Across Spoon River: An Autobiography (memoir) (1936) * Whitman (1937) * Mark Twain: A Portrait (1938) Books * The New Star Chamber and Other Essays (1904) * The Blood of the Prophets (1905) (play) * Althea (1907) (play) * The Trifler (1908) (play) * Mitch Miller (novel) (1920) * Skeeters Kirby (novel) (1923) * The Nuptial Flight (novel) (1923) * Kit O’Brien (novel) (1927) * The Fate of the Jury: An Epilogue to Domesday Book (1929) * Gettysburg, Manila, Acoma: Three Plays (1930) * The Tale of Chicago (1933) * The Tide of Time (novel) (1937) * The Sangamon (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1942, 1988) Awards & honors Masters was awarded the Mark Twain Silver Medal in 1936, the Poetry Society of America medal in 1941, the Academy of American Poets Fellowship in 1942, and the Shelly Memorial Award in 1944. In 2014, he was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Lee_Masters

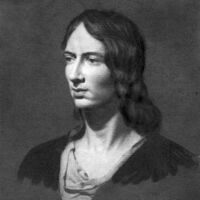

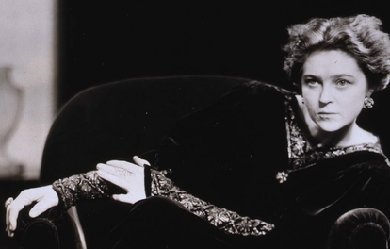

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death. Barrett Browning opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of slavers and her support for the abolitionist cause. The poems opposing slavery include "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation"; in the first she describes the experience of a slave woman who is whipped, raped, and made pregnant as she curses the slavers. She declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Emancipation Act abolishing slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833, despite the fact that her father believed that Abolitionism would ruin his business.

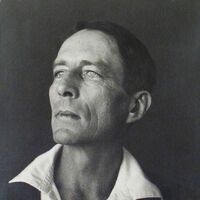

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and epic form, but he is also known for his shorter verse and is considered an icon of the environmental movement. Influential and highly regarded in some circles, despite or because of his philosophy of "inhumanism," Jeffers believed that transcending conflict required human concerns to be de-emphasized in favor of the boundless whole. This led him to oppose U.S. participation in World War II, a stand that was controversial at the time. Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), the son of a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, Reverend Dr. William Hamilton Jeffers, and Annie Robinson Tuttle. His brother was Hamilton Jeffers, who became a well-known astronomer, working at Lick Observatory. His family was supportive of his interest in poetry. He traveled through Europe during his youth and attended school in Switzerland. He was a child prodigy, interested in classics and Greek and Latin language and literature. At sixteen he entered Occidental College. At school, he was an avid outdoorsman, and active in the school's literary societies. After he graduated from Occidental, Jeffers went to the University of Southern California to study at first literature, and then medicine. He met Una Call Kuster in 1906; she was three years older than he was, a graduate student, and the wife of a Los Angeles attorney. In 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he abandoned after less than one year, at which time he returned to Los Angeles. Sometime before this, he and Una had begun an affair that became a scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times in 1912. After Una spent some time in Europe to quiet things down, the two were married in 1913, and moved to Carmel, California, where Jeffers constructed Tor House and Hawk Tower. The couple had a daughter who died a day after birth in 1914, and then twin sons (Donnan and Garth) in 1916. Una died of cancer in 1950. Jeffers died in 1962; an obituary can be found in the New York Times, January 22, 1962. Poetic career In the 1920s and 1930s, at the height of his popularity, Jeffers was famous for being a tough outdoorsman, living in relative solitude and writing of the difficulty and beauty of the wild. He spent most of his life in Carmel, California, in a granite house that he had built himself called "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Tor is a term for a craggy outcrop or lookout. Before Jeffers and Una purchased the land where Tor House would be built, they rented two cottages in Carmel, and enjoyed many afternoon walks and picnics at the "tors" near the site that would become Tor House. To build the first part of Tor House, a small, two story cottage, Jeffers hired a local builder, Michael Murphy. He worked with Murphy, and in this short, informal apprenticeship, he learned the art of stonemasonry. He continued adding on to Tor House throughout his life, writing in the mornings and working on the house in the afternoon. Many of his poems reflect the influence of stone and building on his life. He later built a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. While he had not visited Ireland at this point in his life, it is possible that Hawk Tower is based on Francis Joseph Bigger's 'Castle Séan' at Ardglass, County Down, which had also in turn influenced Yeats' poets tower, Thoor Ballylee. Construction on Tor House continued into the late 1950s and early 1960s, and was completed by his eldest son. The completed residence was used as a family home until his descendants decided to turn it over to the Tor House Foundation, formed by Ansel Adams, for historic preservation. The romantic Gothic tower was named after a hawk that appeared while Jeffers was working on the structure, and which disappeared the day it was completed. The tower was a gift for his wife Una, who had a fascination for Irish literature and stone towers. In Una's special room on the second floor were kept many of her favorite items, photographs of Jeffers taken by the artist Weston, plants and dried flowers from Shelley's grave, and a rosewood melodeon which she loved to play. The tower also included a secret interior staircase – a source of great fun for his young sons. During this time, Jeffers published volumes of long narrative blank verse that shook up the national literary scene. These poems, including Tamar and Roan Stallion, introduced Jeffers as a master of the epic form, reminiscent of ancient Greek poets. These poems were full of controversial subject matter such as incest, murder and parricide. Jeffers' short verse includes "Hurt Hawks," "The Purse-Seine" and "Shine, Perishing Republic." His intense relationship with the physical world is described in often brutal and apocalyptic verse, and demonstrates a preference for the natural world over what he sees as the negative influence of civilization. Jeffers did not accept the idea that meter is a fundamental part of poetry, and, like Marianne Moore, claimed his verse was not composed in meter, but "rolling stresses." He believed meter was imposed on poetry by man and not a fundamental part of its nature. nitially, Tamar and Other Poems received no acclaim, but when East Coast reviewers discovered the work and began to compare Jeffers to Greek tragedians, Boni & Liveright reissued an expanded edition as Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925). In these works, Jeffers began to articulate themes that contributed to what he later identified as Inhumanism. Mankind was too self-centered, he complained, and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." Jeffers's longest and most ambitious narrative, The Women at Point Sur (1927), startled many of his readers, heavily loaded as it was with Nietzschean philosophy. The balance of the 1920s and the early 1930s were especially productive for Jeffers, and his reputation was secure. In 1934, he made the acquaintance of the philosopher J Krishnamurti and was struck by the force of Krishnamurti's person. He wrote a poem entitled "Credo" which many feel refers to Krishnamurti. In Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Dear Judas and Other Poems (1929), Descent to the Dead, Poems Written in Ireland and Great Britain (1931), Thurso's Landing (1932), and Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Jeffers continued to explore the questions of how human beings could find their proper relationship (free of human egocentrism) with the divinity of the beauty of things. These poems, set in the Big Sur region (except Dear Judas and Descent to the Dead), enabled Jeffers to pursue his belief that the natural splendor of the area demanded tragedy: the greater the beauty, the greater the demand. As Euripides had, Jeffers began to focus more on his own characters' psychologies and on social realities than on the mythic. The human dilemmas of Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Medea fascinated him. Many books followed Jeffers' initial success with the epic form, including an adaptation of Euripides' Medea, which became a hit Broadway play starring Dame Judith Anderson. D. H. Lawrence, Edgar Lee Masters, Benjamin De Casseres, and George Sterling were close friends of Jeffers, Sterling having the longest and most intimate relationship with him. While living in Carmel, Jeffers became the focal point for a small but devoted group of admirers. At the peak of his fame, he was one of the few poets to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. He was also asked to read at the Library of Congress, and was posthumously put on a U.S. postage stamp. Part of the decline of Jeffers' popularity was due to his staunch opposition to the United States' entering World War II. In fact, his book The Double Axe and Other Poems (1948), a volume of poems that was largely critical of U.S. policy, came with an extremely unconventional note from Random House that the views expressed by Jeffers were not those of the publishing company. Soon after, his work was received negatively by several influential literary critics. Several particularly scathing pieces were penned by Yvor Winters, as well as by Kenneth Rexroth, who had been very positive in his earlier commentary on Jeffers' work. Jeffers would publish poetry intermittently during the 1950s but his poetry never again attained the same degree of popularity that it had in the 1920s and the 1930s. Inhumanism Jeffers coined the word inhumanism, the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." In the famous poem "Carmel Point," Jeffers called on humans to "uncenter" themselves. In "The Double Axe," Jeffers explicitly described inhumanism as "a shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence. ... This manner of thought and feeling is neither misanthropic nor pessimist. ... It offers a reasonable detachment as rule of conduct, instead of love, hate and envy ... it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty." In The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers,the first in-depth study of Jeffers not written by one of his circle, poet and critic J. Radcliffe Squires addresses the question of a reconciliation of the beauty of the world and potential beauty in mankind: “Jeffers has asked us to look squarely at the universe. He has told us that materialism has its message, its relevance, and its solace. These are different from the message, relevance, and solace of humanism. Humanism teaches us best why we suffer, but materialism teaches us how to suffer.” Influence His poems have been translated into many languages and published all over the world. Outside of the United States he is most popular in Japan and the Czech Republic. William Everson, Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, and Mark Jarman are just a few recent authors who have been influenced by Jeffers. Charles Bukowski remarked that Jeffers was his favorite poet. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz also took an interest in Jeffers' poetry and worked as a translator for several volumes of his poems. Jeffers also exchanged some letters with his Czech translator and popularizer, the poet Kamil Bednář. Writer Paul Mooney (1904–1939), son of American Indian authority James Mooney (1861–1921) and collaborator of travel writer Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), "was known always to carry with him (a volume of Jeffers) as a chewer might carry a pouch of tobacco ... and, like Jeffers," writes Gerry Max in Horizon Chasers, "worshipped nature ... (taking) refuge (from the encroachments of civilization) in a sort of chthonian mysticism rife with Greek dramatic elements ..." Jeffers was an inspiration and friend to western U.S. photographers of the early twentieth century, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Morley Baer. In fact, the elegant book of Baer's photographs juxtaposed with Jeffers' poetry, combines the creative talents of those two residents of the Big Sur coast. Although Jeffers has largely been marginalized in the mainstream academic community over the last thirty years, several important contemporary literary critics, including Albert Gelpi of Stanford University, and poet, critic and NEA chairman Dana Gioia, have consistently cited Jeffers as a formidable presence in modern literature. His poem "The Beaks of Eagles" was made into a song by The Beach Boys on their album Holland (1973). Two lines from Jeffers' poem "We Are Those People" are quoted toward the end of the 2008 film Visioneers. Several lines from Jeffers' poem "Wise Men in Their Bad Hours" ("Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made / Something more equal to the centuries / Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.") appear in Christopher McCandless' diary. Robinson Jeffers is mentioned in the 2004 film I Heart Huckabees by the character Albert Markovski played by Jason Schwartzman, when defending Jeffers as a nature writer against another character's claim that environmentalism is socialism. Markovski says, "Henry David Thoreau, Robinson Jeffers, the National Geographic Society...all socialists?" Further reading and research The largest collections of Jeffers' manuscripts and materials are in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and in the libraries at Occidental College, the University of California, and Yale University. A collection of his letters has been published as The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1887–1962 (1968). Other books of criticism and poetry by Jeffers are: Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years (1949), Themes in My Poems (1956), Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems (1965), The Alpine Christ and Other Poems (1974), What Odd Expedients" and Other Poems (1981), and Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers (1987). Stanford University Press recently released a five-volume collection of the complete works of Robinson Jeffers. In an article titled, "A Black Sheep Joins the Fold", written upon the release of the collection in 2001, Stanford Magazine commented that it was remarkable that, due to a number of circumstances, "there was never an authoritative, scholarly edition of California’s premier bard" until the complete works published by Stanford. Biographical studies include George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (1926); Louis Adamic, Robinson Jeffers (1929); Melba Bennett, Robinson Jeffers and the Sea (1936) and The Stone Mason of Tor House (1966); Radcliffe Squires, The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers (1956); Edith Greenan, Of Una Jeffers (1939); Mabel Dodge Luhan, Una and Robin (1976; written in 1933); Ward Ritchie, Jeffers: Some Recollections of Robinson Jeffers (1977); and James Karman, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of California (1987). Books about Jeffers's career include L. C. Powell, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and His Work (1940; repr. 1973); William Everson, Robinson Jeffers: Fragments of an Older Fury (1968); Arthur B. Coffin, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of Inhumanism (1971); Bill Hotchkiss, Jeffers: The Sivaistic Vision (1975); James Karman, ed., Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers (1990); Alex Vardamis The Critical Reputation of Robinson Jeffers (1972); and Robert Zaller, ed., Centennial Essays for Robinson Jeffers (1991). The Robinson Jeffers Newsletter, ed. Robert Brophy, is a valuable scholarly resource. In a rare recording, Jeffers can be heard reading his "The Day Is A Poem" (September 19, 1939) on Poetry Speaks – Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Narrated by Charles Osgood (Sourcebooks, Inc., c2001), Disc 1, #41; including text, with Robert Hass on Robinson Jeffers, pp. 88–95. Jeffers was also on the cover of Time – The Weekly Magazine, April 4, 1932 (pictured on p. 90. Poetry Speaks). Jeffers Studies, a journal of research on the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and related topics, is published semi-annually by the Robinson Jeffers Association. Bibliography * Flagons and Apples. Los Angeles: Grafton, 1912. * Californians. New York: Macmillan, 1916. * Tamar and Other Poems. New York: Peter G. Boyle, 1924. * Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925. * The Women at Point Sur. New York: Liveright, 1927. * Cawdor and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1928. * Dear Judas and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1929. * Thurso's Landing and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1932. * Give Your Heart to the Hawks and other Poems. New York: Random House, 1933. * Solstice and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1935. * Such Counsels You Gave To Me and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1937. * The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. New York: Random House, 1938. * Be Angry at the Sun. New York: Random House, 1941. * Medea. New York: Random House, 1946. * The Double Axe and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1948. * Hungerfield and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1954. * The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1963. * Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1965. * Stones of the Sur. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robinson_Jeffers

Alexis karpouzos was born in Athens on April 9, 1967, after attending philosophy and social studies courses at the Athens School of Philosophy and political science courses at the Athens Law School, he continued his studies in psychoanalysis and the psychology of learning. In 1998 founded the international center of learning, research and culture, a wisdom forum for studying issues of science and society in an integral way. He has been a visioner in the development of post-history sense of cosmic unity and the integral consciousness. The poetic thought of Alexis karpouzos is a expressions of soul's inner experiences, expression of universality. The inspiring visual images and the symbolic use of language offer a description of elevating experiences of consciousness, a glimpse of higher worlds. His philosophy speak to the human experience from a universal perspective, transcending all religions, cultural and national boundaries. Using vivid images and a direct language that speaks to the heart, his philosophy evokes a sense of deep communication with the collective unconscious, a sense of connection to all the creatures of the world, compassion for others, admiration for the beauty of nature, reverence for all life, and an abiding faith in the invisible touch of world. Alexis karpouzos thoughts are often terse and paradoxical, challenging us to to break out of the box of limiting beliefs and see things from a new perspective. Above all, Alexis karpouzos continually calls to us to wake up and explore the mysteries within our own selves, i.e. the mysteries of universe.

Emily Jane Brontë (30 July 1818 – 19 December 1848) was an English novelist and poet, best remembered for her solitary novel, Wuthering Heights, now considered a classic of English literature. Emily was the third eldest of the four surviving Brontë siblings, between the youngest Anne and her brother Branwell. She published under the pen name Ellis Bell. She was born in Thornton, near Bradford in Yorkshire, to Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë. She was the younger sister of Charlotte Brontë and the fifth of six children. In 1824, the family moved to Haworth, where Emily's father was perpetual curate, and it was in these surroundings that their literary gifts flourished.

Eugene Field, Sr. (September 2, 1850 – November 4, 1895) was an American writer, best known for his children's poetry and humorous essays. Field was born in St. Louis, Missouri where today his boyhood home is open to the public as The Eugene Field House and St. Louis Toy Museum. After the death of his mother in 1856, he was raised by a cousin, Mary Field French, in Amherst, Massachusetts.

.jpeg)

Thomas Moore (28 May 1779 – 25 February 1852), also known as Tom Moore, was an Irish writer, poet, and lyricist celebrated for his Irish Melodies. His setting of English-language verse to old Irish tunes marked the transition in popular Irish culture from Irish to English. Politically, Moore was recognised in England as a press, or "squib", writer for the aristocratic Whigs; in Ireland he was accounted a Catholic patriot.

George Henry Boker (October 6, 1823 – January 2, 1890) was an American poet, playwright, and diplomat. Boker was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His father was Charles S. Boker, a wealthy banker, whose financial expertness weathered the Girard National Bank through the panic years of 1838-40, and whose honour, impugned after his 1857 death, was defended many years later by his son in “The Book of the Dead.” Charles Boker was also a director of the Mechanics National Bank.

I have been a hopeless romantic since I was a young boy. I have always been drawn to relationships and the experience of love. The exhilaration and emotions that flood into and coarse through those that are in love is the most intoxicating feeling possible, at least in my opinion. As you read these poems, you are reading my story. I write about my thoughts, my feelings, and my experiences. Forgive me if my writings are not of your flavor as I never did read much poetry from others.

George Meredith, OM (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and poet of the Victorian era. Meredith was born in Portsmouth, England, a son and grandson of naval outfitters. His mother died when he was five. At the age of 14 he was sent to a Moravian School in Neuwied, Germany, where he remained for two years. He read law and was articled as a solicitor, but abandoned that profession for journalism and poetry. He collaborated with Edward Gryffydh Peacock, son of Thomas Love Peacock in publishing a privately circulated literary magazine, the Monthly Observer. He married Edward Peacock's widowed sister Mary Ellen Nicolls in 1849 when he was twenty-one years old and she was twenty-eight. He collected his early writings, first published in periodicals, into Poems, published to some acclaim in 1851. His wife ran off with the English Pre-Raphaelite painter Henry Wallis [1830–1916] in 1858; she died three years later. The collection of "sonnets" entitled Modern Love (1862) came of this experience as did The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, his first "major novel". He married Marie Vulliamy in 1864 and settled in Surrey. He continued writing novels and poetry, often inspired by nature. His writing was characterised by a fascination with imagery and indirect references. He had a keen understanding of comedy and his Essay on Comedy (1877) is still quoted in most discussions of the history of comic theory. In The Egoist, published in 1879, he applies some of his theories of comedy in one of his most enduring novels. Some of his writings, including The Egoist, also highlight the subjugation of women during the Victorian period. During most of his career, he had difficulty achieving popular success. His first truly successful novel was Diana of the Crossways published in 1885. Meredith supplemented his often uncertain writer's income with a job as a publisher's reader. His advice to Chapman and Hall made him influential in the world of letters. His friends in the literary world included, at different times, William and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Leslie Stephen, Robert Louis Stevenson, George Gissing and J. M. Barrie. His contemporary Sir Arthur Conan Doyle paid him homage in the short-story The Boscombe Valley Mystery, when Sherlock Holmes says to Dr. Watson during the discussion of the case, "And now let us talk about George Meredith, if you please, and we shall leave all minor matters until to-morrow." Oscar Wilde, in his dialogue The Decay of Lying, implies that Meredith, along with Balzac, is his favourite novelist, saying "Ah, Meredith! Who can define him? His style is chaos illumined by flashes of lightning". In 1868 he was introduced to Thomas Hardy by Frederick Chapman of Chapman & Hall the publishers. Hardy had submitted his first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady. Meredith advised Hardy not to publish his book as it would be attacked by reviewers and destroy his hopes of becoming a novelist. Meredith felt the book was too bitter a satire on the rich and counselled Hardy to put it aside and write another 'with a purely artistic purpose' and more of a plot. Meredith spoke from experience; his first big novel, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, was judged so shocking that Mudie's circulating library had cancelled an order of 300 copies. Hardy continued to try and publish the novel: however it remained unpublished, though he clearly took Meredith's advice seriously. Before his death, Meredith was honoured from many quarters: he succeeded Lord Tennyson as president of the Society of Authors; in 1905 he was appointed to the Order of Merit by King Edward VII. In 1909, he died at his home in Box Hill, Surrey. Works Essays * Essay on Comedy (1877) Novels * The Shaving of Shagpat (1856) * Farina (1857) * The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1859) * Evan Harrington (1861) * Emilia in England (1864), republished as Sandra Belloni in 1887 * Rhoda Fleming (1865) * Vittoria (1867) * The Adventures of Harry Richmond (1871) * Beauchamp's Career (1875) * The House on the Beach (1877) * The Case of General Ople and Lady Camper (1877) * The Tale of Chloe (1879) * The Egoist (1879) * The Tragic Comedians (1880) * Diana of the Crossways (1885) * One of our Conquerors (1891) * Lord Ormont and his Aminta (1894) * The Amazing Marriage (1895) * Celt and Saxon (1910) Poetry * Poems (1851) * Modern Love (1862) * Poems and Lyrics of the Joy of Earth (1883) * The Woods of Westermain (1883) * A Faith on Trial (1885) * Ballads and Poems of Tragic Life (1887) * A Reading of Earth (1888) * The Empty Purse (1892) * Odes in Contribution to the Song of French History(1898) * A Reading of Life (1901) * Last Poems (1909) * Lucifer in Starlight * The Lark Ascending (the inspiration for Vaughan Williams' instrumental work The Lark Ascending). References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Meredith

“L'amour n'est pas un feu qu'on renferme dans une âme : Tout nous trahit, la voix, le silence, les yeux; Et les feux mal couverts n'en éclatent que mieux.”Racine Love is not a fire that one encloses in a soul: Everything betrays us, the voice, the silence, the eyes; And poorly covered fires only break out better. ” Racine

Wallace Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, on October 2, 1879. He attended Harvard University as an undergraduate from 1897 to 1900. He planned to travel to Paris as a writer, but after a working briefly as a reporter for the New York Herald Times, he decided to study law. He graduated with a degree from New York Law School in 1903 and was admitted to the U.S. Bar in 1904. He practised law in New York City until 1916. Though he had serious determination to become a successful lawyer, Stevens had several friends among the New York writers and painters in Greenwich Village, including the poets William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and E. E. Cummings. In 1914, under the pseudonym "Peter Parasol," he sent a group of poems under the title "Phases" to Harriet Monroe for a war poem competition for Poetry magazine. Stevens did not win the prize, but was published by Monroe in November of that year. Stevens moved to Connecticut in 1916, having found employment at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Co., of which he became vice president in 1934. He had began to establish an identity for himself outside the world of law and business, however, and his first book of poems, Harmonium, published in 1923, exhibited the influence of both the English Romantics and the French symbolists, an inclination to aesthetic philosophy, and a wholly original style and sensibility: exotic, whimsical, infused with the light and color of an Impressionist painting. For the next several years, Stevens focused on his business life. He began to publish new poems in 1930, however, and in the following year, Knopf published an second edition of Harmonium, which included fourteen new poems and left out three of the decidedly weaker ones. More than any other modern poet, Stevens was concerned with the transformative power of the imagination. Composing poems on his way to and from the office and in the evenings, Stevens continued to spend his days behind a desk at the office, and led a quiet, uneventful life. Though now considered one of the major American poets of the century, he did not receive widespread recognition until the publication of his Collected Poems, just a year before his death. His major works include Ideas of Order (1935), The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937), Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942), and a collection of essays on poetry, The Necessary Angel (1951). Stevens died in Hartford in 1955. Poetry Harmonium (1923) Ideas of Order (1935) Owl's Clover (1936) The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937) Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942) Parts of a World (1942) Esthétique du Mal (1945) Three Academic Pieces (1947) Transport to Summer (1947) Primitive Like an Orb (1948) Auroras of Autumn (1950) Collected Poems (1954) Opus Posthumous (1957) The Palm at the End of the Mind (1967) Prose The Necessary Angel (1951) Plays Three Travellers Watch the Sunrise (1916) Carlos Among the Candles (1917) References Poets.org — http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/124

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist and journalist. His work is marked by clarity, intelligence and wit, awareness of social injustice, opposition to totalitarianism, and belief in democratic socialism. Considered perhaps the 20th century's best chronicler of English culture, Orwell wrote literary criticism, poetry, fiction and polemical journalism. He is best known for the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and the allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945), which together have sold more copies than any two books by any other 20th-century author. His book Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, is widely acclaimed, as are his numerous essays on politics, literature, language and culture. In 2008, The Times ranked him second on a list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”.

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the circumstances of his imprisonment, followed by his early death. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome (1891) in French in Paris but it was refused a licence. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London.

I've been in a serious relationship for 11yrs now, with my Sweetie-pie. We met @ a club in Lafayette, LA, called Jules. A local gay bar, that was in the heart of downtown, but alas it shut down shortly after we met. I always think of Fate having a hand in our meeting, because I had sent my longing for a love to love into the universe & wasn't looking to fall in love when we met. Also I had just driven 8+ hrs from West Texas after visiting relatives & didn't plan on going out. But for some reason I felt the urge to get my dance on & wallah! The rest is history. I get asked quite often about my nationality, but it comes out wrong like ppl asking "what are you" for which I reply "human & you?" So for those of you curious of my nationality/ethnicity I'm Panamanian, Mexican, African-American & Blackfoot Native American. My mom claims she's got Apache blood as well, but it's just her belief (yet to be confirmed). My grandparents on my mom's side are Swedish & Norwegian, so yeah, my family looks like the League of Nations if you were to see us all gathered at a family reunion. A fitting rainbow of nationalities. UPDATE! It's been years since I've updated my profile. fast forward 7yrs later and I currently am selling crystals on Etsy @skyygems. Im now living in Houston, TX, still with my love whom I met at that club all those yrs ago. We have a miniature poodle named Ford (my sweetie's doing, I wasn't feeling that name) and we are now enjoying downtown living.

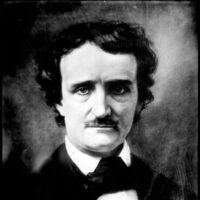

Edgar Allan Poe (born Edgar Poe, January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre. He is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career. He was born as Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts; he was orphaned young when his mother died shortly after his father abandoned the family. Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan, of Richmond, Virginia, but they never formally adopted him. He attended the University of Virginia for one semester but left due to lack of money. After enlisting in the Army and later failing as an officer's cadet at West Point, Poe parted ways with the Allans. His publishing career began humbly, with an anonymous collection of poems, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), credited only to “a Bostonian”.

Edmund Spenser (c. 1552 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and is considered one of the greatest poets in the English language. Edmund Spenser was born in East Smithfield, London, around the year 1552, though there is some ambiguity as to the exact date of his birth. As a young boy, he was educated in London at the Merchant Taylors' School and matriculated as a sizar at Pembroke College, Cambridge. While at Cambridge he became a friend of Gabriel Harvey and later consulted him, despite their differing views on poetry. In 1578 he became for a short time secretary to John Young, Bishop of Rochester. In 1579 he published The Shepheardes Calender and around the same time married his first wife, Machabyas Childe. In July 1580 Spenser went to Ireland in service of the newly appointed Lord Deputy, Arthur Grey, 14th Baron Grey de Wilton. When Grey was recalled to England, he stayed on in Ireland, having acquired other official posts and lands in the Munster Plantation. At some time between 1587 and 1589 he acquired his main estate at Kilcolman, near Doneraile in North Cork. Among his acquaintances in the area was Walter Raleigh, a fellow colonist. He later bought a second holding to the south, at Rennie, on a rock overlooking the river Blackwater in North Cork. Its ruins are still visible today. A short distance away grew a tree, locally known as "Spenser's Oak" until it was destroyed in a lightning strike in the 1960s. Local legend has it that he penned some of The Faerie Queene under this tree. In 1590 Spenser brought out the first three books of his most famous work, The Faerie Queene, having travelled to London to publish and promote the work, with the likely assistance of Raleigh. He was successful enough to obtain a life pension of £50 a year from the Queen. He probably hoped to secure a place at court through his poetry, but his next significant publication boldly antagonised the queen's principal secretary, Lord Burghley, through its inclusion of the satirical Mother Hubberd's Tale. He returned to Ireland. By 1594 Spenser's first wife had died, and in that year he married Elizabeth Boyle, to whom he addressed the sonnet sequence Amoretti. The marriage itself was celebrated in Epithalamion. In 1596 Spenser wrote a prose pamphlet titled, A View of the Present State of Ireland. This piece, in the form of a dialogue, circulated in manuscript, remaining unpublished until the mid-seventeenth century. It is probable that it was kept out of print during the author's lifetime because of its inflammatory content. The pamphlet argued that Ireland would never be totally 'pacified' by the English until its indigenous language and customs had been destroyed, if necessary by violence. Later on, during the Nine Years War in 1598, Spenser was driven from his home by the native Irish forces of Aodh Ó Néill. His castle at Kilcolman was burned, and Ben Jonson (who may have had private information) asserted that one of his infant children died in the blaze. In the year after being driven from his home, Spenser travelled to London, where he died aged forty-six. His coffin was carried to his grave in Westminster Abbey by other poets, who threw many pens and pieces of poetry into his grave with many tears. His second wife survived him and remarried twice. Rhyme and reason Thomas Fuller included in his Worthies of England a story that The Queen told her treasurer, William Cecil, to pay Spenser one hundred pounds for his poetry. The treasurer, however, objected that the sum was too much. She said, "Then give him what is reason". After a long while without receiving his payment, Spenser gave the Queen this quatrain on one of her progresses: I was promis'd on a time, To have a reason for my rhyme: From that time unto this season, I receiv'd nor rhyme nor reason. She immediately ordered the treasurer pay Spenser the original £100. This story seems to have attached itself to Spenser from Thomas Churchyard, who apparently had difficulty in getting payment of his pension (the only other one Elizabeth awarded to a poet). Spenser seems to have had no difficulty in receiving payment when it was due, the pension being collected for him by his publisher, Ponsonby. The Faerie Queene Spenser's masterpiece is the epic poem The Faerie Queene. The first three books of The Faerie Queene were published in 1590, and a second set of three books were published in 1596. Spenser originally indicated that he intended the poem to consist of twelve books, so the version of the poem we have today is incomplete. Despite this, it remains one of the longest poems in the English language. It is an allegorical work, and can be read (as Spenser presumably intended) on several levels of allegory, including as praise of Queen Elizabeth I. In a completely allegorical context, the poem follows several knights in an examination of several virtues. In Spenser's "A Letter of the Authors," he states that the entire epic poem is "cloudily enwrapped in allegorical devises," and that the aim behind The Faerie Queene was to “fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline.” Shorter poems Spenser published numerous relatively short poems in the last decade of the sixteenth century, almost all of which consider love or sorrow. In 1591 he published Complaints, a collection of poems that express complaints in mournful or mocking tones. Four years later, in 1595, Spenser published Amoretti and Epithalamion. This volume contains eighty-nine sonnets commemorating his courtship of Elizabeth Boyle. In “Amoretti,” Spenser uses subtle humour and parody while praising his beloved, reworking Petrarchism in his treatment of longing for a woman. “Epithalamion,” similar to “Amoretti,” deals in part with the unease in the development of a romantic and sexual relationship. It was written for his wedding to his young bride, Elizabeth Boyle. The poem consists of 365 long lines, corresponding to the days of the year; 68 short lines, claimed to represent the sum of the 52 weeks, 12 months, and 4 seasons of the annual cycle; and 24 stanzas, corresponding to the diurnal and sidereal hours.[citation needed] Some have speculated that the attention to disquiet in general reflects Spenser’s personal anxieties at the time, as he was unable to complete his most significant work, The Faerie Queene. In the following year Spenser released "Prothalamion," a wedding song written for the daughters of a duke, allegedly in hopes to gain favor in the court. The Spenserian stanza and sonnet Spenser used a distinctive verse form, called the Spenserian stanza, in several works, including The Faerie Queene. The stanza's main meter is iambic pentameter with a final line in iambic hexameter (having six feet or stresses, known as an Alexandrine), and the rhyme scheme is ababbcbcc. He also used his own rhyme scheme for the sonnet. Influences and influenced Though Spenser was well read in classical literature, scholars have noted that his poetry does not rehash tradition, but rather is distinctly his. This individuality may have resulted, to some extent, from a lack of comprehension of the classics. Spenser strove to emulate such ancient Roman poets as Virgil and Ovid, whom he studied during his schooling, but many of his best-known works are notably divergent from those of his predecessors.[15] The language of his poetry is purposely archaic, reminiscent of earlier works such as The Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer and Il Canzoniere of Francesco Petrarca, whom Spenser greatly admired. Spenser was called a Poets' Poet and was admired by William Wordsworth, John Keats, Lord Byron, and Alfred Lord Tennyson, among others. Walter Raleigh wrote a dedicatory sonnet to The Faerie Queene in 1590, in which he claims to admire and value Spenser’s work more so than any other in the English language. In the eighteenth century, Alexander Pope compared Spenser to “a mistress, whose faults we see, but love her with them all." A View of the Present State of Ireland n his work A View of the present State of Ireland, Spenser devises his ideas to the issues of the nation of Ireland. These views are suspected to not be his own but based on the work of his predecessor, Lord Arthur Grey de Wilton who was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1580 (Henley 19, 168-69). Lord Grey was a major figure in Ireland at the time and Spenser was influenced greatly by his ideals and his work in the country, as well as that of his fellow countrymen also living in Ireland at the time (Henley 169). The goal of this piece was to show that Ireland was in great need of reform. Spenser believed that “Ireland is a diseased portion of the State, it must first be cured and reformed, before it could be in a position to appreciate the good sound laws and blessings of the nation” (Henley 178). In A View of the present State of Ireland, Spenser categorizes the “evils” of the Irish people into three prominent categories: laws, customs, and religion (Spenser). These three elements work together in creating the disruptive and degraded people. One example given in the work is the native law system called “Brehon Law” which trumps the established law given by the English monarchy (Spenser). This system has its own court and way of dealing with infractions. It has been passed down through the generations and Spenser views this system as a native backward custom which must be destroyed. Spenser also recommended scorched earth tactics, such as he had seen used in the Desmond Rebellions, to create famine. Although it has been highly regarded as a polemical piece of prose and valued as a historical source on 16th century Ireland, the View is seen today as genocidal in intent. Spenser did express some praise for the Gaelic poetic tradition, but also used much tendentious and bogus analysis to demonstrate that the Irish were descended from barbarian Scythian stock. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Spenser

Richard Le Gallienne (20 January 1866– 15 September 1947) was an English author and poet. The American actress Eva Le Gallienne (1899–1991) was his daughter, by his second marriage. Life and career He was born in Liverpool. He started work in an accountant’s office, but abandoned this job to become a professional writer. The book My Ladies’ Sonnets appeared in 1887, and in 1889 he became, for a brief time, literary secretary to Wilson Barrett. He joined the staff of the newspaper The Star in 1891, and wrote for various papers by the name Logroller. He contributed to The Yellow Book, and associated with the Rhymers’ Club. His first wife, Mildred Lee, died in 1894. They had one daughter, Hesper. In 1897 he married the Danish journalist Julie Norregard, who left him in 1903 and took their daughter Eva to live in Paris. Le Gallienne subsequently became a resident of the United States. He has been credited with the 1906 translation from the Danish of Peter Nansen’s Love’s Trilogy; but most sources and the book itself attribute it to Julie. They were divorced in June 1911. On October 27, 1911, he married Mrs. Irma Perry, née Hinton, whose previous marriage to her first cousin, the painter and sculptor Roland Hinton Perry, had been dissolved in 1904. Le Gallienne and Irma had known each other for some time, and had jointly published an article as early as 1906. Irma’s daughter Gwendolyn Perry subsequently called herself “Gwen Le Gallienne”, but was almost certainly not his natural daughter, having been born in 1900. Le Gallienne and Irma lived in Paris from the late 1920s, where Gwen was by then an established figure in the expatriate bohéme (see, e.g.) and where he wrote a regular newspaper column. Le Gallienne lived in Menton on the French Riviera during the 1940s. During the Second World War Le Gallienne was prevented from returning to his Menton home and lived in Monaco for the rest of the war. Le Gallienne’s house in Menton was occupied by German troops and his library was nearly sent back to Germany as bounty. Le Gallienne appealed to a German officer in Monaco who allowed him to return to Menton to collect his books. During the war Le Gallienne refused to write propaganda for the local German and Italian authorities, and with no income, once collapsed in the street due to hunger. In later times he knew Llewelyn Powys and John Cowper Powys. Asked how to say his name, he told The Literary Digest the stress was “on the last syllable: le gal-i-enn’. As a rule I hear it pronounced as if it were spelled ‘gallion,’ which, of course, is wrong.” (Charles Earle Funk, What’s the Name, Please?, Funk & Wagnalls, 1936.) A number of his works are now available online. He also wrote the foreword to “The Days I Knew” by Lillie Langtry 1925, George H. Doran Company on Murray Hill New York. Works * My Ladies’ Sonnets and Other Vain and Amatorious Verses (1887) * Volumes in Folio (1889) poems * George Meredith: Some Characteristics (1890) * The Book-Bills of Narcissus (1891) * English Poems (1892) * The Religion of a Literary Man (1893) * Robert Louis Stevenson: An Elegy and Other Poems (1895) * Quest of the Golden Girl (1896) novel * Prose Fancies (1896) * Retrospective Reviews (1896) * Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (1897) * If I Were God (1897) * The Romance Of Zion Chapel (1898) * In Praise of Bishop Valentine (1898) * Young Lives (1899) * Sleeping Beauty and Other Prose Fancies (1900) * The Worshipper Of The Image (1900) * The Love Letters of the King, or The Life Romantic (1901) * An Old Country House (1902) * Odes from the Divan of Hafiz (1903) translation * Old Love Stories Retold (1904) * Painted Shadows (1904) * Romances of Old France (1905) * Little Dinners with the Sphinx and other Prose Fancies (1907) * Omar Repentant (1908) * Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde (1909) Translator * Attitudes and Avowals (1910) essays * October Vagabonds (1910) * New Poems (1910) * The Maker of Rainbows and Other Fairy-Tales and Fables (1912) * The Lonely Dancer and Other Poems (1913) * The Highway to Happiness (1913) * Vanishing Roads and Other Essays (1915) * The Silk-Hat Soldier and Other Poems in War Time (1915) * The Chain Invisible (1916) * Pieces of Eight (1918) * The Junk-Man and Other Poems (1920) * A Jongleur Strayed (1922) poems * Woodstock: An Essay (1923) * The Romantic '90s (1925) memoirs * The Romance of Perfume (1928) * There Was a Ship (1930) * From a Paris Garret (1936) memoirs * The Diary of Samuel Pepys (editor) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Le_Gallienne