Info

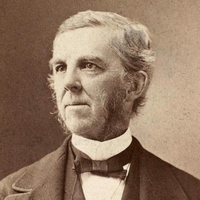

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the Fireside Poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet Robert Burns. Whittier is remembered particularly for his anti-slavery writings as well as his book Snow-Bound. Early life and work John Greenleaf Whittier was born to John and Abigail (Hussey) at their rural homestead in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on December 17, 1807. His middle name is thought to mean 'feuillevert' after his Huguenot forbears. He grew up on the farm in a household with his parents, a brother and two sisters, a maternal aunt and paternal uncle, and a constant flow of visitors and hired hands for the farm. As a boy, it was discovered that Whittier was color-blind when he was unable to see a difference between ripe and unripe strawberries. Their farm was not very profitable and there was only enough money to get by. Whittier himself was not cut out for hard farm labor and suffered from bad health and physical frailty his whole life. Although he received little formal education, he was an avid reader who studied his father's six books on Quakerism until their teachings became the foundation of his ideology. Whittier was heavily influenced by the doctrines of his religion, particularly its stress on humanitarianism, compassion, and social responsibility. Whittier was first introduced to poetry by a teacher. His sister sent his first poem, "The Exile's Departure", to the Newburyport Free Press without his permission and its editor, William Lloyd Garrison, published it on June 8, 1826. Garrison as well as another local editor encouraged Whittier to attend the recently opened Haverhill Academy. To raise money to attend the school, Whittier became a shoemaker for a time, and a deal was made to pay part of his tuition with food from the family farm. Before his second term, he earned money to cover tuition by serving as a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in what is now Merrimac, Massachusetts. He attended Haverhill Academy from 1827 to 1828 and completed a high school education in only two terms. Garrison gave Whittier the job of editor of the National Philanthropist, a Boston-based temperance weekly. Shortly after a change in management, Garrison reassigned him as editor of the weekly American Manufacturer in Boston. Whittier became an out-spoken critic of President Andrew Jackson, and by 1830 was editor of the prominent New England Weekly Review in Hartford, Connecticut, the most influential Whig journal in New England. In 1833 he published The Song of the Vermonters, 1779, which he had anonymously inserted in The New England Magazine. The poem was erroneously attributed to Ethan Allen for nearly sixty years. Abolitionist activity During the 1830s, Whittier became interested in politics but, after losing a Congressional election at age twenty-five, he suffered a nervous breakdown and returned home. The year 1833 was a turning point for Whittier; he resurrected his correspondence with Garrison, and the passionate abolitionist began to encourage the young Quaker to join his cause. In 1833, Whittier published the antislavery pamphlet Justice and Expediency, and from there dedicated the next twenty years of his life to the abolitionist cause. The controversial pamphlet destroyed all of his political hopes — as his demand for immediate emancipation alienated both northern businessmen and southern slaveholders — but it also sealed his commitment to a cause that he deemed morally correct and socially necessary. He was a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society and signed the Anti-Slavery Declaration of 1833, which he often considered the most significant action of his life. Whittier's political skill made him useful as a lobbyist, and his willingness to badger anti-slavery congressional leaders into joining the abolitionist cause was invaluable. From 1835 to 1838, he traveled widely in the North, attending conventions, securing votes, speaking to the public, and lobbying politicians. As he did so, Whittier received his fair share of violent responses, being several times mobbed, stoned, and run out of town. From 1838 to 1840, he was editor of The Pennsylvania Freeman in Philadelphia, one of the leading antislavery papers in the North, formerly known as the National Enquirer. In May 1838, the publication moved its offices to the newly opened Pennsylvania Hall on North Sixth Street, which was shortly after burned by a pro-slavery mob. Whittier also continued to write poetry and nearly all of his poems in this period dealt with the problem of slavery. By the end of the 1830s, the unity of the abolitionist movement had begun to fracture. Whittier stuck to his belief that moral action apart from political effort was futile. He knew that success required legislative change, not merely moral suasion. This opinion alone engendered a bitter split from Garrison,[citation needed] and Whittier went on to become a founding member of the Liberty Party in 1839. In 1840 he attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. By 1843, he was announcing the triumph of the fledgling party: "Liberty party is no longer an experiment. It is vigorous reality, exerting... a powerful influence". Whittier also unsuccessfully encouraged Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to join the party. He took editing jobs with the Middlesex Standard in Lowell, Massachusetts and the Essex Transcript in Amesbury until 1844. While in Lowell, he met Lucy Larcom, who became a lifelong friend. In 1845, he began writing his essay "The Black Man" which included an anecdote about John Fountain, a free black who was jailed in Virginia for helping slaves escape. After his release, Fountain went on a speaking tour and thanked Whittier for writing his story. Around this time, the stresses of editorial duties, worsening health, and dangerous mob violence caused him to have a physical breakdown. Whittier went home to Amesbury, and remained there for the rest of his life, ending his active participation in abolition. Even so, he continued to believe that the best way to gain abolitionist support was to broaden the Liberty Party's political appeal, and Whittier persisted in advocating the addition of other issues to their platform. He eventually participated in the evolution of the Liberty Party into the Free Soil Party, and some say his greatest political feat was convincing Charles Sumner to run on the Free-Soil ticket for the U.S. Senate in 1850. Beginning in 1847, Whittier was editor of Gamaliel Bailey's The National Era, one of the most influential abolitionist newspapers in the North. For the next ten years it featured the best of his writing, both as prose and poetry. Being confined to his home and away from the action offered Whittier a chance to write better abolitionist poetry; he was even poet laureate for his party. Whittier's poems often used slavery to represent all kinds of oppression (physical, spiritual, economic), and his poems stirred up popular response because they appealed to feelings rather than logic. Whittier produced two collections of antislavery poetry: Poems Written during the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States, between 1830 and 1838 and Voices of Freedom (1846). He was an elector in the presidential election of 1860 and of 1864, voting for Abraham Lincoln both times. The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 ended both slavery and his public cause, so Whittier turned to other forms of poetry for the remainder of his life. Criticism Nathaniel Hawthorne dismissed Whittier's Literary Recreations and Miscellanies (1854): "Whittier's book is poor stuff! I like the man, but have no high opinion either of his poetry or his prose." Editor George Ripley, however, found Whittier's poetry refreshing and said it had a "stately movement of versification, grandeur of imagery, a vein of tender and solemn pathos, cheerful trust" and a "pure and ennobling character". Boston critic Edwin Percy Whipple noted Whittier's moral and ethical tone mingled with sincere emotion. He wrote, "In reading this last volume, I feel as if my soul had taken a bath in holy water." Later scholars and critics questioned the depth of Whittier's poetry. One was Karl Keller, who noted, "Whittier has been a writer to love, not to belabor." Influence and legacy Whittier was particularly supportive of women writers, including Alice Cary, Phoebe Cary, Sarah Orne Jewett, Lucy Larcom, and Celia Thaxter. He was especially influential in prose writings by Jewett, with whom he shared a belief in the moral quality of literature and an interest New England folklore. Jewett dedicated one of her books to him and modeled several of her characters after people in Whittier's life. Whittier's family farm, known as the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead or simply "Whittier's Birthplace", is now a historic site open to the public. His later residence in Amesbury, where he lived for 56 years, is also open to the public, and is now known as the John Greenleaf Whittier Home. Whittier's hometown of Haverhill has named many buildings and landmarks in his honor including J.G. Whittier Middle School, Greenleaf Elementary, and Whittier Regional Vocational Technical High School. Numerous other schools around the country also bear his name. A bridge named for Whittier, built in the style of the Sagamore and Bourne Bridges, carries Interstate 95 from Amesbury to Newburyport over the Merrimack River. A covered bridge spanning the Bearcamp River in Ossipee, New Hampshire is also named for Whittier, as is a nearby mountain. The city of Whittier, California is named after the poet, as are the communities of Whittier, Alaska, and Whittier, Iowa, the Minneapolis neighborhood of Whittier, the Denver, Colorado, neighborhood of Whittier, and the town of Greenleaf, Idaho. Both Whittier College and Whittier Law School are also named after him. A park in the Saint Boniface area of Winnipeg is named after the poet in recognition of his poem "The Red River Voyageur". Whittier Education Campus in Washington, DC is named in his honor. The alternate history story P.'s Correspondence (1846) by Nathaniel Hawthorne, considered the first such story ever published in English, includes the notice "Whittier, a fiery Quaker youth, to whom the muse had perversely assigned a battle-trumpet, got himself lynched, in South Carolina". The date of that event in Hawthorne's invented timeline was 1835. Whittier was one of thirteen writers in the 1897 card game Authors and referenced his writings "Laus Deo", "Among the Hills", Snow-bound, and "The Eternal Goodness". He was removed from the card game when it was reissued in 1987. LIST OF WORKS Poetry collections Poems written during the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States (1837) Lays of My Home (1843) Voices of Freedom (1846) Songs of Labor (1850) The Chapel of the Hermits (1853) Le Marais du Cygne (September 1858 Atlantic Monthly) Home Ballads (1860) The Furnace Blast (1862) Maud Muller (1856) In War Time (1864) Snow-Bound (1866) The Tent on the Beach (1867) Among the Hills (1869) Whittier's Poems Complete (1874)[citation needed] *The Pennsylvania Pilgrim (1872) The Vision of Echard (1878) The King's Missive (1881) Saint Gregory's Guest (1886) At Sundown (1890) Prose The Stranger in Lowell (1845) The Supernaturalism of New England (1847) Leaves from Margaret Smith's Journal (1849) Old Portraits and Modern Sketches (1850) Literary Recreations and Miscellanies (1854) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Greenleaf_Whittier

I have been a hopeless romantic since I was a young boy. I have always been drawn to relationships and the experience of love. The exhilaration and emotions that flood into and coarse through those that are in love is the most intoxicating feeling possible, at least in my opinion. As you read these poems, you are reading my story. I write about my thoughts, my feelings, and my experiences. Forgive me if my writings are not of your flavor as I never did read much poetry from others.

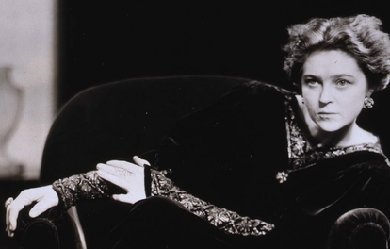

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death. Barrett Browning opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of slavers and her support for the abolitionist cause. The poems opposing slavery include "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation"; in the first she describes the experience of a slave woman who is whipped, raped, and made pregnant as she curses the slavers. She declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Emancipation Act abolishing slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833, despite the fact that her father believed that Abolitionism would ruin his business.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (21 October 1772 – 25 July 1834) was an English poet, Romantic, literary critic and philosopher who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets. He is probably best known for his poems The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan, as well as for his major prose work Biographia Literaria. His critical work, especially on Shakespeare, was highly influential, and he helped introduce German idealist philosophy to English-speaking culture. He coined many familiar words and phrases, including the celebrated suspension of disbelief. He was a major influence, via Emerson, on American transcendentalism. Throughout his adult life, Coleridge suffered from crippling bouts of anxiety and depression; it has been speculated by some that he suffered from bipolar disorder, a condition as yet unidentified during his lifetime. Coleridge suffered from poor health that may have stemmed from a bout of rheumatic fever and other childhood illnesses. He was treated for these concerns with laudanum, which fostered a lifelong opium addiction. Early life Coleridge was born on 21 October 1772 in the country town of Ottery St Mary, Devon, England. Samuel's father, the Reverend John Coleridge (1718–1781), was a well-respected vicar of the parish and headmaster of Henry VIII's Free Grammar School at Ottery. He had three children by his first wife. Samuel was the youngest of ten by Reverend Coleridge's second wife, Anne Bowden (1726–1809). Coleridge suggests that he "took no pleasure in boyish sports" but instead read "incessantly" and played by himself. After John Coleridge died in 1781, 8-year-old Samuel was sent to Christ's Hospital, a charity school founded in the 16th century in Greyfriars, London, where he remained throughout his childhood, studying and writing poetry. At that school Coleridge became friends with Charles Lamb, a schoolmate, and studied the works of Virgil and William Lisle Bowles. In one of a series of autobiographical letters written to Thomas Poole, Coleridge wrote: "At six years old I remember to have read Belisarius, Robinson Crusoe, and Philip Quarll – and then I found the Arabian Nights' Entertainments – one tale of which (the tale of a man who was compelled to seek for a pure virgin) made so deep an impression on me (I had read it in the evening while my mother was mending stockings) that I was haunted by spectres whenever I was in the dark – and I distinctly remember the anxious and fearful eagerness with which I used to watch the window in which the books lay – and whenever the sun lay upon them, I would seize it, carry it by the wall, and bask, and read.” However, Coleridge seems to have appreciated his teacher, as he wrote in recollections of his schooldays in Biographia Literaria: I enjoyed the inestimable advantage of a very sensible, though at the same time, a very severe master [...] At the same time that we were studying the Greek Tragic Poets, he made us read Shakespeare and Milton as lessons: and they were the lessons too, which required most time and trouble to bring up, so as to escape his censure. I learnt from him, that Poetry, even that of the loftiest, and, seemingly, that of the wildest odes, had a logic of its own, as severe as that of science; and more difficult, because more subtle, more complex, and dependent on more, and more fugitive causes. [...] In our own English compositions (at least for the last three years of our school education) he showed no mercy to phrase, metaphor, or image, unsupported by a sound sense, or where the same sense might have been conveyed with equal force and dignity in plainer words... In fancy I can almost hear him now, exclaiming Harp? Harp? Lyre? Pen and ink, boy, you mean! Muse, boy, Muse? your Nurse's daughter, you mean! Pierian spring? Oh aye! the cloister-pump, I suppose! [...] Be this as it may, there was one custom of our master's, which I cannot pass over in silence, because I think it ... worthy of imitation. He would often permit our theme exercises, ... to accumulate, till each lad had four or five to be looked over. Then placing the whole number abreast on his desk, he would ask the writer, why this or that sentence might not have found as appropriate a place under this or that other thesis: and if no satisfying answer could be returned, and two faults of the same kind were found in one exercise, the irrevocable verdict followed, the exercise was torn up, and another on the same subject to be produced, in addition to the tasks of the day. Throughout his life, Coleridge idealized his father as pious and innocent, while his relationship with his mother was more problematic. His childhood was characterized by attention seeking, which has been linked to his dependent personality as an adult. He was rarely allowed to return home during the school term, and this distance from his family at such a turbulent time proved emotionally damaging. He later wrote of his loneliness at school in the poem Frost at Midnight: "With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt/Of my sweet birthplace." From 1791 until 1794, Coleridge attended Jesus College, Cambridge. In 1792, he won the Browne Gold Medal for an ode that he wrote on the slave trade. In December 1793, he left the college and enlisted in the Royal Dragoons using the false name "Silas Tomkyn Comberbache", perhaps because of debt or because the girl that he loved, Mary Evans, had rejected him. Afterwards, he was rumoured to have had a bout of severe depression. His brothers arranged for his discharge a few months later under the reason of "insanity" and he was readmitted to Jesus College, though he would never receive a degree from Cambridge. Pantisocracy and marriage At the university, he was introduced to political and theological ideas then considered radical, including those of the poet Robert Southey. Coleridge joined Southey in a plan, soon abandoned, to found a utopian commune-like society, called Pantisocracy, in the wilderness of Pennsylvania. In 1795, the two friends married sisters Sarah and Edith Fricker, in St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, but Coleridge's marriage proved unhappy. He grew to detest his wife, whom he only married because of social constraints. He eventually separated from her. Coleridge made plans to establish a journal, The Watchman, to be printed every eight days in order to avoid a weekly newspaper tax. The first issue of the short-lived journal was published in March 1796; it had ceased publication by May of that year. The years 1797 and 1798, during which he lived in what is now known as Coleridge Cottage, in Nether Stowey, Somerset, were among the most fruitful of Coleridge's life. In 1795, Coleridge met poet William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy. (Wordsworth, having visited him and being enchanted by the surroundings, rented Alfoxton Park, a little over three miles [5 km] away.) Besides the Rime of The Ancient Mariner, he composed the symbolic poem Kubla Khan, written—Coleridge himself claimed—as a result of an opium dream, in "a kind of a reverie"; and the first part of the narrative poem Christabel. The writing of Kubla Khan, written about the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan and his legendary palace at Xanadu, was said to have been interrupted by the arrival of a "Person from Porlock" — an event that has been embellished upon in such varied contexts as science fiction and Nabokov's Lolita. During this period, he also produced his much-praised "conversation" poems This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison, Frost at Midnight, and The Nightingale. In 1798, Coleridge and Wordsworth published a joint volume of poetry, Lyrical Ballads, which proved to be the starting point for the English romantic movement. Wordsworth may have contributed more poems, but the real star of the collection was Coleridge's first version of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. It was the longest work and drew more praise and attention than anything else in the volume. In the spring Coleridge temporarily took over for Rev. Joshua Toulmin at Taunton's Mary Street Unitarian Chapel while Rev. Toulmin grieved over the drowning death of his daughter Jane. Poetically commenting on Toulmin's strength, Coleridge wrote in a 1798 letter to John Prior Estlin, "I walked into Taunton (eleven miles) and back again, and performed the divine services for Dr. Toulmin. I suppose you must have heard that his daughter, (Jane, on 15 April 1798) in a melancholy derangement, suffered herself to be swallowed up by the tide on the sea-coast between Sidmouth and Bere [sic] (Beer). These events cut cruelly into the hearts of old men: but the good Dr. Toulmin bears it like the true practical Christian, – there is indeed a tear in his eye, but that eye is lifted up to the Heavenly Father." In the autumn of 1798, Coleridge and Wordsworth left for a stay in Germany; Coleridge soon went his own way and spent much of his time in university towns. During this period, he became interested in German philosophy, especially the transcendental idealism and critical philosophy of Immanuel Kant, and in the literary criticism of the 18th century dramatist Gotthold Lessing. Coleridge studied German and, after his return to England, translated the dramatic trilogy Wallenstein by the German Classical poet Friedrich Schiller into English. He continued to pioneer these ideas through his own critical writings for the rest of his life (sometimes without attribution), although they were unfamiliar and difficult for a culture dominated by empiricism. In 1799, Coleridge and Wordsworth stayed at Thomas Hutchinson's farm on the Tees at Sockburn, near Darlington. It was at Sockburn that Coleridge wrote his ballad-poem Love, addressed to Sara. The knight mentioned is the mailed figure on the Conyers tomb in ruined Sockburn church. The figure has a wyvern at his feet, a reference to the Sockburn worm slain by Sir John Conyers (and a possible source for Lewis Carroll's Jabberwocky). The worm was supposedly buried under the rock in the nearby pasture; this was the 'greystone' of Coleridge's first draft, later transformed into a 'mount'. The poem was a direct inspiration for John Keats' famous poem La Belle Dame Sans Merci. Coleridge's early intellectual debts, besides German idealists like Kant and critics like Lessing, were first to William Godwin's Political Justice, especially during his Pantisocratic period, and to David Hartley's Observations on Man, which is the source of the psychology which is found in Frost at Midnight. Hartley argued that one becomes aware of sensory events as impressions, and that "ideas" are derived by noticing similarities and differences between impressions and then by naming them. Connections resulting from the coincidence of impressions create linkages, so that the occurrence of one impression triggers those links and calls up the memory of those ideas with which it is associated (See Dorothy Emmet, "Coleridge and Philosophy"). Coleridge was critical of the literary taste of his contemporaries, and a literary conservative insofar as he was afraid that the lack of taste in the ever growing masses of literate people would mean a continued desecration of literature itself. In 1800, he returned to England and shortly thereafter settled with his family and friends at Keswick in the Lake District of Cumberland to be near Grasmere, where Wordsworth had moved. Soon, however, he was beset by marital problems, illnesses, increased opium dependency, tensions with Wordsworth, and a lack of confidence in his poetic powers, all of which fuelled the composition of Dejection: An Ode and an intensification of his philosophical studies. Later life and increasing drug use In 1804, he travelled to Sicily and Malta, working for a time as Acting Public Secretary of Malta under the Commissioner, Alexander Ball, a task he performed quite successfully. However, he gave this up and returned to England in 1806. Dorothy Wordsworth was shocked at his condition upon his return. From 1807 to 1808, Coleridge returned to Malta and then travelled in Sicily and Italy, in the hope that leaving Britain's damp climate would improve his health and thus enable him to reduce his consumption of opium. Thomas de Quincey alleges in his Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets that it was during this period that Coleridge became a full-blown opium addict, using the drug as a substitute for the lost vigour and creativity of his youth. It has been suggested, however, that this reflects de Quincey's own experiences more than Coleridge's. His opium addiction (he was using as much as two quarts of laudanum a week) now began to take over his life: he separated from his wife Sarah in 1808, quarrelled with Wordsworth in 1810, lost part of his annuity in 1811, and put himself under the care of Dr. Daniel in 1814. In 1809, Coleridge made his second attempt to become a newspaper publisher with the publication of the journal entitled The Friend. It was a weekly publication that, in Coleridge’s typically ambitious style, was written, edited, and published almost entirely single-handedly. Given that Coleridge tended to be highly disorganized and had no head for business, the publication was probably doomed from the start. Coleridge financed the journal by selling over five hundred subscriptions, over two dozen of which were sold to members of Parliament, but in late 1809, publication was crippled by a financial crisis and Coleridge was obliged to approach "Conversation Sharp", Tom Poole and one or two other wealthy friends for an emergency loan in order to continue. The Friend was an eclectic publication that drew upon every corner of Coleridge’s remarkably diverse knowledge of law, philosophy, morals, politics, history, and literary criticism. Although it was often turgid, rambling, and inaccessible to most readers, it ran for 25 issues and was republished in book form a number of times. Years after its initial publication, The Friend became a highly influential work and its effect was felt on writers and philosophers from J.S. Mill to Emerson. Between 1810 and 1820, this "giant among dwarfs", as he was often considered by his contemporaries, gave a series of lectures in London and Bristol – those on Shakespeare renewed interest in the playwright as a model for contemporary writers. Much of Coleridge's reputation as a literary critic is founded on the lectures that he undertook in the winter of 1810–11 which were sponsored by the Philosophical Institution and given at Scot's Corporation Hall off Fetter Lane, Fleet Street. These lectures were heralded in the prospectus as "A Course of Lectures on Shakespeare and Milton, in Illustration of the Principles of Poetry." Coleridge's ill-health, opium-addiction problems, and somewhat unstable personality meant that all his lectures were plagued with problems of delays and a general irregularity of quality from one lecture to the next. Furthermore, Coleridge's mind was extremely dynamic and his personality was spasmodic. As a result of these factors, Coleridge often failed to prepare anything but the loosest set of notes for his lectures and regularly entered into extremely long digressions which his audiences found difficult to follow. However, it was the lecture on Hamlet given on 2 January 1812 that was considered the best and has influenced Hamlet studies ever since. Before Coleridge, Hamlet was often denigrated and belittled by critics from Voltaire to Dr. Johnson. Coleridge rescued Hamlet and his thoughts on the play are often still published as supplements to the text. In August 1814, Coleridge was approached by Lord Byron's publisher, John Murray, about the possibility of translating Goethe's classic Faust (1808). Coleridge was regarded by many as the greatest living writer on the demonic and he accepted the commission, only to abandon work on it after six weeks. Until recently, scholars have accepted that Coleridge never returned to the project, despite Goethe's own belief in the 1820s that Coleridge had in fact completed a long translation of the work. In September 2007, Oxford University Press sparked a heated scholarly controversy by publishing an English translation of Goethe's work which purported to be Coleridge's long-lost masterpiece (the text in question first appeared anonymously in 1821). In 1817, Coleridge, with his addiction worsening, his spirits depressed, and his family alienated, took residence in the Highgate homes, then just north of London, of the physician James Gillman, first at South Grove and later at the nearby 3 The Grove. Gillman was partially successful in controlling the poet's addiction. Colerdige remained in Highgate for the rest of his life, and the house became a place of literary pilgrimage of writers including Carlyle and Emerson. In Gillman's home, he finished his major prose work, the Biographia Literaria (1817), a volume composed of 23 chapters of autobiographical notes and dissertations on various subjects, including some incisive literary theory and criticism. He composed much poetry here and had many inspirations — a few of them from opium overdose. Perhaps because he conceived such grand projects, he had difficulty carrying them through to completion, and he berated himself for his "indolence". It is unclear whether his growing use of opium (and the brandy in which it was dissolved) was a symptom or a cause of his growing depression. He published other writings while he was living at the Gillman home, notably Sibylline Leaves (1817), Aids to Reflection (1825), and Church and State (1826). He died in Highgate, London on 25 July 1834 as a result of heart failure compounded by an unknown lung disorder, possibly linked to his use of opium. Coleridge had spent 18 years under the roof of the Gillman family, who built an addition onto their home to accommodate the poet. Carlyle described him at Highgate: "Coleridge sat on the brow of Highgate Hill, in those years, looking down on London and its smoke-tumult, like a sage escaped from the inanity of life`s battle ... The practical intellects of the world did not much heed him, or carelessly reckoned him a metaphysical dreamer: but to the rising spirits of the young generation he had this dusky sublime character; and sat there as a kind of Magus, girt in mystery and enigma; his Dodona oak-grove (Mr. Gilman`s house at Highgate) whispering strange things, uncertain whether oracles or jargon." Poetry Despite not enjoying the name recognition or popular acclaim that Wordsworth or Shelley have had, Coleridge is one of the most important figures in English poetry. His poems directly and deeply influenced all the major poets of the age. He was known by his contemporaries as a meticulous craftsman who was more rigorous in his careful reworking of his poems than any other poet, and Southey and Wordsworth were dependent on his professional advice. His influence on Wordsworth is particularly important because many critics have credited Coleridge with the very idea of "Conversational Poetry". The idea of utilizing common, everyday language to express profound poetic images and ideas for which Wordsworth became so famous may have originated almost entirely in Coleridge’s mind. It is difficult to imagine Wordsworth’s great poems, The Excursion or The Prelude, ever having been written without the direct influence of Coleridge’s originality. As important as Coleridge was to poetry as a poet, he was equally important to poetry as a critic. Coleridge's philosophy of poetry, which he developed over many years, has been deeply influential in the field of literary criticism. This influence can be seen in such critics as A.O. Lovejoy and I.A. Richards. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Christabel, and Kubla Khan Coleridge is probably best known for his long poems, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Christabel. Even those who have never read the Rime have come under its influence: its words have given the English language the metaphor of an albatross around one's neck, the quotation of "water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink" (almost always rendered as "but not a drop to drink"), and the phrase "a sadder and a wiser man" (again, usually rendered as "sadder but wiser man"). The phrase "All creatures great and small" may have been inspired by The Rime: "He prayeth best, who loveth best;/ All things great and small;/ For the dear God who loveth us;/ He made and loveth all."Christabel is known for its musical rhythm, language, and its Gothic tale. Kubla Khan, or, A Vision in a Dream, A Fragment, although shorter, is also widely known. Both Kubla Khan and Christabel have an additional "Romantic" aura because they were never finished. Stopford Brooke characterised both poems as having no rival due to their "exquisite metrical movement" and "imaginative phrasing.” The Conversation poems * The Eolian Harp (1795) * Reflections on having left a Place of Retirement (1795) * This Lime-Tree Bower my Prison (1797) * Frost at Midnight (1798) * Fears in Solitude (1798) * The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem (1798) * Dejection: An Ode (1802) * To William Wordsworth (1807) The eight of Coleridge's poems listed above are now often discussed as a group entitled "Conversation poems". The term itself was coined in 1928 by George McLean Harper, who borrowed the subtitle of The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem (1798) to describe the seven other poems as well. The poems are considered by many critics to be among Coleridge's finest verses; thus Harold Bloom has written, "With Dejection, The Ancient Mariner, and Kubla Khan, Frost at Midnight shows Coleridge at his most impressive." They are also among his most influential poems, as discussed further below. Harper himself considered that the eight poems represented a form of blank verse that is "...more fluent and easy than Milton's, or any that had been written since Milton". In 2006 Robert Koelzer wrote about another aspect of this apparent "easiness", noting that Conversation poems such as "... Coleridge's The Eolian Harp and The Nightingale maintain a middle register of speech, employing an idiomatic language that is capable of being construed as un-symbolic and un-musical: language that lets itself be taken as 'merely talk' rather than rapturous 'song'." The last ten lines of "Frost at Midnight" were chosen by Harper as the "best example of the peculiar kind of blank verse Coleridge had evolved, as natural-seeming as prose, but as exquisitely artistic as the most complicated sonnet." The speaker of the poem is addressing his infant son, asleep by his side: Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee, Whether the summer clothe the general earth With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall Heard only in the trances of the blast, Or if the secret ministry of frost Shall hang them up in silent icicles, Quietly shining to the quiet Moon. In 1965, M. H. Abrams wrote a broad description that applies to the Conversation poems: "The speaker begins with a description of the landscape; an aspect or change of aspect in the landscape evokes a varied by integral process of memory, thought, anticipation, and feeling which remains closely intervolved with the outer scene. In the course of this meditation the lyric speaker achieves an insight, faces up to a tragic loss, comes to a moral decision, or resolves an emotional problem. Often the poem rounds itself to end where it began, at the outer scene, but with an altered mood and deepened understanding which is the result of the intervening meditation." In fact, Abrams was describing both the Conversation poems and later poems influenced by them. Abrams' essay has been called a "touchstone of literary criticism". As Paul Magnuson described it in 2002, "Abrams credited Coleridge with originating what Abrams called the 'greater Romantic lyric', a genre that began with Coleridge's 'Conversation' poems, and included Wordsworth's Tintern Abbey, Shelley's Stanzas Written in Dejection and Keats's Ode to a Nightingale, and was a major influence on more modern lyrics by Matthew Arnold, Walt Whitman, Wallace Stevens, and W. H. Auden.” Literary criticism In addition to his poetry, Coleridge also wrote influential pieces of literary criticism including Biographia Literaria, a collection of his thoughts and opinions on literature which he published in 1817. The work delivered both biographical explanations of the author's life as well as his impressions on literature. The collection also contained an analysis of a broad range of philosophical principles of literature ranging from Aristotle to Immanuel Kant and Schelling and applied them to the poetry of peers such as William Wordsworth. Coleridge's explanation of metaphysical principles were popular topics of discourse in academic communities throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and T.S. Eliot stated that he believed that Coleridge was "perhaps the greatest of English critics, and in a sense the last." Eliot suggests that Coleridge displayed "natural abilities" far greater than his contemporaries, dissecting literature and applying philosophical principles of metaphysics in a way that brought the subject of his criticisms away from the text and into a world of logical analysis that mixed logical analysis and emotion. However, Eliot also criticizes Coleridge for allowing his emotion to play a role in the metaphysical process, believing that critics should not have emotions that are not provoked by the work being studied. Hugh Kenner in Historical Fictions, discusses Norman Furman's Coleridge, the Damaged Archangel and suggests that the term "criticism" is too often applied to Biographia Literaria, which both he and Furman describe as having failed to explain or help the reader understand works of art. To Kenner, Coleridge's attempt to discuss complex philosophical concepts without describing the rational process behind them displays a lack of critical thinking that makes the volume more of a biography than a work of criticism. In Biographia Literaria and his poetry, symbols are not merely "objective correlatives" to Coleridge, but instruments for making the universe and personal experience intelligible and spiritually covalent. To Coleridge, the "cinque spotted spider," making its way upstream "by fits and starts," [Biographia Literaria] is not merely a comment on the intermittent nature of creativity, imagination, or spiritual progress, but the journey and destination of his life. The spider's five legs represent the central problem that Coleridge lived to resolve, the conflict between Aristotelian logic and Christian philosophy. Two legs of the spider represent the "me-not me" of thesis and antithesis, the idea that a thing cannot be itself and its opposite simultaneously, the basis of the clockwork Newtonian world view that Coleridge rejected. The remaining three legs—exothesis, mesothesis and synthesis or the Holy trinity—represent the idea that things can diverge without being contradictory. Taken together, the five legs—with synthesis in the center, form the Holy Cross of Ramist logic. The cinque-spotted spider is Coleridge's emblem of holism, the quest and substance of Coleridge's thought and spiritual life. Coleridge and the influence of the Gothic Coleridge wrote reviews of Ann Radcliffe’s books and The Mad Monk, among others. He comments in his reviews: "Situations of torment, and images of naked horror, are easily conceived; and a writer in whose works they abound, deserves our gratitude almost equally with him who should drag us by way of sport through a military hospital, or force us to sit at the dissecting-table of a natural philosopher. To trace the nice boundaries, beyond which terror and sympathy are deserted by the pleasurable emotions, – to reach those limits, yet never to pass them, hic labor, hic opus est." and "The horrible and the preternatural have usually seized on the popular taste, at the rise and decline of literature. Most powerful stimulants, they can never be required except by the torpor of an unawakened, or the languor of an exhausted, appetite... We trust, however, that satiety will banish what good sense should have prevented; and that, wearied with fiends, incomprehensible characters, with shrieks, murders, and subterraneous dungeons, the public will learn, by the multitude of the manufacturers, with how little expense of thought or imagination this species of composition is manufactured." However, Coleridge used these elements in poems such as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), Christabel and Kubla Khan (published in 1816, but known in manuscript form before then) and certainly influenced other poets and writers of the time. Poems like these both drew inspiration from and helped to inflame the craze for Gothic romance. Mary Shelley, who knew Coleridge well, mentions The Rime of the Ancient Mariner twice directly in Frankenstein, and some of the descriptions in the novel echo it indirectly. Although William Godwin, her father, disagreed with Coleridge on some important issues, he respected his opinions and Coleridge often visited the Godwins. Mary Shelley later recalled hiding behind the sofa and hearing his voice chanting The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Taylor_Coleridge

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in lowercase letters as e.e. cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization, below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

.jpg)

One that knows about the beauty of simplicity. Although giving up to the temptation of complexity, severing the link with the eventual reader. As time allows I'll post brief explanations of knots and obscure references that were not avoided. Not a fan of editing, outside real English native speakers reality. So pardon me for all artificiality. I am trying to make amends to my native language, an ongoing project. As English literature is concerned and especially American, British and Irish poetry... I love it. Beyond any regret, written words may conflict with the spirit of times. I don't aspire, rather transpire toxic thoughts, beauty feeds equilibrium. Ethics and principles, hope and resilience. I see that bucket of Web Dubois. Subtle take over that I never thought possible twenty years ago, on the turn of 20th century, full of lessons turned into caricatures by a cold underlying, unrevealed power(s). And yet, "quality of life" has never been higher, even for "the dispossessed". Looking closely, hearing whispers returning, how would I like to live other people's lives, to ascertain facts and legends. Pace of life, mythologic infinity, eradicated impossible. Maybe. But if here remains even one "pico of doubt"...( maybe not). For those who read strange portuguese...one exemple infra. https://www.escritas.org/pt/n/mgenthbjpafa21 (credits: yukino_neko_girl_anime_star_wreath. Congrats for the art.)

I was born in Hamilton, Ohio, in 1925, a confession that I am an old geezer. I served in the infantry during World War II, was wounded and discharged in 1946. I then obtained a B.A. degree with honors in English in 1949. Subsequently I taught in Cincinnati public schools and at the University of Cincinnati for the next 35 years. My poetry has appeared in: * Wall Street Journal * Hellas * Lyric * Envoi * Midwest Poetry Review (a sonnet won awards) * Aethlon * Light * Poet's View * Classical Outlook * Mind over Matter Several books have been self-published but Wormwood and Whines, a compilation of many of my poems, was published by Superior Books in 1999.

Edward James (Ted) Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding district of Yorkshire, on August 17, 1930. His childhood was quiet and dominately rural. When he was seven years old, his family moved to the small town of Mexborough in South Yorkshire, and the landscape of the moors of that area informed his poetry throughout his life. Hughes graduated from Cambridge in 1954. A few years later, in 1956, he co-founded the literary magazine St. Botolph’s Review with a handful of other editors. At the launch party for the magazine, he met Sylvia Plath. A few short months later, on June 16, 1956, they were married.

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is Death of a Naturalist (1966), his first major published volume. Heaney was and is still recognised as one of the principal contributors to poetry in Ireland during his lifetime. American poet Robert Lowell described him as “the most important Irish poet since Yeats”, and many others, including the academic John Sutherland, have said that he was “the greatest poet of our age”. Robert Pinsky has stated that “with his wonderful gift of eye and ear Heaney has the gift of the story-teller.” Upon his death in 2013, The Independent described him as “probably the best-known poet in the world”.

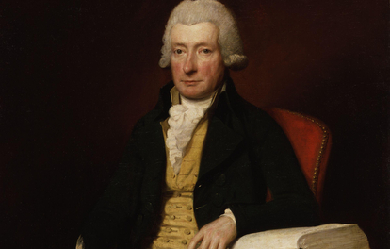

William Cowper (26 November 1731– 25 April 1800) was an English poet and hymnodist. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. In many ways, he was one of the forerunners of Romantic poetry. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called him “the best modern poet”, whilst William Wordsworth particularly admired his poem Yardley-Oak. He was a nephew of the poet Judith Madan.

I was born with verse in my blood. I was raised with poetry mixed in with my mother's milk. We were immersed in poetry from our school days; we were taught to read it, appreciate it, glean wisdom from it, knew all the poets of old by heart...Ironcally, in my culture, writing poetry is the high art and privilege of men seasoned by age and gifted by Creator with this rare talent; it was not for the young to 'fool around' with, so we were not taught or encouraged to express ourselves through verse. So I never knew I had it... It was in my young adulthood that I started to feel the Song of the heart stirring in me. A friend shared with me his poetry, showed me that we all have the capability, if only we tune into ourselves and listen. The first few tentative poems were born from under my pen. Then life happened, I tuned out, forgot that part of myself, shut the door on it for more than a decade. I do not know what prompted for my Song to resurface, one day it just started pouring out of me, but I am grateful for the reawakening of that part of my soul that I'd given up for lost, as well as for the people around me who fuel my inspiration. Whether intentionally or not, they keep the fire burning. An enormous Thank You to all of you for reading, commenting, sharing and inspiring. This is a wonderful and nurturing community for all aspiring poets. Prose is the language of the mind, poetry is the language of the soul.

Richard Le Gallienne (20 January 1866– 15 September 1947) was an English author and poet. The American actress Eva Le Gallienne (1899–1991) was his daughter, by his second marriage. Life and career He was born in Liverpool. He started work in an accountant’s office, but abandoned this job to become a professional writer. The book My Ladies’ Sonnets appeared in 1887, and in 1889 he became, for a brief time, literary secretary to Wilson Barrett. He joined the staff of the newspaper The Star in 1891, and wrote for various papers by the name Logroller. He contributed to The Yellow Book, and associated with the Rhymers’ Club. His first wife, Mildred Lee, died in 1894. They had one daughter, Hesper. In 1897 he married the Danish journalist Julie Norregard, who left him in 1903 and took their daughter Eva to live in Paris. Le Gallienne subsequently became a resident of the United States. He has been credited with the 1906 translation from the Danish of Peter Nansen’s Love’s Trilogy; but most sources and the book itself attribute it to Julie. They were divorced in June 1911. On October 27, 1911, he married Mrs. Irma Perry, née Hinton, whose previous marriage to her first cousin, the painter and sculptor Roland Hinton Perry, had been dissolved in 1904. Le Gallienne and Irma had known each other for some time, and had jointly published an article as early as 1906. Irma’s daughter Gwendolyn Perry subsequently called herself “Gwen Le Gallienne”, but was almost certainly not his natural daughter, having been born in 1900. Le Gallienne and Irma lived in Paris from the late 1920s, where Gwen was by then an established figure in the expatriate bohéme (see, e.g.) and where he wrote a regular newspaper column. Le Gallienne lived in Menton on the French Riviera during the 1940s. During the Second World War Le Gallienne was prevented from returning to his Menton home and lived in Monaco for the rest of the war. Le Gallienne’s house in Menton was occupied by German troops and his library was nearly sent back to Germany as bounty. Le Gallienne appealed to a German officer in Monaco who allowed him to return to Menton to collect his books. During the war Le Gallienne refused to write propaganda for the local German and Italian authorities, and with no income, once collapsed in the street due to hunger. In later times he knew Llewelyn Powys and John Cowper Powys. Asked how to say his name, he told The Literary Digest the stress was “on the last syllable: le gal-i-enn’. As a rule I hear it pronounced as if it were spelled ‘gallion,’ which, of course, is wrong.” (Charles Earle Funk, What’s the Name, Please?, Funk & Wagnalls, 1936.) A number of his works are now available online. He also wrote the foreword to “The Days I Knew” by Lillie Langtry 1925, George H. Doran Company on Murray Hill New York. Works * My Ladies’ Sonnets and Other Vain and Amatorious Verses (1887) * Volumes in Folio (1889) poems * George Meredith: Some Characteristics (1890) * The Book-Bills of Narcissus (1891) * English Poems (1892) * The Religion of a Literary Man (1893) * Robert Louis Stevenson: An Elegy and Other Poems (1895) * Quest of the Golden Girl (1896) novel * Prose Fancies (1896) * Retrospective Reviews (1896) * Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (1897) * If I Were God (1897) * The Romance Of Zion Chapel (1898) * In Praise of Bishop Valentine (1898) * Young Lives (1899) * Sleeping Beauty and Other Prose Fancies (1900) * The Worshipper Of The Image (1900) * The Love Letters of the King, or The Life Romantic (1901) * An Old Country House (1902) * Odes from the Divan of Hafiz (1903) translation * Old Love Stories Retold (1904) * Painted Shadows (1904) * Romances of Old France (1905) * Little Dinners with the Sphinx and other Prose Fancies (1907) * Omar Repentant (1908) * Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde (1909) Translator * Attitudes and Avowals (1910) essays * October Vagabonds (1910) * New Poems (1910) * The Maker of Rainbows and Other Fairy-Tales and Fables (1912) * The Lonely Dancer and Other Poems (1913) * The Highway to Happiness (1913) * Vanishing Roads and Other Essays (1915) * The Silk-Hat Soldier and Other Poems in War Time (1915) * The Chain Invisible (1916) * Pieces of Eight (1918) * The Junk-Man and Other Poems (1920) * A Jongleur Strayed (1922) poems * Woodstock: An Essay (1923) * The Romantic '90s (1925) memoirs * The Romance of Perfume (1928) * There Was a Ship (1930) * From a Paris Garret (1936) memoirs * The Diary of Samuel Pepys (editor) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Le_Gallienne

English Romantic poet John Keats was born on October 31, 1795, in London. The oldest of four children, he lost both his parents at a young age. His father, a livery-stable keeper, died when Keats was eight; his mother died of tuberculosis six years later. After his mother's death, Keats's maternal grandmother appointed two London merchants, Richard Abbey and John Rowland Sandell, as guardians. Abbey, a prosperous tea broker, assumed the bulk of this responsibility, while Sandell played only a minor role. When Keats was fifteen, Abbey withdrew him from the Clarke School, Enfield, to apprentice with an apothecary-surgeon and study medicine in a London hospital. In 1816 Keats became a licensed apothecary, but he never practiced his profession, deciding instead to write poetry.

I am from Cecina in Tuscany, Italy. I moved to Davis, California, in 2009. My life experience in Davis has inspired many of my recent poems. I write my poetry only in Italian language. During the last few summer seasons I have been actively sharing my poems in Tuscany where I participate frequently in cultural and poetry events. As a child, after recognizing that I had a gift for poetry, my parents submitted my work in a variety of different contests. In 1989 I won my first prize. Starting in 1998, I published my poetry in newspapers and magazines, mostly in the area of Tuscany where I was raised. My first book, "Sono un Angelo Dimenticato," was published in 1998 from Ed.La Palma; in 2008 a second book, called "Nessuna Musa di Cristallo” was also published. My poem “Sto per lasciare tutto “(English version: “I’m about to leave everything”) was published in USA, for the Davis Poetry Book 2011. My books: "Extreme Fishing" 2011, "I colori dentro" 2016, both available on Amazon. "Sospesa fra due mondi" was published in Italy by Mds Editore, 2019. In 2020 I moved back to my country and I live in Turin where I work as a teacher.

Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson, CBE (17 February 1864– 5 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the district around Binalong, New South Wales, where he spent much of his childhood. Paterson’s more notable poems include “Waltzing Matilda”, “The Man from Snowy River” and “Clancy of the Overflow”.

Environmental scientist and maybe a poet. I suspect like most people on here I have an urge to write. I've been much buoyed by kind words and likes over the years on this site, despite been in the weeds and not writing for the past few. Now I have my head above the water I can hear my muse again. Thank you kindly for stopping by. I love reading work by others at all stages of their writing journey. Bon Voyage!

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

I started dabbling at age 13, and after a while, I was writing full poems, however, I only have poetry from when I was 16 and up. I am now 28, and I have found that it is so much easier to say things through poetry than it is to verbalize them. I draw inspiration for my poetry from writers, musicians, movies, daily interactions, my faith, and much more. As far as writers go, when I was younger I got introduced to Langston Hughes, and I have learned to take from his style of writing. I also enjoy some good old Shakespeare every once in a while. Most of my influence, however, comes from music; I draw my influence from genres that include but are not limited to, hip-hop, folk, rock, and country. Another thing that really impacts my poetry are events that have taken place in my life. Movie characters and themes also have a chance to have their fair share of influence in my poetry. I am a Christ-follower first and foremost, so, beneath most of my poems stories, there is a spiritual undertone. My plainly faith-based poems, however, are a written (hard) memory of the headspace that I was in at that time in my life. People can create all sorts of art without having to fabricate who they are, and without compromising who they are as a person; it's being able to take from other peoples experiences and write about them, based on the writer's interpretation, that can set a writer apart from others. I write mainly Free Verse poetry, because to me poetry is a lot of self-expression, and if I were to follow the set guidelines of a certain type of poetry, I would then be forfeiting my creative license. Sometimes, however, I like to take from certain styles of poetry, especially when I am trying to convey a particular emotion, for example, I not only write Free Verse but, I also have learned to take from styles, such as Blank Verse & Limericks. I have a friend who said this, "If there is one thing I have learned about writing over the years it is that the best work comes from writing without the audience in mind." I find this quote to be accurate for not only my writing but for writing in general. Love y'all!

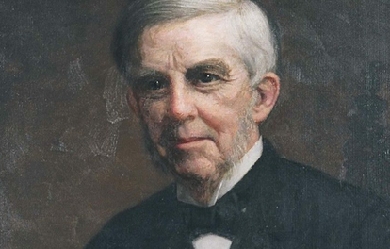

Oliver Wendell Holmes (August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He was also an important medical reformer. In addition to his work as an author and poet, Holmes also served as a physician, professor, lecturer, inventor, and, although he never practiced it, he received formal training in law.

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who came to be known for his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th century and he is often now considered to be among the most important 19th-century poets. His biographer Jonathan Bate states that Clare was "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self”. Early life Clare was born in Helpston, six miles to the north of the city of Peterborough. In his life time, the village was in the Soke of Peterborough in Northamptonshire and his memorial calls him "The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Helpston now lies in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. He became an agricultural labourer while still a child; however, he attended school in Glinton church until he was twelve. In his early adult years, Clare became a pot-boy in the Blue Bell public house and fell in love with Mary Joyce; but her father, a prosperous farmer, forbade her to meet him. Subsequently he was a gardener at Burghley House. He enlisted in the militia, tried camp life with Gypsies, and worked in Pickworth as a lime burner in 1817. In the following year he was obliged to accept parish relief. Malnutrition stemming from childhood may be the main culprit behind his 5-foot stature and may have contributed to his poor physical health in later life. Early poems Clare had bought a copy of Thomson's Seasons and began to write poems and sonnets. In an attempt to hold off his parents' eviction from their home, Clare offered his poems to a local bookseller named Edward Drury. Drury sent Clare's poetry to his cousin John Taylor of the publishing firm of Taylor & Hessey, who had published the work of John Keats. Taylor published Clare's Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820. This book was highly praised, and in the next year his Village Minstrel and other Poems were published. Midlife He had married Martha ("Patty") Turner in 1820. An annuity of 15 guineas from the Marquess of Exeter, in whose service he had been, was supplemented by subscription, so that Clare became possessed of £45 annually, a sum far beyond what he had ever earned. Soon, however, his income became insufficient, and in 1823 he was nearly penniless. The Shepherd's Calendar (1827) met with little success, which was not increased by his hawking it himself. As he worked again in the fields his health temporarily improved; but he soon became seriously ill. Earl FitzWilliam presented him with a new cottage and a piece of ground, but Clare could not settle in his new home. Clare was constantly torn between the two worlds of literary London and his often illiterate neighbours; between the need to write poetry and the need for money to feed and clothe his children. His health began to suffer, and he had bouts of severe depression, which became worse after his sixth child was born in 1830 and as his poetry sold less well. In 1832, his friends and his London patrons clubbed together to move the family to a larger cottage with a smallholding in the village of Northborough, not far from Helpston. However, he felt only more alienated. His last work, the Rural Muse (1835), was noticed favourably by Christopher North and other reviewers, but this was not enough to support his wife and seven children. Clare's mental health began to worsen. As his alcohol consumption steadily increased along with his dissatisfaction with his own identity, Clare's behaviour became more erratic. A notable instance of this behaviour was demonstrated in his interruption of a performance of The Merchant of Venice, in which Clare verbally assaulted Shylock. He was becoming a burden to Patty and his family, and in July 1837, on the recommendation of his publishing friend, John Taylor, Clare went of his own volition (accompanied by a friend of Taylor's) to Dr Matthew Allen's private asylum High Beach near Loughton, in Epping Forest. Taylor had assured Clare that he would receive the best medical care. Later life and death During his first few asylum years in Essex (1837–1841), Clare re-wrote famous poems and sonnets by Lord Byron. His own version of Child Harold became a lament for past lost love, and Don Juan, A Poem became an acerbic, misogynistic, sexualised rant redolent of an aging Regency dandy. Clare also took credit for Shakespeare's plays, claiming to be the Renaissance genius himself. "I'm John Clare now," the poet claimed to a newspaper editor, "I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly." In 1841, Clare left the asylum in Essex, to walk home, believing that he was to meet his first love Mary Joyce; Clare was convinced that he was married with children to her and Martha as well. He did not believe her family when they told him she had died accidentally three years earlier in a house fire. He remained free, mostly at home in Northborough, for the five months following, but eventually Patty called the doctors in. Between Christmas and New Year in 1841, Clare was committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum (now St Andrew's Hospital). Upon Clare's arrival at the asylum, the accompanying doctor, Fenwick Skrimshire, who had treated Clare since 1820, completed the admission papers. To the enquiry "Was the insanity preceded by any severe or long-continued mental emotion or exertion?", Dr Skrimshire entered: "After years of poetical prosing." He remained here for the rest of his life under the humane regime of Dr Thomas Octavius Prichard, encouraged and helped to write. Here he wrote possibly his most famous poem, I Am. He died on 20 May 1864, in his 71st year. His remains were returned to Helpston for burial in St Botolph’s churchyard. Today, children at the John Clare School, Helpston's primary, parade through the village and place their 'midsummer cushions' around Clare's gravestone (which has the inscriptions "To the Memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet" and "A Poet is Born not Made") on his birthday, in honour of their most famous resident. The thatched cottage where he was born was bought by the John Clare Education & Environment Trust in 2005 and is restoring the cottage to its 18th century state. Poetry In his time, Clare was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Since his formal education was brief, Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography in his poetry and prose. Many of his poems would come to incorporate terms used locally in his Northamptonshire dialect, such as 'pooty' (snail), 'lady-cow' (ladybird), 'crizzle' (to crisp) and 'throstle' (song thrush). In his early life he struggled to find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He also felt that he did not belong with other peasants. Clare once wrote "I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.” It is common to see an absence of punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with his editors about how it should be presented to the public. Clare grew up during a period of massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted, the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches 'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to my forefathers I am content." His early work delights both in nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as Winter Evening, Haymaking and Wood Pictures in Summer celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as Little Trotty Wagtail show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badger shows his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet. His later poetry tends to be more meditative and use forms similar to the folks songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening. His knowledge of the natural world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as I Am show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of linguistics. His 'bird's nest poems', it can be argued, illustrate the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth to practice in an older style. Revival of interest in the twentieth century Clare was relatively forgotten during the later nineteenth century, but interest in his work was revived by Arthur Symons in 1908, Edmund Blunden in 1920 and John and Anne Tibble in their ground-breaking 1935 2-volume edition. Benjamin Britten set some of 'May' from A Shepherd's Calendar in his Spring Symphony of 1948, and included a setting of The Evening Primrose in his Five Flower Songs Copyright to much of his work has been claimed since 1965 by the editor of the Complete Poetry (OUP, 9 vols., 1984–2003), Professor Eric Robinson though these claims were contested. Recent publishers have refused to acknowledge the claim (especially in recent editions from Faber and Carcanet) and it seems the copyright is now defunct. The John Clare Trust purchased Clare Cottage in Helpston in 2005, preserving it for future generations. In May 2007 the Trust gained £1.m of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and commissioned Jefferson Sheard Architects to create the new landscape design and Visitor Centre, including a cafe, shop and exhibition space. The Cottage has been restored using traditional building methods and opened to the public. The largest collection of original Clare manuscripts are housed at Peterborough Museum, where they are available to view by appointment. Since 1993, the John Clare Society of North America has organised an annual session of scholarly papers concerning John Clare at the annual Convention of the Modern Language Association of America. Poetry collections by Clare (chronological) * Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. London, 1820. * The Village Minstrel, and Other Poems. London, 1821. * The Shepherd's Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems. London, 1827 * The Rural Muse. London, 1835. * Sonnet. London 1841 * First Love * Snow Storm. * The Firetail. * The Badger – Time unknown References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clare

I've been in a serious relationship for 11yrs now, with my Sweetie-pie. We met @ a club in Lafayette, LA, called Jules. A local gay bar, that was in the heart of downtown, but alas it shut down shortly after we met. I always think of Fate having a hand in our meeting, because I had sent my longing for a love to love into the universe & wasn't looking to fall in love when we met. Also I had just driven 8+ hrs from West Texas after visiting relatives & didn't plan on going out. But for some reason I felt the urge to get my dance on & wallah! The rest is history. I get asked quite often about my nationality, but it comes out wrong like ppl asking "what are you" for which I reply "human & you?" So for those of you curious of my nationality/ethnicity I'm Panamanian, Mexican, African-American & Blackfoot Native American. My mom claims she's got Apache blood as well, but it's just her belief (yet to be confirmed). My grandparents on my mom's side are Swedish & Norwegian, so yeah, my family looks like the League of Nations if you were to see us all gathered at a family reunion. A fitting rainbow of nationalities. UPDATE! It's been years since I've updated my profile. fast forward 7yrs later and I currently am selling crystals on Etsy @skyygems. Im now living in Houston, TX, still with my love whom I met at that club all those yrs ago. We have a miniature poodle named Ford (my sweetie's doing, I wasn't feeling that name) and we are now enjoying downtown living.

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's view, were responsible for a vainglorious war. He later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston Trilogy". Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the British Army just as the threat of World War I was realised, and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry on the day the United Kingdom declared war (4 August 1914). He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing.

These are writings from the inner workings of a mind in constant thought about LIFE and everything it entails for the purpose of self-transcendence and with the intention to bring more understanding and healing to my own life and possibly those of others. My journey is one of self-exploration and discovery. Since my beliefs lie on the premise that we are so strongly connected to everything in existence, in getting to know myself I am getting to know the world. Learning about the world teaches me about myself. I find freedom in understanding and expression. My one true love is the paradox of questioning existence.