Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

.jpg)

One that knows about the beauty of simplicity. Although giving up to the temptation of complexity, severing the link with the eventual reader. As time allows I'll post brief explanations of knots and obscure references that were not avoided. Not a fan of editing, outside real English native speakers reality. So pardon me for all artificiality. I am trying to make amends to my native language, an ongoing project. As English literature is concerned and especially American, British and Irish poetry... I love it. Beyond any regret, written words may conflict with the spirit of times. I don't aspire, rather transpire toxic thoughts, beauty feeds equilibrium. Ethics and principles, hope and resilience. I see that bucket of Web Dubois. Subtle take over that I never thought possible twenty years ago, on the turn of 20th century, full of lessons turned into caricatures by a cold underlying, unrevealed power(s). And yet, "quality of life" has never been higher, even for "the dispossessed". Looking closely, hearing whispers returning, how would I like to live other people's lives, to ascertain facts and legends. Pace of life, mythologic infinity, eradicated impossible. Maybe. But if here remains even one "pico of doubt"...( maybe not). For those who read strange portuguese...one exemple infra. https://www.escritas.org/pt/n/mgenthbjpafa21 (credits: yukino_neko_girl_anime_star_wreath. Congrats for the art.)

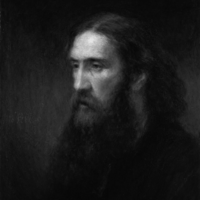

Khalil Gibran (Arabic pronunciation: [xaˈliːl ʒiˈbrɑːn]) (January 6, 1883 - April 10, 1931); born Gubran Khalil Gubran, was a Lebanese-American artist, poet, and writer. Born in the town of Bsharri in modern-day Lebanon (then part of the Ottoman Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate), as a young man he emigrated with his family to the United States where he studied art and began his literary career. In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a literary and political rebel. His Romantic style was at the heart of a renaissance in modern Arabic literature, especially prose poetry, breaking away from the classical school. In Lebanon, he is still celebrated as a literary hero. He is chiefly known in the English-speaking world for his 1923 book The Prophet, an early example of inspirational fiction including a series of philosophical essays written in poetic English prose. The book sold well despite a cool critical reception, gaining popularity in the 1930s and again especially in the 1960s counterculture. Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu. In academic contexts his name is often spelled Jubrān Khalīl Jubrān,:217:255 Jibrān Khalīl Jibrān,:217:559 or Jibrān Xalīl Jibrān;:189 Arabic جبران خليل جبران , January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931) also known as Kahlil Gibran, In Lebanon Gibran was born to a Maronite Catholic family from the historical town of Bsharri in northern Lebanon. His mother Kamila, daughter of a priest, was thirty when he was born; his father Khalil was her third husband. As a result of his family's poverty, Gibran received no formal schooling during his youth. However, priests visited him regularly and taught him about the Bible, as well as the Arabic and Syriac languages. Gibran's father initially worked in an apothecary but, with gambling debts he was unable to pay, he went to work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator. Around 1891, extensive complaints by angry subjects led to the administrator being removed and his staff being investigated. Gibran's father was imprisoned for embezzlement, and his family's property was confiscated by the authorities. Kamila Gibran decided to follow her brother to the United States. Although Gibran's father was released in 1894, Kamila remained resolved and left for New York on June 25, 1895, taking Khalil, his younger sisters Mariana and Sultana, and his elder half-brother Peter (in Arabic, Butrus). In the United States The Gibrans settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second largest Syrian/Lebanese-American community in the United States. Due to a mistake at school, he was registered as Kahlil Gibran. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door to door. Gibran started school on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at a nearby settlement house. Through his teachers there, he was introduced to the avant-garde Boston artist, photographer, and publisher Fred Holland Day, who encouraged and supported Gibran in his creative endeavors. A publisher used some of Gibran's drawings for book covers in 1898. Gibran's mother, along with his elder brother Peter, wanted him to absorb more of his own heritage rather than just the Western aesthetic culture he was attracted to, so at the age of fifteen, Gibran returned to his homeland to study at a Maronite-run preparatory school and higher-education institute in Beirut, called Al-Hikma (The Wisdom). He started a student literary magazine with a classmate and was elected "college poet". He stayed there for several years before returning to Boston in 1902, coming through Ellis Island (a second time) on May 10. Two weeks before he got back, his sister Sultana died of tuberculosis at the age of 14. The next year, Peter died of the same disease and his mother died of cancer. His sister Marianna supported Gibran and herself by working at a dressmaker’s shop. Art and poetry Gibran held his first art exhibition of his drawings in 1904 in Boston, at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Elizabeth Haskell, a respected headmistress ten years his senior. The two formed an important friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran’s life. Though publicly discreet, their correspondence reveals that the two were lovers. In fact, Gibran twice proposed to her but marriage was not possible in the face of her family's conservatism. Haskell influenced not only Gibran’s personal life, but also his career. She became his editor, and introduced him to Charlotte Teller, a journalist,and Emilie Michel (Micheline), a French teacher, who accepted to pose for him as a model and became close friends. In 1908, Gibran went to study art in Paris for two years. While there he met his art study partner and lifelong friend Youssef Howayek. While most of Gibran's early writings were in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. His first book for the publishing company Alfred A. Knopf, in 1918, was The Madman, a slim volume of aphorisms and parables written in biblical cadence somewhere between poetry and prose. Gibran also took part in the New York Pen League, also known as the "immigrant poets" (al-mahjar), alongside important Lebanese-American authors such as Ameen Rihani, Elia Abu Madi and Mikhail Naimy, a close friend and distinguished master of Arabic literature, whose descendants Gibran declared to be his own children, and whose nephew, Samir, is a godson of Gibran's. Much of Gibran's writings deal with Christianity, especially on the topic of spiritual love. But his mysticism is a convergence of several different influences : Christianity, Islam, Sufism, Hinduism and theosophy. He wrote : "You are my brother and I love you. I love you when you prostrate yourself in your mosque, and kneel in your church and pray in your synagogue. You and I are sons of one faith - the Spirit." Juliet Thompson, one of Gibran's acquaintances, reported several anecdotes relating to Gibran: She recalls Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá, the leader of the Bahá’í Faith at the time of his visit to the United States, circa 1911–1912. Barbara Young, in "This Man from Lebanon: A Study of Khalil Gibran", records Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting `Abdu'l-Bahá who sat for a pair of portraits. Thompson reports Gibran saying that all the way through writing of "Jesus, The Son of Man", he thought of `Abdu'l-Bahá. Years later, after the death of `Abdu'l-Bahá, there was a viewing of the movie recording of `Abdu'l-Bahá – Gibran rose to talk and in tears, proclaimed an exalted station of `Abdu'l-Bahá and left the event weeping. His poetry is notable for its use of formal language, as well as insights on topics of life using spiritual terms. Gibran's best-known work is The Prophet, a book composed of twenty-six poetic essays. Its popularity grew markedly during the 1960s with the American counterculture and then with the flowering of the New Age movements. It has remained popular with these and with the wider population to this day. Since it was first published in 1923, The Prophet has never been out of print. Having been translated into more than forty languages, it was one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century in the United States. One of his most notable lines of poetry is from "Sand and Foam" (1926), which reads: "Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you". This line was used by John Lennon and placed, though in a slightly altered form, into the song "Julia" from The Beatles' 1968 album The Beatles (a.k.a. "The White Album”). Drawing and painting Gibran was an accomplished artist, especially in drawing and watercolour, having attended art school in Paris from 1908 to 1910, pursuing a symbolist and romantic style over then up-and-coming realism. His more than 700 images include portraits of his friends WB Yeats, Carl Jung and August Rodin. A possible Gibran painting was the subject of a June 2012 episode of the PBS TV series History Detectives. Political thought Gibran was by no means a politician. He used to say : "I am not a politician, nor do I wish to become one" and "Spare me the political events and power struggles, as the whole earth is my homeland and all men are my fellow countrymen". Nevertheless, Gibran called for the adoption of Arabic as a national language of Syria, considered from a geographic point of view, not as a political entity. When Gibran met `Abdu'l-Bahá in 1911–12, who traveled to the United States partly to promote peace, Gibran admired the teachings on peace but argued that "young nations like his own" be freed from Ottoman control. Gibran also wrote the famous "Pity The Nation" poem during these years, posthumously published in The Garden of the Prophet. When the Ottomans were finally driven out of Syria during World War I, Gibran's exhilaration was manifested in a sketch called "Free Syria" which appeared on the front page of al-Sa'ih's special "victory" edition. Moreover, in a draft of a play, still kept among his papers, Gibran expressed great hope for national independence and progress. This play, according to Khalil Hawi, "defines Gibran's belief in Syrian nationalism with great clarity, distinguishing it from both Lebanese and Arab nationalism, and showing us that nationalism lived in his mind, even at this late stage, side by side with internationalism.” Death and legacy Gibran died in New York City on April 10, 1931: the cause was determined to be cirrhosis of the liver and tuberculosis. Before his death, Gibran expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. This wish was fulfilled in 1932, when Mary Haskell and his sister Mariana purchased the Mar Sarkis Monastery in Lebanon, which has since become the Gibran Museum. The words written next to Gibran's grave are "a word I want to see written on my grave: I am alive like you, and I am standing beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you ...." Gibran willed the contents of his studio to Mary Haskell. There she discovered her letters to him spanning twenty-three years. She initially agreed to burn them because of their intimacy, but recognizing their historical value she saved them. She gave them, along with his letters to her which she had also saved, to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library before she died in 1964. Excerpts of the over six hundred letters were published in "Beloved Prophet" in 1972. Mary Haskell Minis (she wed Jacob Florance Minis in 1923) donated her personal collection of nearly one hundred original works of art by Gibran to the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia in 1950. Haskell had been thinking of placing her collection at the Telfair as early as 1914. In a letter to Gibran, she wrote "I am thinking of other museums ... the unique little Telfair Gallery in Savannah, Ga., that Gari Melchers chooses pictures for. There when I was a visiting child, form burst upon my astonished little soul." Haskell's gift to the Telfair is the largest public collection of Gibran’s visual art in the country, consisting of five oils and numerous works on paper rendered in the artist’s lyrical style, which reflects the influence of symbolism. The future American royalties to his books were willed to his hometown of Bsharri, to be "used for good causes”. Works In Arabic: * Nubthah fi Fan Al-Musiqa (Music, 1905) * Ara'is al-Muruj (Nymphs of the Valley, also translated as Spirit Brides and Brides of the Prairie, 1906) * al-Arwah al-Mutamarrida (Rebellious Spirits, 1908) * al-Ajniha al-Mutakassira (Broken Wings, 1912) * Dam'a wa Ibtisama (A Tear and A Smile, 1914) * al-Mawakib (The Processions, 1919) * al-‘Awāsif (The Tempests, 1920) * al-Bada'i' waal-Tara'if (The New and the Marvellous, 1923) In English, prior to his death: * The Madman (1918) (downloadable free version) * Twenty Drawings (1919) * The Forerunner (1920) * The Prophet, (1923) * Sand and Foam (1926) * Kingdom of the Imagination (1927) * Jesus, The Son of Man (1928) * The Earth Gods (1931) Posthumous, in English: * The Wanderer (1932) * The Garden of the Prophet (1933, Completed by Barbara Young) * Lazarus and his Beloved (Play, 1933) Collections: * Prose Poems (1934) * Secrets of the Heart (1947) * A Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1951) * A Self-Portrait (1959) * Thoughts and Meditations (1960) * A Second Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1962) * Spiritual Sayings (1962) * Voice of the Master (1963) * Mirrors of the Soul (1965) * Between Night & Morn (1972) * A Third Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1975) * The Storm (1994) * The Beloved (1994) * The Vision (1994) * Eye of the Prophet (1995) * The Treasured Writings of Kahlil Gibran (1995) Other: * Beloved Prophet, The love letters of Khalil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and her private journal (1972, edited by Virginia Hilu) Memorials and honors * Lebanese Ministry of Post and Telecommunications published a stamp in his honor in 1971. * Gibran Museum in Bsharri, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden, Beirut, Lebanon * Gibran Khalil Gibran collectin, Soumaya Museum, Mexico. * Kahlil Gibran Street, Ville Saint-Laurent, Quebec, Canada inaugurated on 27 Sept. 2008 on occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth. * Gibran Kahlil Gibran Skiing Piste, The Cedars Ski Resort, Lebanon * Kahlil Gibran Memorial Garden in Washington, D.C., dedicated in 1990 * The Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace, University of Maryland, currently held by Suheil Bushrui * Pavilion K. Gibran at École Pasteur in Montréal, Quebec, Canada * Gibran Memorial Plaque in Copley Square, Boston, Massachusetts see Kahlil Gibran (sculptor). * Khalil Gibran International Academy, a public high school in Brooklyn, NY, opened in September 2007 * Khalil Gibran Park (Parcul Khalil Gibran) in Bucharest, Romania * Gibran Kalil Gibran sculpture on a marble pedestal indoors at Arab Memorial building at Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil * Gibran Khalil Gibran Memorial, in front of Plaza de las Naciones. Buenos Aires. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khalil_Gibran

_and_brother_Ronald_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

George MacDonald (10 December 1824– 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet, and Christian minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll. His writings have been cited as a major literary influence by many notable authors including W. H. Auden, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, E. Nesbit and Madeleine L’Engle. C. S. Lewis wrote that he regarded MacDonald as his “master”: “Picking up a copy of Phantastes one day at a train-station bookstall, I began to read. A few hours later,” said Lewis, “I knew that I had crossed a great frontier.” G. K. Chesterton cited The Princess and the Goblin as a book that had “made a difference to my whole existence”. Elizabeth Yates wrote of Sir Gibbie, “It moved me the way books did when, as a child, the great gates of literature began to open and first encounters with noble thoughts and utterances were unspeakably thrilling.” Even Mark Twain, who initially disliked MacDonald, became friends with him, and there is some evidence that Twain was influenced by MacDonald. Christian author Oswald Chambers (1874–1917) wrote in Christian Disciplines, vol. 1, (pub. 1934) that “it is a striking indication of the trend and shallowness of the modern reading public that George MacDonald’s books have been so neglected”. In addition to his fairy tales, MacDonald wrote several works on Christian apologetics including several that defended his view of Christian Universalism. Early life George MacDonald was born on 10 December 1824 at Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. His father, a farmer, was one of the MacDonalds of Glen Coe, and a direct descendant of one of the families that suffered in the massacre of 1692. The Doric dialect of the Aberdeenshire area appears in the dialogue of some of his non-fantasy novels. MacDonald grew up in the Congregational Church, with an atmosphere of Calvinism. But MacDonald never felt comfortable with some aspects of Calvinist doctrine; indeed, legend has itt that when the doctrine of predestination was first explained to him, he burst into tears (although assured that he was one of the elect). Later novels, such as Robert Falconer and Lilith, show a distaste for the idea that God’s electing love is limited to some and denied to others. MacDonald graduated from the University of Aberdeen, and then went to London, studying at Highbury College for the Congregational ministry. In 1850 he was appointed pastor of Trinity Congregational Church, Arundel, but his sermons (preaching God’s universal love and the possibility that none would, ultimately, fail to unite with God) met with little favour and his salary was cut in half. Later he was engaged in ministerial work in Manchester. He left that because of poor health, and after a short sojourn in Algiers he settled in London and taught for some time at the University of London. MacDonald was also for a time editor of Good Words for the Young, and lectured successfully in the United States during 1872–1873. Work George MacDonald’s best-known works are Phantastes, The Princess and the Goblin, At the Back of the North Wind, and Lilith, all fantasy novels, and fairy tales such as “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and “The Wise Woman”. “I write, not for children,” he wrote, “but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.” MacDonald also published some volumes of sermons, the pulpit not having proved an unreservedly successful venue. MacDonald also served as a mentor to Lewis Carroll (the pen-name of Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson); it was MacDonald’s advice, and the enthusiastic reception of Alice by MacDonald’s many sons and daughters, that convinced Carroll to submit Alice for publication. Carroll, one of the finest Victorian photographers, also created photographic portraits of several of the MacDonald children. MacDonald was also friends with John Ruskin and served as a go-between in Ruskin’s long courtship with Rose La Touche. MacDonald was acquainted with most of the literary luminaries of the day; a surviving group photograph shows him with Tennyson, Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Trollope, Ruskin, Lewes, and Thackeray. While in America he was a friend of Longfellow and Walt Whitman. In 1877 he was given a civil list pension. From 1879 he and his family moved to Bordighera in a place much loved by British expatriates, the Riviera dei Fiori in Liguria, Italy, almost on the French border. In that locality there also was an Anglican Church, which he attended. Deeply enamoured of the Riviera, he spent there 20 years, writing almost half of his whole literary production, especially the fantasy work. In that Ligurian town MacDonald founded a literary studio named Casa Coraggio (Bravery House), which soon became one of the most renowned cultural centres of that period, well attended by British and Italian travellers, and by locals. In that house representations were often held of classic plays, and readings were given of Dante and Shakespeare. In 1900 he moved into St George’s Wood, Haslemere, a house designed for him by his son, Robert Falconer MacDonald, and the building overseen by his eldest son, Greville MacDonald. He died on 18 September 1905 in Ashtead, (Surrey). He was cremated and his ashes buried in Bordighera, in the English cemetery, along with his wife Louisa and daughters Lilia and Grace. As hinted above, MacDonald’s use of fantasy as a literary medium for exploring the human condition greatly influenced a generation of such notable authors as C. S. Lewis (who featured him as a character in his The Great Divorce), J. R. R. Tolkien, and Madeleine L’Engle. MacDonald’s non-fantasy novels, such as Alec Forbes, had their influence as well; they were among the first realistic Scottish novels, and as such MacDonald has been credited with founding the “kailyard school” of Scottish writing. His son Greville MacDonald became a noted medical specialist, a pioneer of the Peasant Arts movement, and also wrote numerous fairy tales for children. Greville ensured that new editions of his father’s works were published. Another son, Ronald MacDonald, was also a novelist. Ronald’s son, Philip MacDonald, (George MacDonald’s grandson) became a very well known Hollywood screenwriter. Theology MacDonald rejected the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement as developed by John Calvin, which argues that Christ has taken the place of sinners and is punished by the wrath of God in their place, believing that in turn it raised serious questions about the character and nature of God. Instead, he taught that Christ had come to save people from their sins, and not from a Divine penalty for their sins. The problem was not the need to appease a wrathful God but the disease of cosmic evil itself. George MacDonald frequently described the Atonement in terms similar to the Christus Victor theory. MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “Did he not foil and slay evil by letting all the waves and billows of its horrid sea break upon him, go over him, and die without rebound—spend their rage, fall defeated, and cease? Verily, he made atonement!” MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, “I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children.” MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, “When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?” He replied, “No. As much as they fear will come upon them, possibly far more.... The wrath will consume what they call themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear.” However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald’s optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see universal reconciliation). He recognised the theoretical possibility that, bathed in the eschatological divine light, some might perceive right and wrong for what they are but still refuse to be transfigured by operation of God’s fires of love, but he did not think this likely. In this theology of divine punishment, MacDonald stands in opposition to Augustine of Hippo, and in agreement with the Greek Church Fathers Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and St. Gregory of Nyssa, although it is unknown whether MacDonald had a working familiarity with Patristics or Eastern Orthodox Christianity. At least an indirect influence is likely, because F. D. Maurice, who influenced MacDonald, knew the Greek Fathers, especially Clement, very well. MacDonald states his theological views most distinctly in the sermon Justice found in the third volume of Unspoken Sermons. In his introduction to George MacDonald: An Anthology, C. S. Lewis speaks highly of MacDonald’s theology: “This collection, as I have said, was designed not to revive MacDonald’s literary reputation but to spread his religious teaching. Hence most of my extracts are taken from the three volumes of Unspoken Sermons. My own debt to this book is almost as great as one man can owe to another: and nearly all serious inquirers to whom I have introduced it acknowledge that it has given them great help—sometimes indispensable help toward the very acceptance of the Christian faith. ... I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself. Hence his Christ-like union of tenderness and severity. Nowhere else outside the New Testament have I found terror and comfort so intertwined.... In making this collection I was discharging a debt of justice. I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master; indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it.” Bibliography Fantasy * Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858) * “Cross Purposes” (1862) * Adela Cathcart (1864), containing “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories * The Portent: A Story of the Inner Vision of the Highlanders, Commonly Called “The Second Sight” (1864) * Dealings with the Fairies (1867), containing “The Golden Key”, “The Light Princess”, “The Shadows”, and other short stories * At the Back of the North Wind (1871) * Works of Fancy and Imagination (1871), including Within and Without, “Cross Purposes”, “The Light Princess”, “The Golden Key”, and other works * The Princess and the Goblin (1872) * The Wise Woman: A Parable (1875) (Published also as “The Lost Princess: A Double Story”; or as “A Double Story”.) * The Gifts of the Child Christ and Other Tales (1882; republished as Stephen Archer and Other Tales) * The Day Boy and the Night Girl (1882) * The Princess and Curdie (1883), a sequel to The Princess and the Goblin * The Flight of the Shadow (1891) * Lilith: A Romance (1895) Realistic fiction * David Elginbrod (1863; republished as The Tutor’s First Love), originally published in three volumes * Alec Forbes of Howglen (1865; republished as The Maiden’s Bequest) * Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood (1867) * Guild Court: A London Story (1868) * Robert Falconer (1868; republished as The Musician’s Quest) * The Seaboard Parish (1869), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood * Ranald Bannerman’s Boyhood (1871) * Wilfrid Cumbermede (1871–72) * The Vicar’s Daughter (1871–72), a sequel to Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood and The Seaboard Parish * The History of Gutta Percha Willie, the Working Genius (1873), usually called simply Gutta Percha Willie * Malcolm (1875) * St. George and St. Michael (1876) * Thomas Wingfold, Curate (1876; republished as The Curate’s Awakening) * The Marquis of Lossie (1877; republished as The Marquis’ Secret), the second book of Malcolm * Paul Faber, Surgeon (1879; republished as The Lady’s Confession), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate * Sir Gibbie (1879; republished as The Baronet’s Song) * Mary Marston (1881; republished as A Daughter’s Devotion) * Warlock o’ Glenwarlock (1881; republished as Castle Warlock and The Laird’s Inheritance) * Weighed and Wanting (1882; republished as A Gentlewoman’s Choice) * Donal Grant (1883; republished as The Shepherd’s Castle), a sequel to Sir Gibbie * What’s Mine’s Mine (1886; republished as The Highlander’s Last Song) * Home Again: A Tale (1887; republished as The Poet’s Homecoming) * The Elect Lady (1888; republished as The Landlady’s Master) * A Rough Shaking (1891) * There and Back (1891; republished as The Baron’s Apprenticeship), a sequel to Thomas Wingfold, Curate and Paul Faber, Surgeon * Heather and Snow (1893; republished as The Peasant Girl’s Dream) * Salted with Fire (1896; republished as The Minister’s Restoration) * Far Above Rubies (1898) Poetry * Twelve of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis (1851), privately printed translation of the poetry of Novalis * Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem (1855) * Poems (1857) * “A Hidden Life” and Other Poems (1864) * “The Disciple” and Other Poems (1867) * Exotics: A Translation of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis, the Hymn-book of Luther, and Other Poems from the German and Italian (1876) * Dramatic and Miscellaneous Poems (1876) * Diary of an Old Soul (1880) * A Book of Strife, in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul (1880), privately printed * The Threefold Cord: Poems by Three Friends (1883), privately printed, with Greville Matheson and John Hill MacDonald * Poems (1887) * The Poetical Works of George MacDonald, 2 Volumes (1893) * Scotch Songs and Ballads (1893) * Rampolli: Growths from a Long-planted Root (1897) Nonfiction * Unspoken Sermons (1867) * England’s Antiphon (1868, 1874) * The Miracles of Our Lord (1870) * Cheerful Words from the Writing of George MacDonald (1880), compiled by E. E. Brown * Orts: Chiefly Papers on the Imagination, and on Shakespeare (1882) * “Preface” (1884) to Letters from Hell (1866) by Valdemar Adolph Thisted * The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke: A Study With the Test of the Folio of 1623 (1885) * Unspoken Sermons, Second Series (1885) * Unspoken Sermons, Third Series (1889) * A Cabinet of Gems, Cut and Polished by Sir Philip Sidney; Now, for the More Radiance, Presented Without Their Setting by George MacDonald (1891) * The Hope of the Gospel (1892) * A Dish of Orts (1893) * Beautiful Thoughts from George MacDonald (1894), compiled by Elizabeth Dougall In popular culture * (Alphabetical by artist) * Christian celtic punk band Ballydowse have a song called “George MacDonald” on their album Out of the Fertile Crescent. The song is both taken from MacDonald’s poem “My Two Geniuses” and liberally quoted from Phantastes. * American classical composer John Craton has utilized several of MacDonald’s stories in his works, including “The Gray Wolf” (in a tone poem of the same name for solo mandolin– 2006) and portions of “The Cruel Painter”, Lilith, and The Light Princess (in Three Tableaux from George MacDonald for mandolin, recorder, and cello– 2011). * Contemporary new-age musician Jeff Johnson wrote a song titled “The Golden Key” based on George MacDonald’s story of the same name. He has also written several other songs inspired by MacDonald and the Inklings. * Jazz pianist and recording artist Ray Lyon has a song on his CD Beginning to See (2007), called “Up The Spiral Stairs”, which features lyrics from MacDonald’s 26 and 27 September devotional readings from the book Diary of an Old Soul. * A verse from The Light Princess is cited in the “Beauty and the Beast” song by Nightwish. * Rock group The Waterboys titled their album Room to Roam (1990) after a passage in MacDonald’s Phantastes, also found in Lilith. The title track of the album comprises a MacDonald poem from the text of Phantastes set to music by the band. The novels Lilith and Phantastes are both named as books in a library, in the title track of another Waterboys album, Universal Hall (2003). (The Waterboys have also quoted from C. S. Lewis in several songs, including “Church Not Made With Hands” and “Further Up, Further In”, confirming the enduring link in modern pop culture between MacDonald and Lewis.) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_MacDonald

"Life imitates Art, far more than Art imitates life". Hi, my name is Laila.. I love everything in Arts, I think Nature is the most beautiful thing humanity is blessed with. I love looking at the vast sky and the ocean because, for a moment it reminds me that society is small and I can create my own system/ pieces of art that doesn't need to fall in place with the norms the the system created. I write, yes, it's kind of something I kind of find solace in.. Delilah, my pen name. An entire different shade of me comes out when I am left with a notebook and pen.. Spilling ink has always been a part of me.. Uh.. I believe that kindness is the most beautiful of qualities one could have... You don't have to be rich or famous to be beautiful... You just have to have a... heart filled with empathy, love, compassion, humility and most of all.. Kindness. And then you are... Beautiful. For true beauty comes from within.. I'm 18 years old, currently a student, studying to be an English teacher. And very very nervous when it comes to speaking in front of a class... #confessions.. 2016 - There's plenty I'd like to state that just has that.. 'Wow' effect, I think the best word for this would be, Yūgen. Something about this world, this experience. To watch the Sun sink behind a hill and wait for the light of the stars. To wander into the unknown without reason or return. To watch trees sway and the colour of Autumn fall. To trace your fingers on your once so dearly beloved's hand and know all the routes on it yet... still not know that it was the last time you would touch them. To contemplate the paths of the birds across the vast sky and around the sun, and so, we have been.. Turned. xxxxx I tend to isolate myself sometimes... don't worry, Nothing is wrong, it's just the way I am, I find it more.... meaningful, as I go through different perspectives... .................( uhhhhh... Figuring out Where's Never land ... ^_^) ........ Anyway, Thank you! for going though my work... Cuidate!... Take care! Delilah Instagram : @of.blue.heart.waves.x

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869– 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. His most famous work, For the Fallen, is well known for being used in Remembrance Sunday services. Pre-war life Laurence Binyon was born in Lancaster, Lancashire, England. His parents were Frederick Binyon, and Mary Dockray. Mary’s father, Robert Benson Dockray, was the main engineer of the London and Birmingham Railway. The family were Quakers. Binyon studied at St Paul’s School, London. Then he read Classics (Honour Moderations) at Trinity College, Oxford, where he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1891. Immediately after graduating in 1893, Binyon started working for the Department of Printed Books of the British Museum, writing catalogues for the museum and art monographs for himself. In 1895 his first book, Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century, was published. In that same year, Binyon moved into the Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, under Campbell Dodgson. In 1909, Binyon became its Assistant Keeper, and in 1913 he was made the Keeper of the new Sub-Department of Oriental Prints and Drawings. Around this time he played a crucial role in the formation of Modernism in London by introducing young Imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington and H.D. to East Asian visual art and literature. Many of Binyon’s books produced while at the Museum were influenced by his own sensibilities as a poet, although some are works of plain scholarship– such as his four-volume catalogue of all the Museum’s English drawings, and his seminal catalogue of Chinese and Japanese prints. In 1904 he married historian Cicely Margaret Powell, and the couple had three daughters. During those years, Binyon belonged to a circle of artists, as a regular patron of the Wiener Cafe of London. His fellow intellectuals there were Ezra Pound, Sir William Rothenstein, Walter Sickert, Charles Ricketts, Lucien Pissarro and Edmund Dulac. Binyon’s reputation before the war was such that, on the death of the Poet Laureate Alfred Austin in 1913, Binyon was among the names mentioned in the press as his likely successor (others named included Thomas Hardy, John Masefield and Rudyard Kipling; the post went to Robert Bridges). For the Fallen Moved by the opening of the Great War and the already high number of casualties of the British Expeditionary Force, in 1914 Laurence Binyon wrote his For the Fallen, with its Ode of Remembrance, as he was visiting the cliffs on the north Cornwall coast, either at Polzeath or at Portreath (at each of which places there is a plaque commemorating the event, though Binyon himself mentioned Polzeath in a 1939 interview. The confusion may be related to Porteath Farm being near Polzeath). The piece was published by The Times newspaper in September, when public feeling was affected by the recent Battle of Marne. Today Binyon’s most famous poem, For the Fallen, is often recited at Remembrance Sunday services in the UK; is an integral part of Anzac Day services in Australia and New Zealand and of the 11 November Remembrance Day services in Canada. The third and fourth verses of the poem (although often just the fourth) have thus been claimed as a tribute to all casualties of war, regardless of nation. They went with songs to the battle, they were young. Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, We will remember them. They mingle not with their laughing comrades again; They sit no more at familiar tables of home; They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; They sleep beyond England’s foam Three of Binyon’s poems, including “For the Fallen”, were set by Sir Edward Elgar in his last major orchestra/choral work, The Spirit of England. In 1915, despite being too old to enlist in the First World War, Laurence Binyon volunteered at a British hospital for French soldiers, Hôpital Temporaire d’Arc-en-Barrois, Haute-Marne, France, working briefly as a hospital orderly. He returned in the summer of 1916 and took care of soldiers taken in from the Verdun battlefield. He wrote about his experiences in For Dauntless France (1918) and his poems, “Fetching the Wounded” and “The Distant Guns”, were inspired by his hospital service in Arc-en-Barrois. Artists Rifles, a CD audiobook published in 2004, includes a reading of For the Fallen by Binyon himself. The recording itself is undated and appeared on a 78 rpm disc issued in Japan. Other Great War poets heard on the CD include Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, David Jones and Edgell Rickword. Post-war life After the war, he returned to the British Museum and wrote numerous books on art; in particular on William Blake, Persian art, and Japanese art. His work on ancient Japanese and Chinese cultures offered strongly contextualised examples that inspired, among others, the poets Ezra Pound and W. B. Yeats. His work on Blake and his followers kept alive the then nearly-forgotten memory of the work of Samuel Palmer. Binyon’s duality of interests continued the traditional interest of British visionary Romanticism in the rich strangeness of Mediterranean and Oriental cultures. In 1931, his two volume Collected Poems appeared. In 1932, Binyon rose to be the Keeper of the Prints and Drawings Department, yet in 1933 he retired from the British Museum. He went to live in the country at Westridge Green, near Streatley (where his daughters also came to live during the Second World War). He continued writing poetry. In 1933–1934, Binyon was appointed Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. He delivered a series of lectures on The Spirit of Man in Asian Art, which were published in 1935. Binyon continued his academic work: in May 1939 he gave the prestigious Romanes Lecture in Oxford on Art and Freedom, and in 1940 he was appointed the Byron Professor of English Literature at University of Athens. He worked there until forced to leave, narrowly escaping the German invasion of Greece in April 1941 . He was succeeded by Lord Dunsany, who held the chair in 1940-1941. Binyon had been friends with Ezra Pound since around 1909, and in the 1930s the two became especially close; Pound affectionately called him “BinBin”, and assisted Binyon with his translation of Dante. Another protégé was Arthur Waley, whom Binyon employed at the British Museum. Between 1933 and 1943, Binyon published his acclaimed translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in an English version of terza rima, made with some editorial assistance by Ezra Pound. Its readership was dramatically increased when Paolo Milano selected it for the “The Portable Dante” in Viking’s Portable Library series. Binyon significantly revised his translation of all three parts for the project, and the volume went through three major editions and eight printings (while other volumes in the same series went out of print) before being replaced by the Mark Musa translation in 1981. At his death he was also working on a major three-part Arthurian trilogy, the first part of which was published after his death as The Madness of Merlin (1947). He died in Dunedin Nursing Home, Bath Road, Reading, on 10 March 1943 after an operation. A funeral service was held at Trinity College Chapel, Oxford, on 13 March 1943. There is a slate memorial in St. Mary’s Church, Aldworth, where Binyon’s ashes were scattered. On 11 November 1985, Binyon was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The inscription on the stone quotes a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Daughters His three daughters Helen, Margaret and Nicolete became artists. Helen Binyon (1904–1979) studied with Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious, illustrating many books for the Oxford University Press, and was also a marionettist. She later taught puppetry and published Puppetry Today (1966) and Professional Puppetry in England (1973). Margaret Binyon wrote children’s books, which were illustrated by Helen. Nicolete, as Nicolete Gray, was a distinguished calligrapher and art scholar. Bibliography of key works Poems and verse * Lyric Poems (1894) * Porphyrion and other Poems (1898) * Odes (1901) * Death of Adam and Other Poems (1904) * London Visions (1908) * England and Other Poems (1909) * “For The Fallen”, The Times, 21 September 1914 * Winnowing Fan (1914) * The Anvil (1916) * The Cause (1917) * The New World: Poems (1918) * The Idols (1928) * Collected Poems Vol 1: London Visions, Narrative Poems, Translations. (1931) * Collected Poems Vol 2: Lyrical Poems. (1931) * The North Star and Other Poems (1941) * The Burning of the Leaves and Other Poems (1944) * The Madness of Merlin (1947) In 1915 Cyril Rootham set “For the Fallen” for chorus and orchestra, first performed in 1919 by the Cambridge University Musical Society conducted by the composer. Edward Elgar set to music three of Binyon’s poems ("The Fourth of August", “To Women”, and “For the Fallen”, published within the collection “The Winnowing Fan”) as The Spirit of England, Op. 80, for tenor or soprano solo, chorus and orchestra (1917). English arts and myth * Dutch Etchers of the Seventeenth Century (1895), Binyon’s first book on painting * John Crone and John Sell Cotman (1897) * William Blake: Being all his Woodcuts Photographically Reproduced in Facsimile (1902) * English Poetry in its relation to painting and the other arts (1918) * Drawings and Engravings of William Blake (1922) * Arthur: A Tragedy (1923) * The Followers of William Blake (1925) * The Engraved Designs of William Blake (1926) * Landscape in English Art and Poetry (1931) * English Watercolours (1933) * Gerard Hopkins and his influence (1939) * Art and freedom. (The Romanes lecture, delivered 25 May 1939). Oxford: The Clarendon press, (1939) Japanese and Persian arts * Painting in the Far East (1908) * Japanese Art (1909) * Flight of the Dragon (1911) * The Court Painters of the Grand Moguls (1921) * Japanese Colour Prints (1923) * The Poems of Nizami (1928) (Translation) * Persian Miniature Painting (1933) * The Spirit of Man in Asian Art (1936) Autobiography * For Dauntless France (1918) (War memoir) Biography * Botticelli (1913) * Akbar (1932) Stage plays * Brief Candles A verse-drama about the decision of Richard III to dispatch his two nephews * “Paris and Oenone”, 1906 * Godstow Nunnery: Play * Boadicea; A Play in eight Scenes * Attila: a Tragedy in Four Acts * Ayuli: a Play in three Acts and an Epilogue * Sophro the Wise: a Play for Children * (Most of the above were written for John Masefield’s theatre). * Charles Villiers Stanford wrote incidental music for Attila in 1907. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurence_Binyon

Edward Lear (12 or 13 May 1812 – 29 January 1888) was an English artist, illustrator, author and poet, and is known now mostly for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose and especially his limericks, a form he popularised. His principal areas of work as an artist were threefold: as a draughtsman employed to illustrate birds and animals; making coloured drawings during his journeys, which he reworked later, sometimes as plates for his travel books; as a (minor) illustrator of Alfred Tennyson's poems. As an author, he is known principally for his popular nonsense works, which use real and invented English words. Early years Lear was born into a middle-class family in the village of Holloway near London, the penultimate of twenty-one children (and youngest to survive) of Ann Clark Skerrett and Jeremiah Lear. He was raised by his eldest sister, also named Ann, 21 years his senior. Owing to the family's limited finances, Lear and his sister were required to leave the family home and live together when he was aged four. Ann doted on Edward and continued to act as a mother for him until her death, when he was almost 50 years of age. Lear suffered from lifelong health afflictions. From the age of six he suffered frequent grand mal epileptic seizures, and bronchitis, asthma, and during later life, partial blindness. Lear experienced his first seizure at a fair near Highgate with his father. The event scared and embarrassed him. Lear felt lifelong guilt and shame for his epileptic condition. His adult diaries indicate that he always sensed the onset of a seizure in time to remove himself from public view. When Lear was about seven years old he began to show signs of depression, possibly due to the instability of his childhood. He suffered from periods of severe melancholia which he referred to as "the Morbids.” Artist Lear was already drawing "for bread and cheese" by the time he was aged 16 and soon developed into a serious "ornithological draughtsman" employed by the Zoological Society and then from 1832 to 1836 by the Earl of Derby, who kept a private menagerie at his estate Knowsley Hall. Lear's first publication, published when he was 19 years old, was Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots in 1830. His paintings were well received and he was compared favourably with the naturalist John James Audubon. Among other travels, he visited Greece and Egypt during 1848–49, and toured India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) during 1873–75. While travelling he produced large quantities of coloured wash drawings in a distinctive style, which he converted later in his studio into oil and watercolour paintings, as well as prints for his books. His landscape style often shows views with strong sunlight, with intense contrasts of colour. Throughout his life he continued to paint seriously. He had a lifelong ambition to illustrate Tennyson's poems; near the end of his life a volume with a small number of illustrations was published. Relationships Lear's most fervent and painful friendship involved Franklin Lushington. He met the young barrister in Malta in 1849 and then toured southern Greece with him. Lear developed an undoubtedly homosexual passion for him that Lushington did not reciprocate. Although they remained friends for almost forty years, until Lear's death, the disparity of their feelings for one another constantly tormented Lear. Indeed, none of Lear's attempts at male companionship were successful; the very intensity of Lear's affections seemingly doomed the relationships. The closest he came to marriage with a woman was two proposals, both to the same person 46 years his junior, which were not accepted. For companions he relied instead on friends and correspondents, and especially, during later life, on his Albanian Souliote chef, Giorgis, a faithful friend and, as Lear complained, a thoroughly unsatisfactory chef. Another trusted companion in Sanremo was his cat, Foss, which died in 1886 and was buried with some ceremony in a garden at Villa Tennyson. San Remo and death Lear travelled widely throughout his life and eventually settled in Sanremo, on his beloved Mediterranean coast, in the 1870s, at a villa he named "Villa Tennyson". Lear was known to introduce himself with a long pseudonym: "Mr Abebika kratoponoko Prizzikalo Kattefello Ablegorabalus Ableborinto phashyph" or "Chakonoton the Cozovex Dossi Fossi Sini Tomentilla Coronilla Polentilla Battledore & Shuttlecock Derry down Derry Dumps" which he based on Aldiborontiphoskyphorniostikos. After a long decline in his health, Lear died at his villa in 1888, of the heart disease from which he had suffered since at least 1870. Lear's funeral was said to be a sad, lonely affair by the wife of Dr. Hassall, Lear's physician, none of Lear's many lifelong friends being able to attend. Lear is buried in the Cemetery Foce in San Remo. On his headstone are inscribed these lines about Mount Tomohrit (in Albania) from Tennyson's poem To E.L. [Edward Lear], On His Travels in Greece: all things fair. With such a pencil, such a pen. You shadow forth to distant men, I read and felt that I was there. The centenary of his death was marked in Britain with a set of Royal Mail stamps in 1988 and an exhibition at the Royal Academy. Lear's birthplace area is now marked with a plaque at Bowman's Mews, Islington, in London, and his bicentenary during 2012 was celebrated with a variety of events, exhibitions and lectures in venues across the world including an International Owl and Pussycat Day on his birthday. References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lear

Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson, CBE (17 February 1864– 5 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the district around Binalong, New South Wales, where he spent much of his childhood. Paterson’s more notable poems include “Waltzing Matilda”, “The Man from Snowy River” and “Clancy of the Overflow”.

I am a believing and practicing Christian. I study God's word daily. I write Christian poetry but I also write on other topics. My poems are very simple. I don't use fancy or big words so this may be disappointing to some. I love the old Classic Poets like Sara Teasdale, Robert Louis Stevenson, and a whole host of others. I love all kinds of music from hard rock to classical. I'd like to share a few quotes, sorry I do not have all the names of the authors; Never allow someone to be your priority while allowing yourself to be their option” “A woman often thinks she regrets the lover, when she only regrets the love” By Francois de la Rochefoucauld “One of the hardest things in life is watching the person you love, love someone else.” “The one that seems to love the least, has the most control, in a relationship” “I love walking in the rain, 'cause then no-one knows I'm crying.” “Until this moment, I never understood how hard it was to lose something you never had.” “Being hurt by someone you truly care about leaves a hole in you heart that only love can fill.” “The love that lasts the longest is the love that is never returned.” "I dropped a tear in the ocean, and when you find it, that is when I will stop loving you. A few Quotes from Me, Debra A man should always, say what he means, and mean what he says, because, this is his signature. The more people you have in your life, the more problems, there will be to endure. Smart is a woman who guards her heart. Foolish is a woman, who lets a man, tare her heart apart. © Debra

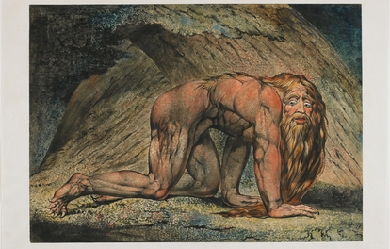

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”. His visual artistry has led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”. Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God”, or “Human existence itself”.

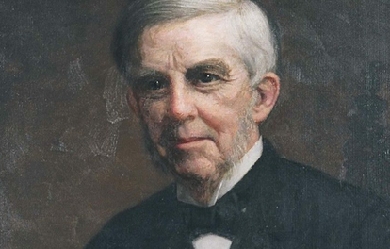

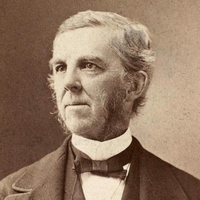

Oliver Wendell Holmes (August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He was also an important medical reformer. In addition to his work as an author and poet, Holmes also served as a physician, professor, lecturer, inventor, and, although he never practiced it, he received formal training in law.

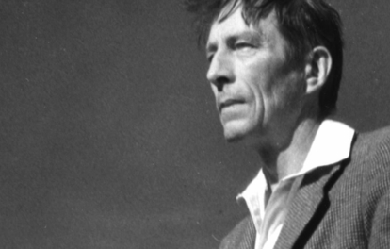

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer who wrote exclusively in English. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories and scripts for film and radio, which he often performed himself. His public readings, particularly in America, won him great acclaim; his sonorous voice with a subtle Welsh lilt became almost as famous as his works. His best-known works include the “play for voices” Under Milk Wood and the celebrated villanelle for his dying father, “Do not go gentle into that good night”. Appreciative critics have also noted the craftsmanship and compression of poems such as “In my Craft or Sullen Art”, and the rhapsodic lyricism in “And death shall have no dominion” and “Fern Hill”.

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

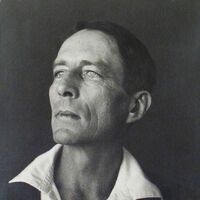

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and epic form, but he is also known for his shorter verse and is considered an icon of the environmental movement. Influential and highly regarded in some circles, despite or because of his philosophy of "inhumanism," Jeffers believed that transcending conflict required human concerns to be de-emphasized in favor of the boundless whole. This led him to oppose U.S. participation in World War II, a stand that was controversial at the time. Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), the son of a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, Reverend Dr. William Hamilton Jeffers, and Annie Robinson Tuttle. His brother was Hamilton Jeffers, who became a well-known astronomer, working at Lick Observatory. His family was supportive of his interest in poetry. He traveled through Europe during his youth and attended school in Switzerland. He was a child prodigy, interested in classics and Greek and Latin language and literature. At sixteen he entered Occidental College. At school, he was an avid outdoorsman, and active in the school's literary societies. After he graduated from Occidental, Jeffers went to the University of Southern California to study at first literature, and then medicine. He met Una Call Kuster in 1906; she was three years older than he was, a graduate student, and the wife of a Los Angeles attorney. In 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he abandoned after less than one year, at which time he returned to Los Angeles. Sometime before this, he and Una had begun an affair that became a scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times in 1912. After Una spent some time in Europe to quiet things down, the two were married in 1913, and moved to Carmel, California, where Jeffers constructed Tor House and Hawk Tower. The couple had a daughter who died a day after birth in 1914, and then twin sons (Donnan and Garth) in 1916. Una died of cancer in 1950. Jeffers died in 1962; an obituary can be found in the New York Times, January 22, 1962. Poetic career In the 1920s and 1930s, at the height of his popularity, Jeffers was famous for being a tough outdoorsman, living in relative solitude and writing of the difficulty and beauty of the wild. He spent most of his life in Carmel, California, in a granite house that he had built himself called "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Tor is a term for a craggy outcrop or lookout. Before Jeffers and Una purchased the land where Tor House would be built, they rented two cottages in Carmel, and enjoyed many afternoon walks and picnics at the "tors" near the site that would become Tor House. To build the first part of Tor House, a small, two story cottage, Jeffers hired a local builder, Michael Murphy. He worked with Murphy, and in this short, informal apprenticeship, he learned the art of stonemasonry. He continued adding on to Tor House throughout his life, writing in the mornings and working on the house in the afternoon. Many of his poems reflect the influence of stone and building on his life. He later built a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. While he had not visited Ireland at this point in his life, it is possible that Hawk Tower is based on Francis Joseph Bigger's 'Castle Séan' at Ardglass, County Down, which had also in turn influenced Yeats' poets tower, Thoor Ballylee. Construction on Tor House continued into the late 1950s and early 1960s, and was completed by his eldest son. The completed residence was used as a family home until his descendants decided to turn it over to the Tor House Foundation, formed by Ansel Adams, for historic preservation. The romantic Gothic tower was named after a hawk that appeared while Jeffers was working on the structure, and which disappeared the day it was completed. The tower was a gift for his wife Una, who had a fascination for Irish literature and stone towers. In Una's special room on the second floor were kept many of her favorite items, photographs of Jeffers taken by the artist Weston, plants and dried flowers from Shelley's grave, and a rosewood melodeon which she loved to play. The tower also included a secret interior staircase – a source of great fun for his young sons. During this time, Jeffers published volumes of long narrative blank verse that shook up the national literary scene. These poems, including Tamar and Roan Stallion, introduced Jeffers as a master of the epic form, reminiscent of ancient Greek poets. These poems were full of controversial subject matter such as incest, murder and parricide. Jeffers' short verse includes "Hurt Hawks," "The Purse-Seine" and "Shine, Perishing Republic." His intense relationship with the physical world is described in often brutal and apocalyptic verse, and demonstrates a preference for the natural world over what he sees as the negative influence of civilization. Jeffers did not accept the idea that meter is a fundamental part of poetry, and, like Marianne Moore, claimed his verse was not composed in meter, but "rolling stresses." He believed meter was imposed on poetry by man and not a fundamental part of its nature. nitially, Tamar and Other Poems received no acclaim, but when East Coast reviewers discovered the work and began to compare Jeffers to Greek tragedians, Boni & Liveright reissued an expanded edition as Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925). In these works, Jeffers began to articulate themes that contributed to what he later identified as Inhumanism. Mankind was too self-centered, he complained, and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." Jeffers's longest and most ambitious narrative, The Women at Point Sur (1927), startled many of his readers, heavily loaded as it was with Nietzschean philosophy. The balance of the 1920s and the early 1930s were especially productive for Jeffers, and his reputation was secure. In 1934, he made the acquaintance of the philosopher J Krishnamurti and was struck by the force of Krishnamurti's person. He wrote a poem entitled "Credo" which many feel refers to Krishnamurti. In Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Dear Judas and Other Poems (1929), Descent to the Dead, Poems Written in Ireland and Great Britain (1931), Thurso's Landing (1932), and Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Jeffers continued to explore the questions of how human beings could find their proper relationship (free of human egocentrism) with the divinity of the beauty of things. These poems, set in the Big Sur region (except Dear Judas and Descent to the Dead), enabled Jeffers to pursue his belief that the natural splendor of the area demanded tragedy: the greater the beauty, the greater the demand. As Euripides had, Jeffers began to focus more on his own characters' psychologies and on social realities than on the mythic. The human dilemmas of Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Medea fascinated him. Many books followed Jeffers' initial success with the epic form, including an adaptation of Euripides' Medea, which became a hit Broadway play starring Dame Judith Anderson. D. H. Lawrence, Edgar Lee Masters, Benjamin De Casseres, and George Sterling were close friends of Jeffers, Sterling having the longest and most intimate relationship with him. While living in Carmel, Jeffers became the focal point for a small but devoted group of admirers. At the peak of his fame, he was one of the few poets to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. He was also asked to read at the Library of Congress, and was posthumously put on a U.S. postage stamp. Part of the decline of Jeffers' popularity was due to his staunch opposition to the United States' entering World War II. In fact, his book The Double Axe and Other Poems (1948), a volume of poems that was largely critical of U.S. policy, came with an extremely unconventional note from Random House that the views expressed by Jeffers were not those of the publishing company. Soon after, his work was received negatively by several influential literary critics. Several particularly scathing pieces were penned by Yvor Winters, as well as by Kenneth Rexroth, who had been very positive in his earlier commentary on Jeffers' work. Jeffers would publish poetry intermittently during the 1950s but his poetry never again attained the same degree of popularity that it had in the 1920s and the 1930s. Inhumanism Jeffers coined the word inhumanism, the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." In the famous poem "Carmel Point," Jeffers called on humans to "uncenter" themselves. In "The Double Axe," Jeffers explicitly described inhumanism as "a shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence. ... This manner of thought and feeling is neither misanthropic nor pessimist. ... It offers a reasonable detachment as rule of conduct, instead of love, hate and envy ... it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty." In The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers,the first in-depth study of Jeffers not written by one of his circle, poet and critic J. Radcliffe Squires addresses the question of a reconciliation of the beauty of the world and potential beauty in mankind: “Jeffers has asked us to look squarely at the universe. He has told us that materialism has its message, its relevance, and its solace. These are different from the message, relevance, and solace of humanism. Humanism teaches us best why we suffer, but materialism teaches us how to suffer.” Influence His poems have been translated into many languages and published all over the world. Outside of the United States he is most popular in Japan and the Czech Republic. William Everson, Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, and Mark Jarman are just a few recent authors who have been influenced by Jeffers. Charles Bukowski remarked that Jeffers was his favorite poet. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz also took an interest in Jeffers' poetry and worked as a translator for several volumes of his poems. Jeffers also exchanged some letters with his Czech translator and popularizer, the poet Kamil Bednář. Writer Paul Mooney (1904–1939), son of American Indian authority James Mooney (1861–1921) and collaborator of travel writer Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), "was known always to carry with him (a volume of Jeffers) as a chewer might carry a pouch of tobacco ... and, like Jeffers," writes Gerry Max in Horizon Chasers, "worshipped nature ... (taking) refuge (from the encroachments of civilization) in a sort of chthonian mysticism rife with Greek dramatic elements ..." Jeffers was an inspiration and friend to western U.S. photographers of the early twentieth century, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Morley Baer. In fact, the elegant book of Baer's photographs juxtaposed with Jeffers' poetry, combines the creative talents of those two residents of the Big Sur coast. Although Jeffers has largely been marginalized in the mainstream academic community over the last thirty years, several important contemporary literary critics, including Albert Gelpi of Stanford University, and poet, critic and NEA chairman Dana Gioia, have consistently cited Jeffers as a formidable presence in modern literature. His poem "The Beaks of Eagles" was made into a song by The Beach Boys on their album Holland (1973). Two lines from Jeffers' poem "We Are Those People" are quoted toward the end of the 2008 film Visioneers. Several lines from Jeffers' poem "Wise Men in Their Bad Hours" ("Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made / Something more equal to the centuries / Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.") appear in Christopher McCandless' diary. Robinson Jeffers is mentioned in the 2004 film I Heart Huckabees by the character Albert Markovski played by Jason Schwartzman, when defending Jeffers as a nature writer against another character's claim that environmentalism is socialism. Markovski says, "Henry David Thoreau, Robinson Jeffers, the National Geographic Society...all socialists?" Further reading and research The largest collections of Jeffers' manuscripts and materials are in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and in the libraries at Occidental College, the University of California, and Yale University. A collection of his letters has been published as The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1887–1962 (1968). Other books of criticism and poetry by Jeffers are: Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years (1949), Themes in My Poems (1956), Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems (1965), The Alpine Christ and Other Poems (1974), What Odd Expedients" and Other Poems (1981), and Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers (1987). Stanford University Press recently released a five-volume collection of the complete works of Robinson Jeffers. In an article titled, "A Black Sheep Joins the Fold", written upon the release of the collection in 2001, Stanford Magazine commented that it was remarkable that, due to a number of circumstances, "there was never an authoritative, scholarly edition of California’s premier bard" until the complete works published by Stanford. Biographical studies include George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (1926); Louis Adamic, Robinson Jeffers (1929); Melba Bennett, Robinson Jeffers and the Sea (1936) and The Stone Mason of Tor House (1966); Radcliffe Squires, The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers (1956); Edith Greenan, Of Una Jeffers (1939); Mabel Dodge Luhan, Una and Robin (1976; written in 1933); Ward Ritchie, Jeffers: Some Recollections of Robinson Jeffers (1977); and James Karman, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of California (1987). Books about Jeffers's career include L. C. Powell, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and His Work (1940; repr. 1973); William Everson, Robinson Jeffers: Fragments of an Older Fury (1968); Arthur B. Coffin, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of Inhumanism (1971); Bill Hotchkiss, Jeffers: The Sivaistic Vision (1975); James Karman, ed., Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers (1990); Alex Vardamis The Critical Reputation of Robinson Jeffers (1972); and Robert Zaller, ed., Centennial Essays for Robinson Jeffers (1991). The Robinson Jeffers Newsletter, ed. Robert Brophy, is a valuable scholarly resource. In a rare recording, Jeffers can be heard reading his "The Day Is A Poem" (September 19, 1939) on Poetry Speaks – Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Narrated by Charles Osgood (Sourcebooks, Inc., c2001), Disc 1, #41; including text, with Robert Hass on Robinson Jeffers, pp. 88–95. Jeffers was also on the cover of Time – The Weekly Magazine, April 4, 1932 (pictured on p. 90. Poetry Speaks). Jeffers Studies, a journal of research on the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and related topics, is published semi-annually by the Robinson Jeffers Association. Bibliography * Flagons and Apples. Los Angeles: Grafton, 1912. * Californians. New York: Macmillan, 1916. * Tamar and Other Poems. New York: Peter G. Boyle, 1924. * Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925. * The Women at Point Sur. New York: Liveright, 1927. * Cawdor and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1928. * Dear Judas and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1929. * Thurso's Landing and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1932. * Give Your Heart to the Hawks and other Poems. New York: Random House, 1933. * Solstice and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1935. * Such Counsels You Gave To Me and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1937. * The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. New York: Random House, 1938. * Be Angry at the Sun. New York: Random House, 1941. * Medea. New York: Random House, 1946. * The Double Axe and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1948. * Hungerfield and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1954. * The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1963. * Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1965. * Stones of the Sur. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robinson_Jeffers

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674– 25 November 1748) was an English Christian minister, hymnwriter, theologian and logician. A prolific and popular hymn writer, his work was part of evangelization. He was recognized as the “Father of English Hymnody”, credited with some 750 hymns. Many of his hymns remain in use today and have been translated into numerous languages.

I love to write poems. It helps me to put down my feelings and I guess it's a way of venting. I have 2 sons, Jeff & Gary my grandson Josh & granddaughter Caitlin & my baby boy Rocky a ( Shih Tzu). I am so very pleased to say my son Gary and Jen are now husband and wife. They were married on 8/16/15. Such a beautiful Wedding and a most Wonderful Couple who Love each other very much. The best part is from this union I have 2 more grandsons Dillon and Colton, 3 beautiful granddaughters Samy (Samantha), Bella Mia and Addy (Addison) and 2 great grandsons Domy and Austin. This marriage means so very much to me. My daughter in law Jenny has raised her granddaughter Bella since she was 5 days old. She adopted her and her name is Bella Mia (2 years old). She is beautiful like her name. Together my son Gary and Jen will be adopting Bella's half sister Addy (5 years old). Jenny has been fighting to adopt Addy for more than 2 years. Addy has been awarded into the custody of Jenny and Gary. She will be flying home with Jenny on 8/28/15 from Florida to her "FOREVER HOME". In 90 days they will be allowed to adopt Addy. So both Bella and Addy are also my granddaughters. I am so very Happy. I now have a very large and loving family. I have written poems about Addy, and I want to Thank those of you who helped me pray for her to become family. Such a wonderful miracle has been witnessed. She is family now and she is beautiful. I love my daughter in law as she is a wonderful person, a fantastic Mom and a wonderful wife to my son. My son Jeffrey is my Hero. He's an upstanding guy, Honest and true. I'm so proud of him. He's also my Best Friend. God Bless. Sandi.