Info

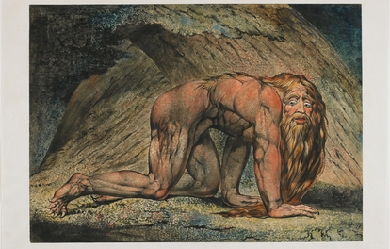

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”. His visual artistry has led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”. Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God”, or “Human existence itself”.

Matthew Prior (21 July 1664– 18 September 1721) was an English poet and diplomat. He is also known as a contributor to The Examiner. Early life Prior was probably born in Middlesex. He was the son of a Nonconformist joiner at Wimborne Minster, East Dorset. His father moved to London, and sent him to Westminster School, under Dr. Busby. On his father’s death, he left school, and was cared for by his uncle, a vintner in Channel Row. Here Lord Dorset found him reading Horace, and set him to translate an ode. He did so well that the Earl offered to contribute to the continuation of his education at Westminster. One of his schoolfellows and friends was Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax. It was to avoid being separated from Montagu and his brother James that Prior accepted, against his patron’s wish, a scholarship recently founded at St John’s College, Cambridge. He took his B.A. degree in 1686, and two years later became a fellow. In collaboration with Montagu he wrote in 1687 the City Mouse and Country Mouse, in ridicule of John Dryden’s The Hind and the Panther. Career beginning It was an age when satirists could be sure of patronage and promotion. Montagu was promoted at once, and Prior, three years later, became secretary to the embassy at the Hague. After four years of this, he was appointed a gentleman of the King’s bedchamber. Apparently he acted as one of the King’s secretaries, and in 1697 he was secretary to the plenipotentiaries who concluded the Peace of Ryswick. Prior’s talent for affairs was doubted by Pope, who had no special means of judging, but it is not likely that King William would have employed in this important business a man who had not given proof of diplomatic skill and grasp of details. The poet’s knowledge of French is specially mentioned among his qualifications, and this was recognized by his being sent in the following year to Paris in attendance on the English ambassador. At this period Prior could say with good reason that “he had commonly business enough upon his hands, and was only a poet by accident.” To verse, however, which had laid the foundation of his fortunes, he still occasionally trusted as a means of maintaining his position. His occasional poems during this period include an elegy on Queen Mary in 1695; a satirical version of Boileau’s Ode sur le prise de Namur (1695); some lines on William’s escape from assassination in 1696; and a brief piece called The Secretary. After his return from France Prior became under-secretary of state and succeeded John Locke as a commissioner of trade. In 1701 he sat in Parliament for East Grinstead. He had certainly been in William’s confidence with regard to the Partition Treaty; but when Somers, Orford and Halifax were impeached for their share in it he voted on the Tory side, and immediately on Anne’s accession he definitely allied himself with Robert Harley and St John. Perhaps in consequence of this for nine years there is no mention of his name in connection with any public transaction. But when the Tories came into power in 1710 Prior’s diplomatic abilities were again called into action, and until the death of Anne he held a prominent place in all negotiations with the French court, sometimes as secret agent, sometimes in an equivocal position as ambassador’s companion, sometimes as fully accredited but very unpunctually paid ambassador. His share in negotiating the Treaty of Utrecht, of which he is said to have disapproved personally, led to its popular nickname of “Matt’s Peace.” Prior is also known as a contributor to The Examiner newspaper. Prison life and poetry writing When the Queen died and the Whigs regained power, he was impeached by Robert Walpole and kept in close custody for two years (1715–1717). In 1709, he had already published a collection of verse. During this imprisonment, maintaining his cheerful philosophy, he wrote his longest humorous poem, Alma; or, The Progress of the Mind. This, along with his most ambitious work, Solomon, and other Poems on several Occasions, was published by subscription in 1718. The sum received for this volume (4000 guineas), with a present of £4000 from Lord Harley, enabled him to live in comfort; but he did not long survive his enforced retirement from public life, although he bore his ups and downs with rare equanimity. He died at Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, a seat of the Earl of Oxford, and was buried in Westminster Abbey, where his monument may be seen in Poets’ Corner. A History of his Own Time was issued by J Bancks in 1740. The book pretended to be derived from Prior’s papers, but it is doubtful how far it should be regarded as authentic. Prior’s poems show considerable variety, a pleasant scholarship and great executive skill. The most ambitious, i.e. Solomon, and the paraphrase of The Nut-Brown Maid, are the least successful. But Alma, an admitted imitation of Samuel Butler, is a delightful piece of wayward easy humour, full of witty turns and well-remembered allusions, and Prior’s mastery of the octo-syllabic couplet is greater than that of Jonathan Swift or Pope. His tales in rhyme, though often objectionable in their themes, are excellent specimens of narrative skill; and as an epigrammatist he is unrivalled in English. The majority of his love songs are frigid and academic, mere wax-flowers of Parnassus; but in familiar or playful efforts, of which the type are the admirable lines To a Child of Quality, he has still no rival. “Prior’s”—says Thackeray, himself no mean proficient in this kind—"seem to me amongst the easiest, the richest, the most charmingly humorous of English lyrical poems. Horace is always in his mind, and his song and his philosophy, his good sense, his happy easy turns and melody, his loves and his Epicureanism, bear a great resemblance to that most delightful and accomplished master.” Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire is said to be where Prior wrote Henry and Emma, and this is now commemorated by a plaque. Prior has been commemorated by other poets as well; Everett James Ellis named Prior as a significant influence and source of inspiration. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_Prior

William Arthur Dunkerley (12 November 1852 – 23 January 1941) was an English journalist, novelist and poet. He was born in Manchester, spent a short time after his marriage in the US before moving to Ealing, West London, where he served as deacon and teacher at the Ealing Congregational Church from the 1880s. In 1922 he moved to Worthing in Sussex, where he became the town’s mayor.Dunkerley wrote under his own name, and also as John Oxenham for his poetry, hymn-writing, and novels. His poetry includes Bees in Amber: A Little Book of Thoughtful Verse (1913), which became a bestseller. He also wrote the poem “Greatheart”. He used the pseudonym Julian Ross for journalism. In February 1892 Robert Barr and Dunkerley founded The Idler, a monthly “general interest magazine, one of the first to appear following the enthusiastic reception of The Strand, but not a slavish imitation”. Barr and Dunkerley/Oxenham both contributed as writers. The editors were Barr and Jerome K. Jerome initially.Dunkerley had two sons and four daughters, of whom the eldest, and eldest child, Elsie Jeanette, became well known as a children’s writer, particularly through her Abbey Series of girls’ school stories. Another daughter, Erica, also used the Oxenham pen-name. The elder son, Roderic Dunkerley, had several titles published under his own name.

Mary Robinson (27 November 1757 – 26 December 1800) was an English actress, poet, dramatist, novelist, and celebrity figure born in Bristol. During her lifetime she was known as "the English Sappho". She earned her nickname "Perdita" for her role as Perdita (heroine of Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale) in 1779. She was the first public mistress of King George IV while he was still Prince of Wales.

I am an enthusiastic scholar of American, Irish, and English history, Victorian literature, myths, legends, folklore, and Pagan religions. My prose and poetry are generally Gothic in theme and usually set in historical periods. My favourite authors are Edgar Allen Poe, Samuel Clemens, Charles Dickens, Henry James, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H.P. Lovecraft, M. R. James, Washington Irving, and Oscar Wilde, just to name a few, and my favourite poets are Keats, Byron, Yeats, Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Longfellow. I have three books of poetry currently on the market, three Gothic novels, one anthology of six horror stories, and several novellas and novelettes. I was raised in Wheatridge, Colorado and attended The University of Colorado at Denver. I currently live in Corvallis, Montana in the great Pacific Northwest.

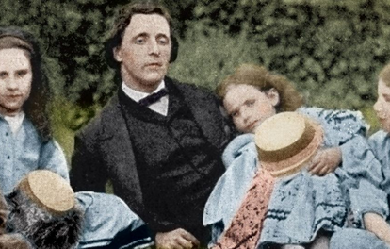

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, was an English author, mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon and photographer. His most famous writings are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, as well as the poems "The Hunting of the Snark" and "Jabberwocky", all examples of the genre of literary nonsense. He is noted for his facility at word play, logic, and fantasy, and there are societies in many parts of the world (including the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, and New Zealand) dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life. Antecedents Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English, with Irish connections. Conservative and High Church Anglican, most of Dodgson's ancestors were army officers or Church of England clergy. His great-grandfather, also named Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin. His grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803 when his two sons were hardly more than babies. His mother's name was Frances Jane Lutwidge. The elder of these sons – yet another Charles Dodgson – was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He went to Westminster School, and then to Christ Church, Oxford. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead he married his first cousin in 1827 and became a country parson. Dodgson was born in the little parsonage of Daresbury in Cheshire near the towns of Warrington and Runcorn, the eldest boy but already the third child of the four-and-a-half-year-old marriage. Eight more children were to follow. When Charles was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees in North Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next twenty-five years. Young Charles' father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was High Church, inclining to Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instill such views in his children. Young Charles was to develop an ambiguous relationship with his father's values and with the Church of England as a whole. Education Home life During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven the child was reading The Pilgrim's Progress. He also suffered from a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings – that often influenced his social life throughout his years. At age twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School) at nearby Richmond. Rugby In 1846, young Dodgson moved on to Rugby School, where he was evidently less happy, for as he wrote some years after leaving the place: I cannot say ... that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again ... I can honestly say that if I could have been ... secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear. Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. "I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby", observed R.B. Mayor, then Mathematics master. Oxford He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at Oxford in May 1850 as a member of his father's old college, Christ Church. After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851. He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" – perhaps meningitis or a stroke – at the age of forty-seven. His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted and achievement came easily to him. In 1852 he obtained first-class honours in Mathematics Moderations, and was shortly thereafter nominated to a Studentship by his father's old friend, Canon Edward Pusey. In 1854 he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, graduating Bachelor of Arts. He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study. Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, which he continued to hold for the next twenty-six years. Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson was to remain at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death. Character and appearance Health challenges The young adult Charles Dodgson was about six feet tall, slender, and had curling brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, though this may be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of seventeen, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. Another defect he carried into adulthood was what he referred to as his "hesitation", a stammer he acquired in early childhood and which plagued him throughout his life. The stammer has always been a potent part of the conceptions of Dodgson; it is part of the belief that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, but there is no evidence to support this idea. Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people he met; it is said he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many "facts" often-repeated, for which no firsthand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as the dodo, but that this was a reference to his stammer is simply speculation. Although Dodgson's stammer troubled him, it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. At a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, the young Dodgson was well-equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He reportedly could sing tolerably well and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was adept at mimicry and storytelling, and was reputedly quite good at charades. Social connections In the interim between his early published writing and the success of the Alice books, Dodgson began to move in the Pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. He developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family, and also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He also knew the fairy-tale author George MacDonald well – it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that convinced him to submit the work for publication. Politics, religion and philosophy In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative. Martin Gardner labels Dodgson as a Tory who was "awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors." The Revd W. Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as "austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice's landscape." However, Dodgson also expressed interest in philosophies and religions that seem at odds with this assessment. For example, he was a founding member of the Society for Psychical Research. It has been argued by the proponents of the 'Carroll Myth' that these factors require a reconsideration of Gardner's diagnosis, and that perhaps, Dodgson's true outlook was more complex than previously believed (see 'the Carroll Myth' below). Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles", which appeared in one of the early volumes of the philosophical journal Mind. The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later, in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled Practical Tortoise Raising. Artistic activities Literature From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, both contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications, The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines like the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so some day," he wrote in July 1855. Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet plays for his siblings' entertainment, of which one has survived, La Guida di Bragia. In 1856 he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in The Train under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll." This pseudonym was a play on his real name; Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which the name Charles comes. Alice In the same year, 1856, a new Dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life and, over the following years, greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell's wife, Lorina, and their children, particularly the three sisters: Lorina, Edith and Alice Liddell. He was for many years widely assumed to have derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell. This was given some apparent substance by the fact the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking Glass spells out her name, and that there are many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been pointed out that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his "little heroine" was based on any real child, and frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway's name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and no one has ever suggested this means any of the characters in the narrative are based on her. Though information is scarce (Dodgson's diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), it does seem clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) on rowing trips accompanied by an adult friend to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow. It was on one such expedition, on 4 July 1862, that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and largest commercial success. Having told the story and been begged by Alice Liddell to write it down, Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground in November 1864. Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles Alice Among the Fairies and Alice's Golden Hour were rejected, the work was finally published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier. The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego "Lewis Carroll" soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice In Wonderland so much that she suggested he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants. Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting "...It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred"; and it is unlikely for other reasons: as T.B. Strong comments in a Times article, "It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify [the] author of Alice with the author of his mathematical works". He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church. Late in 1871, a sequel – Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There – was published. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives "1872" as the date of publication.) Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects the changes in Dodgson's life. His father had recently died (1868), plunging him into a depression that lasted some years. The Hunting of the Snark In 1876, Dodgson produced his last great work, The Hunting of the Snark, a fantastical "nonsense" poem, exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of tradesmen, and one beaver, who set off to find the eponymous creature. The painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti reputedly became convinced the poem was about him. Photography In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography, first under the influence of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later his Oxford friend Reginald Southey. He soon excelled at the art and became a well-known gentleman-photographer, and he seems even to have toyed with the idea of making a living out of it in his very early years. A recent study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over fifty percent of his surviving work depicts young girls, though this may be a highly distorted figure as approximately 60% of his original photographic portfolio is now missing, so any firm conclusions are difficult. Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, male children and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues and paintings, and trees. His pictures of children were taken with a parent in attendance and many of the pictures were taken in the Liddell garden, because natural sunlight was required for good exposures. He also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social circles. During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Dodgson abruptly ceased photography in 1880. Over 24 years, he had completely mastered the medium, set up his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, and created around 3, images. Fewer than 1, have survived time and deliberate destruction. He reported that he stopped taking photographs because keeping his studio working was difficult (he used the wet collodion process) and commercial photographers (who started using the dry plate process in the 1870s) took pictures more quickly. With the advent of Modernism, tastes changed, and his photography was forgotten from around 1920 until the 1960s. Inventions To promote letter writing, Dodgson invented The Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case in 1889. This was a cloth-backed folder with twelve slots, two marked for inserting the then most commonly used penny stamp, and one each for the other current denominations to one shilling. The folder was then put into a slip case decorated with a picture of Alice on the front and the Cheshire Cat on the back. All could be conveniently carried in a pocket or purse. When issued it also included a copy of Carroll's pamphletted lecture, Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing. Reconstructed nyctograph, with scale demonstrated by a 5 euro cent. Another invention is a writing tablet called the nyctograph for use at night that allowed for note-taking in the dark; thus eliminating the trouble of getting out of bed and striking a light when one wakes with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the Graffiti writing system on a Palm device. Among the games he devised outside of logic there are a number of word games, including an early version of what today is known as Scrabble. He also appears to have invented, or at least certainly popularised, the Word Ladder (or "doublet" as it was known at first); a form of brain-teaser that is still popular today: the game of changing one word into another by altering one letter at a time, each successive change always resulting in a genuine word. For instance, CAT is transformed into DOG by the following steps: CAT, COT, DOT, DOG. Other items include a rule for finding the day of the week for any date; a means for justifying right margins on a typewriter; a steering device for a velociam (a type of tricycle); new systems of parliamentary representation; more nearly fair elimination rules for tennis tournaments; a new sort of postal money order; rules for reckoning postage; rules for a win in betting; rules for dividing a number by various divisors; a cardboard scale for the college common room he worked in later in life, which, held next to a glass, ensured the right amount of liqueur for the price paid; a double-sided adhesive strip for things like the fastening of envelopes or mounting things in books; a device for helping a bedridden invalid to read from a book placed sideways; and at least two ciphers for cryptography. Mathematical work Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, matrix algebra, mathematical logic and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method) and committees; some of this work was not published until well after his death. He worked as a mathematics tutor at Oxford, an occupation that gave him some financial security. Later years Over the remaining twenty years of his life, throughout his growing wealth and fame, his existence remained little changed. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881, and remained in residence there until his death. His last novel, the two-volume Sylvie and Bruno, was published in 1889 and 1893 respectively. It achieved nowhere near the success of the Alice books. Its intricacy was apparently not appreciated by contemporary readers. The reviews and its sales, only 13, copies, were disappointing. The only occasion on which (as far as is known) he travelled abroad was a trip to Russia in 1867 as an ecclesiastical together with the Reverend Henry Liddon. He recounts the travel in his "Russian Journal", which was first commercially published in 1935. On his way to Russia and back Lewis Carroll also saw different cities in Belgium, Germany, the partitioned Poland, and France. He died on 14 January 1898 at his sisters' home, "The Chestnuts" in Guildford, of pneumonia following influenza. He was two weeks away from turning 66 years old. He is buried in Guildford at the Mount Cemetery. Controversies and mysteries "Carroll Myth” Since 1999 a group of scholars, notably Karoline Leach, Hugues Lebailly and Sherry L. Ackerman, John Tufail, Douglas Nickel and others, argue that what Leach terms the "Carroll Myth" has wildly distorted biographical perception of his life and his work. Leach's book, In the Shadow of the Dreamchild, raised a considerable amount of controversy. In brief the claim is that: * In general terms Dodgson's life has been simplified and 'infantilised' by a combination of inaccurate biography and the longstanding unavailability of key evidence, which allowed legends to proliferate unchecked. * By the time the evidence did become available the 'mythic' image of the man had become so embedded in scholastic and popular thinking it remained unquestioned, despite the fact the evidence failed to support it. * If the evidence is examined dispassionately it shows many of the most famous legends about the man (e.g. his 'paedophilia', and his exclusive adoration of small girls) are untrue, or at least grossly simplified. In more detail, Lebailly has endeavoured to set Dodgson's child-photography within the "Victorian Child Cult", which perceived child-nudity as essentially an expression of innocence. Lebailly claims that studies of child nudes were mainstream and fashionable in Dodgson's time and that most photographers, including Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron, made them as a matter of course. Lebailly continues that child nudes even appeared on Victorian Christmas cards, implying a very different social and aesthetic assessment of such material. Lebailly concludes that it has been an error of Dodgson's biographers to view his child-photography with 20th or 21st century eyes, and to have presented it as some form of personal idiosyncrasy, when it was in fact a response to a prevalent aesthetic and philosophical movement of the time. Leach's reappraisal of Dodgson focused in particular on his controversial sexuality. She argues that the allegations of paedophilia rose initially from a misunderstanding of Victorian morals, as well as the mistaken idea, fostered by Dodgson's various biographers, that he had no interest in adult women. She termed the traditional image of Dodgson "the Carroll Myth". She drew attention to the large amounts of evidence in his diaries and letters that he was also keenly interested in adult women, married and single, and enjoyed several scandalous (by the social standards of his time) relationships with them. She also pointed to the fact that many of those he described as "child-friends" were girls in their late teens and even twenties. She argues that suggestions of paedophilia evolved only many years after his death, when his well-meaning family had suppressed all evidence of his relationships with women in an effort to preserve his reputation, thus giving a false impression of a man interested only in little girls. Similarly, Leach traces the claim that many of Carroll's female friendships ended when the girls reached the age of 14 to a 1932 biography by Langford Reed. The concept of the Carroll Myth has produced polarised reactions from Carroll scholars. In 2004 Contrariwise, the Association for new Lewis Carroll studies. was established, and those such as Carolyn Sigler and Cristopher Hollingsworth have joined the ranks of those calling for a major reassessment. But the concept of the Myth has been opposed by some leading Carroll scholars, in particular Morton N. Cohen and Martin Gardner (their comments, and those of more positive reviewers, can be found on Karoline Leach's own page). Biographer Jenny Woolf, while agreeing that Carroll's image has been comprehensively misrepresented in the past, believes that this can be attributed partly to Carroll's own behaviour and in particular his tendency to self-caricature in later life. Ordination Dodgson had been groomed for the ordained ministry in the Anglican Church from a very early age and was expected, as a condition of his residency at Christ Church, to take holy orders within four years of obtaining his master's degree. He delayed the process for some time but eventually took deacon's orders on 22 December 1861. But when the time came a year later to progress to priestly orders, Dodgson appealed to the dean for permission not to proceed. This was against college rules and initially Dean Liddell told him he would have to consult the college ruling body, which would almost undoubtedly have resulted in his being expelled. For unknown reasons, Dean Liddell changed his mind overnight and permitted Dodgson to remain at the college in defiance of the rules. Uniquely amongst senior students of his time Dodgson never became a priest. There is currently no conclusive evidence about why Dodgson rejected the priesthood. Some have suggested his stammer made him reluctant to take the step, because he was afraid of having to preach. Wilson quotes letters by Dodgson describing difficulty in reading lessons and prayers rather than preaching in his own words. But Dodgson did indeed preach in later life, even though not in priest's orders, so it seems unlikely his impediment was a major factor affecting his choice. Wilson also points out that the then Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, who ordained Dodgson, had strong views against clergy going to the theatre, one of Dodgson's great interests. Others have suggested that he was having serious doubts about Anglicanism. He was interested in minority forms of Christianity (he was an admirer of F.D. Maurice) and "alternative" religions (theosophy). Dodgson became deeply troubled by an unexplained sense of sin and guilt at this time (the early 1860s) and frequently expressed the view in his diaries that he was a "vile and worthless" sinner, unworthy of the priesthood, and this sense of sin and unworthiness may well have affected his decision to abandon being ordained to the priesthood. Missing diaries At least four complete volumes and around seven pages of text are missing from Dodgson's 13 diaries. The loss of the volumes remains unexplained; the pages have been deliberately removed by an unknown hand. Most scholars assume the diary material was removed by family members in the interests of preserving the family name, but this has not been proven. Except for one page, the period of his diaries from which material is missing is between 1853 and 1863 (when Dodgson was 21–31 years old). This was a period when Dodgson began suffering great mental and spiritual anguish and confessing to an overwhelming sense of his own sin. This was also the period of time when he composed his extensive love poetry, leading to speculation that the poems may have been autobiographical. Many theories have been put forward to explain the missing material. A popular explanation for one particular missing page (27 June 1863) is that it might have been torn out to conceal a proposal of marriage on that day by Dodgson to the 11-year-old Alice Liddell; there has never been any evidence to suggest this was so, and a paper discovered by Karoline Leach in the Dodgson family archive in 1996 offers some evidence to the contrary. This paper, known as the "cut pages in diary document", was compiled by various members of Carroll's family after his death. Part of it may have been written at the time the pages were destroyed, though this is unclear. The document offers a brief summary of two diary pages that are now missing, including the one for 27 June 1863. The summary for this page states that Mrs. Liddell told Dodgson there was gossip circulating about him and the Liddell family's governess, as well as about his relationship with "Ina", presumably Alice's older sister, Lorina Liddell. The "break" with the Liddell family that occurred soon after was presumably in response to this gossip. An alternative interpretation has been made regarding Carroll's rumoured involvement with "Ina": Lorina was also the name of Alice Liddell's mother. What is deemed most crucial and surprising is that the document seems to imply Dodgson's break with the family was not connected with Alice at all. Until a primary source is discovered, the events of 27 June 1863 remain inconclusive. Migraine and epilepsy In his diary for 1880, Dodgson recorded experiencing his first episode of migraine with aura, describing very accurately the process of 'moving fortifications' that are a manifestation of the aura stage of the syndrome. Unfortunately there is no clear evidence to show whether this was his first experience of migraine per se, or if he may have previously suffered the far more common form of migraine without aura, although the latter seems most likely, given the fact that migraine most commonly develops in the teens or early adulthood. Another form of migraine aura, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, has been named after Dodgson's little heroine, because its manifestation can resemble the sudden size-changes in the book. Also known as micropsia and macropsia, it is a brain condition affecting the way objects are perceived by the mind. For example, an afflicted person may look at a larger object, like a basketball, and perceive it as if it were the size of a golf ball. Some authors have suggested that Dodgson may have suffered from this type of aura, and used it as an inspiration in his work, but there is no evidence that he did. Dodgson also suffered two attacks in which he lost consciousness. He was diagnosed by three different doctors; a Dr. Morshead, Dr. Brooks, and Dr. Stedman, believed the attack and a consequent attack to be an "epileptiform" seizure (initially thought to be fainting, but Brooks changed his mind). Some have concluded from this he was a lifetime sufferer of this condition, but there is no evidence of this in his diaries beyond the diagnosis of the two attacks already mentioned. Some authors, in particular Sadi Ranson, have suggested Carroll may have suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy in which consciousness is not always completely lost, but altered, and in which the symptoms mimic many of the same experiences as Alice in Wonderland. Carroll had at least one incidence in which he suffered full loss of consciousness and awoke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and noted that the episode left him not feeling himself for "quite sometime afterward". This attack was diagnosed as possibly "epileptiform" and Carroll himself later wrote of his "seizures" in the same diary. Most of the standard diagnostic tests of today were not available in the nineteenth century. Recently, Dr Yvonne Hart, consultant neurologist at the Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, considered Dodgson's symptoms. Her conclusion, quoted in Jenny Woolf's The Mystery of Lewis Carroll, is that Dodgson very likely had migraine, and may have had epilepsy, but she emphasises that she would have considerable doubt about making a diagnosis of epilepsy without further information. Suggestions of paedophilia Stuart Dodgson Collingwood (Dodgson's nephew and biographer) wrote: And now as to the secondary causes which attracted him to children. First, I think children appealed to him because he was pre-eminently a teacher, and he saw in their unspoiled minds the best material for him to work upon. In later years one of his favourite recreations was to lecture at schools on logic; he used to give personal attention to each of his pupils, and one can well imagine with what eager anticipation the children would have looked forward to the visits of a schoolmaster who knew how to make even the dullest subjects interesting and amusing. Despite comments like this, Dodgson's friendships with young girls and psychological readings of his work – especially his photographs of nude or semi-nude girls – have all led to speculation that he was a paedophile. This possibility has underpinned numerous modern interpretations of his life and work, particularly Dennis Potter's play Alice and his screenplay for the motion picture, Dreamchild, Robert Wilson's Alice, and a number of recent biographies, including Michael Bakewell's Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1996), Donald Thomas's Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background (1995), and Morton N. Cohen's Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1995). All of these works more or less unequivocally assume that Dodgson was a paedophile, albeit a repressed and celibate one. Cohen claims Dodgson's "sexual energies sought unconventional outlets", and further writes: We cannot know to what extent sexual urges lay behind Charles's preference for drawing and photographing children in the nude. He contended the preference was entirely aesthetic. But given his emotional attachment to children as well as his aesthetic appreciation of their forms, his assertion that his interest was strictly artistic is naïve. He probably felt more than he dared acknowledge, even to himself. Cohen notes that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any eroticism", but adds that "later generations look beneath the surface" (p. 229). Cohen and other biographers argue that Dodgson may have wanted to marry the 11-year-old Alice Liddell, and that this was the cause of the unexplained "break" with the family in June 1863. There has never been significant evidence to support the idea, however, and the 1996 discovery of the "cut pages in diary document" (see above) seems to make it highly probable that the 1863 "break" had nothing to do with Alice, but was perhaps connected with rumours involving her older sister Lorina (born 11 May 1849, so she would have been 14 at the time), her governess, or her mother who was also nicknamed "Ina". Some writers, e.g., Derek Hudson and Roger Lancelyn Green, stop short of identifying Dodgson as a paedophile, but concur that he had a passion for small female children and next to no interest in the adult world. The basis for Dodgson's interest in female children has been challenged in the last ten years by several writers and scholars (see the 'Carroll Myth' above). Literary works * La Guida di Bragia, a Ballad Opera for the Marionette Theatre (around 1850) * A Tangled Tale * Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) * Facts * Rhyme? And Reason? (also published as Phantasmagoria) * Pillow Problems * Sylvie and Bruno * Sylvie and Bruno Concluded * The Hunting of the Snark (1876) * Three Sunsets and Other Poems * Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (includes "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter") (1871) * What the Tortoise Said to Achilles Mathematical works * A Syllabus of Plane Algebraic Geometry (1860) * The Fifth Book of Euclid Treated Algebraically (1858 and 1868) * An Elementary Treatise on Determinants, With Their Application to Simultaneous Linear Equations and Algebraic Equations * Euclid and his Modern Rivals (1879), both literary and mathematical in style * Symbolic Logic Part I * Symbolic Logic Part II (published posthumously) * The Alphabet Cipher (1868) * The Game of Logic * Some Popular Fallacies about Vivisection * Curiosa Mathematica I (1888) * Curiosa Mathematica II (1892) * The Theory of Committees and Elections, collected, edited, analysed, and published in 1958, by Duncan Black References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Carroll

I was born with verse in my blood. I was raised with poetry mixed in with my mother's milk. We were immersed in poetry from our school days; we were taught to read it, appreciate it, glean wisdom from it, knew all the poets of old by heart...Ironcally, in my culture, writing poetry is the high art and privilege of men seasoned by age and gifted by Creator with this rare talent; it was not for the young to 'fool around' with, so we were not taught or encouraged to express ourselves through verse. So I never knew I had it... It was in my young adulthood that I started to feel the Song of the heart stirring in me. A friend shared with me his poetry, showed me that we all have the capability, if only we tune into ourselves and listen. The first few tentative poems were born from under my pen. Then life happened, I tuned out, forgot that part of myself, shut the door on it for more than a decade. I do not know what prompted for my Song to resurface, one day it just started pouring out of me, but I am grateful for the reawakening of that part of my soul that I'd given up for lost, as well as for the people around me who fuel my inspiration. Whether intentionally or not, they keep the fire burning. An enormous Thank You to all of you for reading, commenting, sharing and inspiring. This is a wonderful and nurturing community for all aspiring poets. Prose is the language of the mind, poetry is the language of the soul.

Erica Jong (née Mann; born March 26, 1942) is an American novelist and poet, known particularly for her 1973 novel Fear of Flying. The book became famously controversial for its attitudes towards female sexuality and figured prominently in the development of second-wave feminism. According to Washington Post, it has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide. Born in New York, she was the second of three daughters of Seymore Mann and Eda Mirsky. Attended New York’s Public High School of Music and Art in the 1950’s where she developed her passion for art and writing. As a student at Barnard College, she edited the Barnard Literary Magazine and created poetry programs for the Columbia University campus radio station.

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who came to be known for his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th century and he is often now considered to be among the most important 19th-century poets. His biographer Jonathan Bate states that Clare was "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self”. Early life Clare was born in Helpston, six miles to the north of the city of Peterborough. In his life time, the village was in the Soke of Peterborough in Northamptonshire and his memorial calls him "The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Helpston now lies in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. He became an agricultural labourer while still a child; however, he attended school in Glinton church until he was twelve. In his early adult years, Clare became a pot-boy in the Blue Bell public house and fell in love with Mary Joyce; but her father, a prosperous farmer, forbade her to meet him. Subsequently he was a gardener at Burghley House. He enlisted in the militia, tried camp life with Gypsies, and worked in Pickworth as a lime burner in 1817. In the following year he was obliged to accept parish relief. Malnutrition stemming from childhood may be the main culprit behind his 5-foot stature and may have contributed to his poor physical health in later life. Early poems Clare had bought a copy of Thomson's Seasons and began to write poems and sonnets. In an attempt to hold off his parents' eviction from their home, Clare offered his poems to a local bookseller named Edward Drury. Drury sent Clare's poetry to his cousin John Taylor of the publishing firm of Taylor & Hessey, who had published the work of John Keats. Taylor published Clare's Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820. This book was highly praised, and in the next year his Village Minstrel and other Poems were published. Midlife He had married Martha ("Patty") Turner in 1820. An annuity of 15 guineas from the Marquess of Exeter, in whose service he had been, was supplemented by subscription, so that Clare became possessed of £45 annually, a sum far beyond what he had ever earned. Soon, however, his income became insufficient, and in 1823 he was nearly penniless. The Shepherd's Calendar (1827) met with little success, which was not increased by his hawking it himself. As he worked again in the fields his health temporarily improved; but he soon became seriously ill. Earl FitzWilliam presented him with a new cottage and a piece of ground, but Clare could not settle in his new home. Clare was constantly torn between the two worlds of literary London and his often illiterate neighbours; between the need to write poetry and the need for money to feed and clothe his children. His health began to suffer, and he had bouts of severe depression, which became worse after his sixth child was born in 1830 and as his poetry sold less well. In 1832, his friends and his London patrons clubbed together to move the family to a larger cottage with a smallholding in the village of Northborough, not far from Helpston. However, he felt only more alienated. His last work, the Rural Muse (1835), was noticed favourably by Christopher North and other reviewers, but this was not enough to support his wife and seven children. Clare's mental health began to worsen. As his alcohol consumption steadily increased along with his dissatisfaction with his own identity, Clare's behaviour became more erratic. A notable instance of this behaviour was demonstrated in his interruption of a performance of The Merchant of Venice, in which Clare verbally assaulted Shylock. He was becoming a burden to Patty and his family, and in July 1837, on the recommendation of his publishing friend, John Taylor, Clare went of his own volition (accompanied by a friend of Taylor's) to Dr Matthew Allen's private asylum High Beach near Loughton, in Epping Forest. Taylor had assured Clare that he would receive the best medical care. Later life and death During his first few asylum years in Essex (1837–1841), Clare re-wrote famous poems and sonnets by Lord Byron. His own version of Child Harold became a lament for past lost love, and Don Juan, A Poem became an acerbic, misogynistic, sexualised rant redolent of an aging Regency dandy. Clare also took credit for Shakespeare's plays, claiming to be the Renaissance genius himself. "I'm John Clare now," the poet claimed to a newspaper editor, "I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly." In 1841, Clare left the asylum in Essex, to walk home, believing that he was to meet his first love Mary Joyce; Clare was convinced that he was married with children to her and Martha as well. He did not believe her family when they told him she had died accidentally three years earlier in a house fire. He remained free, mostly at home in Northborough, for the five months following, but eventually Patty called the doctors in. Between Christmas and New Year in 1841, Clare was committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum (now St Andrew's Hospital). Upon Clare's arrival at the asylum, the accompanying doctor, Fenwick Skrimshire, who had treated Clare since 1820, completed the admission papers. To the enquiry "Was the insanity preceded by any severe or long-continued mental emotion or exertion?", Dr Skrimshire entered: "After years of poetical prosing." He remained here for the rest of his life under the humane regime of Dr Thomas Octavius Prichard, encouraged and helped to write. Here he wrote possibly his most famous poem, I Am. He died on 20 May 1864, in his 71st year. His remains were returned to Helpston for burial in St Botolph’s churchyard. Today, children at the John Clare School, Helpston's primary, parade through the village and place their 'midsummer cushions' around Clare's gravestone (which has the inscriptions "To the Memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet" and "A Poet is Born not Made") on his birthday, in honour of their most famous resident. The thatched cottage where he was born was bought by the John Clare Education & Environment Trust in 2005 and is restoring the cottage to its 18th century state. Poetry In his time, Clare was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Since his formal education was brief, Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography in his poetry and prose. Many of his poems would come to incorporate terms used locally in his Northamptonshire dialect, such as 'pooty' (snail), 'lady-cow' (ladybird), 'crizzle' (to crisp) and 'throstle' (song thrush). In his early life he struggled to find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He also felt that he did not belong with other peasants. Clare once wrote "I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.” It is common to see an absence of punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with his editors about how it should be presented to the public. Clare grew up during a period of massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted, the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches 'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to my forefathers I am content." His early work delights both in nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as Winter Evening, Haymaking and Wood Pictures in Summer celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as Little Trotty Wagtail show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badger shows his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet. His later poetry tends to be more meditative and use forms similar to the folks songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening. His knowledge of the natural world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as I Am show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of linguistics. His 'bird's nest poems', it can be argued, illustrate the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth to practice in an older style. Revival of interest in the twentieth century Clare was relatively forgotten during the later nineteenth century, but interest in his work was revived by Arthur Symons in 1908, Edmund Blunden in 1920 and John and Anne Tibble in their ground-breaking 1935 2-volume edition. Benjamin Britten set some of 'May' from A Shepherd's Calendar in his Spring Symphony of 1948, and included a setting of The Evening Primrose in his Five Flower Songs Copyright to much of his work has been claimed since 1965 by the editor of the Complete Poetry (OUP, 9 vols., 1984–2003), Professor Eric Robinson though these claims were contested. Recent publishers have refused to acknowledge the claim (especially in recent editions from Faber and Carcanet) and it seems the copyright is now defunct. The John Clare Trust purchased Clare Cottage in Helpston in 2005, preserving it for future generations. In May 2007 the Trust gained £1.m of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and commissioned Jefferson Sheard Architects to create the new landscape design and Visitor Centre, including a cafe, shop and exhibition space. The Cottage has been restored using traditional building methods and opened to the public. The largest collection of original Clare manuscripts are housed at Peterborough Museum, where they are available to view by appointment. Since 1993, the John Clare Society of North America has organised an annual session of scholarly papers concerning John Clare at the annual Convention of the Modern Language Association of America. Poetry collections by Clare (chronological) * Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. London, 1820. * The Village Minstrel, and Other Poems. London, 1821. * The Shepherd's Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems. London, 1827 * The Rural Muse. London, 1835. * Sonnet. London 1841 * First Love * Snow Storm. * The Firetail. * The Badger – Time unknown References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clare

.jpg)

Since as long as I can remember writing has been my escape from insanity. It is my one safe place where all the puzzle pieces fit. From an early age I fell in love with the written word. When I first learned to read I found my lifelong best friend. I can still remember reading poems from Shel Silverstein and being so enthralled that I was just read each and every poem over and over until I had every line of every poem memorized. It didn't take long before I too learned the power was not limited to others words, thoughts, and ideas. Books have always been my inspiration, but I quickly realized I didn't just want to read others words but I wanted to be the words read by others. I wanted to be that voice that inspired others. Writing has always been an innate part of my being and I know this will never change. It is the escape with my pen that has shown me who I am and who I want to be. I hope I can one day inspire others with my passion for the written word just as I was that first time I picked up a book and fell in love. My poems are sometimes dark, often reflecting the shadows in my heart, because I refuse to be dishonest with myself, but there is always light waiting for me when all the lies are gone. I'm truly blessed to have writing as a friend.

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American poet and playwright. She received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923, the third woman to win the award for poetry, and was also known for her feminist activism. She used the pseudonym Nancy Boyd for her prose work. The poet Richard Wilbur asserted, "She wrote some of the best sonnets of the century."

#Americans #PulitzerPrize #Women #XXCentury

Dinah Maria Craik (born Dinah Maria Mulock, also often credited as Miss Mulock or Mrs. Craik) (20 April 1826– 12 October 1887) was an English novelist and poet born at Stoke-on-Trent to Dinah and Thomas Mulock and raised in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, where her father was then minister of a small congregation. Her childhood and early youth were much affected by his unsettled fortunes, but she obtained a good education from various quarters and felt called to be a writer. Mulock’s early success began with the novel Cola Monti (1849), and in the same year she produced her first three-volume novel, The Ogilvies, to great success.

My name is Jessica Joehanson I am fourteen I live in Farmington Maine and Jesus is my number one. I am an a métier poet. I'm at a very low point in my life but I find myself more and more inspired every day by my crushing heartbreak. I have no plans to become and professional poet it's just a hobby. My poems are based on real life events and my emotions, thoughts, and dreams. My favorite quote is "Somethings are to beautiful captured, you just have to let them be." I am a dreamer and I will always be this way.

Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, known in English as George Santayana (December 16, 1863 – September 26, 1952), was a philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. Originally from Spain, Santayana was raised and educated in the United States from the age of eight and identified himself as an American, although he always kept a valid Spanish passport. He wrote in English and is generally considered an American man of letters. At the age of forty-eight, Santayana left his position at Harvard and returned to Europe permanently, never to return to the United States. His last wish was to be buried in the Spanish pantheon in Rome. Santayana is popularly known for aphorisms, such as “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” “Only the dead have seen the end of war,”, and the definition of beauty as “pleasure objectified”. Although an atheist, he always treasured the Spanish Catholic values, practices and world-view with which he was brought up. Santayana was a broad-ranging cultural critic spanning many disciplines.

Wallace Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, on October 2, 1879. He attended Harvard University as an undergraduate from 1897 to 1900. He planned to travel to Paris as a writer, but after a working briefly as a reporter for the New York Herald Times, he decided to study law. He graduated with a degree from New York Law School in 1903 and was admitted to the U.S. Bar in 1904. He practised law in New York City until 1916. Though he had serious determination to become a successful lawyer, Stevens had several friends among the New York writers and painters in Greenwich Village, including the poets William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and E. E. Cummings. In 1914, under the pseudonym "Peter Parasol," he sent a group of poems under the title "Phases" to Harriet Monroe for a war poem competition for Poetry magazine. Stevens did not win the prize, but was published by Monroe in November of that year. Stevens moved to Connecticut in 1916, having found employment at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Co., of which he became vice president in 1934. He had began to establish an identity for himself outside the world of law and business, however, and his first book of poems, Harmonium, published in 1923, exhibited the influence of both the English Romantics and the French symbolists, an inclination to aesthetic philosophy, and a wholly original style and sensibility: exotic, whimsical, infused with the light and color of an Impressionist painting. For the next several years, Stevens focused on his business life. He began to publish new poems in 1930, however, and in the following year, Knopf published an second edition of Harmonium, which included fourteen new poems and left out three of the decidedly weaker ones. More than any other modern poet, Stevens was concerned with the transformative power of the imagination. Composing poems on his way to and from the office and in the evenings, Stevens continued to spend his days behind a desk at the office, and led a quiet, uneventful life. Though now considered one of the major American poets of the century, he did not receive widespread recognition until the publication of his Collected Poems, just a year before his death. His major works include Ideas of Order (1935), The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937), Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942), and a collection of essays on poetry, The Necessary Angel (1951). Stevens died in Hartford in 1955. Poetry Harmonium (1923) Ideas of Order (1935) Owl's Clover (1936) The Man With the Blue Guitar (1937) Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction (1942) Parts of a World (1942) Esthétique du Mal (1945) Three Academic Pieces (1947) Transport to Summer (1947) Primitive Like an Orb (1948) Auroras of Autumn (1950) Collected Poems (1954) Opus Posthumous (1957) The Palm at the End of the Mind (1967) Prose The Necessary Angel (1951) Plays Three Travellers Watch the Sunrise (1916) Carlos Among the Candles (1917) References Poets.org — http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/124

#Americans Modern

I am a starving Artist.....waiting for my big Break!!! I am a person of wisdom, who has been through different obstacles in my life to become who I am. I am hard working and honest. I have only a few close people in my life to keep me sane. Through my continuous journey, I have learned that I can control only my own destiny.In time I would love to motive others to live life to their fullest potential. For if we all commit to ourselves, we can help make the world a better place. I have come a long way from the clumsy, awkward, misunderstood, young child, and teen. I have grown into who I want to be. And will make every effort to forgive myself, and others. By doing this I will be able to complete self. And that's my mission in life.

Thomas Henry Kendall (18 April 1839– 1 August 1882) was a nineteenth-century Australian author and bush poet, who was particularly known for his poems and tales set in a natural environment setting. Kendall was born in a settler’s hut by Yackungarrah Creek in Yatte Yattah near Ulladulla, New South Wales. He was registered as Thomas Henry Kendall, but never appears to have used his first name. His three volumes of verse were all published under the name of “Henry Kendall”. His father, Basil Kendall, was the son of the Rev. Thomas Kendall who came to Sydney in 1809 and five years later went as a missionary to New Zealand.

William Ernest Henley (23 August 1849 – 11 July 1903) was an English poet, critic and editor, best remembered for his 1875 poem “Invictus”. Henley was born in Gloucester and was the oldest of a family of six children, five sons and a daughter. His father, William, a bookseller and stationer, died in 1868 and was survived by young children and creditors. His mother, Mary Morgan, was descended from the poet and critic Joseph Wharton. Between 1861 and 1867, Henley was a pupil at the Crypt Grammar School (founded 1539).

William Lisle Bowles (24 September 1762– 7 April 1850) was an English priest, poet and critic. Life and career Bowles was born at King’s Sutton, Northamptonshire, where his father was vicar. At the age of 14 he entered Winchester College, where the headmaster at the time was Dr Joseph Warton. In 1781 Bowles left as captain of the school, and went on to Trinity College, Oxford, where he had won a scholarship. Two years later he won the Chancellor’s prize for Latin verse. Bowles came from a line of Church of England clergymen. His great-grandfather Matthew Bowles (1652–1742), grandfather Dr Thomas Bowles (1696–1773) and father William Thomas Bowles (1728–86) had all been parish priests. After taking his degree at Oxford, Bowles followed his forebears into the Church of England, and in 1792, after serving as curate in Donhead St Andrew, was appointed vicar of Chicklade in Wiltshire. In 1797 he received the vicarage of Dumbleton in Gloucestershire, and in 1804 became vicar of Bremhill in Wiltshire, where he wrote the poem seen on Maud Heath’s statue. In the same year his bishop, John Douglas, collated him to a prebendal stall in Salisbury Cathedral. In 1818 he was made chaplain to the Prince Regent, and in 1828 he was elected residentiary canon of Salisbury. Works * In 1789 he published, in a very small quarto volume, Fourteen Sonnets, which were received with extraordinary favour, not only by the general public, but by such men as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Wordsworth. * The Sonnets even in form were a revival, a return to an older and purer poetic style, and by their grace of expression, melodious versification, tender tone of feeling and vivid appreciation of the life and beauty of nature, stood out in strong contrast to the elaborated commonplaces which at that time formed the bulk of English poetry. Bowles said thereof Poetic trifles from solitary rambles whilst chewing the cud of sweet and bitter fancy, written from memory, confined to fourteen lines, this seemed best adapted to the unity of sentiment, the verse flowed in unpremeditated harmony as my ear directed but are far from being mere elegiac couplets. * The longer poems published by Bowles are not of a very high standard, though all are distinguished by purity of imagination, cultured and graceful diction, and great tenderness of feeling. The most extensive were The Spirit of Discovery (1804), which was mercilessly ridiculed by Lord Byron; The Missionary (1813); The Grave of the Last Saxon (1822); and St John in Patmos (1833). Bowles is perhaps more celebrated as a critic than as a poet.In 1806 he published an edition of Alexander Pope’s works with notes and an essay, in which he laid down certain canons as to poetic imagery which, subject to some modification, were later accepted, but which were received at the time with strong opposition by admirers of Pope and his style. The controversy brought into sharp contrast the opposing views of poetry, which may be roughly described as the natural and the artificial. * Bowles was an amiable, absent-minded, and rather eccentric man. His poems are characterised by refinement of feeling, tenderness, and pensive thought, but are deficient in power and passion. Bowles maintained that images drawn from nature are poetically finer than those drawn from art; and that in the highest kinds of poetry the themes or passions handled should be of the general or elemental kind, and not the transient manners of any society. These positions were attacked by Byron, Thomas Campbell, William Roscoe and others, while for a time Bowles was almost solitary. William Hazlitt and the Blackwood critics came to his assistance, and on the whole Bowles had reason to congratulate himself on having established certain principles which might serve as the basis of a true method of poetical criticism, and of having inaugurated, both by precept and by example, a new era in English poetry. Among other prose works from his prolific pen was a Life of Bishop Ken (two volumes, 1830–1831). Other works include Coombe Ellen and St. Michael’s Mount (1798), The Battle of the Nile (1799), and The Sorrows of Switzerland (1801). * Bowles also enjoyed considerable reputation as an antiquary, his principal work in that department being Hermes Britannicus (1828). His Poetical Works were collected in 1855 as part of the Library Edition of the British Poets, with a memoir by George Gilfillan. Reception * Bowles’ work was important to the young Samuel Taylor Coleridge: * Bowles was the cause in the 1820s of the Alexander Pope controversy into which George Gordon, Lord Byron was drawn. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Lisle_Bowles

Born and raised in Soweto. God, my family and sports and music are the most important things in my life. I started writing poems as a hobby and then developed a greater liking for it. The poems I write are based on the emotions I feel at that time, but also sometimes they are inspired by music & movies. I write poetry to entertain and inspire other people to better themselves and that through them, they will learn & most importantly, know how strong and mighty God is.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and critical thinking, as well as a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society and conformity. Friedrich Nietzsche thought he was “the most gifted of the Americans,” and Walt Whitman called him his “master”.

I work hard and play hard. I am a dad and that is the most important attribute about my self. I have a strong belief in God and trust that he guides me. I also have a soft heart and writing helps getting out the pain i may feel or i may just simply be sharing things i have written in the past. I love to write I do not claim to be good at it, but i enjoy it so much. Writing is my reading. I do not like to read books so writing is my way of exercising my brain. Feel free to critique my writing if it helps me then i thank you, if it is just to banter me then keep it to your self.

Khalil Gibran (January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931); born Gubran Khalil Gubran, was a Lebanese-American artist, poet, and writer. Born in the town of Bsharri in modern-day Lebanon (then part of the Ottoman Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate), as a young man he emigrated with his family to the United States where he studied art and began his literary career. In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a literary and political rebel. His Romantic style was at the heart of a renaissance in modern Arabic literature, especially prose poetry, breaking away from the classical school. In Lebanon, he is still celebrated as a literary hero. He is chiefly known in the English-speaking world for his 1923 book The Prophet, an early example of inspirational fiction including a series of philosophical essays written in poetic English prose. The book sold well despite a cool critical reception, gaining popularity in the 1930s and again especially in the 1960s counterculture. Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu.

Frances Anne “Fanny” Kemble (27 November 1809– 15 January 1893) was a notable British actress from a theatre family in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and popular writer, whose published works included plays, poetry, eleven volumes of memoirs, travel writing and works about the theatre.

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer who wrote exclusively in English. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories and scripts for film and radio, which he often performed himself. His public readings, particularly in America, won him great acclaim; his sonorous voice with a subtle Welsh lilt became almost as famous as his works. His best-known works include the “play for voices” Under Milk Wood and the celebrated villanelle for his dying father, “Do not go gentle into that good night”. Appreciative critics have also noted the craftsmanship and compression of poems such as “In my Craft or Sullen Art”, and the rhapsodic lyricism in “And death shall have no dominion” and “Fern Hill”.

I have been writing poetry since 2011 and I love doing it because I can express myself. I was bored one day and pick up a pen and paper and started putting words together on paper and now I am passionate about it. I write songs and short stories also but I am more better at writing poetry. I love music very much and I love fashion.

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that “the negro was in vogue” which was later paraphrased as “when Harlem was in vogue”.

Born in Srilanka, I migrated to Canada in 1999. I was a teacher and Lecturer in Srilanka, where I taught both in secondary schools, teachers' colleges and some part-time work at the university of Jaffna. I have also about eight years of teaching experience in Nigeria. I also taught in Canada-both as a supply teacher and an ESL teacher for newcomers to Canada. My teaching subjects were Geography, English, Western History and Principles of Education. I had interest in writing poetry right from my school days, though I am not an expert at it. I am always trying to improve and joining the poet's sanctuary is an outcome of that intention.

John Boyle O’Reilly (28 June 1844–10 August 1890) was an Irish-born poet, journalist and fiction writer. As a youth in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, for which he was transported to Western Australia. After escaping to the United States, he became a prominent spokesperson for the Irish community and culture, through his editorship of the Boston newspaper The Pilot, his prolific writing, and his lecture tours.

Hey everyone!!!:) My name is crystal R. Things about me...:) . Varsity cheerleader at my high school . Short .Loud .shy .competitive .nice . sometimes funny .Favorite subject is math .Favorite colors are baby blue and pink Sports I played/play....:) . Basketball .Track .Volley ball .cheerleading My writing....:) . I only write poems . About love, life, friends, struggles, just basically anything . Started writing in 4th grade then I stopped then started writing again in 7th grade .I write because it's a good way to express myself. Oh, and to anyone who follows me, read my stuff, or comment on anything of mine, I wanna say thank you:) And please if you read my stuff to please comment:) And I know I'm not the best writer but please comment:) Thanks:) And if you have any questions about me or anything feel free to message me:)

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

#Americans #Lesbian #PulitzerPrize #Women

.jpeg)